Psycho Salon, installation view, O-Town House, Los Angeles, September 27, 2019–January 4, 2020. Courtesy of the John Boskovich Estate and O-Town House, Los Angeles. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.

Early in his career, the late artist John Boskovich shared the roster of the iconic Los Angeles gallery Rosamund Felsen with the likes of Mike Kelley and Chris Burden. He mostly exhibited self-portraits that paired found texts and images in cryptic combinations. Despite his use of appropriated materials, a strategy that was common among his contemporaries, Boskovich’s continual self-representation ran counter to the adoption of a collective political subject by many of his peers, for example the artists Félix González-Torres, Barbara Kruger, and Louise Lawler, and the collectives Group Material (of which González-Torres was a member) and Gran Fury (the art and propaganda arm of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power [ACT UP]). Rather than finding a place for his artwork within the public political struggle, Boskovich withdrew his practice into his home. Against the current necessity of being activated politically by grief’s implication of the self in the other, Boskovich’s artworks insist that grief is an alienating wound.

In 1995, AIDS killed Boskovich’s boyfriend, Stephen Earabino, at the age of thirty-two. A year after Earabino’s death, John Boskovich moved into 335 N. Orange Drive, a house in the Fairfax district of Los Angeles, and created Boskovich Studio (“Boskostudio”). There he designed thematic rooms based on personal symbology. These included the Millennial Hallway, the Sandra Bernhard Recuperation Laundry Room, and the Psycho Salon, the house’s living room. He decorated the rooms with ornamental sculptures, light fixtures and wall works that he fabricated, and artworks he had previously shown in galleries. Boskovich viewed the entire project as a happening confined to his private life. In his gallery exhibitions, Boskovich allegorized his own alienation by representing himself with inscrutable signifiers from his personal life. Boskostudio allowed Boskovich to embrace solipsistic self-enclosure by making himself his works’ primary audience. There was no need to signify or communicate the self to anyone who was not already personally intimate with the artist. After one last solo exhibition (with Felsen in 1999), he stopped showing in galleries altogether.

Boskovich died in 2006. His cousin and closest survivor, Krista Montagna, packed up his things, and they remained in storage for over a decade. In 2019, O-Town House founder and curator Scott Cameron Weaver worked in consultation with Montagna to recover the contents of Boskostudio and exhibit them as Psycho Salon. The back gallery recreated the artist’s Psycho Salon. The gallery’s front and upstairs rooms displayed a survey of the artist’s image/text works in a manner that imitated the artist’s treatment of artworks in his own home.

Psycho Salon, installation view, O-Town House, Los Angeles, September 27, 2019–January 4, 2020. Courtesy of the John Boskovich Estate and O-Town House, Los Angeles. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.

In presenting the works that formerly occupied Boskostudio (some of which had never been exhibited publicly), Weaver faced a dilemma: How do you frame a public exhibition of works that the artist completed by displaying them in private? The Psycho Salon, as recreated at O-Town House, elaborated a personal symbology around key aspects of Boskovich’s life: his fraught passion for controlled substances, his pantheism, and his love of authors T. S. Eliot and Jean Genet. A rug with a pentagram design covered the floor. Color Correction Series/AA Bumper Stickers (1997), vibrant paintings of Alcoholics Anonymous mantras such as “Powerless,” lined the room’s fireplace (represented at O-Town House by a vinyl wall-graphic). The series calls to mind Ed Ruscha’s meditations on graphic design that wrested text from its chain of signification, indulging in its semiotic and textural excess. Above the “fireplace,” a convex security mirror condensed the surrounding room into a two-dimensional image, a diagram of the many voices that once spoke in Boskovich’s head. Three Krishna figurine lamps, Hare Krishna Lamps (1997), peered into the room from their polygonal Formica bases, onto which Boskovich had affixed passages from T. S. Eliot. The quotes on the lamps, from “The Dry Salvages,” the third of Eliot’s Four Quartets (1941), model the fragmentation at play in the room. One reads:

I sometimes wonder if that is what

Krishna meant—

Among other things—or one way

of putting the same thing:

That the future is a faded song,

a Royal Rose or a lavender spray

Of wistful regret for those who are

not yet here to regret,

Pressed between yellow leaves of

a book that has never been opened.

And the way up is the way down, the

way forward is the way back.

Even in pieces such as Hare Krishna Lamps, which were specifically designed for Boskostudio rather than gallery exhibition, Boskovich worked in a mode of sculptural assemblage familiar in contemporary art. In a 1997 account of a visit to Boskostudio published in Interior Design, David Rimanelli, a critic and personal friend of the artist, compared Boskostudio to a text-heavy art exhibition. Imagining the response of a begrudging text-art viewer, Rimanelli wrote: “I don’t go to the gallery to read, these people would say. So imagine going over to someone’s house to read.”1 Ironically, it is the very fact that the objects once inhabiting the artist’s home resemble late conceptual art that excludes them from categorization as domestic ready-mades. Boskovich’s use of art’s vernaculars alongside religious and pop-cultural motifs suggests that art is yet another personal predilection expressed in his customized personal effects.

Psycho Salon, installation view, O-Town House, Los Angeles, September 27, 2019–January 4, 2020. Courtesy of the John Boskovich Estate and O-Town House, Los Angeles. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.

The O-Town House gallery occupies one suite in architect Franklin Harper’s Granada Buildings, a historical Spanish Colonial Revival complex built in 1927 as live/work spaces. While the apartment is typically dressed as a gallery, evenly lit and painted white, the Psycho Salon exhibition amplified the space’s homelike qualities. The Boskostudio Psycho Salon living room’s avocado green wall paint was applied in all of the gallery’s rooms. Curtains and custom light fixtures from Boskostudio gave the show crepuscular lighting. Works were integrated into the gallery’s domestic architecture. The front room gallery desk featured a selection of decorative flasks and beakers from Boskostudio as well as objects fabricated and titled by Boskovich (some for gallery exhibition, some not). One had to sneak behind the desk, past Weaver and his open laptop, to get a look at Untitled (“Index” Lightbox) (1998) from the Sandra Bernhard Recuperation Laundry Room, an illuminated reproduction of the index of Camille Paglia’s Vamps and Tramps: New Essays, in which Boskovich is listed.

Boskostudio’s Psycho Salon living room served as a metonym for the whole exhibition. With Weaver as its host, the exhibition invited viewers to make themselves at home among the artist’s former possessions. It is therefore tempting to write about the show at O-Town House from within a fantasy of identification with Boskovich, as if slipping into the artist’s shoes. But it is crucial to remember that Boskovich never attempted to dress up a gallery as a domestic space, and his early work deliberately addressed the separation between the artwork on display in a gallery and the artist’s private life.

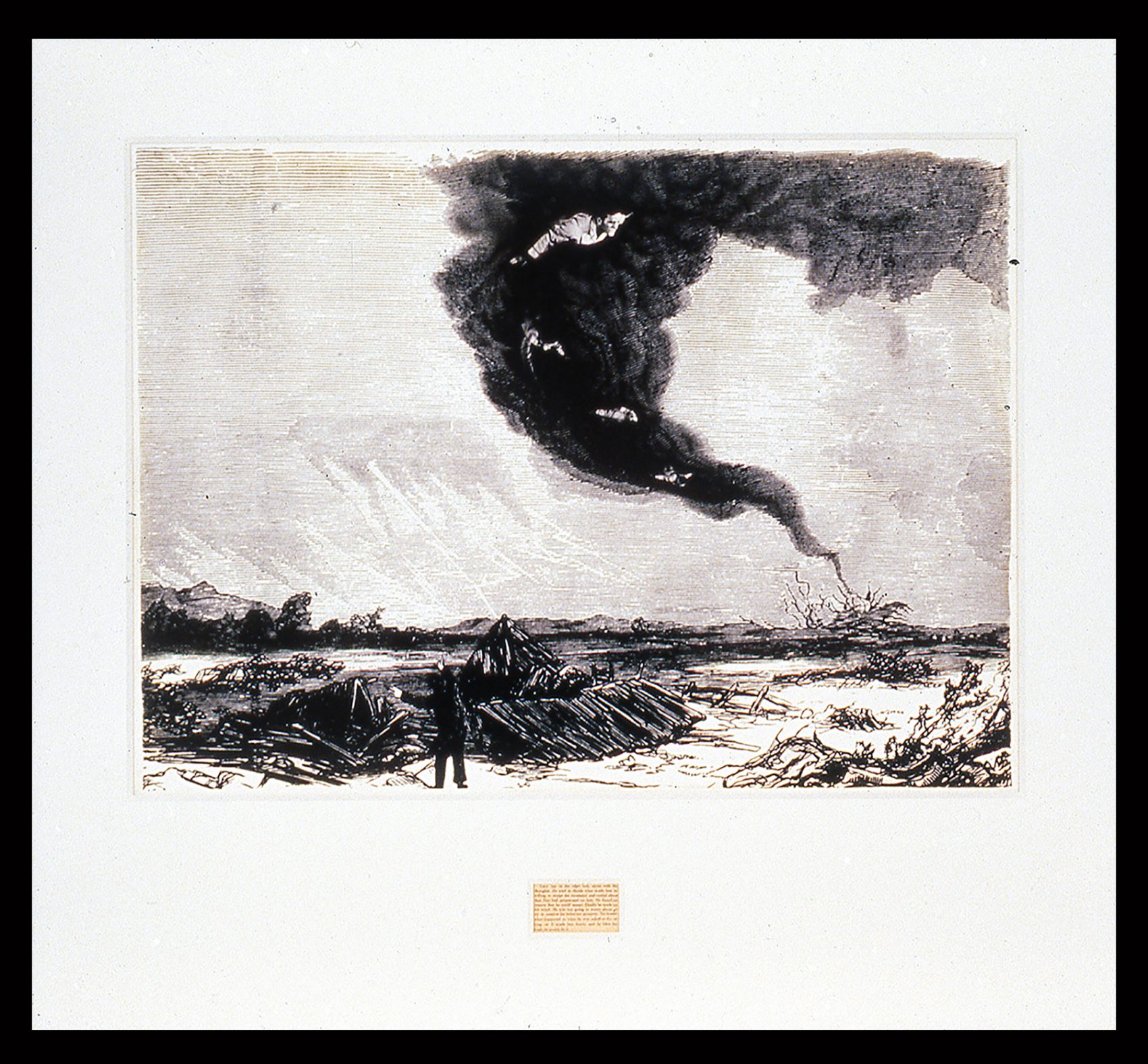

Boskovich’s gallery works emphasize the distance between the fictional construction of identity inherent in any artwork and the artist’s biography. For example, Self-Portrait (1987), a photomontage included in the exhibition at O-Town House, combines a found etching with a photograph of Boskovich. The etching depicts a man standing before the remnants of a ravaged house, watching a twister destroy another structure on the horizon. Boskovich’s likeness rises cartoonishly in the funneling cloud. A text clipping, apparently plucked from a paperback novel and inserted into the mat below the photomontage, captions the image. It describes the protagonist’s rumination over his compulsive return to a sadistic partner, ending with a vow to follow his desires without questioning them, so long as they “get him off.” The work’s title and the text’s description of a subject caught in a moment of self-reflection suggest that both of the men pictured are Boskovich: the artist encounters his own image.

John Boskovich, Self Portrait, 1987. Gelatin silver print, gouache, clipping from paperback novel, 42 × 46 in. Courtesy of the John Boskovich Estate and O-Town House, Los Angeles.

The pictorial structure of Self-Portrait participates in the appropriation discourse of Boskovich’s moment, and also calls up now-common meme formats in which text diagrams and dramatizes an image—for instance the formula “Me: . . . Also Me: . . . ” Yet Boskovich’s insistence on retaining personal traces separated him from a tendency of the avant-garde of his time, which was increasingly speaking through mass culture’s conventional forms. Compare Self-Portrait to Barbara Kruger’s You Are Not Yourself (1981), which typeset its titular slogan in Oblique Futura over a single graphic image of a woman contemplating her reflection in a bullet-shattered mirror. The address of You Are Not Yourself is as disembodied as the advertisements it mimes. In contrast, Boskovich’s beveled mat more closely resembles a collage-style family portrait.

Perhaps it was such traces of “taste” and the “artist’s hand” that drew critic Suzanne Muchnic to speculate about Boskovich digging for the material in antique stores and the local paper.2 Self-Portrait harks back to works of Dada, COBRA, and the surrealists, for example Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q (1919), in which artists used framing devices and handwriting in the work as the wink of the clever artist. If the massifying vernaculars of artists and collectives (Kruger, Group Material, and Gran Fury) that channeled resources and efforts from the art world into public political discourses and actions were avant-garde, Boskovich’s domestic “wink” is kitsch: an irredeemable rehashing of the past in a non-original mode belonging to the other end of cultural production.

Boskovich’s Self Portrait Sculpture–Honey Bear (1993) quarantines a single bear-shaped bottle, half full of honey, in a plexiglass vitrine. The bear’s reserve supply can be read as a metaphor for resources, both economic and energetic. An inheritance funded by his family’s commercial agricultural operation, Boskovich Farms, afforded the artist space and time to pour into his work without requiring him to prove its value on the market. Producing work away from the market that raises a work’s economic value and thus its likelihood of preservation, Boskovich must have been aware of his work’s finitude. The protective vitrine, physically bound to the artwork, is itself plastic—an ephemeral material that conservators struggle to preserve.

Psycho Salon, installation view, O-Town House, Los Angeles, September 27, 2019–January 4, 2020. Courtesy of the John Boskovich Estate and O-Town House, Los Angeles. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.

It is useful to compare Self Portrait Sculpture–Honey Bear to González-Torres’s Untitled (Portrait of Ross) (1991), which also represents mortality using a sweet, mass-produced food product. Untitled (Portrait of Ross)’s mound of candies begins its life at the healthy bodyweight of González-Torres’s late partner, Ross Laycock. As gallery and museum visitors take pieces of candy, the pile gradually diminishes, analogizing Ross’s wasting away from AIDS. In their participation, museum goers are implicated in an ambivalent allegory for both collective negligence and public mourning. Where Self Portrait Sculpture–Honey Bear preserves, however tenuously, an individual unit of the massproduced object, Untitled (Portrait of Ross) is defined according to a conceptual contract between the artist and the collector, through which “Ross” is eternally reborn as an ephemeral treat in the displays of institutional collections around the world.

At O-Town House, Self Portrait Sculpture–Honey Bear was presented at the rear end of the gallery desk, below and self-isolated from a collective of anonymous, beautiful, and dead (sprayed clean of honey) bears illuminated from beneath by black light. Boskovich assembled the glowing purple bear light fixture, once installed in Boskostudio’s meditation room, from the honey bear bottles used in The Honey Machine: It Works Without Thinking (1993). Presented in his 1993 exhibition Rude Awakening at Rosamund Felsen, The Honey Machine alternated 125 full honey bears and 125 gold Buddhas in five identical plexiglass cases. The number of figurines derived from Boskovich’s observation that there were 250 personals placed in every issue of Frontiers, a gay men’s magazine in Southern California.3 If the bears (and Buddhas) in The Honey Machine were stand-ins for men populating the Frontiers’ classifieds, the ultraviolet light installation was their afterlife. While honey-bear-Boskovich and the anonymous hookup bears were pressed from the same mold, the vitrine temporarily preserves Boskovich-bear as the individual artist marked by individual imperfections: honey encrusts his tip, and his price tag will never be removed.

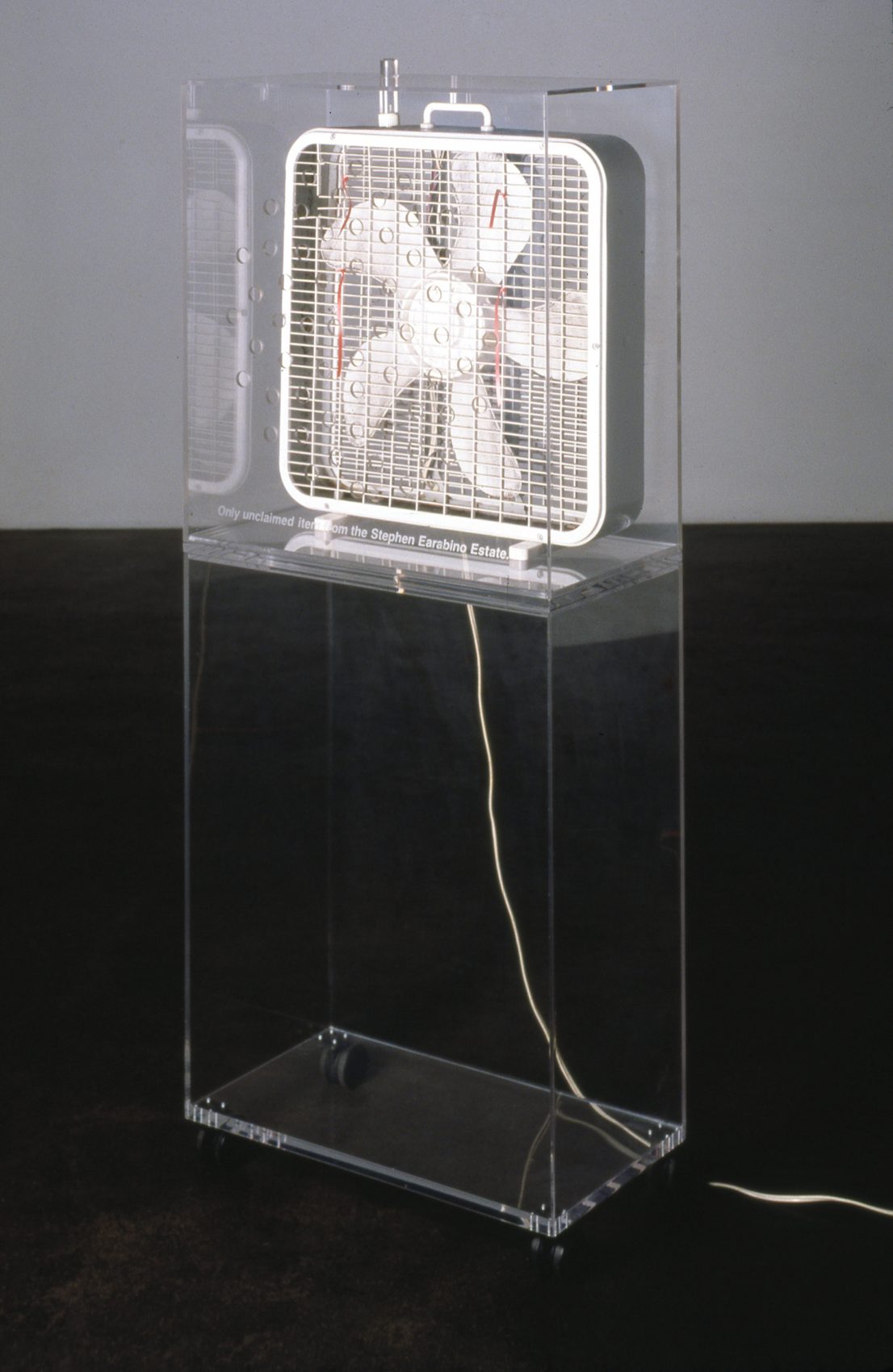

In memory of Earabino’s death, Boskovich donated a handful of his own works to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Among the works donated is Electric Fan (Feel It Motherfuckers): Only Unclaimed Item from the Stephen Earabino Estate (1997). Feel It Motherfuckers encases a common box fan, which the title tells us was the only object left after others had had their pick, in a customized vitrine. Holes punched into the plexiglass in a concentric pattern imply that the fan can be turned on and off. But what “It” would “Motherfuckers” feel if the fan were to blow on their faces? Is “It” how Earabino felt when he was alive, comforted by his fan? Or is “It” the burn of grief, which no viewer would choose to feel of their own will in the same way one would choose, say, to taste the sweetness of a piece of candy. Whereas González-Torres’s works suggest that grief can be felt collectively through participatory actions, Boskovich’s works imply that such participation is inadequate in communicating the experience of grief.

John Boskovich, Electric Fan (Feel it Motherfuckers): Only Unclaimed Item from the Stephen Earabino Estate, 1997. Electric fan encased in plexiglass with vinyl faux etching, plexiglass base with casters, 56 7/8 × 22 3⁄4 × 12 1⁄2 in. Collection MOCA, Los Angeles. Image courtesy of the John Boskovich Estate and O-Town House, Los Angeles.

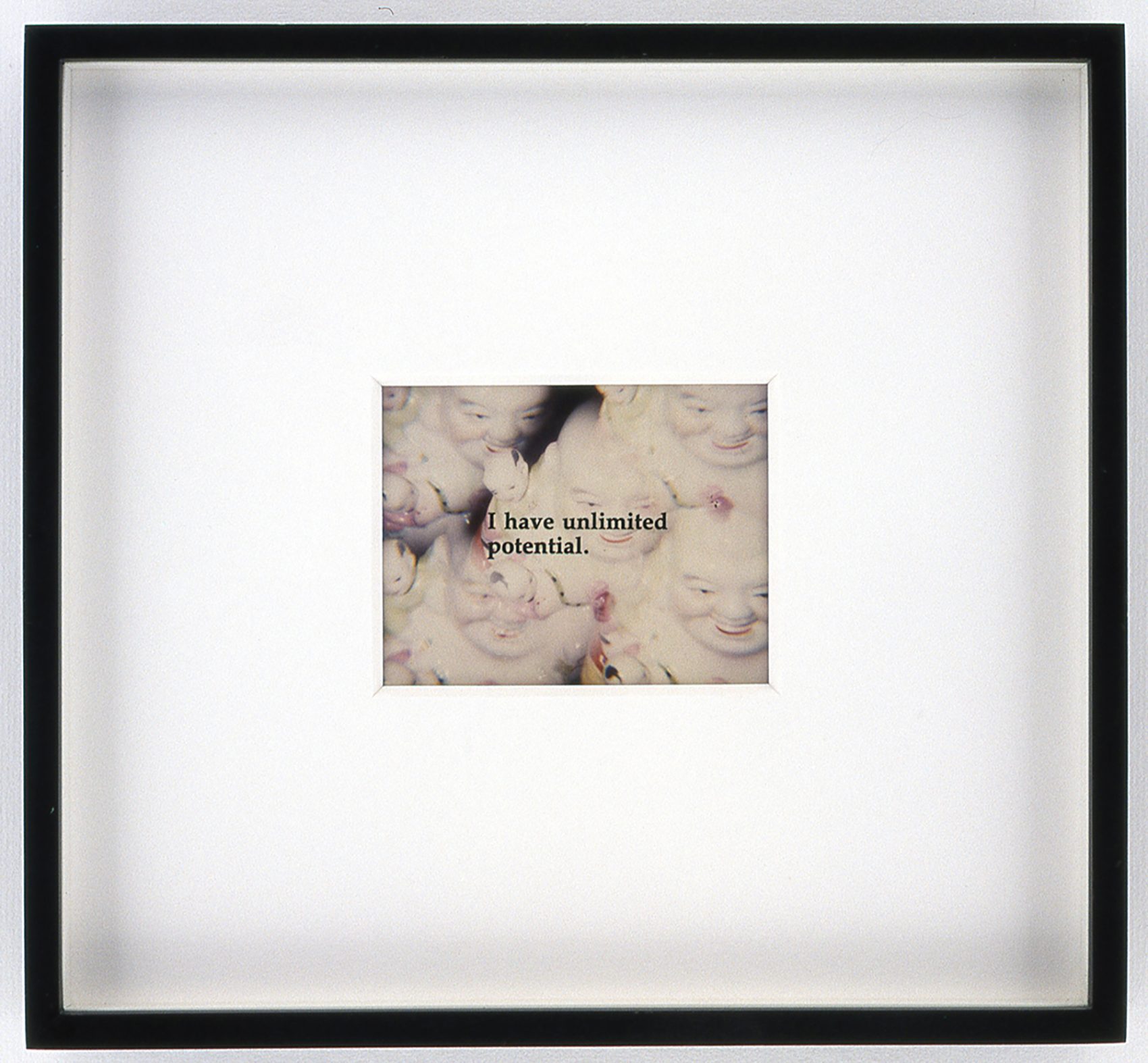

Like Earabino’s fan in Feel It Motherfuckers, the Rude Awakening Series (1993–97) presents objects that prevent viewers from projecting themselves into fantasies of identification with Boskovich. The image/text works, hung salon-style in the hallway at O-Town House, were produced during the period in which Earabino died and Boskovich moved to 336 N. Orange Drive. While this period was rife with what Boskovich described as “drama flourishing abundantly,” the personal references in the images are coded and obscure.4 Each work in the series is an individually framed Polaroid (or set of Polaroids) with a caption silkscreened onto the mat or over the image. Most of the texts repeat aphorisms from Joyce Strum’s book Love Lines: Affirmations for Mind, Body, Spirit (1987), a self-help bestseller of the era. Boskovich began working in this format after seeing a friend receive a copy of the book as a hospice gift. According to the artist, the work in the series was intended as a polemic against dogmatic adherence to the self-help ideologies he was seeing proffered as a strategy for coping with the “rude awakening” of AIDS.5 The pieces’ titles, which differ from their silkscreened captions, offer another level of metadata: they tell when and where the photos were taken or suggest an inside joke. For example, “Oración de la Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe,” Another Angle of Stephen’s Day of the Dead Altar November 1995 (1997) is a photograph of a janky stovetop altar bearing the caption “I acknowledge my personal power.” In the hazy photograph, one can make out a cane resting on a Virgin Mary T-shirt that has been tacked to the oven, indistinguishable shiny red objects on a round platter, and empty honey bear bottles tied up over the stove’s burners. One might ask what personal power is acknowledged in Boskovich’s obscure memorialization of his recently deceased boyfriend. Is it the sadist’s power in tying up the bears? Or the mystic’s in communing with the dead? One can’t be sure.

The Polaroids index the lack in the real—the distance between what the camera reveals and the aspirational images that the Love Lines affirmations conjure. Rude Awakening Series: Lurking, in Seclusion (After Rehab) (1997) places “I am successful and prosperous” below a blurry image of a honey bear. The pairing of the two phrases—in the subtitle and the caption—may not be entirely ironic: rehab may very well have been a success. And yet a bear “lurking in seclusion” is hardly an affirmative image. See also Rude Awakening Series: Urban Protector . . . Not, “Tony Cartulli’s cock” Summer 1996 (1997) (caption: “I have a limitless capacity for joy”), in which the camera points down stupidly at what is presumably Tony’s dick, leaving it unclear by what fantasy “joy” is produced, if at all. In Rude Awakening Series: If It Works Don’t Fix it (TV Shots), timestamps take the place of texts below Polaroid “stills” of Valley of the Dolls, suggesting time carrying on through repetition. A small Buddha appears in I, Tina (1997), calling up associations, for those familiar with drugs’ street names, with weed (Buddha) and crystal meth (Tina). When the Buddha trinket reappears in the series, it cues viewers that someone is getting high out of frame—far away from the clear narrative of progress affirmed in self-help.

John Boskovich, I, Tina, 1997. Polaroid photo, silkscreen, 9 1/8 × 9 7/8 in. Courtesy of the John Boskovich Estate and O-Town House, Los Angeles.

Boskovich emphasized the impermanence of Boskostudio, insisting that “the documentation exists only in the still photography of Toshi Yoshimi and in my memory and those that live, work, and play there. . . .” Yoshimi’s images, published in Interior Design to accompany Rimanelli’s account, show the house as a set, empty of people. No traces remain of anything that might have transpired the night before the shoot. According to the artist, Boskostudio was not in the “genre of Installation Art” but rather “akin to something like a John Cage or a Fluxus performance where there is a non-narrative structure with a beginning and an endpoint.”6 Boskovich’s domestic life became the artwork. Objects once treated as gallery art were only included in Boskostudio insofar as the artist chose to live with them. Whereas many happenings or works of Cage and Fluxus are conceptually defined by a score for others to follow, Boskostudio’s parameters end with the whims of Boskovich himself. Boskovich’s death was the happening’s final event. Boskostudio can never be recreated.

Nilo Goldfarb is currently based in Los Angeles.