I. The Lightning Field and Real Estate

About six years ago, I visited Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field (1977) in western New Mexico.1 From Albuquerque, I drove to the Dia Art Foundation office in Quemado with a few friends. There, a van came to pick us up, and we were passengers for a two-hour ride to a place with coordinates that were unknown to us. We were dropped off at a cabin in the middle of a flat, open, and dry landscape. The cabin had three bedrooms. In the kitchen was a pan of mediocre enchiladas for dinner and supplies for breakfast. We spent the night in this rustic, sparsely furnished cabin, found a way into the “secret attic,” and lay outdoors in blankets stargazing until the cold drove us inside. The next day, the same van picked us up and took us away again.

Outside of the cabin is The Lightning Field. Four hundred 20-foot-tall stainless steel rods arise from the earth, spaced out from one another as if marking the points of intersection on a grid. The horizon stretches out from these rods and the cabin as far as the eye can see on all sides. The idea, as I understand it, is that during storm season, this field is a perfect place to watch the lightning crack across the sky—and a rod might draw a lightning bolt to it. The Lightning Field lore has it that lightning has only ever touched one of the rods once, and then the rod needed to be replaced at great cost. The Lightning Field is therefore, in a sense, a hypothetical experience, insofar as it means to launch you into a meditation on an event that will almost certainly not take place. It is also, in another sense, a symbolic one, as it prompts you to contemplate how this field full of very orderly rods itself sculpturally evokes a field of lightning bolts more than it creates an actual relationship between lightning and the earth. When I visited The Lightning Field, however, the place launched me into a very different line of reflections related to my research on the creation of the US property system. By then, I had already for some time been studying how real estate was produced through processes of dispossession and the legal mechanisms that settlers developed and used to appropriate land from indigenous people. The content of my writing has to do with how the fate of particular parcels of land is commonly determined today by the workings of the market, which operates according to a narrow understanding of land as a commodity to buy or sell. I describe the early history of this particular idea and these practices in order to emphasize how limited and recent they are, with the aim of showing how they were introduced into a context of older and ongoing, more expansive understandings of land and all the ways that it supports human and nonhuman life.

Walter De Maria, The Lightning Field, 1977. Long-term installation, western New Mexico. © The Estate of Walter De Maria. Photo: John Cliett, courtesy of Dia Art Foundation, New York.

The idea of land as a commodity to be bought or sold has its roots in the enclosure movement in England, which began as early as the twelfth century and culminated in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Karl Marx and Karl Polanyi, among others, identified the enclosure as a key development in the history of dispossession. Yet neither thinker dwelt on how before Europeans crossed the Atlantic and established settlements in America, native nations did not conceive of land as an object that could be owned and divided into pieces for exclusive use. Colonists introduced this concept when they arrived on the Eastern Seaboard. Boundaries are critical to the concept of an enclosure: in order for land to be owned, you need to know how much of it there is. You must measure property in order to reach agreements with others about where its edges lie, to know where one person’s property stops and another’s begins.

The conversion of this land into a set of discrete parcels was a massive and often unwieldy undertaking. For many decades in the colonies, the logistical challenges of distinguishing claims meant that boundaries were more conceptual than actual; they were shifting, flexible, and generated much dispute. Eventually, surveyors, some trained well and some not at all, went out and did their best to impose something like a grid on nature, which does not run in straight lines. For scores of years, these men attempted to measure out uniform enclosures, embracing the idea that an imperfect survey was better than none, by throwing down 22-yard chains on irregularly sloping hills, and frequently facing such challenges as attempting to make these measurements across a cliff or a swamp.

The biggest obstacle to settlers’ ownership claims, however, was not the difficulty of the project of measuring all the lands in America, but the fact that the land was already inhabited by manifold communities who found this project confounding and resisted it, conceptually, physically, and with arms. Though settlers, amongst Europeans, had already formally claimed the lands under the doctrine of discovery before they arrived, these claims were of little use to them when they were not in actual possession or control of the lands. As settlers in the colonies and, later, the United States frequently lacked the financial and human resources to pursue direct military conquest of the lands, they sought more gradual and piecemeal ways of ousting the native inhabitants.

Border fence at the outskirts of El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, April 2012. Photo: K-Sue Park.

Colonial governments and, later, the United States therefore created structures of incentives to bring settlers into occupied indigenous territories. In actuality, the process was highly chaotic. In theory, however, surveyors went out first to learn about the land’s general contours, record its features, and lay a grid upon it. The government then promised settlers that it would eventually sell them plots of land if they settled upon the land and “cultivated” it. Cultivating the land meant entering onto others’ territories and clearing forests, building cabins, and raising fences there. It meant laying claim to a piece of land and defending it against others—other settlers but also, especially, tribes who called the lands home. It became the responsibility of settlers to occupy and defend the land from edge to edge and corner to corner. As they did so, they introduced diseases to which the tribes had no immunity and chased away game on which native people depended for food. Settlers made life more difficult for tribes so that later it would be easier for the colony or, later, the United States, to eke a land cession from them.

After the establishment of the United States, the federal government claimed the prerogative to regulate the distribution of land in order to control settlers’ dispersal and ensure they evenly occupied the land. By establishing land offices and appointing land officers, among other things, it then built an elaborate administrative apparatus to control the orderly progression of the frontier. The immersive environment of The Lightning Field—the landscape it inhabits and its built elements, its artificial grid and log cabin—made me feel as if I had exited the van and stepped into an open, literalized representation of this plan and of the fruits of the violent history of the survey.

Before arriving at The Lightning Field, I had no idea that this art vacation, which I joined at the last minute, would transport me to a site so evocative of exactly the subject of my research. I was astonished that the experiential fulcrum was a settler’s log cabin—where we were to sleep, under Pendleton blankets, no less. Furthermore, this cabin is situated on a tract of land that essentially constitutes a settler’s claim in the New Mexico desert. It is neither a farm nor a ranch. In fact, in having no function except as an artwork, and in its isolation from the world of art, the piece distills the very essence of a claim—the erection of a single cabin on a 40-acre tract. Forty acres: the standard unit of land that settlers eventually used to stake out claims, laid out in succession, in an even pattern of dispersal, across a vast landscape. The distribution of one family per claim meant that your neighbors lived out of sight, far away from you and from each other. Every so often, a small town still punctuates this pattern as a memorial of an infrastructure of services and supplies that helped to sustain these outliers.

View of the borders between Texas, New Mexico, and Mexico from the intersection at Mount Cristo Rey, April 2012. Photo: K-Sue Park.

What a weird and lonely formation! Contemplating De Maria’s grid led me to think about how human beings had not often settled like this, at any time or place on the globe. Rather, they most often formed towns or villages by living together and forming communities on arable land, along rivers and frequently in valleys between mountains. By contrast, this atomized pattern of settlement, this mode of spreading out across the land, struck me as distinctly American, in that it was designed by the government to further its expansion. The isolation of The Lightning Field cabin, and the sight of the open horizon, brought to mind the settler habit of clearing the land of trees for defensive purposes—in order to see interlopers approaching. The grid of rods therefore invokes not only lightning, but also the sightlines of a Western perspectival view and the mark of the surveyor’s lines on the land. It is composed of citations to the corners that identify ownership on the vaster grid, to which this plot too belongs, and to the way land came under jurisdiction of the United States. The Lightning Field therefore brings you to a site emblematic of the historical processes of indigenous land expropriation and distribution of the public lands. Yet the site is at the center of an art piece that visitors find charming and enticing, without knowing much about the history that produced its aesthetics.

Indeed, in an environment saturated by cabin porn and fantasies of living “off the grid,” the artwork seems to encourage you to enjoy your stay there, in the artificial isolation created by the patterns of settlers’ claims and in a space that accentuates the atomization of human life. The experience works by imposing an interface between physical and abstract space that brings you into a temporal horizon disconnected from your daily life and, moreover, that disconnects you from the material history of the land. Yet nothing could in fact bring you more squarely within the grid, for the lines at once echo the patterns of the surveyors’ grid and draw the four corners of a blank slate, also ripe for a Western horizon and view. The artwork, this canvas, is three dimensions running into the distance, the horizon blurring in the heat. It therefore conjures the space of the museum, a container for an aesthetic exposure distinguished from the world at large, ready for presuppositions that make it harder to question the work’s fundamental connection to the colonial understanding of America as a place of free, vacant lands. In this way, The Lightning Field presents an experience of the land that is romanticized, commodified, specialized, and rarefied into a history-less meditation on space, nature, and the universal self.

II. The Border and Real Estate

A few years after I visited The Lightning Field, I went to the desert again, this time for a longer term, to practice foreclosure and eviction defense law on the border. I moved to El Paso, Texas, a city that sits at the end of the Rockies, in the Chihuahua desert. Driving up from a distance, you can see the outlines of the mountain range in clear relief against the sky and desert; and you see a valley with a river running through it between mountains that look like they are in conversation. As you approach the mountains, you eventually find a sprawling city, and you understand perfectly why people would seek shelter there, especially in such a dry, dusty, and relentlessly sunny climate. From this distance, the city looks like many other places in which peoples around the world have settled since time immemorial.

It isn’t until you draw closer that you discover a fence running along the river that runs through the city. That fence, which was built in 2008, stretches out on either side of the city into the desert as far as the eye can see. That fence now artificially splits that city where people have lived together so long. It marks the border between the United States and Mexico.

View through the border fence from El Paso, Texas, to Anapra, Mexico, April 2012. Photo: K-Sue Park.

The city of El Paso wraps around the mountain in a U-shape. At its southernmost point, El Paso dips down to touch Ciudad Juárez’s downtown. At this point, a walking bridge crosses over the Rio Grande. There has been a bridge at this place since a time when the river was healthy and flowing, when it ran wide and had a shore. People traversed the bridge across it regularly without issue. These days, however, the bridge is a tightly controlled tunnel with contained sidewalks on either side of the road; and it arches over a Rio Grande that has dwindled to a polluted trickle that passes through a concrete conduit, which is lined by three rows of barbed wire fence on the US side. On the other side, Juárez sprawls out and runs up against the end of the other side of a mountain in the range. Thus the mountains sandwich the two cities.

The border bridges make everyday life so difficult that people will avoid them if they can. The guards routinely harass crossers. The lines to cross are very long. In particular, the car lines grow monstrous and force people to wait for hours to cross, idling on the bridge. This wait results from the fact that, more often than not, only two or three of the eight or nine lanes on the bridge are open, producing a bottleneck that seems never-ending.

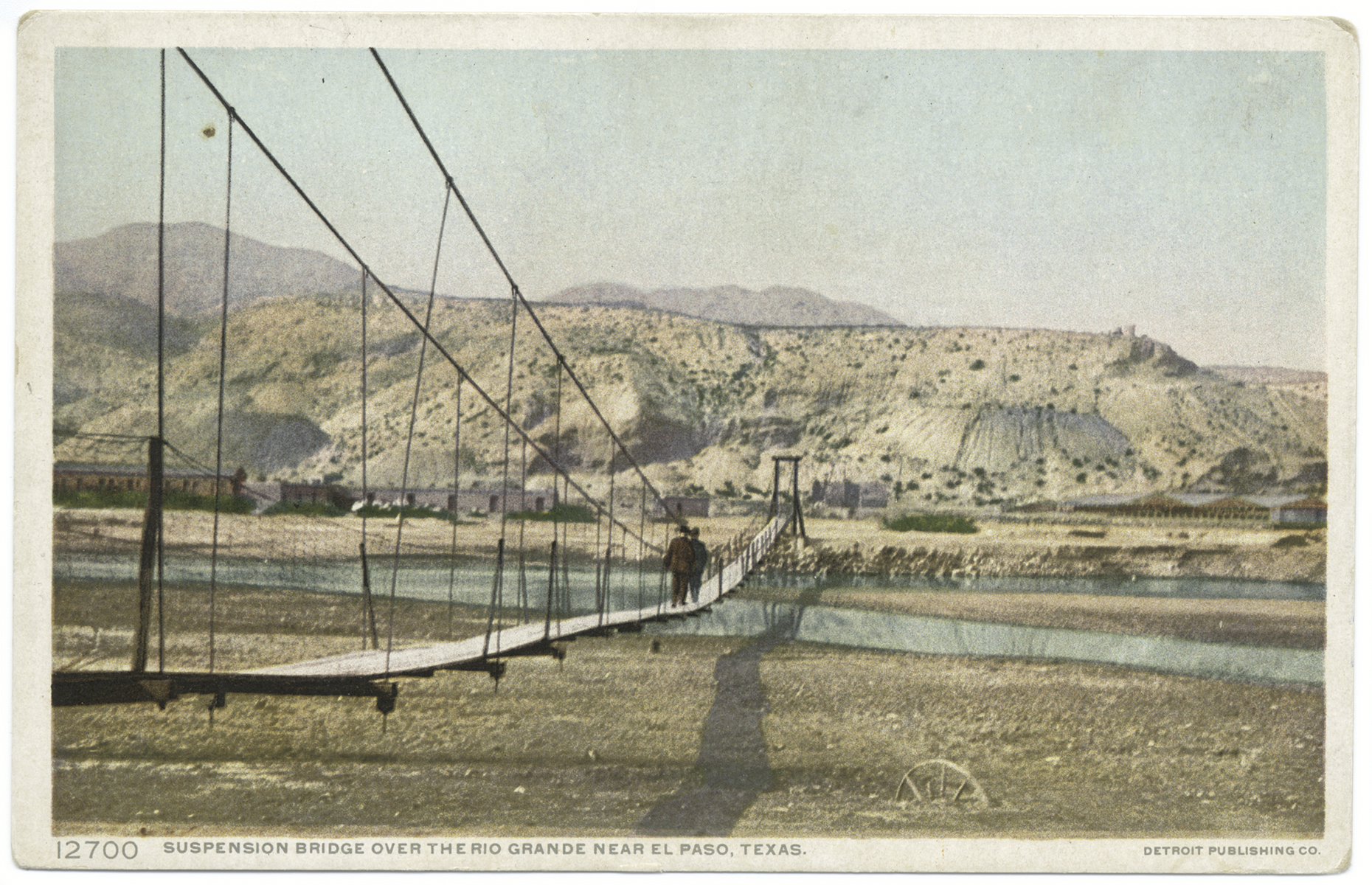

Suspension Bridge over Rio Grande, El Paso, Texas, 1898–1931. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-3546-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Bridge of the Americas (El Paso–Ciudad Juárez), June 2016. United States Department of Homeland Security. Photo: James Tourtellotte.

It is hard to overstate just how stupid and tragic most people who live in this city find this barrier at the border. The checkpoints make it harder and slower for people to do everything—from seeing their family members and going shopping, to getting to work. In this city, the border feeds on people’s time and energy, often making them tired, frustrated, and sad. Many people whose homes are near the border will spin within an orbit of life that is narrower than it would be otherwise, although the other side of the wall is in plain view at all times. Yet despite these blockages in its arteries, the city still exists as a community, even if it is now one to which it is more painful to belong. People’s family histories are still located across, underneath, and entangled with both sides of the border. The people of this place deal with the current situation as best as they can. The city is still one organism, surviving the barbed wire that is strung through its heart and that runs a jagged line through the center of its body.

When I drive along the United States’ southern border with Mexico, or cross it, or even when I see it stretch across the desert in my mind’s eye, I often think about how the real-estate system in this country sustains it. When I lived in El Paso, I could see from my front porch the border and the way the small, colorful homes in Juárez clustered together more densely than the houses on the US side. Through my eyes, the border is the geographical and historical limit of the system of real estate in the United States. It marks the territorial edge of the US empire—the far reaches of the lands that became a commodity within its private property regime. At its edges, the market changes: Mexican real estate is not as valuable as US real estate on the global market. That difference is determined not by the characteristics of the land itself but rather by the border.

Just as the firm edge defines each individual piece of private property in this system, it is also crucial to the collective state project that rendered the land mass a commodity infrastructure. The concept of the enclosure and the material project of creating borders, small and large, has been central to this land system since its earliest period. It is important to remember that those edges, even when marked by fences, remained fairly hypothetical as long as the claim was getting staked in the zone popularly called “the frontier.” According to the US Census Bureau, the frontier was any region where the population density of white settlers was less than two per square mile. In other words, it was any area with a significant native population, near or adjacent to territory more densely populated by whites. It was any region that lay just beyond the edge of lands controlled by settlers. Though it is common to hear of the “western frontier,” this settlement proceeded in any direction in which the project of conquest was deemed incomplete.

The US–Mexico border at El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez. On the US side of the Rio Grande, El Paso is marked by the brightly lit Interstate Highway I-10 that cuts across the city. NASA Photo ID: ISS006-E-44123, https://eol.jsc.nasa.gov. Courtesy of the JSC Earth Science & Remote Sensing Unit, ARES Division, Exploration Integration Science Directorate, Johnson Space Center.

Because this space was anywhere that people whose very existence challenged settler sovereignty lived, the borders that lie in the places where the frontier arrived include those that mark the limits of the sovereign territories of native nations, as the indigenous organizing group the Red Nation has pointed out.2 These borders, like the national borders of the United States that distinguish its territory from that of Mexico and of Canada, are areas where the project of conquest must still maintain itself—where it is a daily exercise to assert US sovereignty with a show of military force and violence against nationals of a competing sovereignty. This violence continues to protect not only settler jurisdiction but also the private property through which that jurisdiction was established and over which it extends. For now, every inch of land in the United States is accounted for and measured—all claimed under public or private ownership, and, at least hypothetically, all at the ultimate disposal of the state.

III. The Lightning Field and the Border

The Lightning Field and the border are two examples of land divisions that emerge out of the same history of conquest and the same system of proprietorship that supports a land market that shapes the conditions under which we all live today. Both, in other words, are consequences of the same process of converting the surface of the earth into commodified claims that now constitute the cornerstone of the global economy. The value of the US real-estate system has reached a sum of around $30 trillion. Sixty percent of all global assets are in land, and 70 percent of all bank loans made in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and Australia are mortgages. The amount of money at stake in this market cannot be overstated. It is the first type of investment that most people with disposable capital, as well as many without, will consider.

Yet people do not often think about the border in terms of real estate—and even less so The Lightning Field. In El Paso–Juárez, where the US land system rips across an organic community to separate part of it from the rest, the militarization of the border distracts from such thinking. There, the edge that maintains the US real estate system lies in the shadow of Fort Bliss, the second largest military installation in the world. A wall exists in pieces along the southern national border already, in the name of safety. Construction has begun on a taller, thicker, more imposing-looking wall than the one that marked the line between the United States and Mexico before. That wall more emphatically announces the screen of the border—this fiction with brutal consequences—which naturalizes the use of the land on either side. Further, although the intensity of the border’s militarization testifies to the property interests at stake, it explains its own necessity not as linked to the creation and preservation of wealth, but rather with reference to “safety” and the dangerous propensities of the people who attempt to cross the border.

What kind of screen is The Lightning Field? As an artwork, quite differently from the border, The Lightning Field draws mystery and attraction from the idea that it takes you out of the circulation of your life. This screen is more like a canvas: it bears the marks of a long tradition—and a history of conflict—in its grid. But, like other artworks, it also invites you to write the narrative according to your will. The Lightning Field, like the border, naturalizes the land system of the United States, but leaves the extent to which it becomes an index of this naturalization up to us. Do you want to entertain a fantasy of Nature, wild and pure, acting upon you? Does the open horizon inspire you to embrace the promise of a blank slate, an open future?

Who will ask about the everyday divisions that we traverse—or cannot traverse—across this land? Who will ask what happened in this land to establish them? As an escape from the world that real estate made, The Lightning Field sets up an experience that tends to abstract the land still further from an already highly abstracted way of moving through it. By divorcing the land from its past relationships and using fantasy to obscure its own place within a system of continuing violence all over the country and the world, The Lightning Field protects you from thinking about any of that—even as you stand right inside it.

K-Sue Park is the Critical Race Studies Fellow at the UCLA School of Law, where she teaches a seminar called Land, Displacement, and Dispossession. Her writings have appeared or are forthcoming in the Harvard Law Review, History of the Present, and Law and Social Inquiry. She thanks Jamillah James and Lanka Tattersall, for the invitation to present these ideas in a panel discussion sponsored by The Feminist Art Project; Jeanine Oleson, for helping talk the piece into existence; and Nadia Awad, for her invaluable comments and insight into the essay form.