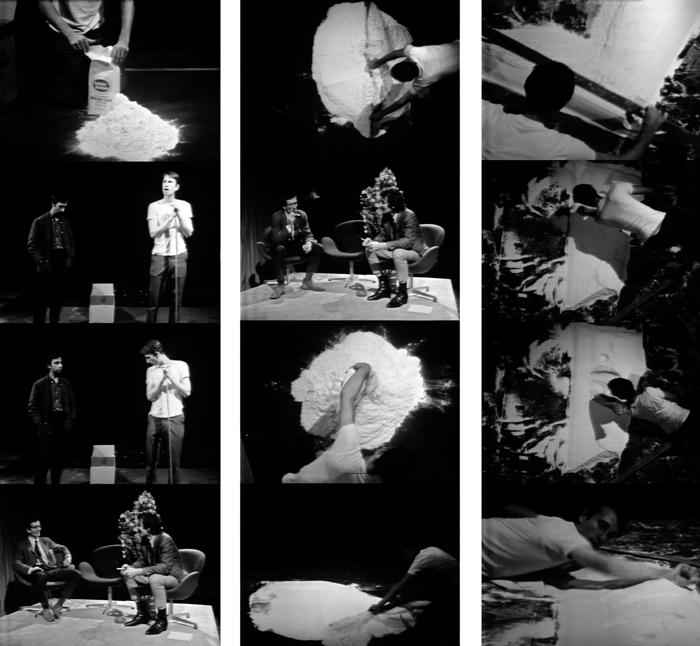

Bruce Nauman, Untitled (Flour Arrangements), made with William Allan and Peter Saul for the Experimental Television Project, KQED, Channel 9, 1967. Video, black-and-white, sound; 23 min., 59 sec. University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. © 2006 Bruce Nauman/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

A Rose Has No Teeth: Bruce Nauman in the 1960s, the exhibition title chosen by curator Constance Lewallen, is a reference to Nauman’s first text piece, a stamped plaque titled A Rose Has No Teeth (Lead Tree Plaque)(1966). Nauman intended the plaque to be attached to a tree, allowing the bark to overtake it, covering the Wittgenstein quote and eventually the entire piece from view. This gesture speaks to the ephemeral ties that run throughout the exhibition. Various mediums—drawing, photography, sound installation and sculpture—spill out across multiple floors of the Berkeley Art Museum. To heighten the sensory experience further, films and videos butt up against everything as open audio plays as a sound track over it all. Though the broad scope of the Berkeley Art Museum exhibition could initially be read as a sweeping retrospective, Lewallen has actually presented a more localized proposal, emphasizing Nauman’s Northern Californian influences during 1964-69 as influential in the development of his practice.

After graduating from UC Davis in 1966, Nauman moved to San Francisco, where his feelings of isolation were coupled with meager financial resources. Grappling with the question of what it meant to be an artist, he found resolve by going to work in his studio. Nauman produced a range of over 100 works during this challenging five-year period and many are presented in this show. Lewallen’s extensive research, outlined in the exhibition catalog, states that Nauman was encouraged by support from regional artists and cohorts like California Funk artist William T. Wiley. Nauman is quoted as saying “Wiley was the strongest influence I had. It was in being rigorous, being honest with yourself—trying to be clear—taking a moral position.”1 Lewallen states: “Wiley was inspiring, always open and receptive to unorthodox ideas, and carried no preconceptions. His work has always been a by-product of his life (the synchronicity of art and life is shared by many artists in the region), and anything and everything was potential content.”2 Wiley’s influence is evident in Nauman’s inventive use of puns and the stuff of everyday life as content for his work. In addition to Wiley, several other California Funk artists were professors at UC Davis during the time that Nauman was a student there, including Robert Arneson, Wayne Thiebaud, Roy De Forest, and Manuel Neri. Although the aesthetics of California Funk may not be recognizable in Nauman’s work, the attitudes his professors supported—an inclination toward free exploration of ideas and forms—are apparent. Given that Lewallen constructed the show around these regional influences, it is unfortunate that Wiley, and other California Funk artists, are not visually represented in the catalog or show. The movement’s commitments to experimentation and to the use of the everyday are two models that help define Nauman’s practice to this day.

A sculpture that embodies these concepts is A Cast of the Space Under My Chair (1965-1968). Nauman’s cement cast of the negative space of a chair invokes the positive form of the chair from which it was made. Nauman brings attention to a part of the chair—the underside—in which we would otherwise have no interest. In Dark (1968), Nauman again asks us to look beyond what is immediately in front of us. In this work, Nauman wrote the word “dark” in yellow permanent marker underneath a two-ton slab of steel. By directing our attention to the word beneath the un-liftable object, the non-visible, underside of the object becomes the point of interest. We cannot see the underside, but we can conceptualize it and are thus reminded of its significance to the object as a whole.

As in much of Nauman’s work, the idea transcends the object and remains accessible long after we have physically left the artwork. Nauman’s approach of stating the obvious, remaining aware and seeking out possibilities in familiar objects, transforms our understanding of them. The formality and concreteness of a sculpture disappears when the unobserved is foregrounded and given meaning. Nauman demonstrates the overlooked, the in-between and the unacknowledged by using that with which we are most familiar. These early works resonate within the history of sculpture, revealing unexpected potential in objects that were once deemed too ordinary for attention.

A series of Nauman’s films from 1965-1966, made in collaboration with William Allan, revisit an interest in the ephemeral and Nauman’s ability to unhinge our thoughts from the physicality of objects. The unpretentious and grainy appearance of the films contrasts noticeably with the high definition look of media today. One film documents the two men exploring a mutual interest in recording “non-art” activities such as fishing. Span (1966), follows them as they rig a black tarp to span across a river and conveys the importance of process in any final outcome. The film is defined by actions of lifting lumber from the top of a VW Beetle, walking to the site, hammering, and sloshing through the water. We see the object being built from beginning to end with little illusion. After the tarp is constructed, it blows gently in the wind, reflecting the moving water below it, and blends into its surroundings. As the tarp seemingly disappears into the environment, we are left to contemplate the core of the piece—the process of the object being built.

In the video untitled (Flour Arrangements) (1967), William Allan and Peter Saul act as TV hosts on a mock television show, smoking while commenting on Nauman’s performance. We watch from above as Nauman drags a 2 x 4 across a 50-pound pile of flour, shaping it into various sculptural patterns on the floor. Meanwhile, the hosts comment on Nauman’s movements as if they are watching an athlete performing in a sporting event. The ever-changing sculptures are each erased by the next, ending with Nauman signing his name in the flour. After the video ended I imagined how his name would also be erased from view—a reminder that art and life are both impermanent circumstances. Nauman’s use of self-deprecating humor, his invocation of failure and vulnerability bring to mind the physical comedy of Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin and Lucille Ball. In a like manner, Nauman places himself in existential predicaments utilizing humor as a way to engage the audience. As a vehicle for laughter and observation, he positions himself as the artist delivering the joke while also existing as the punch line.

Bruce Nauman, Failing to Levitate in the Studio, 1966. Black-and-white photograph; 20 x 24 inches. Collection of the Artist. © 2006 Bruce Nauman/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

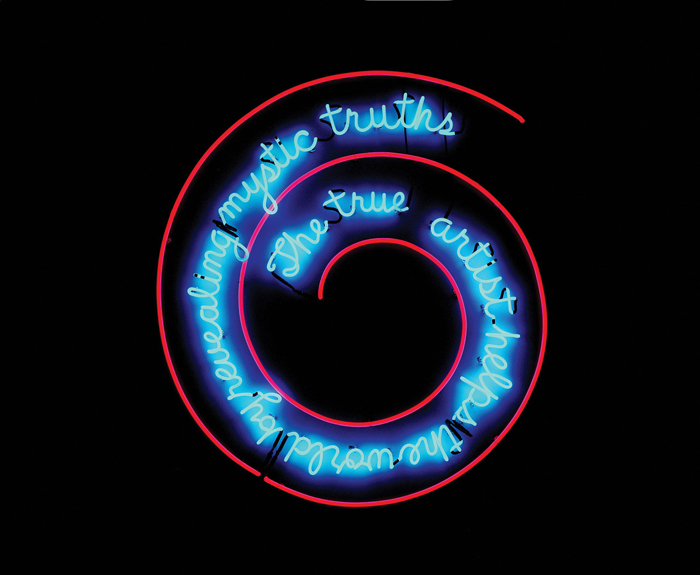

The True Artist Helps the World By Revealing Mystic Truths (1967), a neon sculpture that writes the text of the title in glowing blue cursive, and Failure to Levitate in the Studio (1966), a black and white double-exposure of Nauman’s body slumped on the floor between two chairs, present opposing questions. The works ask: Is the artist meant to transcend and suspend disbeliefs and reveal mystic truths? Or is the artist’s function practice and process and the possibilities of failure? Through the act of making these diverse works, he tells us that the answer is both and, perhaps, neither—given how the humor pulls the rug out from under such grandiose claims.

Accepting contradiction and exploration as a methodology, Nauman invents experiments that produce an open questioning, never building a defense before work is made. Today, I rarely experience art that admits vulnerability by acknowledging failure, the unknown and its own process. Nauman’s approach values investigative thought and his process reminds us as artists to find the space to explore ideas beyond premeditation and against external pressures. He embraces the mental freedom that is integral to any thoughtful art practice.

Bruce Nauman, The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Window or Wall Sign), 1967. Neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frame; 59 x 55 x 2 inches. Artist’s proof. Collection of the Artist. Courtesy of Sperone Westwater, New York. © 2006 Bruce Nauman/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Nauman’s studio works from 1967-68 continue to reflect his interest in the structure of his own practice. Engaging with the premise that whatever an artist does in her or his studio qualifies as art,3he uses his body by rigorously pacing, walking, stamping, spinning and running around in laborious video performances. In Playing A Note on the Violin While I Walk Around the Studio (1967-68), Nauman, as a magnified and unapologetic figure, repeatedly plays one note on a violin and paces around his studio. Bouncing in the Corner (1968) is another investigation in rhythm and physical exertion. The video is framed to exclude Nauman’s head as he literally bounces in the corner of his studio for one hour. The repetitious rhythm of his bouncing becomes a test of endurance for both Nauman and the viewer. Since we do not see his facial expressions, we perceive him merely as a constant element in the corner of his studio. These videos exhaust both the artist and his audience. Eventually we lose interest in his repetitious actions and focus on other subjects in his studio within the camera’s frame. Our attention switches from Nauman’s body to our viewing position in relation to the architecture of his studio, never settling on one thing concretely.

Nauman currently lives on a ranch in New Mexico, acres from the art world. He perseveres in his early principles by investigating concepts that he explored in the 1960s. In Setting a Good Corner, a video from 2000, he documented the “non-art” activity of digging a hole and setting a corner to his fence. In Mapping the Studio I (Fat Chance John Cage) (2002), he used an infrared camera to record his studio at night after he had gone to sleep. Capturing sounds of a screen door closing and footage of a cat and mouse chasing through scraps of past projects, Nauman continues to question the artist’s role, revealing the double life of his studio as a dynamic space even in his absence. Most recently Nauman constructed a piece for Skulptor Projekte Munster 07 that he designed thirty years ago, titled Square Depression (2007). The city-block-sized concrete depression, built six feet below ground level, invites viewers to descend to the center of what is referred to as a “negative stage.”4 Similar to Nauman’s early negative space works, the impression of an object in concrete summons its reverse, the form from which it was made.

Experiencing over one hundred Nauman works was overwhelming, considering that just one of his pieces alone is enough to make my head hurt. The poetics associated with acknowledging something bigger than oneself, as well as ideas of existence and erasure, progressed meaningfully throughout the Berkeley exhibition. Nauman’s investigations ultimately extend beyond materiality; he asks us to question our common perceptions and advances our thoughts into a space that is not moored to objects themselves. He tells us as artists to get to work, to be clear and to not take ourselves too seriously.

Wendy Mason is a Los Angeles-based artist and co-founder of Slab projects, an artist-run exhibition concept based on the cement circle in her backyard.