It seems hard to believe that avant-garde playwright Charles Ludlam kept anything in the closet, but there they sat for 23 years: two reels from a nascent foray into filmmaking. These madcap films, Museum of Wax and The Sorrows of Dolores, were liberated earlier this year. Digitally restored by Ira Sachs and Adam Baran in cooperation with Ludlam’s former partner and collaborator, Everett Quinton, the films were screened as part of the Queer/ Art/Film series at the IFC Center in New York on February 22, 2010.1 As a playwright and director of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company, Ludlam was a seminal figure in literary and avant-garde theater circles. His influence on contemporary art might be under the radar, but a closer look at his influence on contemporary performance art, as evidenced by Charles Atlas, Leigh Bowery, Antony Hegarty (who introduced the IFC screening), and Ryan Trecartin, attests to Ludlam’s fine art legacy. The recovery of Ludlam’s films introduces time-based works through which to study Ludlam’s ecstatic critical practice.

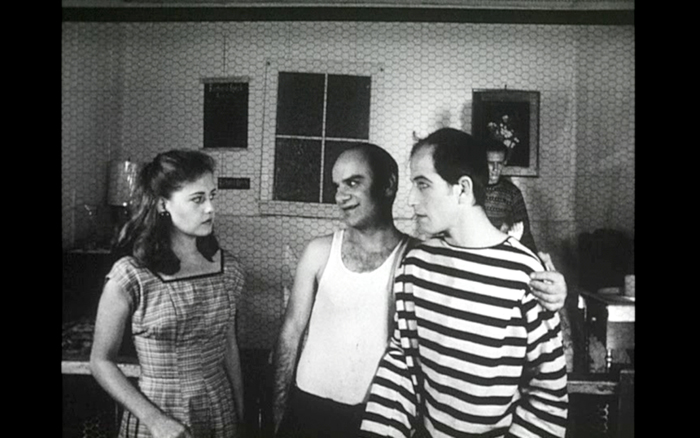

Still from The Sorrows Of Dolores, circa 1979-87, directed by Charles Ludlam. Black-and-white, 16 mm film, 80:00 min. Courtesy of The Estate of Charles Ludlam and Queer/Art/Film. © The Estate of Charles Ludlam.

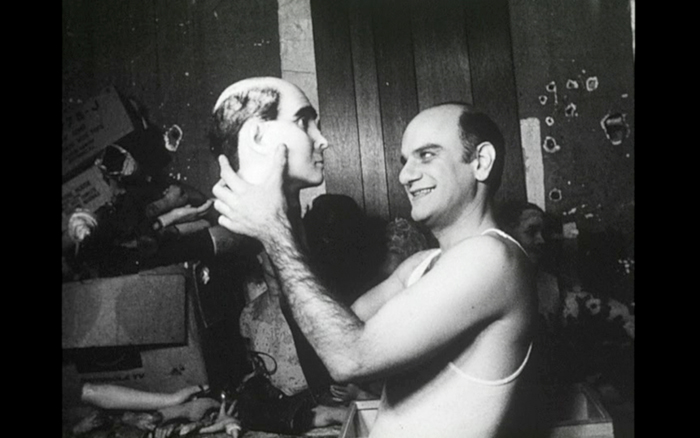

Still from Museum Of Wax, 1981-1987, directed by Charles Ludlam. Black-and-white, 16 mm film, 21:00 min. Courtesy of The Estate of Charles Ludlam and Queer/Art/Film. © The Estate of Charles Ludlam.

Ludlam began his theatrical career in the mid 1960s in New York when he joined the Play-House of the Ridiculous, a company formed by John Vaccaro and Ronald Tavel (who was also a screenwriter on many Warhol films). After numerous altercations and a single run of his first original production (the memorable Big Hotel, which featured Jack Smith and Mario Montez), Ludlum broke from Vaccaro and formed his own troupe. Staging his own follow-up script for Big Hotel–which was produced concurrently by the Play-House–Ludlam amended the title of this second play, Conquest of the Universe, to sum up the split: When Queens Collide. His troupe, the Ridiculous Theatrical Company, went on to numerous successful runs over the next two decades. (Their play The Mystery of Irma Vep received many awards, including an Obie–one of six earned by Ludlam–and it remains the most performed play of all time in Brazil).2

Before his death in 1987, Ludlam spent his last decade assembling his crew for small film shoots and editing the footage. A screening of his films took place at Anthology Film Archives on April 30, 1987, although Ludlam was unable to attend. He was admitted to the hospital on the night of the screening and died of AIDS related pneumonia on May 28, 1987. Quinton remarked after the recent IFC Center screening that if Ludlam hadn’t died when he did, “I think he would have become a filmmaker.”3

Ludlam once famously incanted of pioneering underground filmmaker and performance artist Jack Smith, “Jack is the daddy of us all.”4 Smith offers a natural entry point to examine Ludlam’s similarly camp style. Smith’s wildly baroque films Normal Love (1963-64) and the banned Flaming Creatures (1962-63) were flamboyantly personal love letters to a Hollywood of yesteryear; his works inspired countless filmmakers and artists as diverse as Tony Conrad, Robert Wilson, Penny Arcade, and Mike Kelley. His infamous performances appeared haphazard and unpredictable, often starting several hours overdue (if at all). A production of Ghosts (1977) featured a cast of stuffed animals performing a canonical work by Ibsen.5 Smith left many of his films open-ended, editing the film stock for each screening from the projection booth and producing a live soundtrack with a bizarre collection of old 45s. But these irascible approaches to performance and filmmaking displayed a rigorous form of anti-aesthetic that Ludlam embraced with gusto. Smith’s productions utilized vertiginous baroque performance strategies, set decor, and filming techniques to transform the chaos and clutter of his destitute arrangements into a vital space of utopian fantasy.

Still from Museum Of Wax, 1981-1987, directed by Charles Ludlam. Black-and-white, 16 mm film, 21:00 min. Courtesy of The Estate of Charles Ludlam and Queer/Art/Film. © The Estate of Charles Ludlam.

Smith and Ludlam shared a love for the ’40s Queen of Technicolor, Maria Montez, a Dominican performer whose limited classical acting capabilities and evident narcissism upstaged the illusion posed by gaudy sets in films such as White Savage (1942) and Cobra Woman (1943). The Siren of Atlantis was known for her ravishing beauty and she excitedly took to the fantasy of narrative worlds that made her the object of worship. Smith wrote, “One of her atrocious acting sighs suffused a thousand tons of dead plaster with imaginative life and truth.”6 For some, however, her pleasure seemed to burn too bright. Perhaps her oft-quoted exclamation: “When I look at myself, I am so beautiful, I scream with joy!” best indicates the libidinal levels of her performance. Ludlam and Smith embraced the narrative digressions offered by Montez’s films and other popular fantasy and sci-fi movies of the ’30s and ’40s. They reproduced this affinity in their flaming melodramas, which were parodic alternatives to the moralistic banality of the everyday and the sobriety of the Modernist avant-garde.

A collage aesthetic also dominated underground films of the 1960s. Joseph Cornell’s assemblage film Rose Hobart (1936) was taken up by the avant-garde as a rubric for combining bits and pieces of otherworks to create a new whole. By excising all the scenes from the narrative Hollywood feature East of Borneo (1931), save those featuring its luscious lead Rose Hobart, Cornell exposed the meticulous (perhaps fetishistic) nature of fandom by isolating the beauty of the individual performance. His pointed refashioning of these clips generated a work of psychological (self)portraiture. Andy Warhol took film narratives employed by the mainstream studio system to fabulously metaphoric levels, setting them loose on the mid-town arts scene of The Factory. Warhol’s films such as Tarzan and Jane Regained…Sort Of (1964), Batman/Dracula (1964, starring Jack Smith), and More Milk, Yvette (1966, starring Mario Montez [Rene Rivera] as Lana Turner) mash-up discernable Hollywood scenarios, star intertextuality, and scenester gossip in Warhol’s own budding production system. The conflagration of recycled matinee storylines, tabloid biography, and self-performativity regenerated star vehicles out of outmoded movie hokum.7 The point of these works is not linearity, per se, but the perpetual fluctuation between the actors’ superstar personas and the roles they were meant to perform. Like Warhol, Ludlam collaborated with many notable personalities in his Ridiculous troupe. And like Warhol’s roster, their personas and performative idiosyncrasies swirled well beyond any narrative incarnations. Filmmaker Jose Rodriguez-Soltero cast various members of the troupe in Lupe (1966) (a.k.a. Life, Death and Assumption of Lupe Velez, which featured Ludlam, Bill Vehr, and Mario Montez as Lupe Velez). In the film, the ill-fated Velez becomes a platform for a startlingly frank intersection of everyday life and stardom, fantasy and transcendence.

Ludlam’s films provide the most intimate and cohesive documents of his significant performance style. Over-acting was perhaps his most studied tool; his spasmodic performance of ecstatic jouissance elaborated upon the libidinal devices that breached Hollywood’s most generic narratives. (Overt performance and voluptuousness was not something that the Hays Code could pinpoint as objectionable. Thus, with their excessive performances and embellished physiognomy, figures like Maria Montez or Jayne Mansfield surpassed the tepid eroticism of the orientalist adventures or crime world picaresques in which they starred.) Ludlam earnestly aped these hyperbolic performances in his films.8 Privileging the tacky spectacles that enabled these performative tics to tear through filmic fiction, Ludlam transformed such gestures into an alternative aesthetic language. This ecstatic mode refutes the passive viewing patterns of escapism that were the intent of such cinemas and rearticulates their forbidden pleasures. If cinema is more or less a fantastic mirror of popular culture, then the playful magnification of these exotic impulses generates a space respective of Ludlam’s queer countercultural perspective.9 While the familiar is evoked in his cinema, its overexertion configured a new language from these popular values and styles.

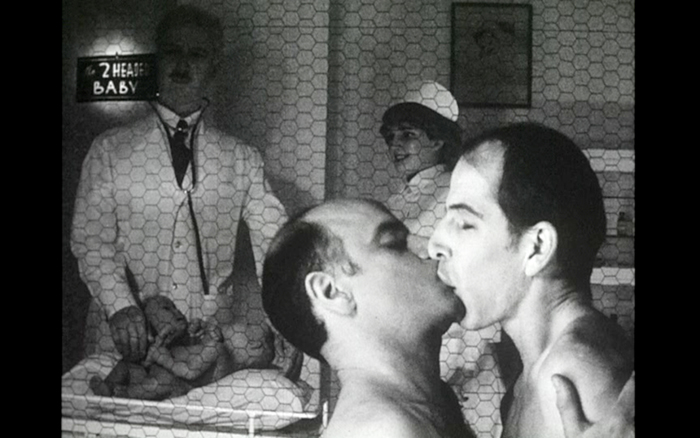

Still from Museum Of Wax, 1981-1987, directed by Charles Ludlam. Black-and-white, 16 mm film, 21:00 min. Courtesy of The Estate of Charles Ludlam and Queer/Art/Film. © The Estate of Charles Ludlam.

The black-and-white, silent short, Museum of Wax (1981-1987), is the more classically structured of Ludlam’s recovered films. Fluently adopting a silent-era cinematic language, the vaudevillian narrative follows an escaped prisoner (Ludlam) who seeks refuge in a Coney Island wax museum. The set-up is a clever ploy to involve the rows of wax puppets (and boxes of celebrity heads) in a whimsical deracination of gender conventions. Ludlam, who was initially noted for his critical use of drag and cross-dressing gestures in underground theater, slips between male and female roles, kissing his female love interest and mothering her just the same. The amorous dynamic between the damsel and her criminal lover gets more complicated after the prisoner’s former cell mate (Everett Quinton) seeks similar asylum.

The feature-length The Sorrows of Dolores (roughly 1979-87),10 is the tale of one woman’s perseverance through many death-defying circumstances, ultimately leading her to find that there’s no place like home. Dolores is an exquisitely handmade, self-conscious retooling of The Perils of Pauline (1914), a twenty-reel commercial adventure serial. The heroine “Pauline” was a subject (and product) of the industrial revolution who overcame weekly catastrophes. She bounded from moving trains, disarmed bombs, and evaded attacks from Native American hordes. Seventy years later, Pauline is recast as Dolores (Everett Quinton), a diminutive transvestite. Like Pauline, Dolores faces a succession of perils including an abusive foster parent, a murderous masked man, gypsy rulers of a white- slave trade, surly peers in a prostitution ring, nuns, savage natives, and, of course, King Kong.

Still from The Sorrows Of Dolores, circa 1979-87, directed by Charles Ludlam. Black-and-white, 16 mm film, 80:00 min. Courtesy of The Estate of Charles Ludlam and Queer/Art/Film. © The Estate of Charles Ludlam.

The overzealous performance tactics and handmade appearance of these film worlds collide with their surprisingly rigorous formalism. Contrary to the tendency towards loose, expressionistic editing patterns and camerawork that typify much narrative-based underground film, Ludlam’s films exhibit the structural conventions of early commercial cinema. The nighttime action sequences in Dolores are adeptly photographed and edited with a nuanced construction of cinematic space and tremulous tempo. As Dolores flees her masked assailant, the chiaroscuro recesses of the West Village are reminiscent of the urban mise-en-scene of a silent Von Sternberg film, or the 1940s productions of Val Lewton.11 Such methodical editing mimics its silent model, while the outmoded timing register comedically draws out narrative action, inflating the epic feeling of Dolores.

Both of Ludlam’s films utilize the most basic materials to construct scenes. With continuity errors and on-the-fly story changes, Ludlam’s copycat worlds are anything but mimetic. Dolores was made episodically, over long periods of time, and over the last decade of Ludlam’s life, he always toured with Dolores in a duffel bag, lest the perfect moment for an adventure sequence pass them by.12 The crudely constructed sets amplify the artificiality of Maria Montez’s plaster play lands. This conflict between his studied fidelity to Hollywood models and the boorish appearance of these subjects lends a wryly critical incongruence to the works. The clash sends up the artificiality and conservative ideologies behind many mass-produced fantasies. Ludlam exaggerates mainstream cinema’s tacky tendencies to the point of failure, freeing the scene from the economy of commercial fantasy. As the performers dive down the rabbit hole of their ebullient delight, lost in the throes of some serious fantasy, the cardboard sets become so visually implausible that fantasy itself emerges as the content. The performer’s play takes center stage. As such, Ludlam’s films document imagination in an attempt to film intensely personal sensations. His fidelity to industrial models enacts a cinematic equivalent to his drag tactics. Ludlam and his troupe performed a glamorous disavowal of quotidian life into a defiant form of fantasy. It’s a sophisticated business, this playfulness.

Still from The Sorrows Of Dolores, circa 1979-87, directed by Charles Ludlam. Black-and-white, 16 mm film, 80:00 min. Courtesy of The Estate of Charles Ludlam and Queer/Art/Film. © The Estate of Charles Ludlam.

Because of Ludlam’s studied bifurcation between tactics and spaces–part experimental formula, part commercial, part downtown theater scene, part avant-garde film–these works are truly remarkable “lost” objects. Their recovery provides an integral case in understanding the transition of countercinema from the underground films in the 1960s (by filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger, Mike and George Kuchar, and Jack Smith) into more commercial formats that parody the mainstream, seen in the midnight movies of Alejandro Jodorowsky and John Waters in the 1970s. Poised between conventions, the films are transitory products. They feel at once as if they emerged from the 1960s period of artistic production, and yet they betray the formula of the experimental films of the 1970s in their abidance by the feature-length narrative format (Dolores) and industrial editing patterns.

Ultimately, Ludlam’s films convey his greatest contribution to the arts: his wildly imaginative performance style. Performance artist and musician Antony Hegarty, who presented the films and co-organized their revival screening, joked that these lost works were the most influential films he’d never seen. The lost films of Charles Ludlam cloak this hysterical play-acting in the formal conventions respective of Hollywood cinema. Hyperbolic pathos emerges between the heartfelt performances and the handmade world. This chasm locates fantasy as a kind of emotional truth, whereas, in mainstream cinemas, such incongruity is typically branded a disruption. An example of this is found as Dolores faces-off with the great King Kong. The longer the take is held, the more the crude papier-mache beast unravels in front of Ludlam’s probing lens. Quinton, as Dolores, screams and flails, screams and flails. Mimesis is missing the point, which was pleasure, all along. Revising narrative based, normative cinema, Ludlam produced a revelatory sensation-based cinema without counterpoint in the breadth of avant-garde cinematic production. Our gain is ridiculous.

Bradford Nordeen is a New York based programmer and moving image scholar. His focus rests on intersections between avant garde cinema and popular culture. He is the author of a collection of essays, Fever Pitch (Free4fags Press, 2008) and has articles forthcoming in FANZINE, Film Philosophy, and Animal Shelter (with Kevin Killian).