On the night of November 26, 1933, John M. Holmes and Thomas H. Thurmond, having confessed to the kidnapping and killing of a young man, were dragged from their jail cells and hanged by a mob of many thousands in St. James Park in San Jose, California. of this much we can be sure. Because Holmes and Thurmond were white men, and because of the relatively late date of their lynchings, it was a tale frequently told. It was, in fact, a media sensation. But in the telling, the facts of the incident took on a certain fluidity. John Steinbeck’s “The Vigilante,” a short story based on the events of that night, swapped out Holmes and Thurmond for an unnamed African American.1 In his still controversial 1936 film Fury, Fritz Lang combined the two lynched men into one, made a hero of him and, in the narrative service of revenge and romance, spared him from the mob.2 The photographic record of that night has likewise been subjected to the exigencies of narrative necessity, revised from the very first to accommodate the conventions of genre and politics. Though the men were hanged at different times and from separate trees, the maker of one customary postcard souvenir of the lynchings (there were many such postcards) saw fit to produce a composite from two photographs in order to create the convenient fiction that the two men had been hanged from one tree.3on an entirely different register of photographic manipulation, which rendered the event invisible, if only momentarily, an entire edition of the San Jose News was confiscated the day following the lynchings. It was not because of any qualms about representing the cruelty of the lynchings themselves, but because a printed photograph displaying the nudity of Holmes’s hanging corpse so offended the city’s leadership.4

Four unique narratives provide four distinct departures from the otherwise ascertainable facts of the lynchings of John Holmes and Thomas Thurmond. The domains of literature, cinema, photography, and journalism each yield their own differently motivated dissimulations. In the telling of this hanging, every imaginable component of the tale–who, why, where, whether–has been, for wildly varying political motives, modified, synthesized, enhanced, or erased. Yet, taken together, they convey something more of the truth of the image of lynching in America than could any purely documentary representation. Together, that is, they form an image that has no singular and tidy referent. Instead, it’s an amalgamate, collective image containing something of the diachronic complexity of the phenomenon of lynching–its brutality, yes, but also its racialized, mediated, and participatory logic, its presentational and representational topoi or tropes, and its human and historical erasures. This image resists being set into form, resists representation.

Ken Gonzales-Day, St. James Park (The Wonder Gaze) 2006-08. Courtesy of the artist and Steve Turner Contemporary.

In his recent installation, The Wonder Gaze (St. James Park) (2008), Ken Gonzales-Day has taken on the sizeable challenge of granting this “mental” image of lynching a medium. Adhering to an unimpeachable historical logic, that medium is photography. The Wonder Gaze consists of three distinct but deeply interrelated elements. Two large photomurals, one positive, the other its negative, hang facing each other on opposite walls. The negative image is printed on disruptively textured, mirror-like mylar. A densely hung suite of fifteen framed, 4 x 6″ photographic prints occupies the connecting wall to complete the environment. Like the other representations mentioned above, including the confiscation of the San Jose News,5 the installation takes the hanging of Holmes and Thurmond only as its point of departure, preferring to allow the specificity of the event to fold into a generalized atmosphere governed by its own heuristic intent. But The Wonder Gaze is no simple repetition of those prior distortions; it is instead an exceptionally vivid moment of what we might call pictorial archaeology. The Wonder Gaze uses photographs to conduct and promote an inquiry into the structural conditions of lynching both as a phenomenon situated in history and as a phenomenon living through history, encompassing, though not condoning, the gamut of lynching’s presentational and representational conditions.6As Gonzales-Day shows us, photography (as a technology and as an episteme) is and was integral to lynching’s structural conditions, and for this reason there is no better apparatus for staging this archaeology than photography itself.

Encountering The Wonder Gaze at the rear of LACMA’s Phantom Sightings exhibition, we first see St. James Park (2006-08), a black and white photomural of cinematic proportions. A metonymic, frieze-like procession of some three-dozen men and women in fedoras and stoles is set off in sharp relief by a powerful burst of illumination against the pitch-black ground of night. Enough of these people, though not all, focus their attention upon the upper reaches of a lone elm to indicate that this tree is the nexus of their assembly. The image’s jarring contrast, so evocative of Weegee’s sensational photographs of violence, with his camera’s flash “scooping a searing, shallow foreground out of the night,” suggests something of the menace at hand.7Though no corpse is visible, this has the photographic look of murderous violence. In its “scooping,” however, the flash enabling this picture has left in blackness one crucial piece of evidence and the true object of this crowd’s fascination–the lifeless bodies of Holmes and Thurmond. But this is not the flash’s only erasure here. Three men at center right, for all their unmistakable presence, have been reduced to white silhouettes, offering only an almost physiognomic profile of type; their identities, like those of their victims, have been photographically erased.

Gonzales-Day did not take this photograph, but he did compose this photomural. Like the souvenir postcard, it is a composite assembly of separate photographs into one inexact but representative picture. Like Weegee, who in his pursuit of affect frequently dodged out unwanted background details, Gonzales-Day’s seamless retouching prioritizes the crowd and its reaction over the bloody target of its attention. As with Steinbeck and Lang, the identities and number of those involved have been radically suspended. And like the censors of the San Jose News, Gonzales-Day has erased pivotal photographic information. He did not set out to provide us with adocument of the specificity of this crime. Instead, he has given form to what the literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt might call the historical resonance of its representations: their “power to reach out beyond [their] formal boundaries to a larger world, to evoke in the viewer the complex, dynamic cultural forces from which [they have] emerged and for which [they] maybe taken by the viewer to stand.” To simply display a photographic document of this or any other lynching would trigger not resonance, but the same disinterested and morbid wonder that has always plagued exhibitions of lynching souvenirs. Exhibitions such as Without Sanctuary (2000) do little more than reproduce the ghoulish spectacle of the crime that they ostensibly condemn.8 Gonzales-Day’s St. James Park mural stages the scene of wonder but conceals its referent; it is to a degree about wonder, but not of it.

I have mentioned two meaningful absences at work here: those of the lynched bodies and of the three flash-burned men. But there is another, a structuring absence, as in all photographic representations: that of the photographic apparatus.9 It is precisely through the first two erasures that this third absence is made explicit. The analog (but no doubt digitally enhanced) flash, which has burned out the identities of the three men in the foreground, and the act of dodging (again digital), which has removed Thurmond and/or Holmes, both indicate the hand of the image-makers and their technologies in constructing the scene of lynching. This is important because the invisibility of the photographer in the photographic image, and particularly in the traumatic photographic image, has long supported the double myth that photography has not in some way produced the object of its capture, and that the photo- graphic image is not intrinsically a politically motivated instrument. Assessing this condition, Griselda Pollock recently observed “the photograph formally evacuates the signs of its own productive hence ideological location, its purpose.”10 By so drawing attention to itself, Gonzales-Day’s handling of flashing, burning, and dodging restores those evacuated signs and reconnects, at the level of form, the photographic image/act with its historical and political agency. In The Wonder Gaze’s photomural composite of the scene that night at St. James Park, both the lynchings’ victims and their observers (who are also potentially its perpetrators) are now erased; they are not the object. What remains in their place is the fact of photography itself at the lynching tree.

Ken Gonzales-Day, St. James Park, 2006. Lightjet print, mounted on cardstock. Courtesy of the artist and Steve Turner Contemporary.

The suite of small, framed prints adjacent to Gonzales-Day’s photomural compels further critical engagement with this photographic interpellation. On view are reproductions–likewise subjected to Gonzales-Day’s photographic interventions–drawn from the all too plentiful archive of souvenir lynching postcards. Gonzales-Day’s project has involved a process of recovering an otherwise lost history of lynching in California, and considerable archival dexterity was involved in the location of their originals. Looking closely at these, we discover through our own process of investigation that two of these postcards served as source images for the (now obviously) composited photomural to our left. Within the formal logic of The Wonder Gaze, the intervention of the photographic apparatus (camera, darkroom, Photoshop, etc.) in constructing meaning is now undeniable. What we see has only the most remote indexical bearing on the scene it could be assumed to picture. Like all history, it is a model assembled from the archive; it is lynching’s imagein the historical imagination.

Ken Gonzales-Day, Erased Lynching (1933) 2006. Lightjet print, mounted on cardstock. Courtesy of the artist and Steve Turner Contemporary.

Finally, there is the negative, mirrored element which, by virtue of our presence between it and its positive, optically suggests the rhetorical work of including us in the mob of ghoulish spectators, a consideration that has become necessary in light of such recent spectacularizations of lynching as Without Sanctuary. But more importantly, including the viewers within the work’s mise-en-scene and insisting upon our participation in constructing meaning echoes Gonzales-Day’s project of critical looking and archival discovery. Because the installation offers little to arrest or disturb the impatient or uncritical viewer–its rewards unfold slowly and viewers who linger have necessarily entered into the active process of understanding, criticism, reflection–it is not wonder but resonance that is reflected in the mylar screen.

What of this resonance? What “complex, dynamic cultural forces” does this photographic inquiry set into motion? There can be no concise answer, but the experience of James Cameron, as discussed by historian Shawn Michelle Smith in a recent essay on the visual culture of lynching, is instructive. Cameron’s extraordinary experience of surviving the murderous fury of a Marion, Indiana, lynch mob in 1930, a mob whose violence took the lives of two other African American men that night, is recounted in his memoir in what Smith describes as “astonishingly…photographic terms”:

Abruptly, impossibly, silence fell over that raging mob, as if they had been struck dumb. No one moved or spoke a word. I stood there in the midst of thousands of people, and as I looked at the mob around me I thought I was in a room, a large room where a photographer had strips of film negatives hanging from the walls to dry…A brief eternity passed as I stood there as if hypnotized. Then the roomful of negatives disappeared and I found myself looking into the faces of people who had been flat images only a moment ago.11

The presence of photography in this passage, and thus at the scene of lynching, is unmistakable. Cameron’s experience testifies to lynching’s status as already photographically determined, and anticipates both the banal darkroom activity that would immortalize his own would-be murder and the “flat” collapsed space of the image that would emerge and proliferate from that darkroom. Recent scholarship recognizes that photography is not simply a technology of documentation, but is one that is structurally integral to the cultural logic of lynching in toto. “Photography,” Shawn Michele Smith notes, “documented lynching but also played a role in orchestrating it.”12The lynching that Cameron survived was itself photographed. As Smith explores in considerable detail, one of these photographs, taken by Lawrence Beitler, achieved such ubiquity in the press that in many ways it has come to stand as the very icon of lynching in America, as the image around which debates about lynching and its representations revolve. Photography’s pervasive witnessing enabled lynching’s initial “justification” by supporting the crime’s necessary myth of racial identification: it rendered race visible. And photography promised, through mass reproduction in postcards and in the press, to broadcast the act’s catalytic message of racialized terror.13 In a circular system, photography both fostered a concept of criminalized racial difference, thus rationalizing lynching, and documented and disseminated the brutal consequence of this rationalization.

With race so integral a concept to any negotiation with the history and photography of lynching, it is necessary to note that, despite Holmes’s and Thurmond’s Anglo-American identities, a wall text accompanying The Wonder Gaze at LACMA indicates that the installation is “part of [the artist’s] project to recover the largely forgotten history of white-on-Mexican lynching in the Southwestern United States,” a characterization that has already been uncritically repeated in review essays discussing the Phantom Sightings exhibition.14This observation, while not true to the facts of the source imagery, is fundamentally correct; the historical, institutionally sanctioned invisibility of the extra-judicial executions of Latino bodies is a key referent of Gonzales-Day’s conspicuously absent bodies. Nonetheless, it raises problems that we elide at our peril. LACMA’s language suggests that the lynching of one or more Mexican men or women at St. James Park is the subject matter of Gonzales-Day’s source photographs for The Wonder Gaze. This suggestion, to make only the most obvious (and perhaps generous) point, is misleading to the viewing public and denigrating to the memories of the actual victims.15 The moment a photographic image’s supportive text willfully diverges from the verifiable facts of that image’s subject matter is precisely the moment where we encounter if not ideological dissimulation, then at least the potential dangers posed by the absorption of recognizable archival photographs of injustice into the operations of allegory, grossly distorting the profound connotation of historical and situational specificity these archival images bring with them.

Ken Gonzales-Day, The Wonder Gaze (St. James Park), 2006-08. Phantom Sightings, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In The Wonder Gaze, Gonzales-Day’s erasure of specific identities enables the melding of the general and the particular necessary to an aesthetic engagement with traumatic images, an engagement that potentially yields a critical perspective.16 However, this move in the work is compromised by the museum’s unfortunate didactic re-insertion of specific and factually faulty identities. If such images as those activated in The Wonder Gaze–images so carefully rescued by Gonzales-Day from institutional archives all over California during his documentation of some 350 lynchings in the state–are to be textually framed in a responsible way, they demand anchorage to whatever can be known of their factual circumstances. This is exactly how photographic evidence pertaining to the St. James Park lynchings is presented by Gonzales-Day in his book on the photographic history of extra-judicial executions in California, Lynching in the West: 1850-1935, where we learn, in great detail, about Holmes and Thurmond and their disastrous last days. The rhetorical mechanics of Gonzales-Day’s erasures may not depend for their corrective efficacy on the contextual support provided by Lynching in the West, but the obfuscation introduced by LACMA’s misleading didactic threatens to shift the artist’s photographic erasures from provocations to, well, straightforward historical negation.

Restored as a referent, the whiteness of Holmes and Thurmond’s bodies, itself historically “invisible” as race, however necessary its recognition is to the history of lynching in America, produced its own erasure. Just as their hanging facilitated a national discussion about lynching, it also obscured the particular racial politics of lynching in California. As Steinbeck’s pragmatic substitution of an African-American victim or Lang’s substitution of an innocent white man instantiate, the St. James Park lynchings, in effect, became a screen upon which any number of identities could be projected in the service of voicing the appropriate and necessary condemnation. In California, lynching was, as Lynching in the West has demonstrated, a crime directed predominantly against Latino and Hispanic populations.17 To allow for the specificity of the St. James Park incident to stand in for lynching in California is to elide or at least displace lynching’s more familiar integral logic–white racism–from the discussion. As historian Stephen J. Pitti has discussed, many ethnic Mexicans in northern California later remembered the lynching of Holmes and Thurmond as one more episode amidst an epidemic of mob violence against Mexicans, so frequently was the fury of the mob directed against them.18 Factually, this projection, like Steinbeck’s, was incorrect; but in substance, it was reasonable. In The Wonder Gaze, the status of the Holmes and Thurmond lynching as the most photographically visible and therefore knowable lynching in California history stands as evidence only of photography’s radical inadequacy to its own historical evidentiary burden.

The photographic presence of Holmes’s and Thurmond’s bodies, then, in addition to producing deadening wonder in the face of grisly murder, would also have re-directed analysis away from the predominant and, until recently, historically marginalized racialized logic of lynching in California. It also would have clouded the artist’s central concern, only alluded to at LACMA: the reciprocal dynamics of photography and race in the construction of lynching in America. It is only in their absence, that is, that the question of photography’s punitive relation to identity seeps, enigmatically, to the surface. For this reason, The Wonder Gaze must be understood as only one component in a larger project–one which, in accord with Gonzales-Day’s insistence upon the inadequacy of the photograph to any thorough reckoning with history–comes into sharper focus when understood in relation to another work by the artist that was on view, luckily, just across the street.

With his installation Of Physiognomy & The Love of Mankind at Steve Turner Contemporary, which coincided with the LACMA project for two weeks in April 2008, Gonzales-Day extended his thesis with photographs, drawings, and a sculpture. The sculpture, titled A sure and convenient machine for drawing silhouettes (2008), will be the focus of the remainder of this essay. Shifting away from The Wonder Gaze‘s consideration of the operations of lynching’s photographic documentation, this exhibition acts in the conceptual space opened there to conduct an inquiry into the roots of racial violence and their concealment within the photographic medium’s very ontology.

Thomas Holloway, A Sure and Convenient Machine for Drawing Silhouettes, c.1792. From Johann Caspar Lavater, Essays on Physiognomy: Designed to Promote the Knowledge and the Love of Mankind (London: John Murray, 1792). Photo courtesy of the author.

If photographs can be seen as essential components in the conduct of lynching’s hateful agenda, the basis of this application can be located just as effectively in the origins of the technology itself, in the very impulse that led to photography’s invention. It is a truism of photo history that the desire to chemically affix the shadow to a support grew out of the radical socio-economic changes of modernization and its attendant reorganization of culture. A central premise of many of these histories is that the West’s new middle classes required a fast, cheap, and easy technology for the production and stabilization of their own likenesses, and thus the consolidation of their newly formulated and otherwise all too slippery identities. Accordingly, these histories offer up a number of pre-photographic technologies in support of their argument, tracing a lineage from photography back through its mechanical and more primitive predecessors. The physionotrace was a device that mechanically transmitted the draftsman’s gestures of tracing the sitter’s profile through a viewfinder to paper (with strikingly good results). The pantograph was a similar if simpler mechanism for reproducing extant silhouettes. Preceding both inventions was the idea of the silhouette machine: a chair which fastened the subject in profile between a candle and a sheet of parchment, thus enabling the accurate and easy tracing of the shadow’s outline.19 Voila, a portrait.

The silhouette machine, an object whose description suggests an innocence that belies its catastrophic implications, stands as a remarkable emblem of the irreversible braiding of indexical representation and racialized pseudoscience that would ultimately support lynching’s dehumanizing rationale.20 A sure and convenient machine for drawing silhouettes is Gonzalez-Day’s sculptural rendering of this apparently never before fabricated chair.21 Gonzales-Day drew his model for the chair from Essays on Physiognomy, Designed to Promote the Knowledge and Love of Mankind (1788-89), by the eighteenth-century pastor and father of “modern” physiognomy, Johann Kaspar Lavater. In his text, Lavater adapted the heretofore explicitly metaphysical project of understanding and ordering the souls of men through the body (a subject covered at length in writings originally thought to be Aristotle’s but now attributed to the pseudo-Aristotle) to conform to the scientific episteme of his own day.22He did this by reducing the relevant physiognomic data from the overwhelming semiotic plenitude of the human face to what art historian Victor I. Stoichita has called the Urbild, or the absolute minimum essential index offered by the traced silhouette.23Historians of photography are not wrong to recognize in Lavater’s impulse a forebear of the indexical portrait-making mechanism of photography, but it is in that impulse’s promise of objective knowledge about the unknowable and contingent interiority of the subject that his chair anticipates less the camera than the full weight of that technology’s subsequent taxonomizing applications.

Ken Gonzales-Day, A sure and convenient machine for drawing silhouettes, 2008. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Steve Turner Contemporary.

As Shawn Michelle Smith has observed, the impulse to consolidate the identity of the middle class subject through photographic portraiture and thus make legible its wholesome, normative soul carried its own structural necessity of differentiation:

The desire…to deem their own photographic portraits auratic led them to categorize and to classify–to monitor–the representations of others. Studies of the criminal body, in particular, answered to middle-class concerns about the essences some bodies might mask and hide, and attempted to make those bodies transparent to the technologically aided, professional middle-class eye.24

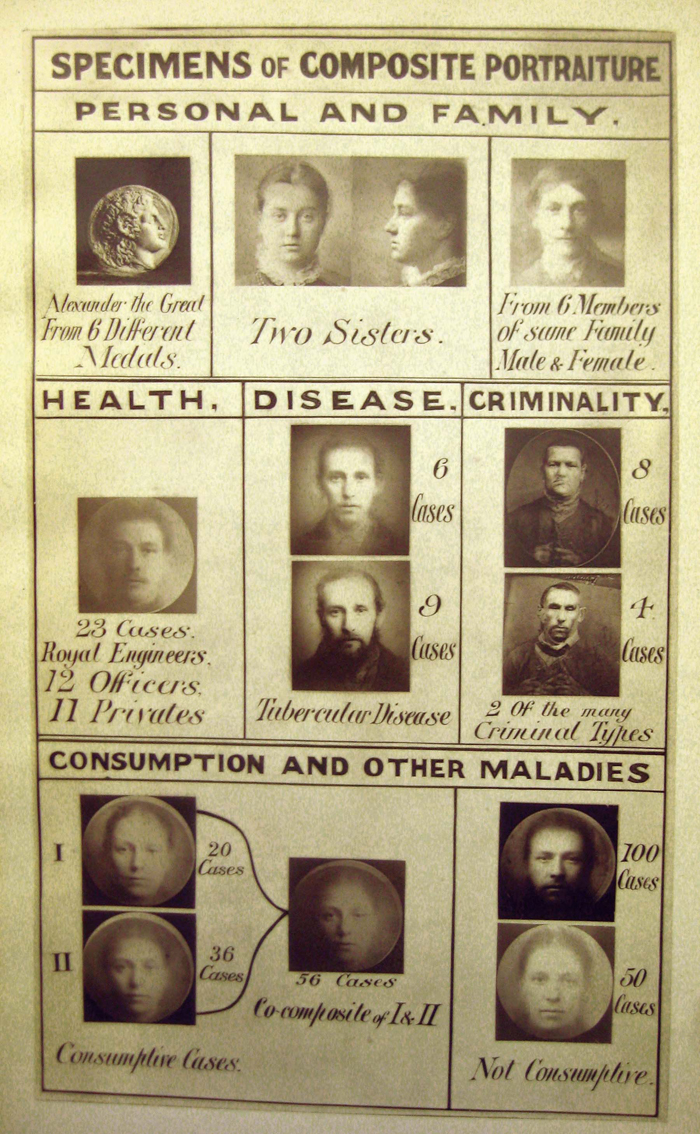

From Cesare Lombroso’s criminal pathology of the late nineteenth century, which served to identify criminals prior to their crime on the basis of photography and other indexically derived data such as blood pressure readings and handwriting samples, to the eugenicist Francis Galton’s explicitly racialized photographic program of identifying “impure” bloodlines and physiognomic indices of probable criminality, the indexical representation of the body was almost from the very start recruited into the project of rendering difference visible, and not just undesirable, but criminal.

César Lombroso, Portraits de Criminels, c.1888. From idem., L’Homme Criminal: Atlas, 2nd edition, (Paris: Felix Alcan, 1895). Photo courtesy of the author.

That this categorical collapse was operative in the American Southwest and had bloody implications for those identified as visibly different, and therefore criminal, is illustrated nowhere better than in the nineteenth-century philosopher Josiah Royce’s 1886 observation on the character of vigilante jurisprudence in the California of his day: “The foreign miners, being civilized men, generally received a ‘fair trial,’ as I said, whenever they were accused. It was, however, considered safe by an average lynching jury in those days to convict a ‘greaser’ on very moderate evidence if none better could be had. One could see his guilt so plainly written, we know, in his ugly swarthy face, before the trial began.”25

Francis Galton, Specimens of Composite Portraiture, c.1883. From idem., Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development (New York: Dutton, 1919). Photo courtesy of the author.

Physiognomically informed photographic technologies of racial taxonomy and criminology developed in virtual lockstep with the bloodlust of Southern Californian lynching committees. But can we locate so much in so simple an artifact as Lavater’s silhouette chair? Writing in the late eighteenth century, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, a German scientist, satirist, and contemporary of Lavater, suggests that as much was apparent from the very start: “If physiognomics ever becomes what Lavater hopes it will be, then we will begin to hang children before they commit the crimes that deserve the gallows; a new kind of confirmation ritual will be practiced every year. A physiognomic auto-da-fe.”26

In manufacturing Lavater’s proposed but un-built silhouette machine, Gonzales-Day has (again) given material form to the otherwise nebulous kernel of photography’s physiognomic unconscious. As an idea of the enlightenment imagination, Lavater’s chair could continue to serve as its own structuring absence, a ghost of a rumor haunting the medium. However compelling as an idea, the banality of this rickety chair as an object belies the assumption that through the simple recording of his shadow, access to some kind of total–even pathologizing or criminalizing– knowledge of man might be had. As a concept, this machine for producing soul-assessing indices embodies the conceptual basis for the pseudoscience of both Lombroso and Galton and their increasingly malignant intellectual heirs, from lynch-mob mania to Nazi rationalism. But sitting there, on the floor of Steve Turner Contemporary, with weight and mass and wood and screws, it is too fragile a thing to support the full burden of the enlightenment principles run amok that it ostensibly emblematized. And how little of value its indices have ultimately laid bare! As Gonzales-Day’s The Wonder Gaze so deftly demonstrates, it is not just through the photographer’s power to secure the shadow that our knowledge of the world is enhanced, but also through the power of that photographer to disrupt such easy, and disastrous, determinations.

Jason Hill is a doctoral candidate in art history at the University of Southern California and a 2008-09 Luce/ACLS Fellow.