The modern individual is, above all else, a mobile human being.

–Richard Sennett, Flesh and Stone: The Body and the City in Western Civilization

On October 1, 2007, Sierra Brown lowered herself into the icy waters of the Pacific Ocean at the Port of Los Angeles in San Pedro and embarked on an eleven-mile swim, making her way to a weekly art class at California State University, Long Beach. navigating cargo ships, powerful currents, and the pungent smell of diesel fumes, Brown’s commute lasted six hours and thirty- seven minutes.

Over seven consecutive Mondays, Brown utilized various modes of self-propulsion to transport herself from her home to the university. She cycled, rollerbladed, ran while wearing a polar bear suit, rode a surfboard, Razor scootered, sailed, and paddled an antique swan boat while dressed in Victorian attire. Brown’s Supercommute stages a humorous and pointed critique of our dependency on oil-based transit and the dominant cultural paradigm that the fastest method of traveling from point A to B is always the most desirable. Brown’s adoption of the vernacular of competitive sports and the injuries, mental anguish, and near-misses she sustained en route, demonstrate that commuting without a car in Southern California is not merely an adventure, but an exercise in endurance—an extreme sport.1

Sierra Brown, Supercommute, 2007. Photo: © Ron Stewart Pictures

Nowhere, perhaps, has the automobile so dominated the commuter experience than in Southern California. Freeways connecting urban centers with suburbs combine with a regional mythology of spatial freedom to produce a uniquely car-centered culture. The banal landscapes of Southern California have influenced the work of many of the region’s artists since the 1950s. Recently, however, the Southland has witnessed a series of notable art works focused on the act of commuting itself. By exploring a selection here, I will look at how these projects relate to earlier postwar works and discuss what they reveal about the experience of commuting in Southern California today.

Sierra Brown’s epic non-motorized commuting is paralleled by the daily experiences of Southern Californians who have some of the longest commutes in the United States. The average Angeleno spends 368 hours per year, or the equivalent of fifteen 24-hour days commuting to and from work.2 California ranks fifth in the United States for “extreme commutes”—a commute lasting ninety minutes or more, one-way. In the Southland, this phenomenon is often the byproduct of mass migration to the exurbs of the Inland Empire as citizens in search of affordable housing traverse “several weather zones—from the edge of the Mojave Desert to the Pacific Ocean.”3

A little further south, in Tijuana, more than 50,000 Mexicans, U.S. citizens, and permanent legal residents —who are priced out of the Southern California housing market—cross the U.S.-Mexico border to commute to work in San Diego every day. It takes two to four hours during peak traffic to pass through the San Ysidro and otay Mesa Ports of Entry. At a distance of fifteen miles, the early morning drive from Tijuana to San Diego is perhaps the world’s longest short commute.4

The negative health effects of commuting are well documented and include high blood pressure, musculoskeletal disorders, asthma, heart disease, and even damage to reproductive faculties. The associated stress, isolation, and family separation involved in long distance commutes have been linked to family breakdown and drug addiction in the Southern Californian bedroom communities of Lancaster and Palmdale in the Antelope Valley.5

If daily life in Southern California is defined by extreme commuting, the automobile is not entirely responsible. The provision of interurban and street railways in Los Angeles in the late 19th and early 20th centuries provided impetus for the development of suburbs in outlying areas, and laid the groundwork for the horizontal character of the region.6 Nevertheless, growing automobile usage accelerated the earlier process of decentralization. By the late 1930s, the decline of public transit, combined with the lobbying efforts of state boosters and key interest groups such as the Automobile Club, prompted Los Angeles to develop a regional transportation plan that would form the basis for “the first and largest metropolitan freeway system in the United States.”7 By the 1950s, as federal aid was made available for postwar urban transportation projects, the freeway construction boom began. Combined with a postwar utopian vision of suburban domesticity, this paved the way for the landscape of sprawling infrastructure that is Southern California today.

The everyday experience of the distinctive Southern California cityscape that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s influenced a generation of artists. Ed Ruscha’s dramatic diagonal compositions celebrating roadside architecture and signs such as Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas (1963), and his evocative monosyllabic word works, for example Boss (1961), were influenced by the street iconography the artist would see en route during his frequent trips back and forth between Los Angeles and Oklahoma City. Ruscha’s serial typologies of mundane Los Angeles vernacular architecture such as Some Los Angeles Apartments (1965), Every Building on Sunset Strip (1966), and Thirty Four Parking Lots in Los Angeles (1966) chronicle the repetitious, banal landscapes of Southern California, while the durational structure of the book format serves to mimic the trajectory of the highway.8 Art historian Andrew Perchuk argues that the “insistent seriality in Ruscha’s work, the sameness and difference together…is predicated on a phenomenological experience of the landscape from the perspective of a driver,”9 where the city is apprehended as a series of moving images that “are briefly framed, erased, reconstructed, and forgotten.”10 Mimicking the scanning gaze of the driver, Ruscha’s depiction of Every Building on Sunset Strip, for example, was achieved by mounting a camera on a pick-up truck and driving it the length of the boulevard to achieve a continuous recording of each facade on either side of the street.11

John Baldessari, The Backs Of All The Trucks Passed While Driving From Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, Calif. Sunday 20 Jan. 63, 1963. 32 color photographs from 35mm slides, 60 x 42.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

This monotony of suburbia and non-descript cityscapes, often shot from the car, became a subject for John Baldessari in his phototext works of the mid 1960s. In works such as Looking East on 4th and C… (1967-68), Baldessari attempts to dismantle received ideas of “correct” photographic composition by taking random snapshots of national City from his Volkswagon bus. In an early photomontage work, The Back of All the Trucks Passed While Driving From Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, Calif. Sunday 20 Jan. 63 (1963), Baldessari photographed the backs of 32 trucks through the windshield of his car, and then displayed them side by side as a series of slides. As with Ruscha’s books, the serial arrangement of photographs suggests an experience of duration and ensures that every subtle variation in the framed landscapes is amplified. Thus, the gaze of the viewer parallels the restless eye of the bored Southern California commuter who scans the road in search of visual stimuli to disrupt an otherwise uneventful and scripted journey.

If Ruscha’s taxonomy and Baldessari’s incidental encounters present a deadpan navigation of the Los Angeles landscape via car, Dutch-born artist Bas Jan Ader’s In Search of the Miraculous (One Night in Los Angeles) (1973) adopts a tragic-comic approach to the existential experience of dislocation in the Southern Californian cityscape. Fourteen photographs document Jan Ader’s urban wanderings through an empty landscape of freeways, underpasses, and suburban houses as the artist makes his way from a Los Angeles valley to the ocean. Art historian Thomas Crow notes, “the evocations of place and its mythology are manifold: the freeway (along which walking is a criminal offence), the nocturnal crime scenes of Hollywood film noir; the Pacific shore as the stopping point of westward migration.”12 The lone figure of Jan Ader, dwarfed in the landscape, recalls German romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s depictions of contemplative figures silhouetted against mists, trees and night skies. A handwritten inscription of lyrics to the 1957 Coasters hit “Searchin’” overlies Jan Ader’s photographs. The rhythmic, repetitive nature of the song (“Yeh. I’ve been searchin. I’ve been searchin. oh yeh…”) reinforces the durational quality of the piece, and also comically underlines the artist’s seemingly pointless and unresolved quest.

Bas Jan Ader, In Search of the Miraculous (One Night in Los Angeles), 1973 (detail). Courtesy of the Bas Jan Ader Estate and Patrick Painter Editions.

Whether these key works by postwar artists Ruscha, Baldessari and Jan Ader act as a critique of the new sprawling suburban cityscape is ambiguous— perhaps intentionally so. The works have an “aura of vacancy and a palpable yearning for meaning,”13 a quality that commentators such as Los Angeles-based curator Howard Fox have suggested is present in much of Southern California’s seminal art. Certainly, the artists’ focus on urban banality and the effects of this new urban model on everyday experience, along with the subtle humor of these works, suggests a latent critique of Los Angeles boosterism. Concurrently, across the Atlantic ocean French sociologist and philosopher Henri Lefebvre was crafting a searing indictment of the “new time space relationships that had resulted from the urban process of suburbanization and the need for commuting.”14 In his 1968 publication La vie quotidienne dans le monde moderne (Everyday Life in the Modern World) he refers to commuting as “compulsive time,” arguing “if the hours of days, weeks, months and years are classed in three categories, pledged time (professional work), free time (leisure) and compulsive time (the various demands other than work such as transport, official formalities, etc), it will become apparent that compulsive time increases at a greater rate than leisure time.”15 Lefebvre suggests, in a view shared by his sometime collaborators the Situationist International, that as French postwar reconstruction and rapid modernization ushered in a new culture of consumption, the growing unpaid limbo of the commute provided yet another example of how everyday life was now lived according to the rhythm of capital.

In 1959, Guy Debord, leader of the Situationist International, penned the text “Situationist Thesis on Traffic.” Partially satirizing the functionalism of the Athens Charter,16 Debord critiques the privileged place afforded the private automobile by French postwar city planners by arguing that the car is a “supreme good of an alienated life and the essential product of the capitalist market.”17 Paris too witnessed a massive spatial reorganization in the 1950s and ‘60s with the installation of expressways, the orbital freeway, parking lots, and the growth of suburbs. For the Situationists, the emergence and growth of the commute by private automobile signaled the dissolution of traditional city life. In a 1964 issue of their journal Internationale Situationniste, the group reproduced a “core garage” urban planning project by Januz Deryng in which Deryng proposed locating massive underground automobile garages beneath Paris. The Internationale Situationniste reproduced this example of so-called cutting-edge urbanism as a critique of urban planners “servile submission to the pretended logic of the private car.”18

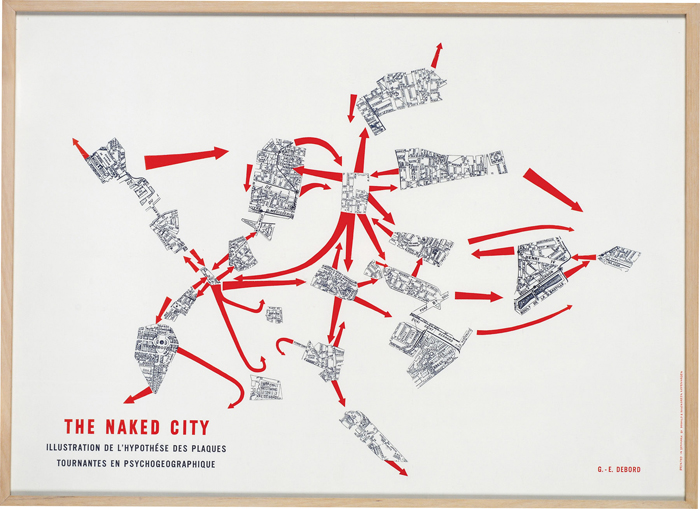

Guy Debord, The Naked City, 1957. Color psychogeographical map on paper, 13 x 18 inches. Musee d’art Moderne et contemporain de Strasbourg Cabinet d’art Graphique. Photo: Mathieu Bertola. © Alice Debord, 2004.

Commuting time, claims Debord in “Situationist Thesis on Traffic,” is “as Le Corbusier rightly pointed out surplus labor which correspondingly reduces the amount of “free time,” therefore “we must replace travel as an adjunct to work with travel as a pleasure.”19 Indeed, the Situationists’ non-utilitarian wandering in urban space, the dérive, can be viewed as a creative alternative to, and a rejection of, the repetitive routine of the commute. A practice of aimless drift where “one or more persons…drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there,”20 the dérive transgresses the normative impulses of a capitalist society: consumption and production. It offers opportunities for urban improvisation, unscripted behavior, and unplanned interactions with others.

In a similarly open-ended psychogeographic exploration, Vincent Ramos’s research-based project The Commuter (2008) traces a selection of his family’s former commute routes around Los Angeles over a 20-year period from the mid-‘50s to the mid-‘70s.21 Presented as an archive of found objects, period radio recordings and a map of photographs and intersecting itineraries threaded together with colored string, Ramos’s project draws visual parallels with the Situationists’ maps such as Naked City (1958) and Ruscha’s and Baldessari’s serial portraits of urban banality. Ramos’s more personalized approach reveals the intersections of the working-class Chicano experience with the important economic development of the aerospace industry, the sinister history of the Manson murders, and the disappearance and reconfiguration of certain Los Angeles landmarks. Through this recovery of a lost narrative, the project emphasizes the vital role that the Chicano community played in the history of the region.

Vincent Ramos, The Commuter, 2008. Installation view. Photo: Charchi Stinson.

Ramos established the stationary points of home and work through informal interviews with family and family friends and by consulting personal papers and public archives. Piecing together the physical route between those two points became a disorientating speculative exercise, frustrated by the fallibility of memory and the shifting geography of a city that “has constantly erased the physical traces of previous urbanisms.”22 Like the dérive, Ramos’s journeys through Los Angeles, guided by his research, became a way to get lost and to encounter the city anew. Whereas the Situationists’ cartography depicts Paris as a discontinuous conurbation of quarters that have withstood the homogenizing effects of capitalism, highlighting spaces of sociability and unexpected encounter, Ramos’s drift is part time-travel, part archeological dig.23

Vincent Ramos, The Commuter, 2008. Installation view. Photo: Charchi Stinson.

The Commuter underlines the physical impossibility of literally staging a peripatetic drift across a modern city like Los Angeles, where nearly one half of city land is devoted to car-only environments. Roving across the region privately in his car, Ramos suggests that the viability of the dérive is dependent on a specific historic urban model. In contrast to its European counterparts, Southern California evolved into a conurbation without a central core, where pedestrian encounters are increasingly superseded by mediated exchanges in cars, via cell phone conversations, texting, and email.

In contrast to Ruscha and Baldessari’s depictions of Southern California’s mass-produced urban infrastructure as seen from the road, it is the trajectory of the car that becomes dominant in Ramos’s work. The stationary spaces of home and work anchor an experience of perpetual flux and movement. The Commuter’s map of intersecting routes embodies cultural theorist and urbanist Paul Virilio’s predictions of a society no longer of “sedentarization, but one of passage: no longer a nomadic society, in the sense of the great nomadic drifts, but one concentrated in the vector of transportation.”24 Virilio argues that instantaneous globalized information flows are leading to a warping of time and space where the global and the local begin to collapse into one another and history starts to unfold within a one-time system: global time. He refers to a “post-automobile society” in which electronic mobility effectuates a new world order of simultaneity and the interchangeability of spaces. Ramos’s installation suggests this encroaching possibility by including radio programs from the 1960s and ‘70s. The presence of media devices today is key to the Southern Californian commuter’s experience. With advanced communication technologies and 24/7 news networks, the public world of events is interjected into the private space of the car via radio, cell phone, television and increasingly, the Internet accessed by way of Blackberries and iPhones. Distant locations are telescoped in space and time. A commuter utterly immobilized on a congested freeway is still located within the vectors of the speed of global information.

Elana Mann, Shifting, 2008. Installation views. Photo: Elana Mann.

Elana Mann, Shifting, 2008. Installation views. Photo: Elana Mann.

This experience of global-local compression is probed by Elana Mann in her project Shifting (2008), a CD featuring 29 minutes of recorded commentary by 12 north American commuters in Iraq and Los Angeles interspersed with field recordings such as the ethereal whistle of a subway train passing through an underground tunnel and the crunch of bicycle wheels over an uneven road.

As described by one of Shifting’s contributors, the wandering gaze of a Southland commuter as she spaces out or surveys fellow travelers in their cars is paralleled by an American soldier’s account of commuting in Iraq and his heightened state of observation, in which he absorbs and responds to the environment rapidly, constantly alert for potential threats and dangers: “It’s a constant jumping of the eyes, and the orientation of the weapon. … Staying as low as you can. Sizing up the vehicles. Sizing up the streets. Sizing up the buildings.”25 Recordings of Los Angeles traffic reports are juxtaposed with the comments of a U.S. soldier who explains how deadly traffic congestion in Iraq can be and how he is trained to snake back and forth across the road to avoid being targeted in an immobile vehicle.

While Ruscha, Baldessari, and Jan Ader seem, in part, to have been responding to Los Angeles as a city and cultural site, Mann’s piece considers Los Angeles in relation to another remote geographical and cultural location. Juxtaposing audio selections, such as a field recording of a commuter filling up his or her car with gas with the voices of Iraqi and Angeleno commuters, Mann adeptly highlights what links Los Angeles and Iraq in a globally networked system of commerce and geopolitical decision-making.

Commentaries included in Shifting also reference gendered, racial, and class-based landscapes of the commuter in Los Angeles and Iraq. Public transit is perhaps one of the few spaces in Southern California where civil society exists, even if only as an alienated possibility. In principle, public transportation is accessible to all. However, demographics of public transit users very clearly suggest the uneven and disparate access to transportation in the region, where the expense of a private car is prohibitive to many. One commuter in the piece, journeying to the University of California, Los Angeles, comments on the social stratification of the bus system. She describes a parallel commuting world of aged veterans en route to the VA Hospital and working-class women of color traveling to service jobs in the Westside homes of Brentwood and Bel Air. Mass transit in Southern California may offer the promise of public domain—a space of interaction where exchanges between different social groups, which strengthens social cohesion, is not only possible but actually occurs—but in reality it often simply serves to demonstrate the inscription of social inequities in urban space.26

If Mann’s project suggests that the act of commuting in Southern California replicates society’s inequalities or makes commuters unwitting accomplices in a distant war, it does not address strategies to transgress that reality. When the Situationists practiced the dérive it was part of a larger, far-reaching project to change the structure of society by liberating oneself from the stultifying repetitive acts of capitalist society, such as the commute. A new form of transport had to be created that would make travel a joyful experience. Debord envisioned a time when the automobile would be defunct; he even suggested that one-man helicopters (being tested at the time by U.S. military) might be the way of the future.27 While the environmental implications of this prediction would be disastrous, there are numerous contemporary efforts to promote alternative commuting practices in the Southern California region, ranging from Critical Mass’s monthly events held in cities around the world in which bicyclists gather to collectively ride around town, to the “ArroyoFest Freeway Walk and Bike Ride” hosted by occidental College on June 15, 2003, during which the 110 freeway was closed to motor vehicles.

For Henri Lefebvre, everyday life reproduced an existing culture of alienation, but also served as a space of possible transformation. Lefebvre perceived daily life as offering moments of potential abrogation, and, in his later writings, a kind of creative power that could be harnessed on occasion. Might the everyday praxis of automotive commuting also unfold as an insurgent action, in addition to replicating existing economic and social structures?

In 2004, Swedish artist Mans Wrange attempted to harness commuters’ “unproductive” transit time with his project for inSite, the periodic international artist residency project based at the U.S.-Mexico border in San Diego and Tijuana. The artist proposed to collectively marshal peoples’ travel time by appropriating the model of distributed computing—the process by which a computer program is split into parts that run simultaneously on multiple computers communicating over a network. Wrange hoped to enable commuters to use that time for a mutually beneficial, creative, and socially focused purpose. The challenge of defining a sufficiently motivating social purpose that commuters would be willing to collectively coalesce around was one important factor in the failure of Wrange’s proposal.28 More significant, however, was the fact that, contrary to Wrange’s initial assumption, the artist discovered that commuters did not have any “available” time to re-direct, even if the activity was potentially socially beneficial, creative, and fulfilling.

Sierra Brown, Supercommute, 2007. Photo: © Ron Stewart Pictures.

The film Ellie Parker (2005)29 provides us with clues as to why Wrange’s community of commuters might have been unable to participate. In a key scene, the actress Ellie Parker, played by Naomi Watts, is commuting in her car from one audition to another. Over the course of her commute, we witness Ellie rehearsing for her next audition, applying make-up, changing clothes, talking to her agent about a part and arguing with her boyfriend on her cell phone, and singing along to the radio. All of this frenetic activity takes place in the confines of her car as she shuttles along Los Angeles freeways. This is not an unfamiliar scenario to anyone who has spent time driving in that city. A diverse spectrum of activity takes place in the space-time of the automobile commute. This can be read as an example of Michel de Certeau’s conception of temporal tactics of resistance that he lays out in his influential book L’invention du Quotidien Vol. 1, Arts de faire (The Practice of Everyday Life) (1980). De Certeau contrasts the ad hoc, temporal tactics of everyday resistance such as la perruque—worker’s disguising their private work as that of their employers—or “poaching”—the clandestine use of resources that one does not own—or the inventiveness of everyday lifestyles and dress with the overarching strategies of institutionalized power. Lefebvre’s “constrained time” is transformed by the multi-tasking Southern California commuter into a cushion of time and space to play, communicate, reflect or fulfill pressing tasks.

If key works by postwar artists Ruscha, Baldessari and Jan Ader were influenced by their experiences of Southern California’s mass-produced, car-centric landscapes, and the Situationists concurrently rejected and resisted the mass transformation of their city in accordance with the logic of the private car and capitalist imperatives, many of the contemporary explorations of the act of commuting here described bring these two positions into a critical relationship. Mann’s, Ramos’s, and Brown’s works explore the landscape of Southern California via the mobile act of commuting, and yet each artist practices the act of commuting as a form of critique. Thus, these projects suggest that for the Southern California commuter in particular “the political…is hidden in the everyday, exactly where it is most obvious, in the contradictions of lived experience; in the most banal and repetitive gestures of everyday life: the commute, the errand, the appointment. It is in the midst of the utterly ordinary, in the space where the dominant relations of production are tirelessly and relentlessly reproduced, that we must look for utopian and political aspirations to crystallize.”30

Donna Conwell is project specialist in the Department of Architecture and Contemporary Art at the Getty Research Institute and adjunct faculty of the Masters of Public Art Studies at the University of Southern California.