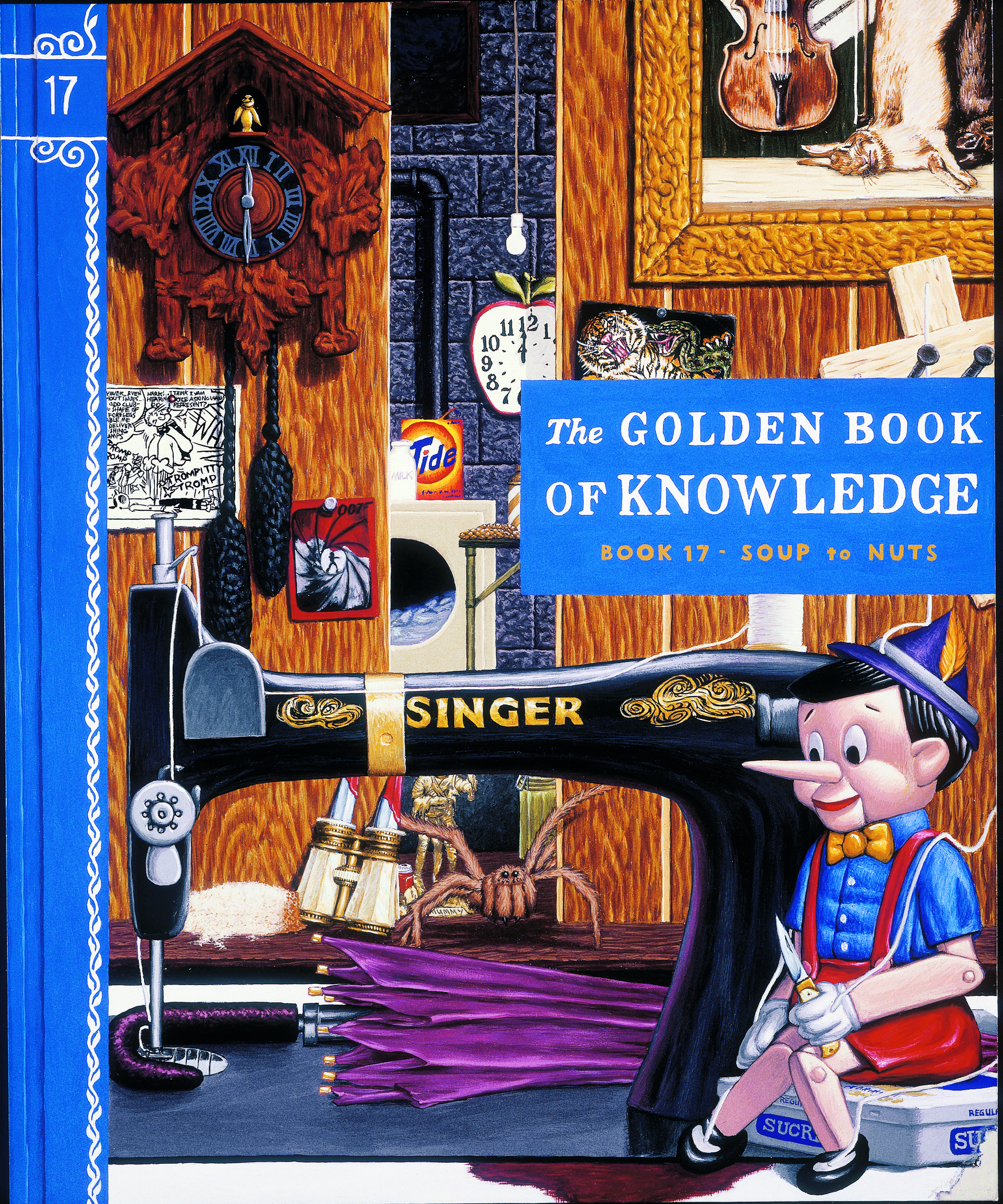

Maybe you had to be living in California in 1978, the year Jim Shaw completed his CalArts thesis—which was called, like the current exhibition at the New Museum, “The End is Here”—to know that art could not possibly compete with the insane power and creativity of mass media. Among many other markers announcing the technology worship that is now so central to American culture was the premiere of the original Star Wars movie in 1977. But in developing an art that encapsulates vernacular art, Shaw looked back to the print media of the twentieth century, some of which had spawned TV programs and movie series but still thrived in print form. Movie magazines, comic books, posters, paperback science fiction, and detective or horror novels, especially those that intersected with religion or other systemic visions of human history, became Shaw’s prime source material. Jim Shaw: The End is Here surveys the various ways the artist deployed these artifacts, including compiling, altering, distorting, extracting, re-drawing, and re-naming them, as he pursued a practice in which source material and the art made from it intermingle to present an enchanting and terrifying view of America.

Jim Shaw: The End is Here, 2015-16. Installation View, New Museum, New York, October 7, 2015 – January 10, 2016. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

The exhibition is astutely curated by Massimiliano Gioni and installed in a way that accommodates the architecture of the New Museum. Beginning on the second floor with Shaw’s art, the show moves to his collections of printed material and amateur paintings on the third floor, and to an installation employing theater backdrops on the fourth floor. While the space of this museum can feel like five giant stacked banker’s boxes, disrupting associations and desensitizing individual works, Shaw successfully exploits the building’s storage ambience, partly because much of the exhibition is composed of piles of things he collected. Beyond that, the show’s explicit post-art quality is fitting for a museum whose exhibitions often seem to call into question its very name: Is it the New Museum, as in a museum about art that is edgy and not yet accepted, or is it new in the sense of art that is giving up on art forever? Because the End that Shaw’s exhibition title refers to is not only the end of the world, derived from Shaw’s faux apocalyptic pamphlet of the same name, but also the end of art as we know it, the show engages with the museum’s perplexing mission and site in a deep way, endowing the space with impressive vitality.

One of the realizations Jim Shaw: The End is Here elicits is that the fliers at the bottom of the mailbox and the pamphlets and cards pressed into your hand on the subway contain messages in urgent need of interpretation. This is not because crazies have unique insights and Sunday artists love art in an old-fashioned, real way. Rather, what this show does is assemble all manner of vernacular materials concerned with belief systems that incorporate the imaginary—science fiction magazines, such as Amazing Stories; Seventh Day Adventist brochures; Mormon scriptures; and tarot cards—so that we can listen to what they are collectively saying.

To stand in the third floor gallery of these apocalyptic collectibles, named The Hidden World (undated), is to feel the determinants of the San Bernardino massacre in a deeper way than any sociological analysis can ever communicate. The sheer mass of material tells us that believers in a punitive totalizing prophecy are everywhere, and there are many more of them than of us, the passive art museum visitors. The garish colors and unconventional perspectives of the imagery, along with the ubiquity of lightning, fire, and explosions, say that these believers are bursting with anger and violence. They want the end to come soon, to be here, and they are devoted to making that happen.

In an alcove of The Hidden World gallery are busts from a Masonic temple arranged on a shelf. The busts designate 19 ethnicities, including an “Eskimo,” a “Persian,” and a “Hottentot,” all caricatures or cultural stereotypes of a fake multiculturalism that masks racism, intolerance, and undifferentiated hatred. Shaw does not comment on these artifacts but allows their implications to unfold within the viewer.

Jim Shaw: The End is Here, 2015-16. Installation view, New Museum, New York, October 7, 2015 – January 10, 2016. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

In like manner, Shaw lets the vintage photographs of American Mormons speak for themselves. Images of well-behaved children being instructed in prayer by a priest, who holds a girl’s hands or lays his hands on the head of a young boy, conjure the sexual abuse of children, domestic violence, bullying, and all the behaviors that, in the past two decades, have been revealed as the underside of religion in the United States. Shaw places these photographs adjacent to Christian pedagogical material threatening damnation for any behavior deemed non-normative. In the greater context of The Hidden World ’s surreal and fantastic images, this juxtaposition emphasizes the belief systems that permit tacit church approbation of destructive behaviors.

Psychoanalysts know that a serial killer or a mass murderer is typically a person who was abused during an early stage of development or witnessed the abuse of a parent. The “generative innocence” of childhood was denied to this person, and as a result no intimacy can ever be attained. Instead, “a killed self seems to go on ‘living’ by transforming other selves into similarly killed ones, establishing a companionship of the dead.”1 The biography of Syed Rizwan Farook, one of the two suspects in the San Bernardino massacre, was summarized in a few paragraphs in the New York Times. Included was the fact that Farook’s alcoholic father violently beat Farook’s mother and hurled appliances at her repeatedly.2 Yet, preoccupied with the Islamic ideology of the murderers, no media authorities seemed to comment on this evidence of trauma that is found at the root of all dispassionate murders. The interaction of childhood abuse and fundamentalist religion is one recipe for terrorism, and religious sub-groups that condone the beating or abuse of women are breeding grounds for dispassionate murderers. This is our future, and that end is here. Jim Shaw felt it coming; he read the pamphlets and saw through their advertised apocalypse to the true crisis we are now approaching.

Jim Shaw: The End is Here, 2015-16. Installation view, New Museum, New York, October 7, 2015 – January 10, 2016. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

Not all of the vernacular material Shaw draws upon is as harrowing as the apocalyptic ones. Thrift Store Paintings (undated) is a collection of amateur paintings that Shaw has been amassing from thrift stores and garage sales since the 1970s. Pre-dating the selfie and post-dating the society portrait, these delightfully narcissistic paintings of women posing seductively are infused with the dream of being looked at, as in the painting of an all pink nude woman who poses alluringly and grimaces at the viewer. The humor lies in the enormous gap between the celebrity culture the model and artist aspire to and the awkward, homegrown execution. What connects them to the apocalyptic material is the way they slip into the paranormal imagery, portraying the models as having pink or green skin or consorting with unidentifiable creatures or objects, as if (as is obvious) to be a celebrity is to be a step away from either a god or an alien. These works do not speak of violence, however; they speak of surrender to a power both transcendental and totalitarian, as do Shaw’s Oist works installed adjacent to Thrift Store Paintings. Oism, Shaw’s invented religion, is an amalgam of various messianic belief systems that focuses on the sexual aspect of ritual and obeisance to a spiritual leader, as in the video The Whole: A Study in Oist Integrated Movement (2009), where women dressed in harem-style costumes sway to unearthly music.

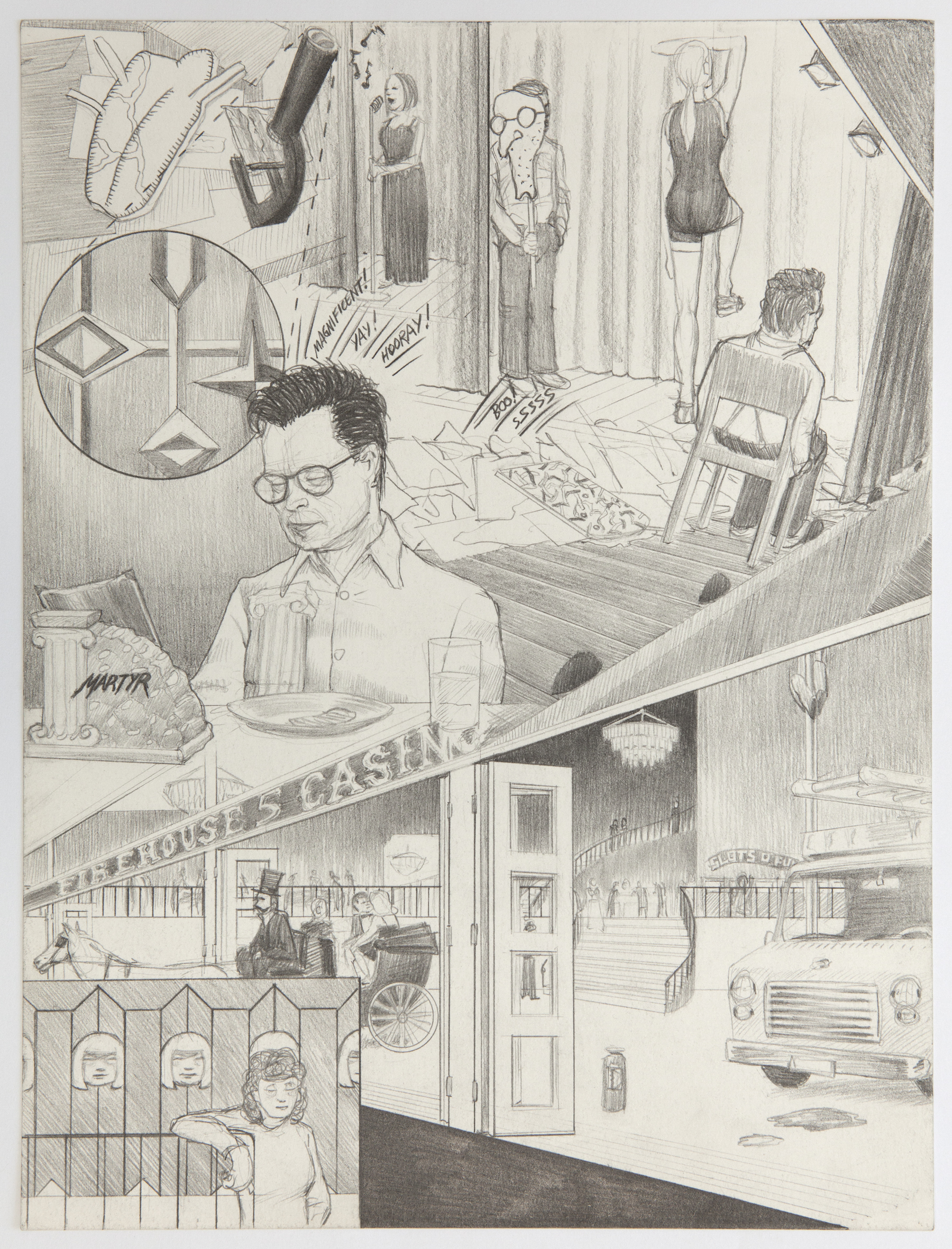

Jim Shaw, Dream Drawing (“On the TV movie bio of Frank Sinatra…”), 1996. Pencil on paper, 12 x 9 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

In the second-floor galleries, we see the core of the work that Shaw’s collections inspired. These photo pieces, from the 1970s, employ the trope of the double from science fiction movies. In Martian Portraits (1978), Shaw portrays an average American service worker (the label on his uniform identifies him as “Kent”) who has a double who is a Martian. The distorted faces series and the monster drawings also play on the idea of the “hidden” side of people; similarly, the stills of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, from the Zapruder home movie, are titled UFO Photos: Zapruder Film (1978–92), as if an event that occurred in reality has another life, and perhaps another meaning, among aliens inside a spaceship somewhere.

This preoccupation with a hidden, repressed, or unknown side generates Shaw’s abundant dream drawings, which in this exhibition rather unfortunately appear only in their smaller renditions, rather than Shaw’s wall-size drawings, which offer an overwhelming immersion in his dream world.

Jim Shaw: The End is Here, 2015-16. Installation view, New Museum, New York, October 7, 2015 – January 10, 2016. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

Nonetheless, these detailed, witty, skillful fusions of mass-media figures and event sequences with Shaw’s wishes and fears effectively demonstrate the permeability of the unconscious. Mass media has so effectively colonized the American psyche that our only name for our hidden wishes or drives is “Martian,” and once you’ve been imbued with racism, hatred, etc. via fantasy vehicles such as Superman (whose name is also “Kent”), you are dangerous.

Shaw’s altered theater backdrops in the fourth floor gallery continue the presentation of an alternative dreamlike world, here in the form of ghosts that look as if they’ve been found in an x-ray of the backdrops. In Judgement (2015), all manner of ghosts haunt the American homestead. In the original backdrop, the bucolic landscape, with farmers passing time on their front porches, was portrayed as watched over by heavenly angels. Shaw inserts a pernicious-looking grasshopper ghost, the ghost of a beggar, and the Ku Klux Klan, suggesting that the idyll of country life is haunted by blight, poverty, and political regression. In another backdrop, Moon (2015), “Art” is the elusive ghost of the backdrop’s vernacular art. Shaw’s self-assigned task is to elicit canonized Western art, as he does with the many miniature Magritte figures that infest the scene like vermin you were trying not to see.

Jim Shaw, The Golden Book of Knowledge, 1989. Gouache on board, 17 x 14 inches. The Eileen Harris Norton Collection.

My Mirage (1985–91), located on the second floor, is the centerpiece and masterpiece of the exhibition. In a sustained manner, the work investigates the American brand of normative fascism at the level of the unconscious. A graphic novel from before the era of graphic novels, it is the bildungsroman of our time, the story of a young man’s epic journey from a sexually repressed childhood, through the hippie world of drugs, sex, and rock and roll, to a rigid fundamentalism that is the opposite of the bildungsroman’s ideal of maturity. The brilliance of My Mirage is the way it incorporates the graphic design, typography, and language of pedagogical and polemical material that informs and deforms the protagonist in each stage. Shaw’s mastery of so many different styles of drawing and painting, which required him to both hone and devolve his skills, are one with his drive toward a totalizing vision of American culture, its demons, and its destiny.

Shaw’s imperative, so emphatically clear in this New Museum installation, is to create a kind of art that implicitly poses the following questions: What would the world be like if we could separate magic from religion and other ideologies? Would there be art? What would that art look like?

Annette Leddy is the New York Collector for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art and the author of the novel Earth Still (2015).