The Marin Headlands sit sentry at the very tip of the San Francisco Bay, the point at which California wraps itself around a tremendous bite of ocean and nearly closes its lips to chew. Minutes north of San Francisco and a world apart, the area was made a national park in 1972; in 1982, it became the distinctive home of Headlands Center for the Arts. The air is damp, cell phone reception is nil, and the landscape feels empty. The center comprises a complex of structures that encircle a grassy field. Artists take up residence in several colonial-style homes for two or three-month stints, and a former soldiers’ barracks holds large, airy studios. The ocher basketball court in the vintage gymnasium smells more of ocean than sweat. All of the buildings date to 1907, and the Marin Headlands’ military history. Officers and their families originally lived in the houses; the central field was the site of morning bugles and target practice. Soldiers shot hoops and their children roamed afield, collecting rocks and sticks and spent gun casings.1

The hub of the Headlands campus is the Main Building, where staff has offices and guest chefs prepare evening meals for residents. Inside the Main Building are all but two of Headlands’ flagship permanent installations, although “installations” is not exactly the correct term. These artworks are a genre all their own, a genre that might be more aptly labeled “artist-led renovation.” In the past 30 years, eleven artists, some working in pairs, have been commissioned to rehabilitate and renovate the original military structures, adapting the buildings to the needs of an arts organization while also creating distinctive artworks. The oldest of these is David Ireland’s 1986 Rodeo Room and Eastwing; the newest, completed in April 2016, is The Key Room, by artist Carrie Hott.

View of Marin Headlands from Headlands Center for the Arts’ campus in Fort Barry. Image courtesy Headlands Center for the Arts. Photo: Andria Lo.

Ireland’s work at Headlands casts a long shadow and remains central to the institution’s identity. Ireland is cherished in San Francisco but little-known elsewhere; he left the Bay Area only briefly, for a disillusioning stint in New York. A conceptual artist who also worked as an insurance broker and an importer of big-game skins from Africa, Ireland didn’t turn to fulltime art making until he was 44, when he purchased the rundown Victorian home that would become his signature work. Ireland tended to this house for thirty years, refining his practice with each intervention. He removed bits of molding, stripped wallpaper, and coated the walls with a polyurethane varnish that preserved and burnished water stains, smoke smudges, and patchy scuds of aged paint. The home is minimally adorned with a few whimsical touches, and the palette is that of a threadbare blanket. The building, which housed the arts non-profit Capp Street Projects for many years and is now open for tours, has been described by the poet John Ashbery as “a work of art that can be lived in.”2 Ireland’s artistic accomplishment was to wrest decay away from time and take hold of it himself.

When Headlands commissioned Ireland, they charged him with rehabilitating the Main Building’s second-floor meeting rooms and central stairwell. Working with sculptor Mark Thompson and 24 young artist volunteers, Ireland completed the installation in a year, tediously stripping paint from the intricate tin ceiling with dental tools and coating other walls with copious layers of lacquer. Rather than eradicate the passage of time or smother it with the kitsch of manufactured time (as in so many hip restaurants and Anthropologie stores), Ireland burnishes the patina that blooms from many days and years of human use. The rooms are proudly old, and Ireland offers them a dignity that American culture rarely extends to the elderly. Even more unorthodox, Ireland’s carefully preserved stains and fissures suggest there is something punkish and sensual in aging itself. If the work seems like exemplary detritus porn, it is the sex-positive kind. The building is happily complicit in the spectacle of its decay.

Other permanent installations at Headlands followed Ireland’s lead. They do not stage a return to an immaculate past, but call out the texture of what happened before the artists arrived. The unisex bathroom, known as The Latrine (1988), is an especially spectacular experience. Artists Bruce Tomb and John Randolph made only small changes to the original facility—the toilets, sinks, showers, and urinals are all Army issue—but these changes transform the privy routine into a discombobulating bit of theater. The stalls are partitioned by absurdly thick slabs of steel, and disconnected urinals line the east wall, conjuring a line of soldiers emptying their bladders en mass. The space is a cavernous echo chamber: the clanks and clangs of the stalls, heeled shoes on concrete, zippers, and flushes all reverberate wildly. There is no nod toward privacy, rest, or comfort; using the toilet entails an uneasy combination of private and public. The installation captures what Executive Director sharon maidenberg meant when she described the Headlands residency as “difficult.”3

Artist Ann Hamilton’s restoration of the kitchen and dining room, Mess Hall (1989), is the exception to the prevailing aura of austerity. This space is all homey warmth. Hamilton added two handmade hearths for baking, banquet tables of ancient wood, and faint impressions of culinary herbs stenciled on the walls; she outfitted the kitchen with mismatched plates, worn cloth napkins, and open pantry shelves. Food is served family style in plentiful amounts, and residents collectively do the dishes before dessert. Whereas Ireland saw the solitude of Headlands as its defining virtue—during an interview, he advised his interlocutor to visit only when it was empty—Hamilton supplies a stage for community.

David Ireland, Rodeo Room, 1987. Commissioned by Headlands Center for the Arts, Marin Headlands, California. Image courtesy Headlands Center for the Arts. Photo: Andria Lo.

After an eight-year hiatus from permanent installations, Headlands recently commissioned a new project by Oakland artist Carrie Hott. The site of Hott’s intervention is a small room on the ground floor of the Main Building, down the hall from the kitchen and adjacent the bathroom. Hott was charged with transforming this room into a space that accomplished two purposes: to orient drop-in visitors to Headlands, and to present an archive of the institution’s past.

The first mandate solves a practical problem. Visitors enter Headlands’ Main Building expecting to see art, but the art therein is so subtle as to appear non-existent, and they leave perplexed. (Residents’ work is not routinely displayed or exhibited.) The second charge of Hott’s installation—to present an archive—stems from the room’s previous use. From 1989 to 2014, it was an installation called The Archive Room, and it was the site of a quaint ritual. Visiting artists left behind a memento of their stay: a slab of rock, an abandoned sculpture, a desiccated paint palette, a cooking pot, and hundreds of other things.

Subject to no intervention besides a bit of dusting, the objects grew in number and became more and more heterogeneous in scope. They were placed willy-nilly around the small room, tucked beneath and stacked on top of each other, creeping toward the door. By the time Hott drafted her proposal, the room had taken on the appearance of a junk shop. Pinecones and rocks were nestled between withered branches; antiquated liquor bottles lined the windowsill; the walls supported crutches, feather headdresses, and a dangling skein of yarn. The Archive Room had no semblance to an archive, but was rather the archive’s nemesis, the figment of chaos-run-amuck that haunts the nightmares of a true-blue archivist.

The Archive Room, 1989–2014, Phoebe Brookbank and Machele Civey. Commissioned by Headlands Center for the Arts, Marin Headlands, CA. Image courtesy Headlands Center for the Arts. Photo: Andria Lo.

When Hott began dismantling the room, she found over a thousand individual things. Objects had been left from Headlands’ inception, including remnants of the building’s renovation. Scrap that seemed too precious to toss was stowed here, as were objects found on the grounds and in long-abandoned closets and cupboards. A gallon-sized tin labeled “MPF: Multi-Purpose Food,” produced by General Mills for 1960s-era fallout shelters, was rusted but intact; a can of black-eyed peas, equally old, had been opened and emptied. There was a mummified possum, a cutting board split in two, a bit of bed frame. In 2001, the artist Ray Beldner did a performance that involved throwing computers and telephone books out the window; the detritus was preserved in a Plexiglass box attached to the wall. Mel Chin’s luggage tags were once part of the archive, but they were apparently stolen.

“You take an object from your pocket and put it down in front of you and you start. You begin to tell a story.”4 Thus Edmund de Waal describes his process of writing about his inherited collection of Japanese netsuke (carved figurines) in his memoir, The Hare with Amber Eyes. Hott’s starting point was the same. Like a child who unearths a mysterious bauble in the backyard, she began by extricating each item from the surrounding morass, wiping it clean, holding it in her hand. Made celibate by a berth of white space, the objects spoke. They seemed to again exist in their own right, with the singularity their original owners would have recognized. By reframing the objects “within a world of attention”—the crux of a collection in Susan Stewart’s analysis—Hott began alchemizing an artwork from a pile of old stuff. 5

Carrie Hott, The Key Room, 2016. Commissioned by Headlands Center for the Arts, Marin Headlands, California. Installation of archive objects in the Eastwing on opening day, March 20, 2016. Image courtesy Headlands Center for the Arts. Photo: Andria Lo.

Naturally, Hott inquired of staff what was left by whom and when and why. Residency Manager Holly Blake, who has worked at Headlands some 28 years, could recall the story behind the can of SPAM, the giant cross, the handmade candles, a file of research papers. But mainly the leaving was a private gesture: unobserved and un-narrated, intelligible to the leave-taker only. The objects resisted the narratives that effortlessly spin out from inherited jewelry or baby shoes. De Waal’s netsukes are a point of contrast. Pressed by their owner’s painstaking research, the netsukes reveal a riveting story: collected by gay aesthete relatives in Weimar Germany, nearly stolen by Nazis, hidden by a maid, and inherited by an uncle with a taste for Orientalism. A trail of crumbs leads de Waal to a rich and tragic narrative, whereas Hott’s collection coheres into nothing.

The Archive Room gains little coherence from theoretical analyses of collecting. Baudrillard’s The System of Objects, the works of Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones on collecting and anal eroticism, Susan Stewart’s On Longing—all offer insights but exclude the assemblies of bric-a-brac that accumulate on their own, bidden by the will of a group rather than a single agent. The motley objects left at a shrine, for instance, the reams of flowers for Princess Di, the mountains of stuffed animals for the children at Sandy Hook, the sidewalk memorial for a gang victim—these “collections” have no theorist. The number of collectors and their anonymity disqualifies The Archive Room from a true collection, and even if it didn’t, the objects themselves, so many of which are broken, used, or of the earth, teeter toward a hoard. Photos of The Archive Room suggest the flat of Plyushkin, the character in Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls from which Russians take their epithet for compulsive hoarders. The motley nature of Plyushkin’s collections—“scraps” and “shards” and “rags”—makes clear that he is not a discerning collector but rather a peevish eccentric.6

More important than the materiality of the objects is the fact that they were given rather than kept. The objects in The Archive Room speak uniquely of disinvestment rather than acquisition, of gifting rather than collecting. Western culture emphasizes the latter, orienting itself around buying and birthing rather than shedding and dying. Gardening is apt to conjure images of planting, not of pruning, and art is understood as a process of making, although it is often one of subtracting. Americans acquire objects with ease, but require coaching to “purge.” To keep something has the whiff of thrift and prudence, to relinquish invokes the possibility of regret or guilt. The material and psychic charge of a once-important thing often supersedes the practicality of discarding it. Hott’s project—to make sense of a cache of gifts—thrusts this cultural tic in the spotlight.

Lewis Hyde, the celebrated author of The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World, was a Headlands artist in residence. In the book—a manifesto for gift giving—Hyde describes the various types of gifts. He isolates a specific class of gifts as “threshold gifts” or “gifts of passage.”7 Gifts of passage mark transitional moments such as birth, graduation, or death, and their exchange is typically governed by cultural traditions. All gifts of passage mark change; the threshold gift, Hyde writes, is a “guardian or marker or catalyst” of ends and beginnings, a “companion to transformation.”8

Indeed, the offerings accumulated in The Archive Room are the residue of a series of individual transformations: the residency was over, something changed or developed during its term, the leave-taking was a moment worth marking. The artists shed a bit of themselves before departure, as if to materialize a transformation eked out over a few months of unstructured time. Headlands is one of few artist residencies that demands nothing of its residents: no required talk or exhibition or artwork to produce. In its ideal, a Headlands residency is a pause of reflection, a restorative interim. (Artists warn each other that they might take many naps.) The Archive Room filled up with things because the residency experience—empty space and time—produces the surplus of gratitude that draws forth a gift.

As Hott began sorting and organizing the archive objects, she looked for filial lines and resemblances. She seems to have been enlivened by the objects’ opacity, attracted to their muteness where others might be repelled. It is an exquisite match between artist and material. Much of Hott’s past work is precisely about the gauntlet of extracting meaning from topics that flaunt their scope and disciplinary amorphousness: nightfall, whales, electric light. For Hott, attempts at mastery are fragmented and impartial before they even begin, and research becomes a Sisyphean performance.

Carrie Hott, The Key Room, 2016. Commissioned by Headlands Center for the Arts, Marin Headlands, California. Photo courtesy the artist.

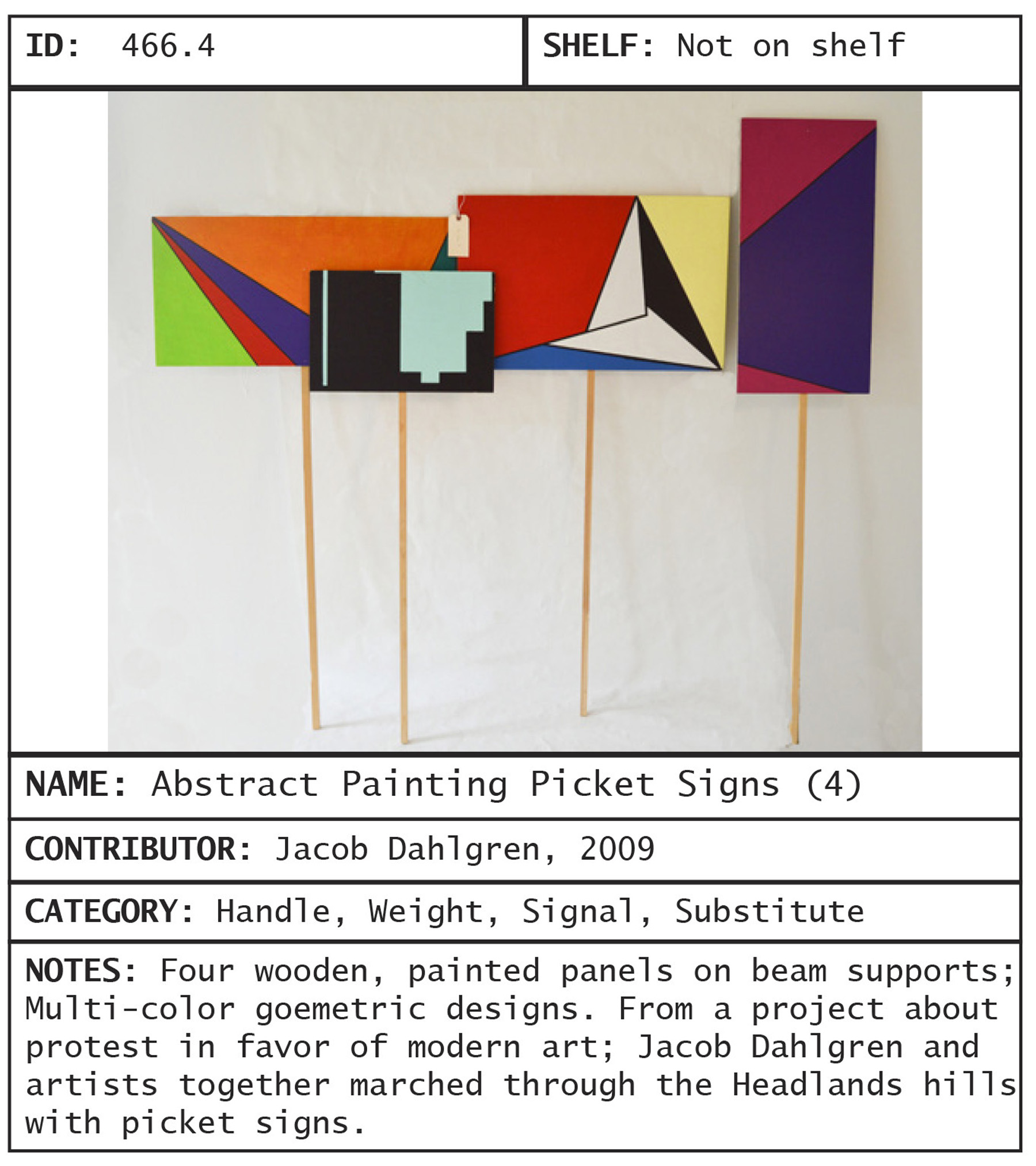

In the case of The Archive Room, Hott invented an idiosyncratic taxonomy that suits the motley nature of the collection. Her categories—Weight, Substitute, Light, Container, and many others—are whimsical and playful.

The category Provision, for instance, includes all items related to sustenance, ranging from actual edibles to artist Walter Kitundu’s photo of a Great Blue Heron devouring a gopher. Handle takes in everything with a handle—spoons, hammers, picket signs—and Signal is reserved for items that convey information, such as books and pamphlets. Each item is tagged with multiple categories: a wood ladle the size of an arm belongs in Handle, Provision, Instrument, Weight, and Container, while a paper target, used for gun practice and left by artist Annika von Hausswolff, is part of Feature, Substitute, and Instrument.

Like a book collection sorted by color, Hott manages to organize and not organize at the same time, creating a system that invokes the futility of all systems. She uses the trappings of a professional archivist—neatly labeled manila tags, a detailed numbering system, fastidious organization—but refuses the professional prerogative. She injects what is usually a sober affair with an impish sense of play. Hott said of this phase of the project that she felt like a “bad” archivist, although her transgression was only to tinker with the strictures of categorization.

Carrie Hott, The Key Room (detail of inventory), 2016. Commissioned by Headlands Center for the Arts, Marin Headlands. Photo courtesy the artist.

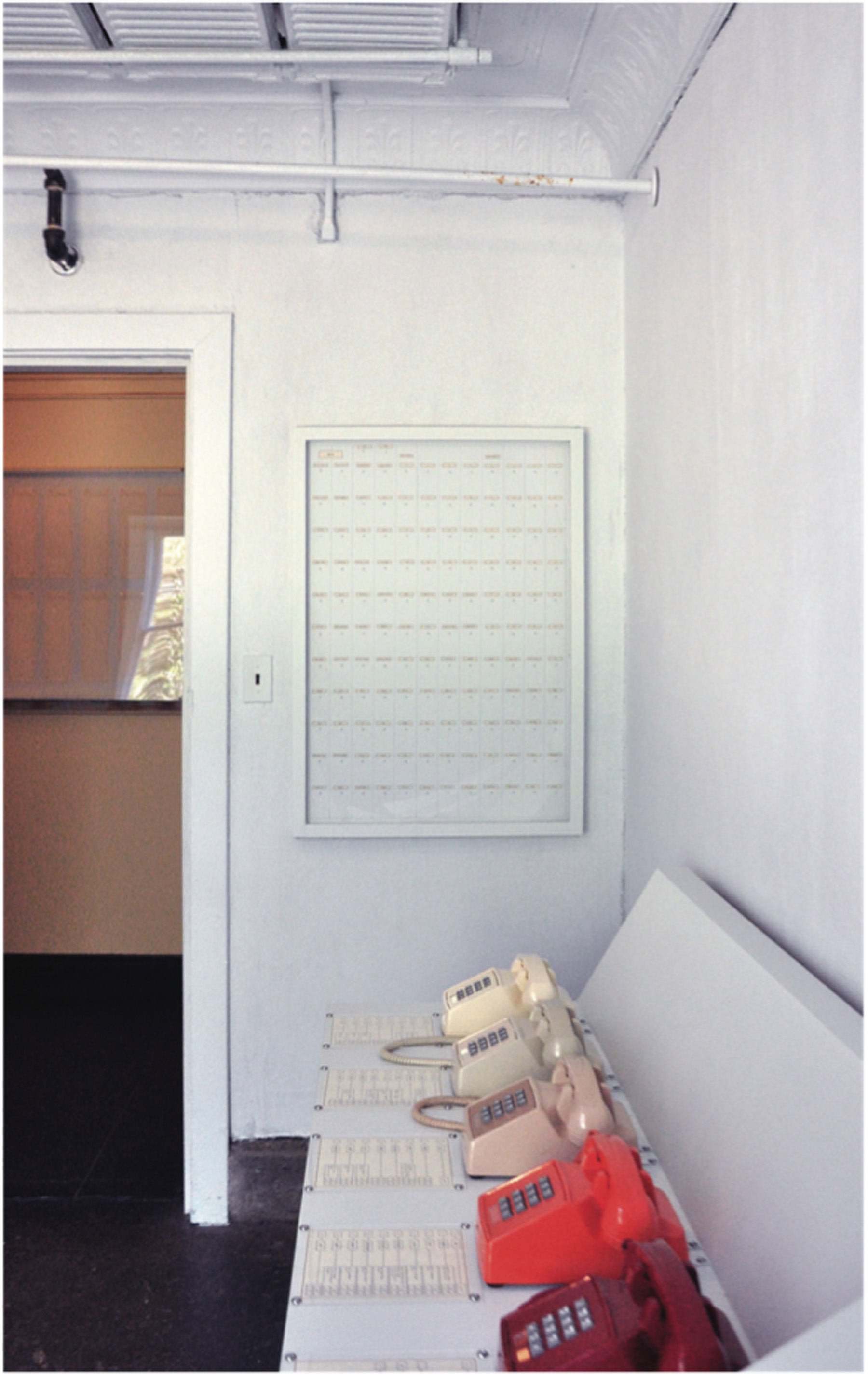

In the final installation, a single categorical group is exhibited in a pristine white cabinet and the featured category rotates over time. Object display, however, is only a small part of the installation. Along another wall of the room are five analog telephones. (The space is nearly entirely white, making the colors of these telephones—shades of khaki and red—seem dense and luscious.) Visitors to the installation lift the receiver to hear former soldiers, park rangers, Headlands staff, and others speaking about the history of Headlands and its site. (Hott recorded some of this material herself; other clips she gathered from various archives.) The room also includes a four-channel video that plays continuously day and night with surveillance-like footage of the surrounding landscape. A series of folio-sized custom binders on a white pedestal supplies an exhaustive catalogue of the archive objects. Another binder, beside the telephones, alludes in its design to a researcher’s notebook and contains clippings and photos about the history of the Headlands. There is a spot in the room for free walking tour pamphlets, which will be produced by Headlands artists in residence, and more material spills into the hallway, where text in glass vitrines lists the hundreds of Headlands alumni and conveys the pedigree of the program.

This assemblage of binders, video, vitrine, objects, pamphlets, and telephones makes for a bewildering number of components, on paper at least. Besides creating an installation about Headlands, Hott has assembled a thorough inventory of the various strategies for delivering information. The superabundance of methodologies seems to be a combination of Hott’s artistic tendency toward surplus and Headlands’ demanding mandate of the installation. In fact, it’s difficult to tell where Hott has been gifted a creative challenge and where she has been freighted with too much responsibility. The Headlands’ original request for proposals solicited “a creative Visitors’ Center of sorts.” Admittedly, the techniques of a traditional visitors’ center are due a makeover, but tasking conceptual artists with didacticism tends to split the difference: the artwork is neither conceptually elegant nor does it deliver information effectively.

Carrie Hott, The Key Room (detail), 2016. Commissioned by Headlands Center for the Arts, Marin Headlands. Photo courtesy Headlands Center for the Arts.

Hott knowingly toes this line. Her clever solution is to undermine her own claim to knowledge, using each of the installation components to suggest the uncertainty of knowing anything at all. Hott reveals her hand over and over, from the archive categories that have no categorical imperative to the walking tours designed by artists. Her knowledge claim is vulnerable and fraught. One last component of the installation makes this particularly clear. A plain plywood board is lined with a grid; each cell contains a nail and a label. The board seems to be the keeping place of an expansive key collection, except that the tiny, meticulous labels have only a tenuous relationship with actual keys. Naked nails await keys to the Pantry, Showers, and Volvo, which seem logical enough, but also the Center, Silence, Reverse Ark, and Fog. Hott invokes the symbolic shorthand for insight and understanding only to teasingly hold it in abeyance. Hott’s title for the project is taken from this unassuming board—The Archive Room will henceforth be known as The Key Room. The title is a tease; there is plenty to amuse and inform, but there are no keys in The Key Room.

Headlands is usually described as the happy antithesis of its military history. Yet the center and its past are bound by a single through-line. An artist brooding over a new project is not unlike a boy in uniform scanning the ocean in the wee hours of the night. Artists at Headlands’ cultivate alertness to the quiet indicators that something new is materializing. They use their time to clear room for what hasn’t yet appeared. Headland’s founders, the soldiers that preceded them, the hundreds of artists who quiet their minds in these buildings—all are tuned in, listening for a signal from the future. Hott’s The Key Room refuses to supply the keys, but generously assumes they will arrive.

Sasha Archibald is a writer and curator in Los Angeles. Her essays have been published in The Believer, East of Borneo, Modern Painters, Los Angeles Review of Books, Rhizome, and several museum exhibition catalogs, and she is an editor-at-large and frequent contributor to Cabinet. She works at the Los Angeles arts non-profit Clockshop.