Chiquita Canyon Landfill, California, May 2016. © 2019 Google. https://www.google.com/maps/@34.4262779,-118.6466629,3a,75y,277.88h,90.04t,0.51r/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sEzU7vnL4QCipW-luSHQl2w!2e0!7i13312!8i6656.

Painting landscapes of landfills in 2018 could be taken as a provocation in light of the renewed urgency over our ecological crisis. Likewise, the very practice of landscape painting appears as a certain type of anachronism, given the ease and disposability of digital imagery in our image-fatigued present. Susanna Battin’s painted landscapes of the Chiquita Canyon Landfill in her exhibition Key Observation Point function as just such an anachronistic provocation. Her painted scenes of the landfill tease out a particular romantic notion of landscape beauty that remains ensconced within the legal and economic regimes of power that mold and shape the American landscape.

Susanna Battin, Key Observation Point 7, 2018. Digital collage, 3000 × 2400 px. Courtesy of the artist.

Even before the twenty-first-century economy of digital imagery, the discipline of painting had long ago been decoupled from the objective representation of the material world. But Battin’s highly processed paintings of Los Angeles’s largest waste disposal site reverses this order by inserting the “hand-crafted” into the predominance of digital networked technologies that increasingly mediate how humans understand the world and each other. Instead of traveling to the landfill to paint from direct observation, Battin created them from her readings of the landfill’s Environmental Impact Report (EIR). The artist extracted key phrases from the report’s written description, such as “open grassland dotted by a small number of large trees” and “riparian vegetation along stream.”1 Battin queried these descriptions in Google’s Image Search and used the corresponding results as building blocks for the painted scenes. Using the tools of written language and networked digital infrastructures, the artist was able to render her painted images of the landfill without ever physically traveling to it.

Battin confined her search to a section of the report devoted to “Landscape Scenic Quality Scale,” a standard developed and refined by landscape architects and the Forest Service since the late twentieth century to measure the aesthetic values of landscapes in order to assess their conservation or development potentials. Using the conventions of linear perspective and predetermined rubrics—described in the report as “vividness, intactness and unity”2 —the authors of the Chiquita Canyon Landfill’s EIR analyzed seven key observation points deemed most accessible to view the landfill, thus the exhibition’s title, Key Observation Point. According to the Los Angeles Contemporary Archive exhibition statement Battin’s work excavates “how the Romantic conception of nature continues to permeate contemporary politics, ecology, and dictate the human relation to the land.”3 But Battin’s painted vistas point beyond romantic pictorial representation, exposing how it serves to depoliticize bureaucratic language. The paintings are thus grounded more in the generalities of the EIR’s bureaucratic language than in the physical contours of the actual landfill; the paintings’ true subject is how bureaucracies see a landscape, rather than the landscape itself.

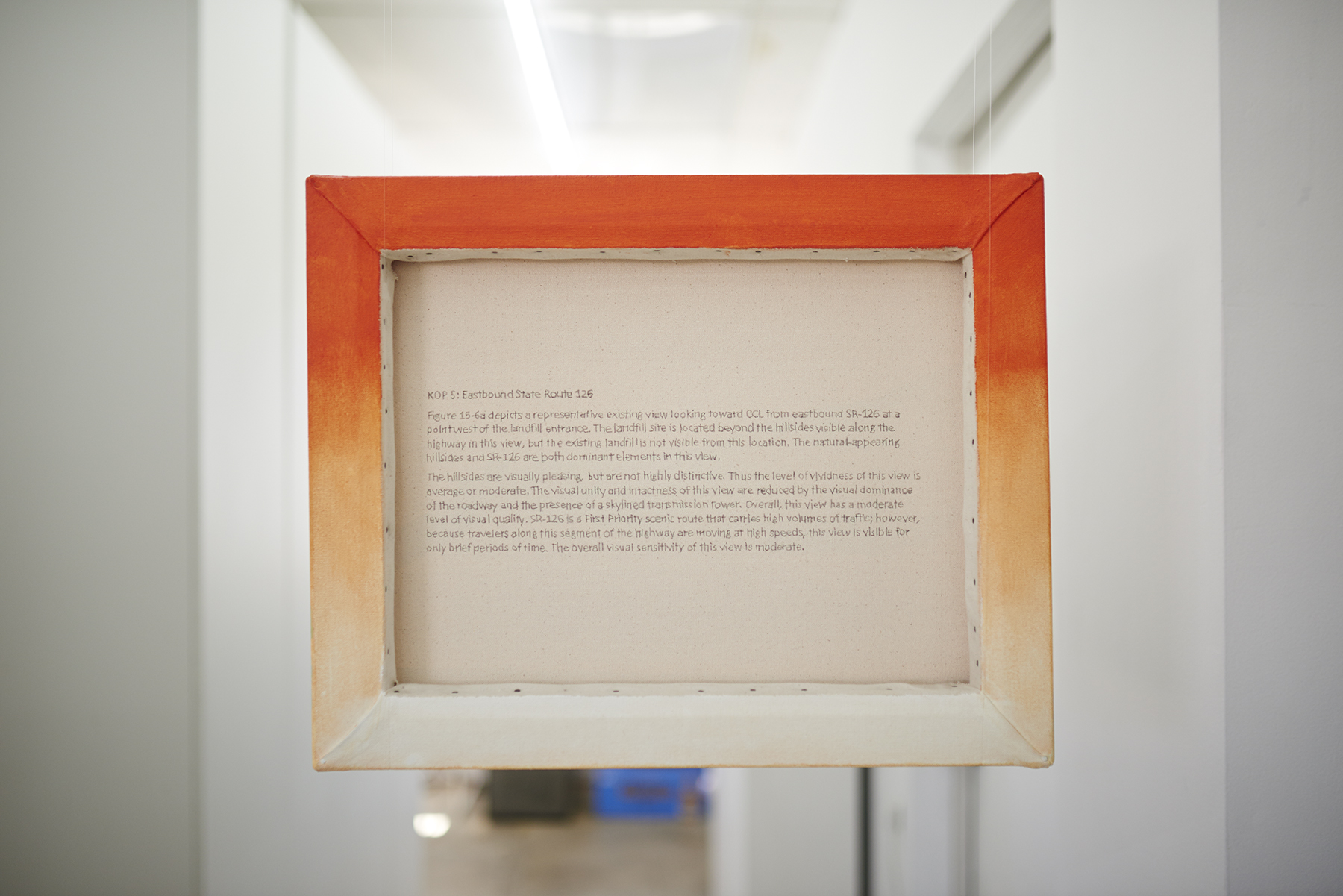

Battin’s engagement with the Chiquita Canyon Landfill spans nearly a decade. Her interventions with the site range from performance-based, video, and text works to social practice. Key Observation Point marks a departure in that it is the artist’s first foray into painting. The paintings are each oriented within the gallery space in geographical relation to the depicted view, in effect making a scale model of the landfill inside the exhibition space of Los Angeles Contemporary Archive. The canvases are suspended, allowing the viewer to experience them as objects and to access the EIR’s written description of each view, which is inscribed on the back of each canvas. Battin’s particular ambivalence toward painting can be read in the show’s emphasis on exhibition materials that lay bare the idiosyncratic process behind their construction, including a research station with a computer display and printed binders of both the report’s Landscape Scenic Quality Scale chapter in its entirety and the images Battin sourced through Google. The painted views on each canvas are composed of blocky discrete elements collaged across the canvases as if the scenes were scrapbooked. The paintings read like partial scenes, more or less complete. The entire exhibition adheres to a montage-like logic. Its subject resides neither in what is painted on the canvas, the computer screen, or the pages of the report, but rather in between these regimes of looking and understanding. This is an assembly of meaning that the German filmmaker Harun Farocki described as soft montage.4 The subject is not this or that, but rather both this and that: the relations between images and objects, written accounts, the mysterious black box of Google’s algorithmic logic, and the rendered impressions on the artist’s canvas.

But what to make of the insertion of Google’s image search into Battin’s artistic process? If the EIR’s Landscape Scenic Quality Scale represents the grafting of aesthetic judgment onto the framework of reason and logic, the image results of Google’s algorithm push this further. Battin’s querying key words from the EIR into Google’s database further suppresses the artist’s role in the translation from text to image. Like many of the decisions of contemporary life, responsibility is ceded to the guiding hand of machine logic. The final painted landscapes are quite literally “paint by numbers,” designed by the ones and zeros of Google’s algorithm. Battin’s painting process could, in fact, be seen as a cruder version of the image recognition training sets Google engineers have already been applying to their artificial intelligence systems.5

If we accept Battin’s reverse translation of the EIR’s language back into the pictorial as a prompt to reconsider the very act of looking, then the choice to insert Google’s computational logic only widens the distance between the report’s written words and the images painted by the artist’s hand. Landfills are, of course, sites for the disposal of the materially abject. Google is the world’s largest information gathering system. Both exist because of cultural, economic, and political considerations over what is and is not deemed useful, be it immaterial information or material objects. Both make profit out of waste.

Susanna Battin, Key Observation Point 5 (front), 2018. Acrylic and graphite on canvas, 16 × 20 × 1 ¾ in. Installation view, Key Observation Point, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, August 31–September 28, 2018. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Sean Sprague.

The Chiquita Canyon Landfill is a piece of public infrastructure that, despite its operation by a for-profit private company, continues to answer to the legislative oversight of Los Angeles’s municipalities and, by extension, the citizens of Los Angeles. Google, on the other hand, is privately owned and operated for profit; so far, its answerability to government or citizen oversight remains minimal. The guiding logic of the company’s search engine is that of an advertising system, not a knowledgeor evidence-based retrieval system. Google’s massive amounts of revenue are generated by the targeted advertising that is made possible with the search engine’s free service. The company does this by repackaging what was originally the unintended byproduct from Search, the “behavior surplus” of user logs or “data exhaust,” which it then bundles into predictive sets of behavior data to sell to advertisers to obtain clicks. This new digital economy of waste is what scholar Shoshana Zuboff has described as “Surveillance Capitalism.”6 Others simply call it capitalism.

Thanks to Google, if you wish to see the Chiquita Canyon Landfill but have no actual waste to dump, you, like Battin, can spare yourself the physical trip. With an internet connection and a “smart” device, you can be nearly anywhere in the world and still gaze—through layers of hardware and software protocols—out onto the southern vista of the landfill’s sculpted landscape and try to pinpoint where the Earth’s ecology and the human hand meet above the Los Angeles Basin. Google’s Street View stops just short of the entry point to the landfill weigh station, where the infrastructure of the roadway meets the infrastructure of waste management. With Google’s networked infrastructure layered on, you can virtually line up behind a couple of big rigs, but you’ll forever be stuck waiting behind them at the point where Google’s Street View car was forced to turn around. In order to push beyond this threshold, you can rise up and peer past the sculpted mounds over the horizon and down into the landfill by way of Google Earth’s god’s-eye view, thanks to Google’s partnership with the US Navy’s Global Positioning System (GPS). The limitations of linear perspective from the horizon have now been overtaken by the z-axis from above. The satellites’ perspective—once the privileged view of governmental hard power—is now instantly accessible for anyone with a computer or smart device. This is a vantage that divides the Earth and organizes physical space in order to permit, but more often, foreclose access.7 Terra transformed into dominion.

Susanna Battin, Key Observation Point 5 (back), 2018. Acrylic and graphite on canvas, 16 × 20 × 1 ¾ in. Installation view, Key Observation Point, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, August 31–September 28, 2018. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Sean Sprague.

Lucy Lippard writes: “No public place is a better gauge of a society’s values than a landfill site.” 8 The project to beautify a landfill then confronts—as much as it might also attempt to conceal—the double-sided question of not only what and why a society discards what it does, but also what and why it produces what it does. Seen in this light, a landfill is the final phase of land use as property before it’s given back to nature. What’s left over is for the wilderness. In his book, After Nature: A Politics for the Anthropocene, legal scholar Jedediah Purdy traces the intellectual history of environmentalism in the United States and pinpoints the appearance of the word wilderness in the environmental lexicon in the 1920s. Up until that point, wilderness had largely been used as a pejorative reference to the unproductive use of land, or its waste. Purdy explains how wilderness advocates constructed their legal framework for land conservation through reaching back to the language of romanticism and constructing a moral argument for encountering, seeing, and describing the landscape. Over time, this new politics of nature found an array of advocates, with interests that ranged from the spiritualism of John Muir to the progressivism of Frederick Turner, and reached its apex in Theodore Roosevelt’s enthusiasm for centralized government power.9 In effect, progressive technocrats of the twentieth century seized and built an administrative layer upon the ideological groundwork laid by the romantics of the eighteenth century. The wilderness had been created as a political project to construct an imagined “pure” natural space devoid of people or production that must be simultaneously kept separate from and protected by people through bureaucratic management. This particular utilitarian view of nature falls under what Purdy names the “environmental imagination”: the evolving ways in which humans have imagined their relation to the earth, valued it, and in turn shaped it.

Susanna Battin, Key Observation Point 2, 2018. Digital collage, 3000 × 2400 px. Courtesy of the artist.

From 1867 to 1878, geologist Clarence King organized and led the Fortieth Parallel Survey across the American Western Frontier. The survey was one of four of the Great Surveys of the Western landscape authorized by Congress on the heels of the American Civil War. The Department of War mobilized these expeditions in peacetime to scientifically analyze and document the landscape of the Western territories geologically, cartographically and visually, in order to determine how difficult Western settlement might be. Ironically, Congress’s aim was to capture a territory to which the United States had already laid claim.10 The burgeoning technology of the photographic image would document both the landscape of the frontier and the process of its capturing. Scholar Alan Trachtenberg argues that despite the scientific and journalistic intentions of the surveys’ official photographs, they also served to fuse civic and aesthetic ambitions for Western expansion under one providential view of the frontier as the rightful stage for settlement. Trachtenberg points to the relation between Timothy H. O’Sullivan’s photographs of the survey and the correspondence of survey leader Clarence King. In prose that is more reminiscent of a romantic poet than a geologist, King narrates how he named three lakes in Utah after his half-sister and her two friends. In fairy-tale-like fashion, he describes how he quested “through a dark canyon to the top of a mountain, found the lakes and bestowed the girls’ names on them, wind, trees and rocks sighing their approval.”11 King describes the sublime effect the landscape had on him, and Trachtenberg identifies how King’s sentimental response to the landscape—sanctioned by the governmental power to name the topography he encountered—drove a claim to the land that suggested both a legal and a moral authority to name it. This is an “environmental imagination” born of a European patriarchy that only understands the ground beneath one’s feet as a territory to be viewed, named, and claimed. The pictorial’s ability to convey the surveyor’s relation to the environment—be it through a landscape painting or a photograph—is preceded by a particular notion of settlement that intervenes long before one ever looks through a viewfinder, picks up a brush, or puts pen to paper.

Susanna Battin, Research Area, 2018. 2017 Final Environmental Impact Report and Master Plan Revision of the Chiquita Canyon Landfill (three-ring bound laser prints and CD-R), Gateway laptop, Internet image archive (three-ring bound laser prints and digital files) printed mouse pad, mouse. Installation view, Key Observation Point, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, August 31–September 28, 2018. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Susanna Battin.

Reconnaissance is defined as a preliminary survey to gain information, specifically, an exploratory military survey of an enemy territory. The camera reveals itself to be an essential tool in the first step in this process. Reconnaissance, and by extension the camera, work to territorialize space, objects, and subjects that sit across a border or threshold; the foreign exterior beyond the occupied interior must be identified and named in the first steps toward its ultimate acquisition and conquest. This is also the logic of empire. The Fortieth Parallel Survey, considered in its entirety—including its photographic records and data—can be understood as a crucial step toward what Thomas Jefferson envisioned as a new “Empire of Liberty” early in the American Union’s formation. Jefferson and many of the other framers of the US Constitution had formed this vision from the liberal ideas of English political philosopher John Locke. The Empire of Liberty was to be the Enlightenment manifested into a state, united by Locke’s emphasis on men’s shared preservation for their lives, liberties, and most importantly their estates. But as Lewis Lapham (among many other scholars) points out: “Locke could not conceive of freedom established on anything other than property. Neither could the eighteenth-century framers of the Constitution. By the word liberty, they meant liberty for property, not liberty for persons, and by the end of the summer of 1787, the well-to-do gentlemen in Philadelphia had drafted a document hospitable to their acquisition of more property.”12

Timothy O’Sullivan, Lake Lal and Mount Agassiz, Uinta Mountains, Utah, 1869. US National Archives and Records Administration NWDNS-77-KW-212 ARC 519650.

As much as O’Sullivan’s photographs might depict the “untouched” splendor of the Utah lakes at the end of the nineteenth century, they simultaneously conceal the historical violence and brutality visited upon those who already inhabited the land at the hands of the Empire of Liberty. In the case of Eastern Utah, this was the dispossession and colonial settlement of the Ute and Ouray tribal lands, which began under the orders of Abraham Lincoln, in 1861, and continued through the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act. Scholar and poet Fred Moten explicitly describes how the US government recognized and rationalized the incompatibility between the American project’s liberal doctrine and the indigenous relation to land through the joint acts of separation and erasure. Moten writes: “[Roosevelt] knew that possessive individualism—that the self-possessed individual, was as dangerous to Native Americans as a pox-infested blanket. Civilization, or more precisely civil society, with all its transformative hostility, was mobilized in the service of extinction, of disappearance.”13 O’Sullivan’s 1861 photograph, Lake Lal and Mount Agassiz, Uinta Mountains serves as a monument to this legacy of conquest and erasure.

Both the Chiquita Canyon Landfill and its Environmental Impact Report are the inheritors of the Empire of Liberty and its environmental imagination. The EIR’s chapter dedicated to measuring the landfill’s aesthetic value reinscribes both romantic and utilitarian views of the landscape. These two entangled views see nature both as something sublime and as the providential stage for European settlement and enlightened progress. The report’s Landscape Scenic Quality Scale therefore serves as both an ideological and pastoral camouflage to obscure not only the dirty business within the landfill but also, more importantly, our economies of waste. Battin’s Key Observation Point pokes a hole in this façade to reveal how all projects aimed toward defining nature are, in fact, expressions of power, intended to essentialize what is in fact political into something that appears natural. Her highly processed paintings of the EIR’s Landscape Scenic Quality Scale therefore provide an opportunity to repoliticize a particular way of imagining the human relationship to the land and make legible how a constructed view of the Earth has naturalized the instabilities of twenty-first-century capitalism’s hyper-productive and consumptive dynamics into something commonly accepted as destructive yet inevitable. But there is nothing inevitable about this particular arrangement of land use and these economies of waste; rather they are contingent upon a series of other political arrangements and economies. The key point from which the EIR’s authors view the landfill is not from any particular point in space, but rather from a double-sided imagined view: a romantic image that sees the wilderness to be separated apart and only looked at and a utilitarian image that renders particular economic arrangements of land use as natural.

Art critic John Berger characterized a particular ideology of romanticism as “a breathlessness of the new superstitions that protected men from the enormity of what they were discovering: above all the superstition that a feeling in the heart was somehow comparable with a storm in the sky.”14 Centuries after the invention of the steam engine, this romantic hubris has left a very real physical imprint upon the Earth. The carbon that humans have put into the atmosphere does brew storms and shape the climate. In the age of the Anthropocene, in which human behavior is now the central force shaping the Earth’s development, the distinction between the human and nonhuman world has passed. As the title of Jedediah Purdy’s book makes clear, humans have reached a point in history that is after nature. For Purdy, it therefore follows that human economies shape the Earth’s ecologies.

But as Purdy rightly points out, this must be followed by a subsequent question: What then shapes human economies? He writes: “Law is the circuit between imagination and the material world.”15 If art can serve as a vehicle to express, reflect, and imagine our relationships to our selves, to others, and to the material world, law then provides a bridge to carry these imaginations into a concrete order. The legal document, in this case the EIR, is an object that bridges imagined ideas into shaped realities. Philosopher and legal scholar Brian Butler sees the act of legal writing as an aesthetic practice that relies on sentiment as much as it lays claim to reason: “Reason is associated with distance, coolness and technical terminology. Highly stylized use of analogy and citation to legal authority attached to formalistic and explicitly ‘logical’ moves are also emphasized. What is interesting here is that the legal profession has no way to test its claims to being ruled and justified by reason other than to appeal to its own formalistic criteria.”16 In other words, reason becomes defined by the feeling of distance. Dispassion is thus codified into bureaucracy as set of formalist and aesthetic traits in the document’s appearance, which become self-evident appeals to the document’s own legitimacy, a polemic that looks to its own formal expression to justify itself. Butler’s “aesthetic of reason” provides a link between Battin’s painted vistas of the Chiquita Canyon Landfill and the EIR’s fastidious clinical analysis in written words. The paintings reverse engineer sentiment to reason and back again, and expose a perceptual feedback loop.

Susanna Battin, Key Observation Point 3, 2018. Acrylic and graphite on canvas, 16 × 20 × 1 ¾ in. Installation view, Key Observation Point, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, August 31–September 28, 2018. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Sean Sprague.

A report, much like an image, has as much potential to illuminate as it does to obfuscate. In October 2018, the United Nations released the most recent report from its Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Writing in the Boston Review, environmental historian Troy Vettese deciphers the report’s seemingly bureaucratic language to conclude that the document is in fact a radical image of the world, both as it is and what it must become. According to Vettese, property and land use lay central to the report’s analysis, in which the failings of “market mechanisms” to address the accelerating crisis and the “stranded assets” that are expected to result are made strikingly clear. For Vettese, the intentions of the report’s authors are loud and clear: “Capitalism’s insouciance toward land scarcity and climate change has forced the IPCC’s scientists to embrace planning.”17 Debates within liberal democracies over the capabilities of the planned economy have historically found the greatest traction during periods of war, such as the Socialist Calculation Debate of Red Vienna, following World War I, and the war economies of World War II. Even the Great Surveys mobilized under the US War Department during peacetime were still part of a war campaign on the frontier, both on the geology of the land and the genocides and dispossessions of the indigenous people who lived there. The word frontier originates from a military context during the Middle Ages in France, with frontière meaning the borderland or military front.

In our era of ecological crisis, the case for an emergency economic restructuring on a massive, war-like scale has once again found purchase in the revived discourses surrounding a Green New Deal and other similar calls for mobilization.18 The EIR’s Landscape Scenic Quality Scale to determine the aesthetic value of a landfill is as much a denial of the impending reality of ecological crisis as it is a denial that other ways to organize our economies, politics, and ecologies exist. Battin’s Key Observation Point provides an opportunity to confront this denial by thrusting the pictorial’s historical role onto the present age of climate catastrophe and global computational power through an anachronistic throwback. Just as there was nothing inherent in the liberal doctrine of property rights present within the trees and water that Clarence King named in the Eastern Utah Mountains, there is also nothing preordained about how technologies such as Google’s AI can be utilized in a world seeking to see itself anew, and see its way out of crisis.

Ryan S. Jeffery is a filmmaker based in Los Angeles. He has most recently taught in the School of Critical Studies at CalArts. His latest film, The Walls of the WTO, is currently in the group exhibition Say Shibboleth! On Visible and Invisible Borders, at the Jewish Museum in Munich, and is also available to view on the Verso Books blog.

Author’s Note: I would like to thank Amy Howden-Chapman, whose conversations with me contributed to many of the ideas pursued in the discussion of this work.