A strange dichotomy persists, an opposition between “craft” and “conceptual” art practices, as if the handmade quality of handcrafted objects somehow drains them of meaning and ideas, as if an emphasis on “process” would negate the possibility of complexity and contradiction. Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reefs explodes this preconception, presenting handicraft as a place and (more importantly) a time for thinking—about mathematics, about color, texture, and form, about ecology and climate change, about community and women’s experience, and about art.

Historically, the classic types of women’s handwork, such as knitting, quilting, crochet, weaving, became hobbies when mass production provided cheaper versions of the sweaters, socks, quilts, and other useful items previously made at home. As hobbies, specifically women’s hobbies, these practices were culturally disparaged, valued only within an almost secret society of practitioners, that is, experienced crafters who could assess and appreciate workmanship, innovation, and aesthetic choices. Nevertheless, within the context of contemporary art, another kind of conversation took place, a conversation which reconsidered the “wasted” time given over to repetitive gesture, to produce a more-or-less unnecessary object; a conversation that recognized this special kind of time as unfolding outside the system of exchange that structures and values our lives. Theories of the gift as a moment of excess which exposes the narrow parameters of the exchange economy can even salvage the (possibly ghastly) sweater your grandmother knits for you every other year, retrieving such ordinary objects for cultural criticism. The value of the hand-knitted sweater lies in the unnecessary and excessive pleasure experienced in the making of it, as well as the disruptive and inexplicable gesture of the gift. As an object signifying both kinds of excess, it testifies to the hours withdrawn from the exchange economy, the maker’s pleasure woven into every stitch. Ultimately, the homemade object represents unmeasured time invested in its making, and I would argue, the mental space which that time may open up.

In other words, the notion that (conceptual) thinking necessarily precedes (hands on) fabrication is a preconception that this show challenges with precision and force. I propose that any consideration of handwork, fancywork, women’s work, or indeed any practice which falls under the heading of what might be called “Michael’s culture” (in homage to the chain of gigantic craft stores known as “Michael’s”), any consideration of these hobbies (and art practices) requires a re-evaluation of reverie, as a particular kind of mental state allowing certain kinds of imaginative thought to emerge, which a more focused, conscientious thinking may suppress. My dictionary defines reverie as “an act or state of absent-minded daydreaming,” and gives its etymology as deriving from Old French resverie meaning “wildness,” from resver, to behave wildly, or to wander; it concludes: “see RAVE.” Reverie, therefore, is a raving, a wild wandering of the mind, where unexpected thoughts and images can jostle each other, memories can momentarily replace present reality, dreams can be remembered in fragments of color and light. Valuing this kind of mental experience is a characteristic move of feminist thinking, which looks again at the disparaged and the overlooked, especially those experiences specific to the isolation of domestic space, to reconsider their possible meanings and agency.

That reverie and mathematics should go together is one of the thrilling paradoxes of the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reefs project. The origins of the project lie in a personal investigation (by twins Margaret and Christine Wertheim) into the models of hyperbolic geometry originally constructed in crochet in the 1990s by Daina Taimina, a Latvian mathematician working at Cornell. I won’t attempt to give a history of hyperbolic geometry; instead, I refer the reader to Margaret Wertheim’s small book, A Field Guide to Hyperbolic Space: An Exploration of the Intersection of Higher Geometry and Feminine Handicraft (2007), published by the Institute for Figuring, an organization created by the Wertheim sisters and responsible for the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reefs exhibition, and other projects which hover on the boundaries of art and science. If geometry is the mathematics of flat and spherical surfaces, hyperbolic geometry is the math of a surface not unlike a sphere turned inside out, in which the meridians curve outwards (as opposed to curving inwards, as spheres do). It is also the bio-logic of many different organic life forms, for example, various undersea creatures that use their large surface area to absorb nutrients from the sea. Hyperbolic form is familiar to us from the structure of a lettuce leaf, crenulated and frilled, yet mathematicians were blind to the many examples of hyperbolic structures in nature. Indeed, until Taimina made her breathtaking conceptual leap, no one had ever successfully produced an actual model of hyperbolic space. If you can imagine people doing math about spheres, without having an actual sphere to handle and observe, and then one day someone appears with a beach ball, you get a sense of the impact of Taimina’s crochet models.

The Institute for Figuring, Toxic Reef, 2008. Installation at the Hayward Gallery, London. Blue plastic anemones by Clare O’Callaghan made from New York Times plastic bags embellished with ring-pull tops and plastic drinking straws. Courtesy Track 16 Gallery, Santa Monica. Photo by Margaret Wertheim. © The Institute for Figuring.

In December 2005, contemplating a bunch of crocheted geometric models scattered across their coffee table, Christine remarked to Margaret: “It looks like a coral reef.” The next thought was inevitable: “We could crochet a coral reef.” Never expecting more than perhaps a dozen people to join them in this quixotic endeavor, the sisters posted an invitation on the IFF website, and since then, hundreds of women—participation is 99.9% women—in many different countries have contributed to the project, with undiminishing enthusiasm.

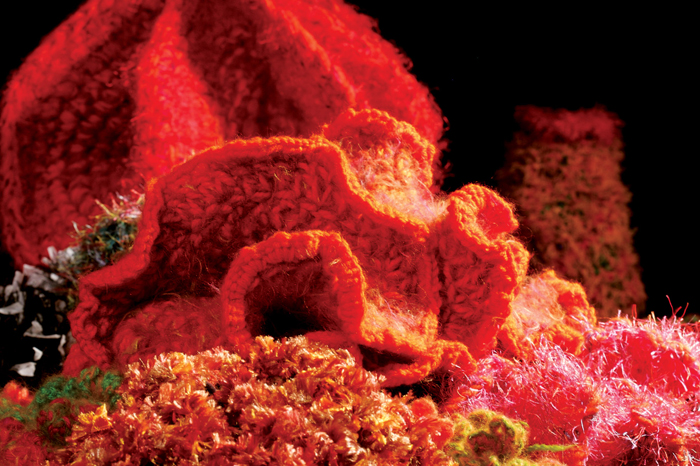

The instructions are very simple: begin with a line of chain stitches, and then, after the initial row, increase every nth stitch, i.e. every 6 stitches, or every 3 stitches, etc. Given this formula, women who were experienced in crochet and women who had never picked up a hook threw themselves into the exciting process of constructing hyperbolic undersea forms in crochet. The diversity of these forms is partly due to the wide range of materials used, including string, fuzzy wool, delicate thread, bright orange synthetic yarn, silver wire, and plastic bags cut into lengths and crocheted. It was quickly discovered that irregular increases in stitches produced more organic shapes, and it is the sheer inventiveness and tremendous variety of forms that gives such energy to the installed Reefs.

The Institute for Figuring, The People’s Reef (A Melding of the Chicago Reed and New York Reef), 2007-08. Aerial view. By the Chicago Reef and New York Reef contributors. Courtesy Track 16 Gallery, Santa Monica, Photo by Sean Meredith. © The Institute for Figuring.

Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reefs consists of elements put together in an almost infinitely re-arrangeable form. The flexible backbone of the mathematics provides an internal consistency across diverse and disparate participants and materials, allowing multiple individual contributions to be combined into a larger whole—the Reefs themselves. Yet there is no standard to maintain or deviate from; each instance of hyperbolic crochet invents itself, opening up room for experiment and imagination that is evident in the indescribable diversity of color, texture and form. The combination of many parts into a larger whole is itself a materialization of the virtual community of women participants, mostly working in splendid isolation. Often the individual corals, sea slugs, sea urchins and underwater anemones are small, light, and easily mailed to the Institute, to be placed in combination with many others, sent in by other crocheters, who may never meet.

This mental shift in scale (from individual item to larger combination) is mirrored by the relation of the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reefs to their real-world counterparts, particularly the Great Barrier Reef in the Pacific. From the familiar stitch, fingered by the individual artist, to the unimaginable vastness of the ocean—such is the reach of this project, as it invokes concerns about global climate change and pollution. The world’s coral reefs serve as the canary in the coal-mine, alarming us, since a change in the ocean’s temperature of one or two degrees will destroy them. An urgent and ongoing concern with the negative impacts of plastic and its almost indestructible persistence, especially in the ocean, pours into the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reefs, with many participants recycling plastic materials (such as blue New York Times delivery bags, or metallic video tape) to make undersea forms. One corner of the gallery supports The Midden, consisting of all the plastic that entered the home of Christine and Margaret Wertheim over a two-year period. Part of the impact of the show is straightforward consciousness raising, specifically about coral reefs, plastic, and the future of the oceans. Workshops invite people to think about these questions in greater depth, while learning to crochet hyperbolic forms out of plastic bags. Grounded in higher geometry, which invites the viewer to imagine another kind of space, even to consider our universe as hyperbolic in structure, at the very same time this work reaches out towards community politics. The multiple workshops in different cities have inspired women to make their own crochet reefs in London, Sydney, Latvia, New York, and Chicago.

The Institute for Figuring, Crochet Reef, 2007. Courtesy Track 16 Gallery, Santa Monica. Photo by Alyssa Gorelick. © The Institute for Figuring.

It seems as if another kind of artist is proposed by this collaborative work, an implied artist whose energy and invention are countered by the sheer repetition of stitches, the conglomeration of hours and hours of time. This artist is thrilled at the invitation to crochet something useless—not another baby blanket, not another hat—and to give away her creation to join in something big, something with reach and meaning. While she may have confidence in her expertise, her work avoids grandiosity, remaining at a manageable scale (until it joins the larger combination). This artist particularly enjoys the invitation to sink below the ocean, to enter its dreamlike darkness, an alternate reality of color and shape. She enjoys making phallic shapes, using her hook and yarn to build leaning towers, star shaped fortresses, a landscape drawn in lumps of color. She enjoys making vaginal shapes, fuzzy, curly edged openings, soft to the touch, fronded and weird. She sinks into reverie, doing almost nothing, watching TV maybe, repetitively moving her fingers over the shape as it slowly emerges, revealing itself in its simplicity and complexity. In this reverie is the potential for transformation, though it may also be the last resort of the despairing. Perhaps she derives comfort from working in such a whimsical way: there is no right or wrong way to do it, rather a set of parameters that offer innumerable possibilities. Comfort is no small thing; it should never be dismissed.

The Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reefs project invites us to reconsider the meaning of self-chosen repetitive tasks, the place of fantasy in everyday life, the value of boredom as a space for reverie, and the potential for change evidenced by the extraordinary response of many different women who wished to participate in this artwork. In The Tempest, Shakespeare proposes the sea as the site of transformation and renewal:

Full fathom five thy father lies; Of his bones are coral made: Those are pearls that were his eyes: Nothing of him that doth fade But doth suffer a sea-change Into something rich and strange.

Pulling in different directions, the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reefs point us towards mathematics, towards a consideration of collaboration, towards eco-consciousness and action. Most of all, they draw us into the space of reverie, as we join the multiple artists in a slowed down time and space, looking carefully, with a sense of wonder, at the infinitely varied forms and their combination. If the undersea realm is for us an alternate reality, then its utopian potential is here most poignantly proposed.

Leslie Dick is a writer who lives with her daughter Audrey in Los Angeles. She teaches at CalArts.