Meret Oppenheim and unnamed collaborators, L’ancêtre de la sirene, circa 1970s–80s. Colored pencil and felt pen on paper, 11 3/8 × 7 7/8 in. Courtesy of Karma International.

In 2012, a cache of cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse) drawings by Meret Oppenheim and unnamed collaborators was found in a drawer in the family home by a niece, many years after Oppenheim’s death. Their exhibition for the first time, at Karma International in Los Angeles, prompts us to consider the artist’s precise relationship to surrealism and urges a reconsideration of her work at large. The drawings were made from the 1970s to the 1980s, at least ten years after Oppenheim officially removed herself from the surrealist group in 1960. Also, significantly, they were made after Breton’s death, in 1966, and the dismantling of the Paris surrealist group in 1969. Perhaps the final collapse of Breton’s circle provided an opening for Oppenheim to nurture her innate surrealist spirit, so present in her early life and work?

Fame, for Oppenheim, is a fur teacup. Object (1936) was a cup, saucer, and spoon that she purchased at the French department store Monoprix and clothed in Chinese gazelle fur. The work was spawned from a joking retort to Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso, and it quickly became the surrealist object par excellence.1 In 1936, Oppenheim was at a Parisian café with Pablo Picasso and his lover Dora Maar. Picasso and Maar were admiring Oppenheim’s fur-covered bracelet, which she was selling to the fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli. As the story goes, upon seeing the bracelet, Picasso joked that you could cover almost anything in fur. Oppenheim retorted, “Even this cup and saucer.” When her cup was empty, she continued calling out to the waiter: “Waiter, a little more fur.”

First exhibited by André Breton as part of the Exposition surréaliste d’objets in 1936 at Galerie Charles Ratton, Object was initially titled matter of factly, Tasse, soucoupe et cuillère revêtus de fourrure (Cup, Saucer, and Spoon, Covered with Fur) by Oppenheim.But Breton famously retitled the work as Le Déjeuner en fourrure (Breakfast in Furs), stamping its future with a farmore libidinal interpretation.2 Ten years later, it would be the Museum of Modern Art, New York’s first acquisition of an artwork made by a woman.

The title Breton gave Object—Breakfast in Furs—is exemplary of a “collaborative” intervention typical of surrealism, but it has produced a distortion in Oppenheim’s legacy of overt sexual and fetishized overtones she did not initiate on her own. Such repeated objectifying and detaching of the female creator from her work—as if a sacrificial femme-enfant or muse—led Oppenheim to cut ties with the organized movement more than once. Nevertheless, the modes, drives, and attitudes of surrealism are evident throughout Oppenheim’s oeuvre, in her preoccupation with dreams, her engagement in the realms of the unconscious, and her later participation in surrealist games, such as the cadavre exquis.

In Bice Curiger’s monograph and catalogue raisonné on the artist, Oppenheim ruminates on her later experience with the cadavre exquis and explains how the game is played. She clearly explains and denies the game’s exclusive association with surrealism, instead describing it as “an old children’s drawing game”:

In August 1971, Anna Boetti and Roberto Lupo, both from Turin, and I played an old children’s drawing game. Each player draws a head (or anything that counts as the top of a figure) on a piece of paper, folds it back so that only the two lines of the neck are showing, and passes it on to the next person. Then everyone adds a torso, folds the paper and passes it on again. Finally the players add feet or a base of some kind. Then the pictures are unfolded, but white side up so the drawing is not visible. To give the picture a title, everyone writes an adjective, folds over the paper, passes it on, writes a noun or a name on the next sheet and a verb on the third. Then the players read the titles and look at the drawings.

The Parisian Surrealists named this game after a title that had once been invented while playing: Le cadavre exquis (“Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau—The exquisite corpse will drink the new wine”).3

Meret Oppenheim, Pair of Gloves with Veins, 1985. Goat suede with silk-screen and hand-stitched veins, 5 5/8 x 3 2/4 in. Included in a limited edition of Parkett issue 4, ed. 150/XII, signed and numbered. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ProLitteris, Zurich.

The cadavre exquis collides the impossible with the illogical. It condenses a singular sense of wholeness and narrative from a condition of plurality. The distinction made by Oppenheim is telling, as is her intention to, consciously or unconsciously, overwrite the surrealist claim to the game with a related but preexisting concept: a return to childhood. The difference between a surrealist game and a child’s game reveals the distinguishing lineage of a surrealist spirit that is devoid of one specific historiography or grouping and spans a more universal approach accessible to the many. That leads me to consider her works outside of a strictly surrealist approach.4

In these twenty-six cadavre exquis drawings, a ferality is unleashed with humor, a spiritual mythos, and a cosmic striving for sexual liberation fit for the goddess of Gaia. Animals, fashion objects, monsters, humans, goddess, and genitalia become equalized within the segmented structure. In Righe (Lines, circa 1970s–80s), a Christ-like head is accompanied by a three-headed dragon scarf that readily blends into an alluring blue coat. The drawing’s torso also wears a coat with painted red outlines of hands, similar to Oppenheim’s Pair of Gloves with Veins, which she realized in 1985, the last year of her life, from an earlier sketchmade in the 1930s. Beneath the torso, the stubbly legs of a man in fancy cartoonish white dress shoes walk along a cobblestone street. In these collaborations, the contributions of both the trained draughtsman and the untrained hand are effortlessly connected in wonder and wholeness, revealing a mélange of imaginative creatures: some with heads, others with winged waists or clothing hangers as torsos, exaggerated breasts that become weapon-like and unruly, and copious depictions of pubic hair with equal scribbles of male and female genitalia. Most of the drawings are then titled, some in German, others in French; on occasion, a short English name, for example I don’t know! or The sky in the moon! (both works, circa 1970s–80s) or an Italian name such as Righe crops up. At times long and containing multiple languages, the titles provide an extra dimension to the poetics associated with the already wildly imaginative drawings. For example, the graphite drawing Vielleebchen, souverän, phantasieren, im Rotweinpiscine leider linkend (Many Loved, sovereign, to fantasize, in the Red wine pool, unfortunately linked) (circa 1970s–80s) depicts a wide-eyed female Cyclops with unruly patches of hair, or possibly breasts, stemming from the torso and descending into a skirt made up of numerous flaccid phalluses wrapped around the creature’s waist.

Meret Oppenheim and unnamed collaborators, Righe, circa 1970s–80s. Pencil on paper, 11 . Å~ 8 . in. Courtesy of Karma International.

The creators and the audience for these cadavre exquis were one and the same, even if the lived experiences of these evening parlor games cannot now be extracted from the resulting drawings. The creators, known (Oppenheim) and unknown (maybe Boetti and Lupo, and other participants lost to history) together, perhaps at the end of a comfortable dinner party, shared the sweet, unpretentious milk of play. These collective doodles were made sociably, unselfconsciously, and with no pretension to their eventual exhibition. The piecing together of segmented visions, mingles of conversation, and uninhibited lines became the evening’s digestif.

These cadavre exquis drawings were made toward the end of Oppenheim’s life. Why, one wonders, after leaving the surrealist movement did she return to a game so strongly associated with it? Was this an emancipation, a declaration that even if she dismissed the movement, the process for making these drawings was not exclusive to the surrealists? Did the official dismantling of the French group give Oppenheim an opportunity to reclaim the ideas and proclivities of a movement she had felt restrained by?

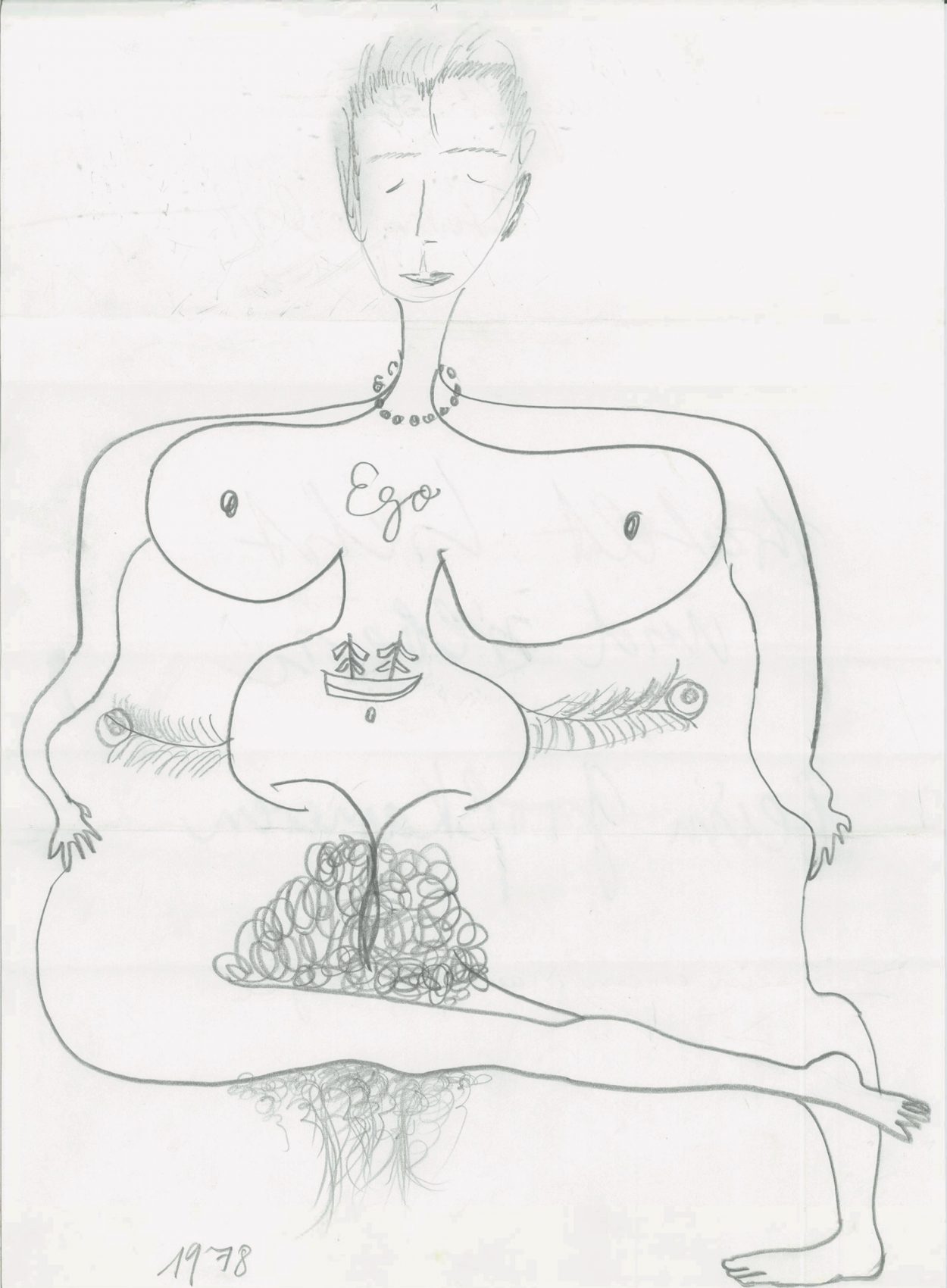

Lhlumpfi der Waldspecht strahlt Licht und silbern beim Grosskarieren in einem Maulwurfshügel (Lhlumpfi the Woodpecker shines light and silver in the grove of a molehill, 1978), resembles Oppenheim herself. The top section of the drawing crudely depicts a short-haired woman with chiseled bone structure, beady eyes, and a stern mouth. This Meret-ish head is carried on a thin neck adorned with a pearl necklace and the word “Ego” written in script between a pair of obtuse breasts. The work recalls the open-ended question who am I? that Breton first addresses in the beginning of his book Nadja. But who was Meret Oppenheim?

Born in 1913, Oppenheim’s story delineates the twentieth-century tribulations of a woman’s early fame and exemplifies her constant striving towards emancipation against a backdrop of war, avant-garde movements, and the conditions of fixed female gender assignment. From an early age, Oppenheim’s life parallels the surrealist movement. Her father was a friend to the mystical-leaning psychotherapist Carl Jung; learning of his theories at an early age, she began recording her dreams at 14. She was raised in a progressive cultural environment surrounded by various artists and writers, including Herman Hesse and the Dadaists, Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings. She spent her summers at Casa Costanza, a cherished family home in Carona, Switzerland, that continued to be a generative environment for Oppenheim throughout her life. She grew up playing games in Casa Costanza’s parlor room, and it is here that these drawings were tucked away in a drawer for almost four decades.5

Meret Oppenheim (left) playing Mah Jong with her grandmother and her siblings Kristin and Burkhard in the Casa Costanza’s parlour room, Carona, Switzerland, circa. 1926–27. Courtesy of Lisa Wenger, Carona.

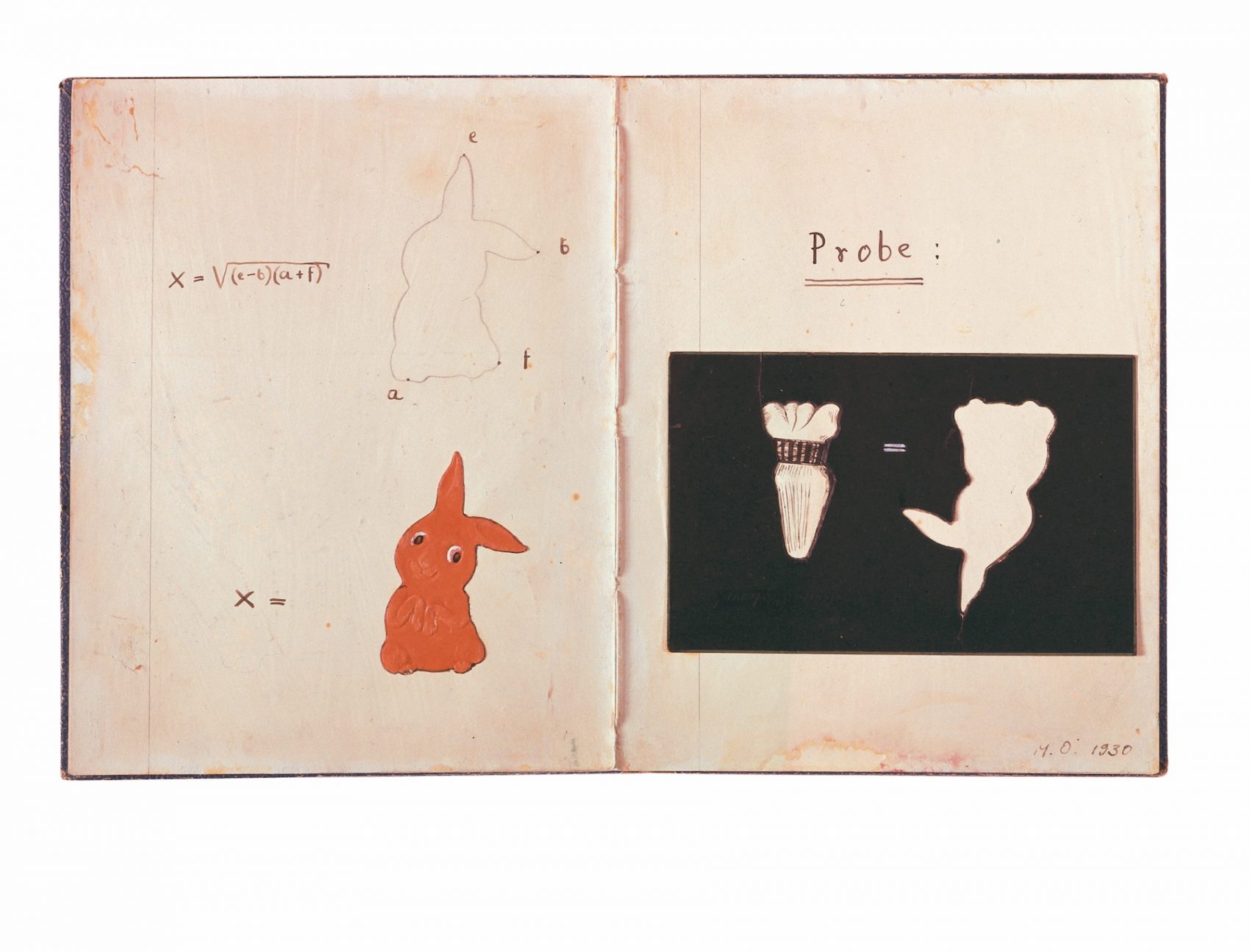

In Oppenheim’s first declaration as an artist, while still a school girl in Switzerland, she wrote “x = rabbit” and made a mathematical equation of the rabbit’s exterior points by measuring a representational drawing of a rabbit in her mathematics exercise notebook called Das Schulheft (The School Note Book, 1930).6 Two years later, at the age of eighteen, her father encouraged her to travel either to Paris or Munich to study art. Oppenheim chose Paris, the epicenter of the avant-garde, and left Switzerland with her companion, Irene Zurkinden, an older painter who acted as escort.7 The two women arrived in Paris in 1932 and immediately went to the popular artists’ hangout—Café du Dôme.

Surrealism had arrived eight years earlier, in 1924, as an organized movement under the initial theories and leadership of Breton. Their ideas built on the anarchic revolt of Dadaism against the stagnancy of bourgeois society—to them a major factor in the catastrophe of the First World War—and the new theories of the unconscious and dreams. As a leading avant-garde movement of its time, the surrealist group focused its interest in automatism by deploying a series of collective methods for art-making: international journals, automatic texts, incessant theorizing on the movement itself, new forms of poetry, and political actions. By the year 1929, the Paris surrealist group had splintered. Breton ousted some of the key early members, including the writers Philippe Soupault and Pierre Naville, for what he deemed disloyalty to the movement. The group took on a more overtly political and revolutionary agenda, attracting a younger, more international constituency. They made works collaboratively and with intention of revolution, for example the film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog, 1929), by Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel, and the journal Le Surréalisme au service de la revolution (Surrealism in Service of the Revolution, 1930–33), and they repurposed games like the cadavre exquis. These weaponized methodologies of pleasure, play, and the tapping into the unconscious were expressly intended to disrupt, challenge, and critique the comfortable status-quo of bourgeois life.

Meret Oppenheim and unnamed collaborators, Lhlumpfi der Waldspecht strahlt Licht und silbern beim Grosskarieren in einem Maulwurfshügel, 1978. Pencil on paper, 13 × 9 ½ in. Courtesy of Karma International.

Settling in Paris, Oppenheim took up residence in the Hotel Odessa in Montparnasse, which became her studio. She preferred working alone and only occasionally attended her studies at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière.8 With her strong personality, charm, and intellect, Oppenheim swiftly became both muse and artist in the movement. Hans Arp and Alberto Giacometti visited her studio, Breton was fond of her art and particularly liked the rabbit equation. She had a passionate albeit short-lived love affair with Max Ernst, and appeared in many of Man Ray’s photographs of the time, such as Self-portrait with Meret Oppenheim (1933) and Meret Oppenheim at the Printing Wheel (1933).9[[9]] Meret Oppenheim refused to see these photographs as collaborations, despite some critics in the past asserting such. In an interview with Robert Belton, conducted in 1984, Oppenheim clearly expresses that she saw Man Ray’s photographs of her as being solely his work: “Robert Belton: Speaking of androgyny, how do you feel about the photograph that Man Ray made of you? The one with the printing press handle mimicking a phallus. Meret Oppenheim: I don’t know. That was Man Ray’s work. RB: You don’t recognize this as your work in any way? MO: No, not at all. He was the boss.” Robert J. Belton, “Androgyny: Interview with Meret Oppenheim,” in Surrealism and Women, Mary Ann Caws and Rudolf Kuenzli, eds. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991), 70. Although young, she maintained her independence while simultaneously performing their idolized femme-enfant. She was given the nickname “fairy princess of the Surrealists.” 10

Meret Oppenheim, Das Schulheft (The School Note Book), 1930. Ink and collage on paper. 7 7/8 × 13 3/16 in. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ProLitteris, Zurich.

In the late 1930s, spurred by the onset of WWII, Oppenheim returned to Switzerland and kept up an intermittent, albeit ambivalent, contact with the surrealists in France. Object’s almost overnight fame outstripped her, and she fell into a personal and artistic crisis that lasted eighteen years. Although many accounts say otherwise, Oppenheim did continue to create and make work, but she often destroyed her output or left works unfinished. She was in a constant state of unease and agony over her creative output and its reception.11 It was not until 1954 that she was able to return to a renewed sense of the pleasure of making.12

Her final rupture with the surrealists came after the Exposition inteRnatiOnal du Surréalisme (EROS) in 1959. Breton asked her to recreate an intimate performance she had made in the spring of that year for a small circle of friends in her studio in Bern. Frühlingsfest (Spring Feast) was an elaborate banquet served—without silverware—on the body of a naked woman. Oppenheim conceived of the piece as an intimate celebration of seasonal abundance and the gifts of nature. Like Object, the work was spawned from a spontaneous conversation with friends, and she thought of it as an appreciation of the goddess and the primal creativity that arrives out of the ritual of dining with friends. However, as an unidentified female body (later replaced by a mannequin) lying naked on a banquet table in the context of EROS, it was criticized as another surrealist work that objectified women. In a later interview, Oppenheim spoke of the “gap between aims and public comprehension” and said that her “original intention was misunderstood” for “yet another woman taken as a source of male pleasure.” 13Oppenheim, who was not even present for the Parisian restaging of her work, was again mistaken in the vortex of the surrealists. She did not exhibit with them again.14

Despite her dismissal of Breton’s organized circle, Oppenheim was active with loose factions of the movement and remained sympathetic while simultaneously carving out her own independence. This can be seen in Oppenheim’s Self-portrait and Curriculum Vitae since 60,000 B.C. to X (1966), which she made in response to a questionnaire sent from the Daily Bul, a loosely surrealist-affiliated publication by Pol Bury and André Balthazar. The query was “Who are you?” The india-ink drawing, which we can deem the “self-portrait” component, presents a bricolage of place, architecture, and nature, where a desert horizon fades into the mountains soon swallowed by an open sea. Stalagmites border an ancient rock doorway topped by a triangle with veins, a feather, some larvae, and a flower blossoming. Here, Oppenheim humorously deflects our expectations of a self-portrait, instead inferring her “self” within and amongst her light sketches of varied mythologies drawn from ancient architecture and civilizations. The “curriculum vitae” of the title is sketched in the corresponding text:

My feet stand in a cavern, on stones smoothed by many steps. The bear meat tastes good. Flowing around my stomach is a warm ocean current. I stand in the lagoons . . .thoughts are locked in my head as in a beehive. Later I write them down. Writing burned up when the library of Alexandria went up in flames . . .15

With this, Oppenheim declares her presence within the natural world and evokes civilization’s wrath as destroyer of her own writing, her own culture, her own preservation. Likewise, the active role of the cadavre exquis drawings depict a determined perplexity between artists and the surrounding movements that influence and shape them. Oppenheim plays the role of mischievous green goddess, looking down upon us as unholy spectators, erasing and poking fun at the artist’s posterity and prestige. This theme is also humorously depicted in an earlier painting, Sitzende Figur mit verschränkten Fingern (Sitting Figure with Folded Hands, 1933), in which the traditional sitting portrait is transfigured faceless. These looming nodes of erasure or anonymity in portraiture and authorship stand in contrast to Oppenheim’s struggles with the quick fame she both gained and resisted from Object in 1936.

This concept of a self-portrait drawn from the imagination and presented as an abstraction devoid of any representation of an individual self is similar to the unplaceable and unauthored collaborative figures in the newly found twenty-six cadavre exquis drawings. Both draw from or evoke the surrealist idea of dépaysment. Dépaysment recalls a vertigo of orientation or a disorientation between the spatial and temporal. This conception of displacement was largely inspired by the sixth canto of Les Chants du Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror, 1869), by surrealist literary muse Comte de Lautréamont (Isidore Ducasse). Lautr.amont’s definition of beauty as “the chance meeting on a dissection-table of a sewing machine and an umbrella!” 16was inspirational for the surrealists in their quest for the marvelous. Here, in these cadavre exquis drawings from so many years later, Oppenheim disorients herself from the paralyzing grip the movement once held on her, seeking liberation and spontaneous discovery, or rediscovery, from an activity she reclaims from the movement as simply a child’s game.

Meret Oppenheim and unnamed collaborators, Flora Thormannia, circa 1970s–80s. Pencil on paper, 11 ¾ × 8 ¼ in. Courtesy of Karma International.

Oppenheim’s collectively made drawings take us down a zigzagging line of shadowy creatures and underground sunsets, in which hula hoops embrace penises, jubilant swings dangle from cat whiskers, and monsters and demi-gods are united and liberated with outstretched tongues ready to mingle and greet the world. A forest of friends, feathers, and fears emerge, free of the restrictions of any one group, and exhibit a new kind of freedom. They are concurrently nude and well-dressed, chic and exposed. Made without pretension to art or any purpose beyond the process, the drawings show obvious signs of aging and creases, as if they were the leftovers of a furious and passionate engagement. They resist precision, cleanliness, and perfection, and are the better for it. They speak of an era when a regimented timeline of surrealism had been dismantled and an everlasting ether of its spirit can flap on without time or bother.

Presumably executed in the parlor of her grandparents’ home in Carona, where Oppenheim was introduced early on to an intimate enclave of artists and writers, these drawings passed the baton of collaborative child’s play to local Swiss artists and visiting international friends who would continue the traditions of collective chance and unbridled joy through the game of cadavre exquis. With the public debut of these works, first at Karma International and in upcoming retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and Kunsthalle Bern, we are presented with a more complicated roadmap to Oppenheim’s legacy than an oversimplified and fetishized association to surrealism. May this new circuit of viewership allow us to move beyond the early surrealist boundaries of Oppenheim’s fame into the forest of her friendships and her non-categorical nature in the beyond. 17

Brigitte Nicole Grice is an artist, writer, and filmmaker. She is presently based in London and Los Angeles working on her PhD in Film Studies (Creative Practice) at the University of Essex and an expanded documentary film on International Surrealism. She completed her MA at the California Institute of the Arts and has an undergraduate degree from Boston University in journalism and art history that she obliquely puts to use.