Cameron, Black Egg, n.d. Paint on cardboard, 11 × 8 inches. Courtesy of the Cameron-Parsons Foundation.

“Why Do I Not Know About This,” Margaret Haines writes in an essay about artist Marjorie Cameron, omitting the question mark. “I feel left out of something important, while no one is there to tell me what I have so completely missed.”1 Haines first came across Cameron in 2009, when she was one year deep in graduate school at the California Institute of the Arts and saw a survey of work by occult-involved filmmaker Kenneth Anger.2 She remembers being compelled by a figure who appears in Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954). The figure, whom Haines initially perceived as a man in drag,3 was called Cameron by those who knew her. She lived in greater Los Angeles from the late 1940s until her death in the 1990s. As Haines recalls in the essay, she had “strict red hair, a beak nose, a loose robe.” She struck “deeper and stronger than the white-woman-does-bitch-witch girlyness so connected to women of my generation.”4 Onscreen, Cameron mimicked and reimagined glamour, subverting the Hollywood divahood practiced by Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich, or Marilyn Monroe. But when she began digging for information on Cameron, Haines found the sources limited and at times conflicting.5 She realized that if she wanted to read about the woman who compelled her, she would have to do the writing herself.

Cameron, East Angel, n.d. Courtesy of the Cameron-Parsons Foundation. Photo: Alan Schaffer.

The Young Female Artist is the protagonist of this essay.6 Usually in her twenties or thirties, she takes on history writing projects in part because she has stumbled upon role models—women who give her insight into feminism, art, and life—that she has not found elsewhere. Often, because their stories are not familiar and their credentials have not been enumerated in too many press releases, the older artists she chooses as subjects have maintained a certain unruliness and complexity. The younger woman’s task becomes preserving that complexity, and narrating the artist’s life in a way that allows her to remain outside of the limiting frame of canonical narratives. It also becomes acknowledging a personal stake while giving her subject space and autonomy.

My interest in writing about younger women finding role models in women artists who preceded them grew from my own conversations on the subject with artists and others in the arts. These conversations began to happen so frequently as to indicate something significant. There were evenings in the car with artist Zoe Crosher, troubleshooting her plans to republish brazen writer Eve Babitz’s work and discussing the different ways that Babitz, who published her first book in 1974, had been treated in recent writing. There was the afternoon spent hiking with artist Corazon del Sol (daughter of artist Eugenia Butler and granddaughter of the gallerist Eugenia Butler), who discussed the installation she wanted to do at Highways Performance Space with Barbara T. Smith.7 Smith left her life as a Pasadena housewife in the 1960s to become a performance artist, and del Sol wondered how to portray Smith’s embrace of sexuality and vulnerability as brave, and also open up a conversation about femininity or uncertainty as counterpoints to current art world careerism. I had many conversations with curator Yael Lipschutz about her search for a venue for an exhibition about Cameron, whose eccentricity as an artist had never been treated fully as intentional. There was the night in October 2014, just after Cameron: Songs for the Witch Woman opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art at the Pacific Design Center, when Lipschutz introduced me to Haines, who described the difficulty and allure of writing about a woman so often misrepresented. The examples go on, and consistently the emphasis has been on how to have another conversation. How does one engage with these historical women artists in a non- revisionist way, without sublimating their nonconformity? What structure, style, and language work best?

——

Eight years ago, when the Museum of Modern Art held the symposium The Feminist Future: Theory and Practice in the Visual Arts (2007), curator Helen Molesworth gave the talk that would become her essay “How to Install Art as a Feminist.” She grappled with how to treat artists who only belatedly receive critical attention for their work, and also suggested that younger women have a particular, vested interest in this problem. Molesworth described a prototypical young female artist who “grows up in the halls of MoMA but doesn’t see her first Joan Snyder painting until it suddenly emerges one damp morning like a mushroom under a tree, at the Jewish Museum.” MoMA owns two paintings by Snyder, who started making densely physical abstractions late in the 1960s, but it has barely shown them; it was the Jewish Museum that gave Snyder her retrospective in 2005. “At this moment, does the young artist need the diachronic narrative?” Molesworth continued.8 Retrospectively installing a painting by Snyder between works by contemporaries such as Philip Guston and Barnett Newman might not help the young artist at all, she implied. In fact, installing art that has been left out for deep, complicated reasons alongside works that have been canonized for decades might even imply that erasure and its causes are best ignored.9

In her essay, Molesworth fantasizes about placing Snyder’s work in a room with one of Cindy Sherman’s color film stills from the 1980s, a loose 2008 abstraction by Amy Sillman, a glittery but gruesome 2003 collage by Wangechi Mutu, and a gaudy 2005 scene by Dana Schutz. Together, the works of this group of multigenerational women artists would convey an ongoing desire for expressive freedom but also ambivalence about self-expression and its baggage, which tempers that desire.10 (Schutz’s figures all stare silently with closed mouths; Sillman’s figures have opaque, heavy shapes obscuring their faces that make it impossible for them to speak). Snyder becomes, in this setting, part of a present conversation, and framing historical art in this way might mean “presenting it as crucial for recalibrating the effects of the new.”11 In other words, conversing, in an egalitarian way, with historically overlooked women artists may offer young women artists valuable tools for understanding and navigating today.

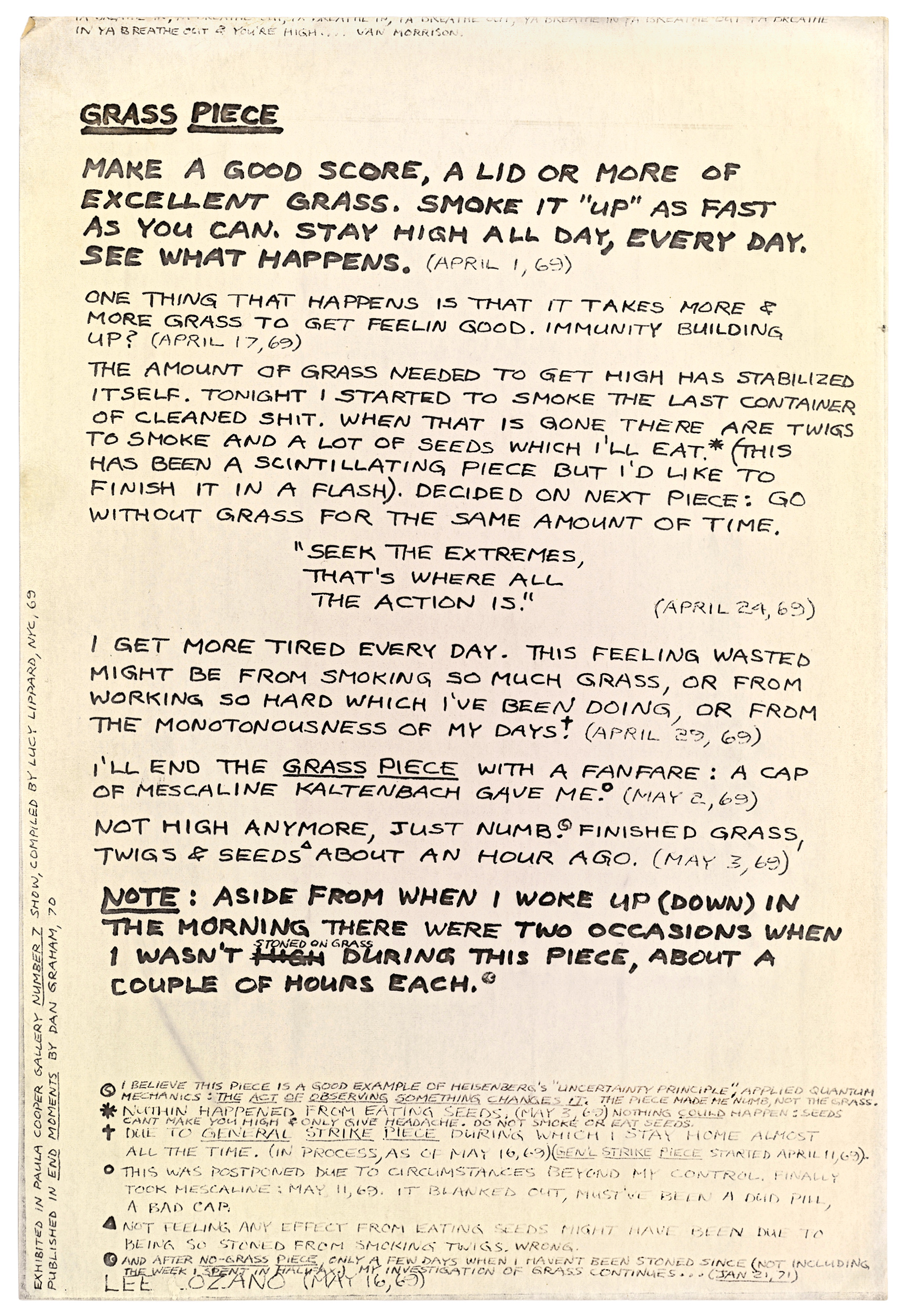

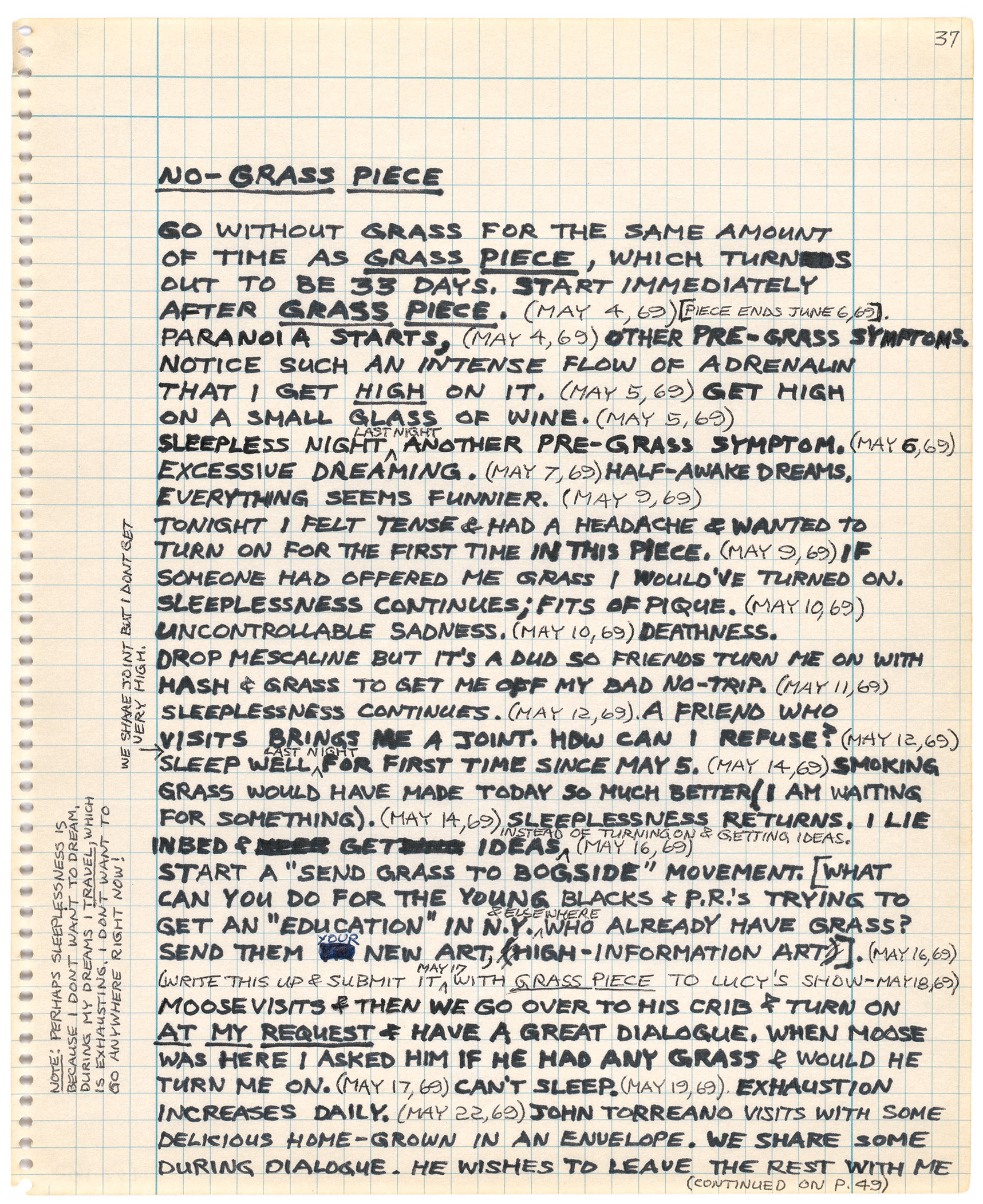

When writer and curator Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer organized her 2010 exhibition Joint Dialogue, her first public project about the work of audacious artist Lee Lozano, at the Hollywood gallery Overduin and Kite,12 she took a loose, non-hierarchical approach. For the most part, Lozano’s text pieces were on framed sheets of notebook paper, including Grass Piece (1969), in which the artist vows in writing to “stay high all day, everyday, see what happens.”13 Installing Lozano, who had started out as a semi-abstract painter in the early 1960s, alongside early text-based work by Dan Graham and Stephen Kaltenbach, younger male conceptualists who had been Lozano’s friends, Lehrer-Graiwer treated this show as a dialogue in its own right, one in which the curator seemed to be quietly participating. In the catalog, Lehrer-Graiwer includes a photograph of her own hand-written diagram, a plan for the show that outlines connections between Graham and Lozano, Lozano and Kaltenbach, and then lists the performances she plans to restage by acting out Lozano’s instructions (for example, by throwing Artforum issues into the air).14 The curator also discusses her own awe at the “strange, volatile,” “fucked up,” and “fucking hilarious” sensibilities of these three artists—Lozano in particular—whose projects had direct bearing on how they lived. “The best histories,” writes Lehrer-Graiwer, “are transformative and of use.”15

Lee Lozano, Grass Piece, 1969. Xerography, 12 5/8 × 8 1⁄2 inches. © The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy of the Estate of Lee Lozano and Hauser & Wirth.

Lee Lozano, No Grass Piece, 1969. Graphite and ink on paper, two parts, 11 × 8 1⁄2 inches. © The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy of the Estate of Lee Lozano and Hauser & Wirth.

It is easier in some ways to convey a sense of freedom in an exhibition, especially one in a gallery space that does not have to follow institutional protocol, than in a text. With no authoritative press release, no wall labels or vitrines, and with sculptures laid out unprotected on the floor, Joint Dialogue was able to convey a sense of freedom physically and immediately. The task of writing about the decisions that led to Lozano’s later obscurity, which Lehrer-Graiwer takes on in her 2014 book Dropout Piece, presents different hurdles. Among them is addressing the chronology of a career while acknowledging that one’s subject resisted notions of progress and professionalism. Titled after the last conceptual artwork made by Lozano, who gradually withdrew from exhibiting and participating in art world social circles early in the 1970s, the book declines to be overly confident of any interpretations it offers. It consistently uses strings of related adjectives, suggesting multiple possibilities. The text poses many questions, which become increasingly hypothetical in sections about Lozano’s less-documented later life: “How much control does an artist retain over what is known about her after her death?”16 Lehrer-Graiwer is of a different generation than her subject, and her distance could be seen as a benefit. She did not know Lozano at all, which gives her room to think speculatively and write open-endedly.

Critic Lucy Lippard portrayed Lozano as “exciting and eccentric” and “the major female figure in New York in the ’60s” in her 1973 book, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object.17 But Lippard, who knew the artist personally, did not say much publicly about Lozano beyond this until 2010, when she wrote a measured catalog essay for the artist’s retrospective at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. This is not indicative of any reluctance on Lippard’s part to write about artists she knew. It may, however, be due to specifically personal challenges Lozano presented for the critic. An intrepid, sometimes erratic personality, Lozano writes in her journal that she threw an unopened letter from Lippard on a pile and left it there around the time she decided to boycott women.18 Such actions may have made it hard for the feminist Lippard to champion Lozano.

In 1976, Lippard wrote an influential monograph on sculptor Eva Hesse, who had died six years earlier. Lippard had been quite close to Hesse; in her introduction to that book, she explains, “It would be a futile exercise as well as something of a rejection to attempt to ignore that knowledge.”19 In an effort to mitigate her subjectivity and “tread a fine and dangerous line between the art and the life,”20 Lippard relies on many observations from others and from Hesse’s own writings. Because certain reviewers posthumously framed Hesse as a tragic woman whose death made her work sentimentally compelling, Lippard had real reason to worry that, if she did not take matters into her own hands, her friend’s art historical significance would be misrepresented.21

The book’s first sentence asserts that the seventy sculptures Hesse made between 1965 and 1970, the year of her death, establish her as a major artist. “This is what she wanted, to be a major artist and acknowledged as such,” continues Lippard. “She knew she was ‘good’ even before her work had matured.” Decades later, in 2010, when Lippard lectured on Hesse at the Art Gallery of Ontario, she told another story about Hesse’s journey to being “good.” The artist had been reading Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949), thinking about de Beauvoir’s assertion that, to be truly great, a woman must forget herself. In her diary, Hesse wondered if she was capable of putting aside her own insecurities and self-scrutiny in order to focus on her work the way a (more confident) man might.22 She did well enough. Kirk Varnedoe, MoMA’s longtime chief curator of painting and sculpture, once wrote, in a book on Jackson Pollock, of Hesse transforming Pollock’s “liquid webs” into feminist statements.23 Both the Guggenheim Museum and Tate Modern’s websites frame her as an artist who adopted but also challenged the tenets of Minimalism.

Unlike Hesse, Lozano did not want to be “major and acknowledged as such,” or at least had serious internal conflict about recognition and what it represents. Before she began doing, in Lippard’s words, the “art as life thing,” she painted a series of methodical, minimal “wave paintings” made in long, single, often substance-fueled sessions. Any one painting from this series would have fit quite nicely next to a grid by Sol Lewitt, but Lozano resisted the work’s popularity, writing on notebook paper, “The wave series must be kept private, in the studio available only to those people I like enough to invite over… Make another kind of art for the outside world.”24 There could be no “forgetting herself” in order to be accepted as a serious artist. “When Lozano dropped out of the art world, her practice ceased as a career and became something else,” writes Lehrer-Graiwer in the catalog for Joint Dialogue. “I think her work continued and pieces happened that never made it out of her head onto paper.”25

Lehrer-Graiwer’s Dropout Piece, like Haines’s Love with Stranger X Coco and Lippard’s book on Hesse, relies on ample outside sources in an effort to ground Lozano in the historical context in which she lived and worked. But it is impossible to read the book as primarily about the past. In a brief article for the Brooklyn Rail, Lehrer-Graiwer reflects on her Lozano preoccupation: “I love this one-sided love affair; sometimes, it’s all I think about. She makes me venture to understand questions of being and psychology. What can art do to a life? Are you passionate? Confronting such a thrillingly unruly, defiant, and ballsy thinker is powerful to a sister. The desire to get high on ideas, to be obsessed and feel possessed is our common bottom-line.”26 Acknowledging the daring intensity of the life choices and persona of an artist such as Lozano makes her potential influence that much more powerful. That such choices and personas have been perceived and received differently in the past is one of the reasons for re-presenting these older female artists.

In 2009, when Haines left MoMA’s Kenneth Anger retrospective, she went home and Googled “Marjorie Cameron.” She found sensationalistic reports about the Scarlet Woman, the Whore of Babylon, and plenty of information from the perspective of occultists and acolytes of Aleister Crowley and Cameron’s husband Jack Parsons. But when Haines heard her first recording of Cameron, she realized, “It didn’t match at all this other vacated muse image of her. …Her knowledge of her own process and historical placement was very cognizant, well thought out and intelligent.”27 Among the recordings Haines heard was one from the 1980s, in which Cameron talks about how the Los Angeles County Museum of Art insufficiently credited a drawing of hers reproduced as part of an installation of Wallace Berman’s work, and she muses about how certain people from a given moment rise to the top while others remain in obscurity.

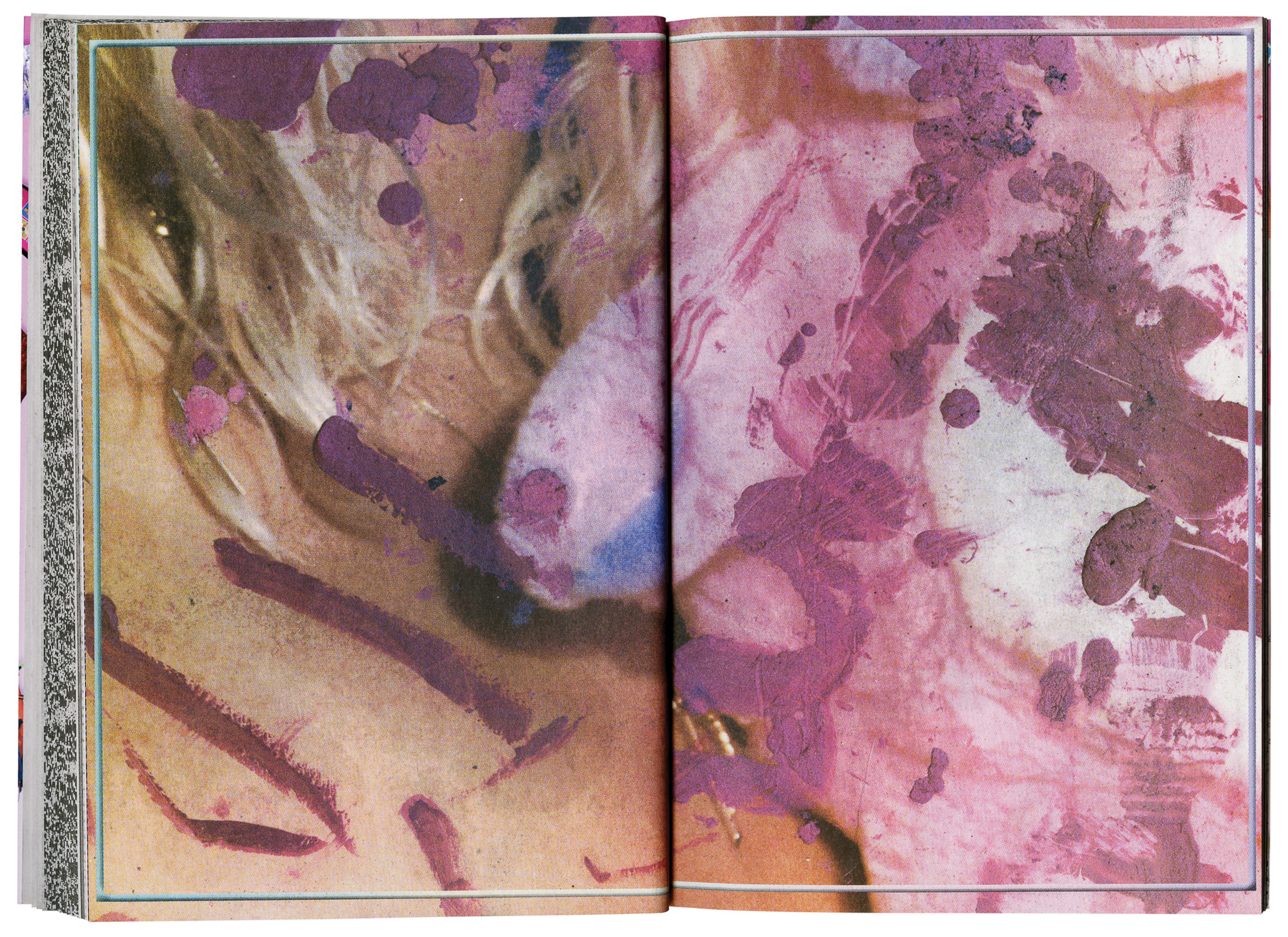

In Love with Stranger X Coco, Haines describes seeking out Cameron’s good friend Aya, a poet who lives in Mount Shasta. “I’m offered a window into what Aya calls The Women Who Were Left in the Shadows,” writes Haines. She quotes Aya, who asserts that what these women were doing was not “based on the same language” as their male peers: “None of Cameron’s writing is like men’s. Where you can’t say that about a lot of women writers of that time.”28 The shadowy space women such as Aya and Cameron chose to occupy offered no promise of recognition, but it did allow a woman to experiment with spiritual ecstasy and exercise creativity in ways, according to Aya, for which “there are no real words.”29

Margaret Haines, Love with Stranger X Coco, pages 86–87, 2012. Photo courtesy of Margaret Haines.

Margaret Haines, Love with Stranger X Coco, pages 70–71, 2012. Photo courtesy of Margaret Haines.

——

The first thing Molesworth does in “How to Install Art as a Feminist” is define feminism. She could have chosen artist Judy Chicago’s definition (“Feminism leads us to a future where these opposites [thoughts and feelings] can be reconciled and ourselves and the world thereby made whole”30); art historian Linda Nochlin’s (which involves women “using their situation as underdogs and outsiders as a vantage point…[to] reveal institutional and intellectual weaknesses in general”31); or even journalist-advocate Gloria Steinem’s (a feminist believes “in the social, economic, political equality of males and females”32). But Molesworth quotes Marxist historian Eli Zaretsky, who says that to be a feminist is to “revolutionize the deepest and most universal aspects of life—those of personal relations, love, egotism, sexuality, and our inner emotional lives.” It’s a definition that, Molesworth writes, “helps me remember that part of what I’m after, as a feminist, is the fundamental reorganization of the institutions that govern us, and that we govern.”33

This timely definition is not necessarily shared across fields. In May 2014, The Atlantic ran a cover story on “the confidence gap” that keeps working women from achieving the same levels of success as men.34 The story’s authors, Katty Kay and Claire Shipman, have written a book on the gap, and the backlash against their book has to do with its failure to address the systemic problems that favor a certain kind of “confidence” over another.35 Couldn’t a woman choose not to insert herself brashly into the tiers of success, not to apply for raises before she felt she was qualified (that women waited until they felt “ready” to advance their careers was cited as an indicator of less confidence), or not to vocally dominate in meetings and still be forceful in other ways? Wasn’t the underlying implication that the system would not be changed so women must further change themselves to beat the system? The prevalence of such assumptions makes it all the more necessary—even urgent—to tell the stories of the women left out because they never quite fit in, without simply folding them into histories they resisted.

The urgency is compounded by the fact that the influential survey WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, though it did include Lee Lozano, did not include Cameron, Judith Bernstein, Barbara T. Smith, or many other women artists whose bold explorations as individuals and artists have been documented but whose feminism was less in line with “the movement.” They were experimenting with mysticism or presenting the womb as the origin of the universe or embracing career-undermining extremes, not striving for inclusion in the “right” ways.

In a section of her essay titled “Girl Culture Girls Are Everything Girls,” Haines asks Scott Hobbs, who co-manages Cameron’s archive, “Was Cameron a feminist?”36 She describes her mind wandering as she waits for his answer. She thinks about her own “unpinned” feminism that is “post Riot Grrrl” and somehow aligned with the “girl power” of the 1990s, and quotes a 1997 article by rock critic Anne Powers: “Girl Culture girls…want the world and they want it now.”37 Finally, Hobbs responds: “I like the idea of a woman writing about Cameron. That is good, you can write about her being a feminist.” He also says Cameron read a 1916 text called “Woman and Super-woman” on the radio in the 1980s.38 Haines finds the tape in the archive and listens to the artist read: “It is the mission of woman to free her will and to attain consciousness…and then the Changing Order cometh swiftly.”39 Haines quotes this on the last page of her essay, before launching into nearly eighty pages of images, most related to the film about a girl named Coco that she had been making when her Cameron preoccupation began: a gorgeous snake handler, clumps of lipstick, beauty product billboards, surfers, desktops, ponies, Lady Gaga references, women in trances, and heart-shaped sunglasses overlaying an image of heartthrob Taylor Lautner. Her thinking about Cameron illuminates the whole experience of navigating art-making, navigating gender.

Catherine Wagley writes about art and visual culture in Los Angeles. She currently works as an art critic at L.A. Weekly and regularly contributes to a number of other publications.