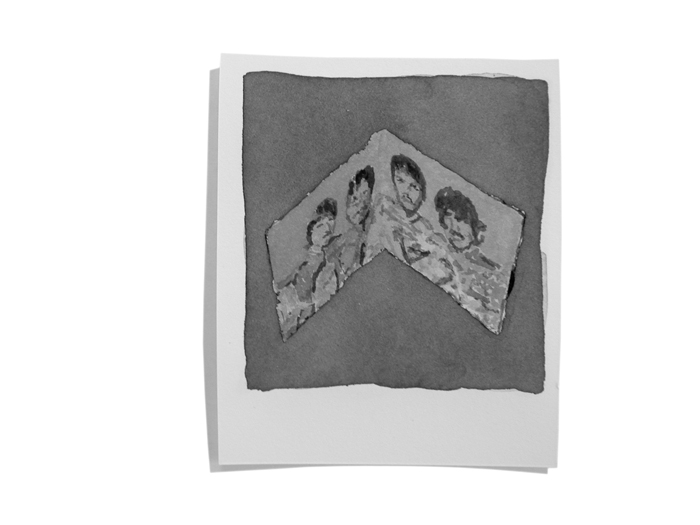

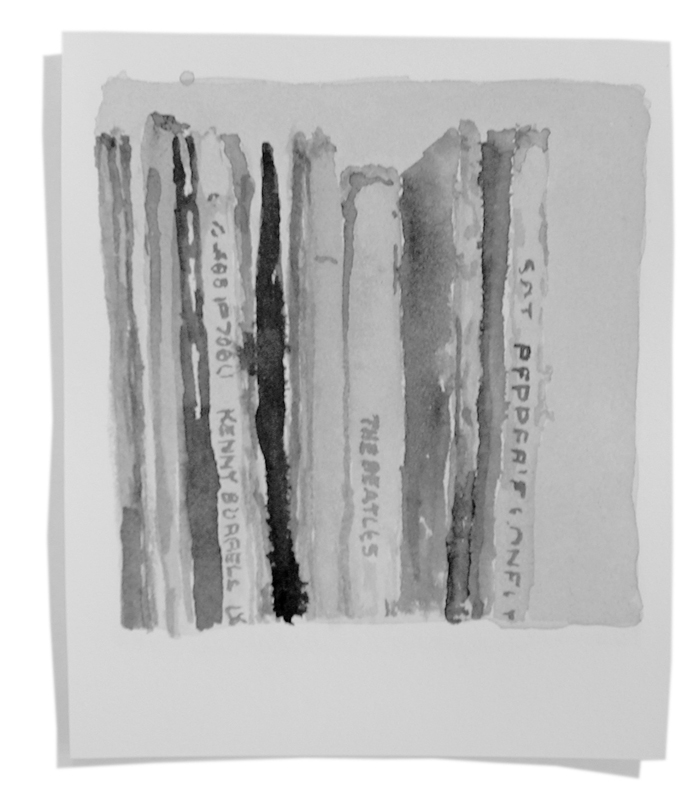

Dave Muller, Interior gatefold, 2004

5. War and media studies (continued)

A “father” to the ‘60s generation, Walter Benjamin is among the first to attempt a unified theorization of the impact of media—that is, the information technologies of mechanical reproduction—upon social consciousness. Beginning with the invention of movable type and the printing press, the traditional modes of disseminating knowledge from one person to another begin to give way to a generalized broadcasting. For Benjamin, this is emphatically a matter of form. The “culture of literacy,” as it comes to be known in the ‘60s, addresses its audience in a very different way than the “culture of orality” that preceded it. The very same message, split between these two modes, will carry radically divergent implications. The culture of literacy gives birth to the modern individual, suggests Benjamin; it actively produces that subjectivity at the receiving end of the text. “Knowledge,” that which was formerly passed from one person to another, becomes “information,” a systematic abstraction prepared for consumption by a faceless, generic mass. This is the paradoxical source of modern individuality, according to Benjamin; it is from the outset a value that can only be measured statistically, as a demographic. As a destination for messages it is akin to a vanishing point.

At the point of production, the modern author, represented mainly by the modern novelist, becomes similarly discon- nected. “The novelist has secluded himself,” writes Benjamin. “The birthplace of the novel is the individual in his isolation, the individual who can no longer speak of his concerns in exemplary fashion, who himself lacks counsel and can give none.”1Whereas orality collapsed the phases of narrative production and reception into a single instant of social presence and participation, the inception of literacy pulls them apart once and for all time. The producer retreats into his solitude and the receivers, in turn, dissolve into their multitude. Texts not only pass between these two contexts of production and reception, the one and the many, but they actively produce them as such. As fundamental abstractions, they are endowed with much the same sort of autonomy that characterize modernist artworks: the capacity to negate, deny or simply forget their own particular origins. In this way, authorship can be reduced to the secluded and hyper-individuated self; but this self is entirely a product of the generic mass at the receiving end of the text, and vice versa. These parties produce each other across the line of their commu- nication, this line which simultaneously connects and divides them.

Thus it is not only war, but also the modern media, that deplete our experiential capacities to both remember and tell stories. War and media are already being considered parallel conditions in Benjamin’s writings, delivering analogous sorts of “shocks” to the system. According to him, shock throws the delicate apparatus of human sense- perception into reverse. Initially media serve to augment the acuity of sense-perception to worldly phenomena; however, one always runs the risk of over-stimulation, and subsequent numbing. At the extreme, nothing more comes in, and the once-finely tuned sensory apparatus is reduced to a single, blunt function: that of shock absorber. In this way, the neurasthenic dandy, glutted on spectacle, suffers a very similar set of symptoms as the shell-shocked soldier: both have been over-stimulated into submission. The latter acquires his condition as a consequence of serving the state whereas the former is only in it for himself, but both wind up in the same place of dismal solitude, literally excommunicated and silenced.

Dave Muller, Exterior, 2004

6. Enter everyman

In between its first and penultimate songs, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band has effectively come and gone. As transitional and compensatory figures preparing the way to a new phase in The Beatles’ evolution — post-touring, post-performance, post-live — they are designed to self- destruct once they have made their (or The Beatles’) case. But Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band does not close with the celebratory conclusion of “Good Morning, Good Morning”; one last song is added to the mix. “A Day in the Life” appears at first as an anomaly or afterthought, but should one choose to approach it instead as the whole crux of Sgt. Pepper’s “argument,” then the song will act as a virus, retroactively implanting every prior song with the express directive to introduce and cede way to this one.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is entrusted with the apology that The Beatles must deliver to their public on the eve of their break-up, but they must also explain. This they do in a roundabout way, by celebrating the simple pleasures of rootedness, community and home. But home, for The Beatles, is precisely where their fans are not. As a marching band that once traveled great distances to appear before you, in your very own town, this decision to remain put cannot be taken lightly. The band has renounced the road that brings it toward its audiences, and in so doing it also becomes much more like those audiences. And this is effectively the voice of “A Day in the Life:” not soldier or itinerant rocker, but now truly the “everyman.”

A tone of utter banality is established within the very first line of the song: “I read the news today oh boy….” Every song prior to this one has concerned active steps, taken in work or play, to reconnect with one’s original community, but the protagonist of “A Day in the Life” is perfectly content to commune via the newspaper, and a few lines later, via film. These forms must be understood as sorry substitutes for actual experience — the sense of belonging somewhere and participating in its affairs. A McLuhanesque “coolness” prevails here, and again it is perfectly encapsulated within that first line, by the newspaper reader’s ambivalent reaction: “oh boy.”

What this “communicates” is not much, precisely; a vague sense of the overwhelming nature of the problem, but not much more. From the outset, rather, we are witnessing the formation of a media feedback loop. In the ever- quickening volley of action and reaction, the intermediate moment of reflection — what Aby Warburg termed denkraum, or “thinking room”— is gradually eclipsed. In this way, the reader’s response is instantly appended to the action, as is the reader him/herself, incidentally. Taking this new context into account, “oh boy” is actually the “correct” answer; it is evidence of the reader’s internaliza- tion and regurgitation of the language of

media — information.

The decline of meaningful dialogue and its replacement by a bland, delocalized palaver, a kind of zero-degree, white- noise sociality, is a condition noted throughout the Sgt. Pepper album. There remains a glaring void, an almost palpable silence, at the core of public discourse and debate, and it is this, in place of communicable experience, that will get passed down through the ages. As a member of the next generation — this is evident in the use of such terms as “blew his mind” or “turn you on,” for instance — the protagonist of “A Day in the Life” in effect becomes the ultimate repository of a half-century’s worth of silence and sublimation.

This “switched-on” verbiage, with its barely veiled psychonaut-style appreciation of the problems of perception, is an indication of the generational turnover that has taken place, but there are more pointed ones. The lyric pieced together from found media sources is itself evidence of a newly decentered sensibility. This is a form of montage, but one that has invaded the subject’s inner being, to become almost a psychological state. If, as the critic Dan Curtis suggests, Sgt. Pepper is all about the “assimilation of outside to inside,”2then “A Day in the Life” marks its culminating moment. In the Eastern philosophies that are beginning to impact The Beatles’ thinking, this “assimilation” is a prerequisite to enlightenment, but it is clearly another order of consciousness that we are meant to consider here. The protagonist of “A Day in the Life” is, frankly, an emotional mess. At the sight of what is likely an atrocity photograph, he bursts out laughing. The tragic fate of “a lucky man who made the grade” to die, stupidly, in a car crash because “[h]e didn’t notice that the lights had changed,” might prompt a wry sort of bemusement, but laughter is clearly beyond the pale.

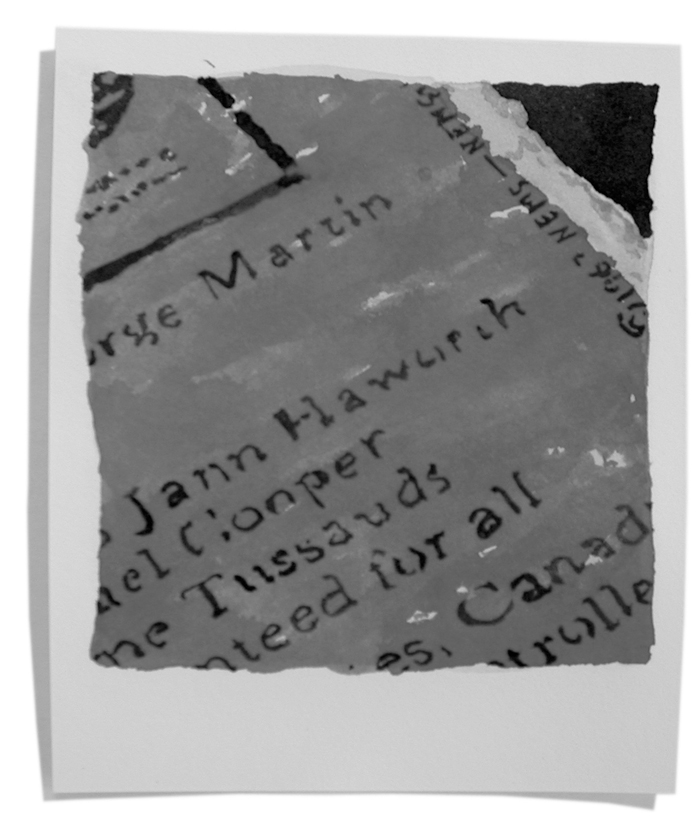

Dave Muller, Martin, Hawoorth, Cooper ,Tussand, for all, 2004

The story is taken from the Daily Mail, January 17, 1967, and concerns the death of Tara Browne, a young and very wealthy friend of The Beatles, who drove his car at high speed through a red light in South Kensington, smashing into a van. At the time, there were allegations of psychedelic drug use, and this may be the source of the insistent line that intrudes further down: “I’d love to turn you on.” John Lennon, who was responsible for writing the song’s first and last sections, was purportedly shaken by the news of this outwardly successful man’s death, but even more disturbing was the reaction of the crowd that gathered at the scene. The protagonist of “A Day in the Life” seems to be acutely aware of this crowd, and measures his own reaction to the story against theirs. “Although the news was rather sad,” he sings, “Well I just had to laugh.” “A crowd of people stood and stared,” he goes on to report, and his vaguely bitter tone again marks a measured distance from them.

The next part of the song is more perplexing, though only to us, the listeners; the singer, for his part, is characteristi- cally unreflexive. “I saw a film today oh boy / The English Army had just won the war,” he states, and this time it is the crowd that “turned away,” whereas he “just had to look / Having read the book.” By the time we get to that last line, it is clear we are dealing with a dramatization, as opposed to documentary or newsreel footage, of the war. And yet at the outset, this is not at all apparent, nor can it be, because it is in the nature of media spectacle to prompt not only inappropriate emotional responses, but also a warped sense of historical continuity. This could simply be Lennon writing about his performance in the Richard Lester film How I Won the War, which had wrapped some months earlier. Perhaps he is measuring his personal stake in the film against an anticipated critical rejection; but it is almost irrelevant what the “true” or “inside” story might be, because what we are left with is a construct of multiple voices, not one.

“A Day in the Life” is written, like so many of the best Beatles songs, by the team of John Lennon and Paul McCartney. McCartney supplies the middle-section — “Woke up, fell out of bed, / Dragged a comb across my head…”— while Lennon enfolds it in the sections on mediation. The result of these two perspectives is an account of life as a series of alternations between the so- called “Real” and a mediated “Imaginary.” In the final section, having caught the bus to wherever it is that he is going in such a rush, the song’s protagonist recalls another newspaper story. It is from the very same edition of the Daily Mail, and reports on the shoddy state of the roads in Blackburn, Lancashire. As in a dream, these disparate references all compute on a syntactical level: we are driven along by a relentless beat and a series of poetic analogies that link together the unlikeliest things. As one crowd gathers and another disperses, we have drifted between an atrocity photograph and a film about the war; we are on the bus and then we are under its wheels, observing the road. This movement conforms to a certain dream logic, but the oddest and most dream-like connection of all, the one that effectively closes the song, is also one that the newspaper makes for us. It is one of those useless factoids that somehow still manage to provoke the public’s imagination: having counted the number of holes in the road, “[n]ow they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall.”

This pseudo-revelation is followed, once last time, by the line: “I’d love to turn you on.” This could be construed as a way out of the pointless banality of what precedes it — the counting of holes in the road being an instance of just the sort of bureaucratic grind that might drive one not only to drink, but hallucinogens. However, it is just as plausible that this counting is itself a kind of hallucinogenic activity, since it leads to the formation of a seemingly absurd, and hence potentially poetic, insight. The Albert Hall and a hole in the road actually do share the same substance. Both are essentially comprised of space, and space can be measured, numbered, counted, but it cannot be qualified. Being by nature undifferentiated, it cannot be touched by the distinguishing action of language.

Each time the words “I’d love to turn you on” are sung, a gap intrudes into the dense and driven substance of the song. The drums trail off as the rapid-fire syntactical chain of lyrical analogies gives way, and a space of sorts opens here too. “…McCartney hit upon the idea of filling the song’s empty space with a cacophonous orchestral crescendo. His idea was that each musician would play from his lowest to his highest note (ideally not at the same speed as his neighbor), getting louder along the way. (Producer George) Martin hired forty musicians from London orchestras, who were given props — false noses, masks, bits of a gorilla costume — to create a circus-like atmosphere. With Martin and McCartney taking turns conducting, the orchestra recorded one crescendo for the middle of the work, and another for the end.”3 As a musical directive, the crescendo forecloses any possibility of musical “expression;” this is musical Langue at the expense of Parole. Likewise, the inclusion of the carnivalesque props is obviously intended to undermine the sort of solemnity or seriousness typically associated with the classical repertoire. The “cacophony” generated by McCartney and Martin’s instructions is clownish fun, but it also suggests the breakdown of a former order of music, a former language and thereby also (pace Adorno) a former concept of sociality.

The Albert Hall is known mainly as a venue for the performance of classical music, but The Beatles played there too. As with almost every line in “A Day in the Life,” the final mention of this hallowed British institution invites multiple readings. There is the “external,” popular reading, in this instance taken straight from the pages of the local paper by a “regular Joe,” and then there is the “internal,” ultra-cryptic reading that draws on a complexly coded constellation of social, political, biographical, psy- chological and self-reflexive sources. The first reading is evident and available to all whereas the second requires research, “insider” knowledge. Each reading is incomplete in itself, however, and this holds generally true for Sgt. Pepper and “A Day in the Life” especially, as it is here that the tension of outside and inside, public and private, comes to a head. In light of The Beatles’ own personal experience, having once played the Albert Hall but now playing live no more, one can well imagine how the vision of a former public, in its overbearing enthusiasm and liveliness, can poetically cede way to a collection of holes in the road. Maybe this even constitutes, for them, a kind of poetic relief.

Inside and outside, private and public — these terms can also be placed on either side of the stage that divides the performers from their audience, and it is clear, in this instance, that the band has abandoned its previous post in the limelight in order to experience the darker end of this equation. They are not simply taking on the perspective of the audience, but the perspective of an audience that is no longer there. Like the holes that fill the Albert Hall, they become spaces within space, silences within silence: both more and less than nothing. Having built their orchestral arrangement of lowest and highest notes to a terrible crescendo, it plateaus out and fades away in an approximation of the middle. The final sustained E-Major chord leaves off with a sense of anxious expectation; Lennon had apparently asked for “a sound like the end of the world.”4

Dave Muller, Back of Paul’s Jacket, 2004

7. My picture on the cover

Inside and outside intersect in “A Day in the Life” with frightening consequences. Meaning, language, poetry, music — that is to say, communication as such — explodes into space. Space intrudes all around as the ultimate agent of entropy, leveling out every difference, all tensions. Space as the middle-ground, the in-between, seeps in like a gas to surround and consume everything. Space as the dissolution of everything, makes room for nothing: “oh boy.”

The last sound we hear is “like the end of the world,” perhaps, but it could just as well be described as “pregnant.” This emptiness will not remain empty for long is what it seems to suggest; but what, then, should follow? Should we choose to cycle right back to the start, it will again be the sound of the audience and band, as though reanimated in tandem. This is the somewhat hellish option; the more edenic one might involve turning off the record player altogether.

Pieced together from newspaper stories and quotidian experience — materials available to all — the song that closes Sgt. Pepper is one that ostensibly anyone could write. It makes the case very effectively that the best poetic analogies are also those that are closest at hand: “turn on,” or better still, just read the paper. The voice of “A Day in the Life” is almost obsequious in its attempt to connect with the everyman. In creating nothing more or less than a void, it constitutes an open call to all on the other side of the stage: step across and make your own culture.

In fact, the years that see the release of Sgt. Pepper, The Magical Mystery Tour and the so-called “White Album,” are marked by the rapid consolidation of youth culture, as those who grew up listening to The Beatles become producers in their own right. A proliferation of bands form in their wake and, even more significantly, a whole new infrastructure of fans, amateurs and enthusiasts turned entrepreneurs — organizers, promoters and distributors of the latest subcultural styles. London’s Carnaby Street is host to a veritable explosion of street-fashion retailers and shops with psychedelic/baroque names like “I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet,” “Lord John” and “Granny Takes A Trip.” Meanwhile, the ultra-conservative UK press is shaken by the arrival of a new breed of lifestyle magazine aimed at the youth market. It and Oz are just two of the best known examples, both partly modeled on American underground journals like Rolling Stone, but placing their own British spin on the proceedings. The U.S. version of hippiedom tends toward an utopic flight out of time, but the British freaks are always concerned with a scrupulous charting of their spatio-temporal coordinates. Oz is exemplary in this regard: its name alone suggests both a fantastic outland and a specifically Victorian notion of British individualism and eccentricity.

This is the terrain that Pop Art precursors like Peter Blake and the British Independent Group (IG) set out to mine, and what qualifies them to design the covers for The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper (Blake) and The Beatles, the “White Album” (Richard Hamilton) respectively. In music, fashion and publishing — the commercially-driven sector of “low- pop”— the sources of British youth culture disclose a crucial component of nationalistic nostalgia. If there is a generational confrontation taking place here, it differs very significantly from the one being staged across the Atlantic. Michael Bracewell locates the spirit of the age within those famous time-warp photographs of Jewish Lithuanian émigré Dorothy Bohm, her visions of “Swinging London” steeped in “Victoriana and antique bric-a-brac… as much as the Regency styling of pop fashions and the vogue for art nouveau.”5 Bracewell continues, “Already, the older ladies of Knightsbridge appear somewhat shabby in their gentility, while the residue of the ‘servant classes’ display an unshakable loyalty to an orthodoxy which is no longer in place. Time and again, […] there is the sense that the younger generation are assuming the confidence of a new aristocracy, notwithstanding the obvious rigidity of London’s zoning of class.”6

Peter Blake’s cover for Sgt. Pepper might be taking its cue from these images or, more probably, from the same zeitgeist. Blake is directly responding to The Beatles’ desire for a cover to reflect their particular tastes as consumers of culture: they want to appear before a “rogue’s gallery” of their cultural heroes. In fact, Paul McCartney’s original plan is to have them posed in a classic Edwardian lounge, in front of a wall display of framed photographs. Accordingly, the band draws up a list of their guiding lights, and then commissions the Dutch design team of Marijke Koger, Jos Je Leeger and Simon Posthuma, known collectively as The Fool, to produce some suggestions as to how they might all be integrated. This first stab at the Sgt. Pepper cover meets with mixed reviews — The Fool’s run of the mill psychedelia would no longer cut it7— at which point Blake is brought in, along with his wife and occasional collabora- tor Jann Haworth, to make repairs. Clearly, The Beatles are conscious of having created something important at this point — not just an important record, but an important work of art.

It is the first time an established fine artist is contracted to design a rock and roll album cover, and his fee of £ 2,867 is likewise unprecedented. The standard rate for a Beatles cover had, up until then, come in at under £ 100, so this represents a marked increase, and the fact that the band and their various handlers are prepared to pay up suggests that they have developed a relatively sophisticated idea as to what sort of an aesthetic might now be required. It is not only the choice of Pop over Psychedelia that counts here, but the choice of an emphatically British brand of Pop, and one that is by nature much more fluid in its treatment of time and history than the American kind.

Blake’s paintings have become known for their increasingly “hands-off” deployment of populist themes and a style that openly incorporates elements of montage. As with so much British art of this period, his roots can be traced to the “Kitchen Sink” realism of painters like Stanley Spencer and the early Graham Sutherland, and to the Surrealist/ Expressionist abstraction of the later Graham Sutherland as well as Edward Burra, John Banting, Roland Penrose, etc. In the work of all of these artists, a muted everydayness prevails, even when it ventures into the sub- or unconscious. Whether it is represented “straight” or warped by way of psychic filtering, the particular version of “The Real” espoused by this generation has always tended toward a gritty grayness, and it is here that Peter Blake’s own practice suggests a substantial divergence. Not only are his paintings straight-from-the-tube colorful but also his aesthetic levity and exuberance is put into the service of a mass-market, pop-cultural content.

It is his tendency to celebrate, and in the process draw to the forefront of British Modernism, a culture that had up until then been treated as its flipside opposite, that brings Blake into the court of The Beatles. It is in effect their culture that he is celebrating, right alongside The Beatles themselves.8

For the Sgt. Pepper commission, the artist would put aside his brushes to construct instead a “painterly” photograph of the band mates, or more accurately, a collage. As opposed to “conventional” collage, however, he does not subvert our perception of a unified pictorial space. The Beatles are here posed in an actual set, surrounded by props: musical instruments, plant-life, statuettes and a whole “supporting cast” of waxwork effigies and life-sized cardboard cutouts plastered with photographic “false fronts.” The cumulative effect is reminiscent of those image-laden calling cards, or cartes-de-visite, that became popular in the mid-nineteenth century — although those were noticeably the product of a combination printing process. In contrast, the documentary “facticity” of this image, occurring as it does within a single slice of the time-space continuum, serves to align it more with cinema and the machinations of mise-en-scene.

Because the figures are actually “there,” all at once, a viewer becomes much more sensitive to the discrepancies between each of the image’s component parts. In a more conventional collage process, these would all be comprised of heterogeneous “reality fragments,” a consistent substance, that would allow for a sort of integration that pointedly does not occur here. It is precisely because the surface of this image is smooth and regular that “deeper” fissures appear, as though from underneath. Blake highlights these fault-lines by his selective and semi- arbitrary coloration. Only about half the figures assembled around The Beatles receive the full-color treatment; the rest are left black and white, all or in part. Blake’s specific choices seem random, or determined more by aesthetic considerations than content-related ones, but they also promote a finely-tuned gestalt: as the only living members of this group, the boys in the band stand out, their Day-Glo outfits commanding attention. The Beatles are the focal point of the image; they are the reason for this gathering.

As in Dorothy Bohm’s photographs, the ‘60s are here signaled by the inconsistency of the surrounding elements, evenly divided between the colored and black and white, present and past, and the New and the Old World. Most of the figures are either from the U.S. or the U.K., or else, like Karl Marx, Hugo Ball and Carlos “The Jackal,” they have managed to “cross-over.” If, barring a few exceptions, The Beatles’ culture can fit into the last hundred and some years, this is because it is essentially a mass-culture of mechanical reproduction. Regardless of their sources of celebrity, these figures become known to The Beatles as photographic likenesses. Whether they are musicians,poets, actors, politicians, gurus or even terrorists, it is by way of their own images that they gain access to the Sgt. Pepper cover shoot. In this they are united, the band and their cultural pantheon: all are essentially producers of images.

This is a Pop tableau, one occupied by mass-media icons, a particular cadre of individuals that has been able to mobilize the public’s imagination, and not only by way of their works, but by conjoining these works to a range of finely articulated personae. All of them are progenitors of a new skill: the control of one’s own mediation. Their presence here makes a point that will become more evident in years to come: celebrity marks the next step on the social, and perhaps even evolutionary, ladder. The Beatles and the figures that surround them comprise a whole new state of being, a higher state, and one that implicitly transcends Bracewell’s “zoning of class.” In every sense, then, the band is here “assuming the confidence of a new aristocracy.” This is the portrait of a new court, one comprised of disposable images in a manner befitting its popular, mediated source.

Dave Muller, Lower Right Corner, 2004

8. Court portrait, class photograph

The cover’s themes of social aspiration and transgression are established early on in the Edwardian tone and context of Paul McCartney’s initial concept. The photographic “rogue’s gallery” remains, but the decision to render these influential figures as life-size cardboard cutouts and pose them “outside,” between a soil and flower-filled strip of “ground” below and an even blue bit of “sky” above, is significant. The “rogues” are “realized” within the space of the single frame that now surrounds them all, and they become present to each other in the “here and now.” Mediation warps one’s sense of historical passage in precisely this way: by disassembling it into a collection of discrete images that are fragmentary in regard to their specific referents, but continuous in regard to each other. As images, the motley collection of figures that the Sgt. Pepper cover collages together really do form a community, a court.

Or maybe it is a class photograph — let’s call it “Media 101.” The Beatles are famous for being bad students, a generic ingredient of the rock and roll pedigree, but here it gains a particular emphasis. John Lennon mentions his early experience of school as painful and decisive. His failure to “measure up” to the expected academic standards, his alienation from his classmates, his frequent collisions with authority — all of these factors provide the impetus for his subsequent fame. Even after he has “made the grade,” as it were, he continues to think, write and sing vengefully. Lennon’s taste for absurdist verse can itself be understood as a slap in the face of institutional reason. The lyrics to “I Am The Walrus,” for instance, are adapted from a crude schoolboy song that had been composed as a farcical reprieve from the canonical high-mindedness of a force- fed diet of Milton and Shakespeare: “Yellow matter custard, green slop pie, / All mixed together with a dead dog’s eye, / Slap it on a butty, ten-foot thick, / Then wash it all down with a cup of cold sick.” Lennon found the whole prospect of a rock and roll hermeneutics ridiculous, and this song is his cynical response: “Let the fuckers work that one out.” 9

Who, exactly, are these “fuckers”? They are the academic representatives of “the establishment,” figures of institu- tional power in its most naked state; this is whom John Lennon is writing for, or rather, against. What makes school so hateful, to him, is not that it is difficult or challenging, but that it is not. Too quickly, it labeled him just another scruffy no-hoper, more deserving of rehabili- tation than education per se. School marked him in the explicit terms of social standing and class, a dismal diagnosis, although clearly Lennon had already made other plans.

“Media 101” is a photograph of a new class in social terms, then, this one defined by merit rather than birth. It is a fantasy, of course, but not without glimmers of real future potential. This incentive is embedded within the deep structure of rock and roll, with its roots in slave-song, and in conditions of an ultimate oppression. For The Beatles, this original promise of rock must undergo a translation into the specific terms of British class war. In Paul McCartney’s Edwardian lodge, the social implications of this shift are more directly registered, perhaps, but Peter Blake’s final design for the Sgt. Pepper cover is no less attentive to just what is at stake, as class increasingly becomes a matter of cultural consumption.

The abundance of U.S. subjects included in the cover is no doubt a source of anxiety to the protectivist UK mindset, determined as it is to retain some semblance of national identity in the face of the postwar onslaught of Americanization. The influx of American goods and services, American consumerism and, most distressing of all, American spectacle, mounts steadily in volume and intensity as we approach 1967, the record release date. The art establishment in Britain responds with a policy of strict containment, a move that will endear it to those at the upper end of the class divide, while alienating it further from the rest.

Edward Alloway, the British critic and core Independent Group member, offers this assessment: “The abundance of twentieth-century communications is an embarrassment to the traditionally educated custodian of culture. The aesthetics of plenty oppose a very strong tradition that dramatizes the arts as the possession of an elite. These ‘keepers of the flame’ master a central (not too large) body of cultural knowledge, meditate on it, and pass it on intact (possibly a little enlarged) to the children of the elite. However, mass production techniques, applied to accurately repeatable words, pictures and music, have resulted in an expendable multitude of signs and symbols. To approach this exploding field with Renaissance-based ideas of the uniqueness of art is crippling.”10 The argument is familiar enough; clearly Alloway has read his Walter Benjamin, but, couched in his celebration of “mechanical reproduction,” or “technical reproducibility,” is a pointed critique of British classism, a condition that is entirely sanctioned by the reigning schools of “high art,” according to him. In the face of reproducibility, “high art” has opted to cultivate its uniqueness, its “aura.” It has simply avoided the challenge of technology, offering up the flimsiest rationale by way of excuse: that of dehumanization. It wants us to believe that mechanical reproduction must lead to a proliferation of automaton viewers. “Fear of the Amorphous Audience is fed by the word ‘mass,’” writes Alloway.11 If Art remains oblivious to technological developments, in favor of an increasingly desiccated and irrelevant humanism, its stubbornness will be its undoing.

Dave Muller, As It Lays, 2004

This is a complaint that can no longer touch the Independent Group, nor Peter Blake, nor The Beatles. They have all responded enthusiastically to the challenge of the new information technologies. All have devised strategies to reconcile the new mass-media — newspapers and cinema, pulp paperbacks and pinups, disposable imagery from the weekly magazines, and the like — to the demands of an “advanced” art practice. If this new pluralism opens the way as well to the floodgates of Americanization, then so be it.

At the same time, the courtly or classroom grouping of the Sgt. Pepper album cover bespeaks a somewhat longer timeline: enfolded in an antique Edwardian aesthetic, even the youngest Americans are seen to spring from the womb of motherland Britannia. Even if they happened to follow their star to the “New Country,” that is, they are still just the latest versions of the British individual and eccentric. This point can be made consistently throughout Peter Blake’s work. As Simon Frith and Howard Horne suggest in their seminal book on the subject, Art into Pop: “Even when Blake used American imagery (like rock ‘n’ roll stars) he absorbed them in the British world of cigarette cards, bedroom walls and seaside display.”12 A similar sort of absorption occurs in the work of the IG, only varying in tenor. “Differences between Pop art styles thus [depend] on different sorts of plunder: compare Hamilton’s intellectual response to the Americanization of visual language and Peter Blake’s sentimental use of the old English designs of fairground machinery and shop fronts.” 13 In effect, it makes perfect sense for The Beatles to begin their excavation of the art-into-pop and pop-into-art interzones with the more “sentimental” Blake, and then to move on to the more “intellectual” Hamilton for their so-called ‘American’ “White Album.”

On Peter Blake’s Sgt. Pepper album cover, the gathered figures, American or British, form a public that has come to hear The Beatles, in their “starring role” as über-celebrities. At the head of the court, in the front of the class, The Beatles stir up all their influences as though in a great cauldron, and drink down the outcome as their pre-show elixir. In this way, the cultural past is shown to feed directly into this present, this moment. Every surrounding personality and star, regardless of their country of origin, is merely rehearsing the celebrity that will be enacted ultimately by The Beatles. It is almost as though the band were draining the color out of their enfolding public, to stand before us that much more vividly and life-like. They stand there, instruments at the ready, but ultimately frozen just like all the rest.

Of course they are. Nothing much can actually happen in a photograph, even if it comes with a complimentary soundtrack. Nothing but a vague perceptual fluttering: the vibrating borders of colors and shapes, the back and forth movement of figure and ground. The Beatles come apart from the crowd — they seem to emerge thanks to their sharper contours, their saturated coloration — but in the very next moment, they seem to dissolve. Just like the photograph that closes Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining, this one can literally consume its contents, the boys in the band right alongside their public, eclipsing their presence in the “real world.” How can we ignore the fact that The Beatles are turned in the same direction as this audience they are supposed to be playing to? In this frozen moment, anxious and/or pregnant, both The Beatles and their enfolding assembly of superstars have turned to face a single unknown and unknowable source — the solitary cipher holding the album.

Jan Tumlir is an art writer based in Los Angeles. One of the original editors of X-TRA, he also contributes regularly to Artforum, Frieze and Flash Art.

Dave Muller is a Highland Park artist. He is represented by Blum and Poe in LA, Murray Guy in NY and The Approach in London.