Cang Xin, Duan Yingmei, Gao Yang, Ma Liuming, Ma Zhongren, Wang Shihua, Zhang Binbin, Zhang Huan, Zhu Ming, and Zuoxiao Zuzhou, To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain, 1995. Performance, Miaofeng Mountain, near Beijing. Color video, silent, 6:03 min. Courtesy of Zhang Huan.

And he [Wang Jianwei] said, “Why would you want to do this show?” And I said, “You know, I feel like these artists have been living in a zoo, and the zoo is China.” And he said, then, to let them out of their cages.

—Alexandra Munroe1

An empty cage is not, by itself, reality.

—Huang Yong Ping, Vomit Bag, 2017

In the most famous images of the Tiananmen Square Massacre of June 4, 1989, a lone man stands in the way of a column of tanks. As the lead tank tries to go around, he moves to block it again. The man is wearing a white dress shirt and holding two bags, as if he’s coming home from the store or the gym and just happened to get in history’s way. It is a powerful picture of defiance. Looking at it on the thirtieth anniversary of the massacre, one might almost forget that many of the hundreds and probably thousands of demonstrators killed that day were crushed to a pulp beneath these same tanks, perhaps even the anonymous Tank Man. When the teargas cleared, the square was littered with charred army vehicles, mangled bicycles, and the shot and maimed bodies of students—evidence of events far bloodier than the Tank Man story suggests.

Huang Yong Ping, Theater of the World/Artist’s Gesture, 1993/2017, presented devoid of living animals, and The Bridge/Artist’s Gesture, presented devoid of figurines and living animals. © Huang Yong Ping. All works courtesy of the artist. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2017.

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art installation of Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World begins with a parody of this more violent Tiananmen iconography. Wang Xingwei’s painting New Beijing (2001) adapts another famous photo from 1989, in which two fallen students are being rushed to the hospital on the back of a rickshaw. In Wang’s painting, the demonstrators are replaced by two emperor penguins, their wounds trickling red onto their white feathers.2 A thoughtful viewer might expect the artist’s choice of these animals to have specific meaning or symbolism. There is none to be found. An image meant to give a concrete shape to tragedy has been rendered as a macabre non-sequitur in progressive history. In Wang’s view, however, such a rupture better depicts the oppressive political logic of modern China. Like the Communist Party, which barely denies the events of June 4, 1989, yet encourages everyone to focus on the prosperity of the ensuing thirty years, Wang’s transposition renders the massacre as having less than human costs. At the same time, this painting hints at the uniquely brutal strain of Chinese contemporary art—involving often violent actions in which live birds, fish, dogs, livestock, and other animals stand in for human victims—that emerged from the social foment leading to, and unavoidable after, Tiananmen. Wang’s euphemism only heightens a sense of realpolitik that often goes unremarked when the victims are only human. Or, more to the point, the painting upends the tropes that attend images of “suffering” consumed in the West, which mostly serve to trigger the familiar routines of expressions of empathy followed by forgetting.3 Such substitution is also a strategy to describe the brutality of a regime that has only tightened its grip since 1989, and thus cannot be criticized directly.

New Beijing is a massive history painting, and at SFMOMA, it is difficult to get a full view. Back far enough away from the canvas and you’ll hit the two interlocking animal-shaped, wood and wire cages that dominate the first room: Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World (1993) and The Bridge (1995). The latter work, roughly shaped like a snake, arcs over the tortoise-shell geometry of the former, a central arena lined with trapezoidal compartments. As designed by the artist, both cages are meant to teem with live animals: snakes and turtles shuffling under the sunlamps of The Bridge while scorpions, geckos, and an assortment of insects fight to the death below.

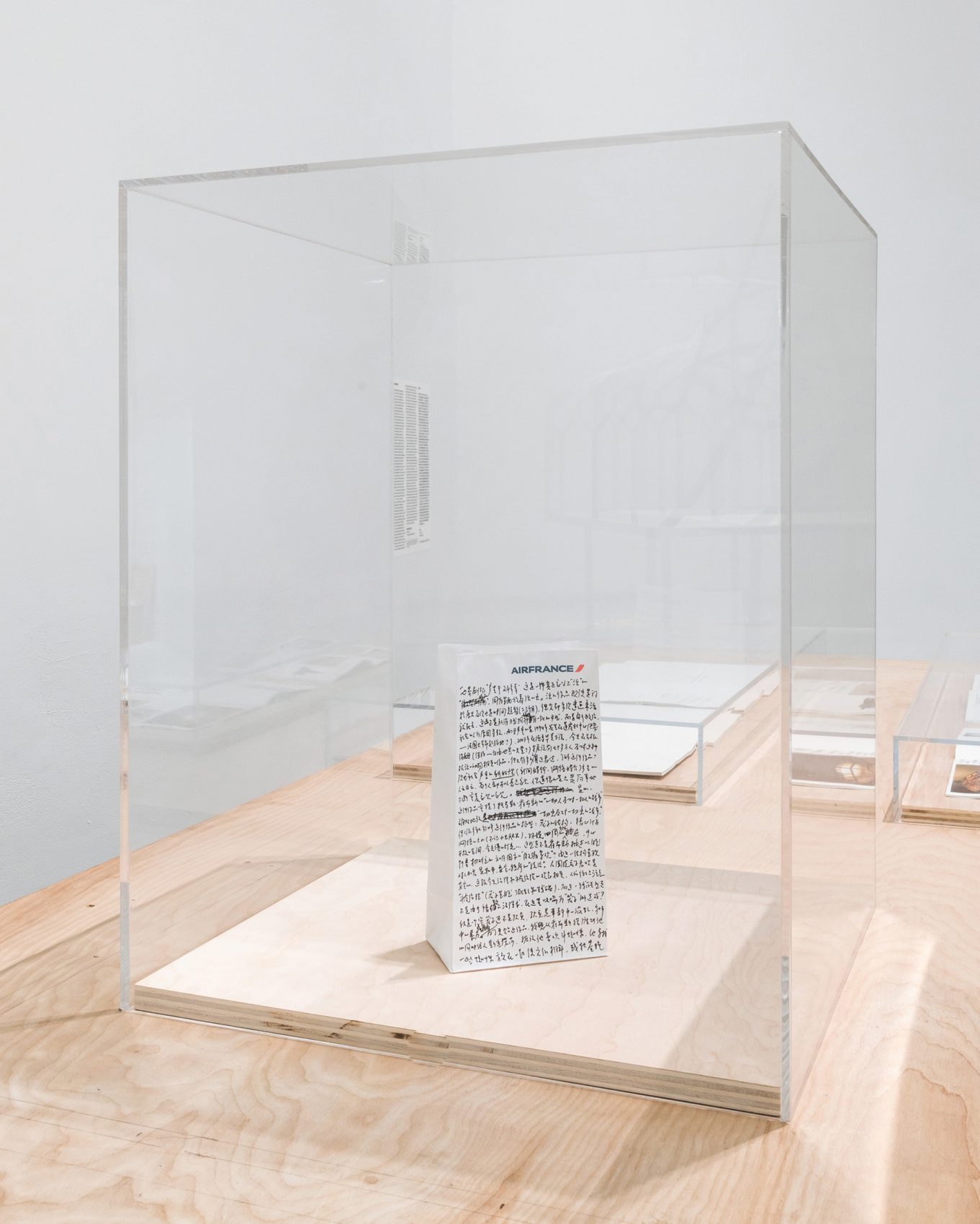

The exhibition borrows its subtitle from Huang’s work. Yet, at SFMOMA, the cages are empty and clean—not a scab of blood or exoskeleton or feces, no evidence of a struggle. Huang’s installation was one of three works appearing in censored form in Theater of the World at SFMOMA, following a decision taken shortly before the opening of its original installation at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Huang’s response to the controversy is displayed in a vitrine nearby. He wrote the work, titled Vomit Bag (2017), on a transatlantic flight on the most appropriate piece of paper at hand.4 The text appears in translation on a wall label. There is another text, too, in the institution’s voice: “When the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, was planning this exhibition in 2017, it received repeated threats of violence in response to the role of animals in the creation of this artwork.” The label then describes how the Guggenheim, in consultation with the artist, decided to represent this work as an empty set of cages. It concludes: “SFMOMA has chosen to replicate these modifications in order to acknowledge the fact that the tension between political activism and animal rights is now part of the history of the artwork.”

The exhibition Theater of the World thus begins as if “the whole world is watching,” recalling how the brutality and realpolitik of Chinese communist life suffered a bout of self-consciousness, even conscience, when faced with its own ideals. Huang based Theater of the World partly on his reading of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) and its antecedent, Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon (1791). The insect arena is also a panopticon, inviting the public to witness these animals’ unsentimental battles and deaths. Post 1989, the idea of the witness flips into its more cynical contemporary sense, where these four-, six-, and eight-legged Manichean fighters are subject to a more sinister gaze—that of a prison or a zoo. Theater of the World begins surveilling Chinese art at a point where the overt radicalism of the 1980s diverged into more arcane and more mainstream forms and ends with the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, where Ai Weiwei’s involvement in the design of the Bird’s Nest stadium, and thus his tacit artwashing of slum clearance, represents the pinnacle of what an artist in accord with the Chinese Communist Party could accomplish. Meanwhile, artists who had grown hopeful that art might be a place to make explicit political statements retreated into coded, symbolic forms; art historical overtures; and sometimes generally zany behavior, all with only a notional political bite. The margins still exist, and the Chinese state doesn’t care too much if a few artists decide to live there, so long as they behave when they visit the public square. It helps, too, when their messages are discreet enough to pass as fine art.

Wang Xingwei, New Beijing, 2001. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 in. © Wang Xingwei. Courtesy of M+ Sigg Collection.

Theater of the World includes a pair of videos in this cryptic vein by Zhang Peili. The label notes that 30 x 30 (1988) is considered the “first video artwork produced in China,” and it reestablished the durational, almost non-narrative mode common to early video work in other countries, from the United States to Brazil to Japan. In 30 x 30, the artist shatters and repairs a mirror, again and again. In Document on Hygiene No. 3 (1991), Zhang is pictured gently washing and rewashing a live chicken in a basin of water over the course of nearly half an hour. It may be too much to say that the differences between these two works exemplify a movement from more overtly aggressive, even masochistic symbolic acts, like arranging broken glass, to the symbolic stubbornness of a “passive-aggressive” care regimen. Yet the latter piece, made post-Tiananmen, seems to register a simmering, compulsive absurdity that has no outlet, as if when the choice is between open rebellion and total compliance, one washes the chicken as required—only way too well.

Huang Yong Ping, Vomit Bag/Artist’s Gesture, 2017. Statement on Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, created in response to the controversy surrounding the Guggenheim’s presentation of the artist’s Theater of the World (1993). Ink on airplane sick bag, signed and dated September 30, 2017; 5 x 9 3/8 in. Courtesy of the artist.

The post-Tiananmen generation of Chinese artists also began to play with a Western idea of the avant-garde—often explicitly, as in the case of the May 1989 exhibition China/Avant-Garde held at the National Art Museum of China, Beijing, and pieces such as Huang Yong Ping’s invocation of Marcel Duchamp—as the Communist Party of China allowed the Chinese avant-garde access to the perks of globalization. These artists’ use of “bodies,” both their own and those of live or dead animals, cites the early performance-based video work from the United States’ avant-garde a full two decades prior. Most notorious is Tom Otterness’s reprehensible Shot Dog Film (1977), in which he killed a dog on camera—an especially sadistic act in a permissive, open-ended context of free expression. But references to food and food animals in the context of social codes also recall Suzanne Lacy’s Learn Where the Meat Comes From (1976) and William Wegman’s early Portapack video works, such as Milk/Floor (1970–71), in which Wegman crawls backwards into the frame while spitting milk onto the floor. One of his dogs then enters from the same direction, lapping up the milk.

William Wegman, Milk/Floor, 1970-71. Black-and-white video, sound, 1:03 min. Courtesy of the artist.

William Wegman, Milk/Floor, 1970-71. Black-and-white video, sound, 1:03 min. Courtesy of the artist.

More than the Euro-American canon, however, this mode of Chinese video art resembles the strategies and risk-taking of video art under Latin American dictatorships. In these circumstances, a dry style of videomaking codes its messages in order to avoid government censors in countries where hunted countercultures had to make room wherever they could. One especially masochistic, bodily example is A Situação (1978), by Geraldo Anhaia Mello, in which the artist drinks himself unconscious by repeatedly toasting the dictator and the social con- ditions in Brazil with small glasses of the cheap cane liquor favored by peasants.5 In China, the situation was both more ambiguous and more clearly defined: as the country grew rich, so did its artists, until “both art and government . . . are aligned with the space of commerce and the market—or ‘development,’” a tacit alliance “which potentially smooths over political frictions.”6 Given such differently liberal opportunities for self-expression, Chinese artists sought to animate other kinds of frictions that can survive this official calm.

Zhang Peili, Document on Hygiene No. 3, 1991. Single-channel video, 24:45 min. Courtesy the artist and Boers-Li Gallery.

Where the ritualistic acts of animalworks (to borrow Meiling Cheng’s term) are concerned, animals not only serve as metaphorical foils for other forms of social conflict but also deflect the controversy evident in their subtexts onto the explicit complexities of human-animal relationships, in terms ranging from worship to torture, light parody to bestiality.7 This “transference” is amply demonstrated by a suite of works by Xu Bing that feature a male pig in rut. The version censored from Theater of the World is a video document titled A Case Study of Transference (1993–4), which shows a boar attempting to mate with a sow in a pen surrounded by human onlookers. The “meat” of the work is not the copulation itself but rather the nonsensical roman type and Chinese ideograms painted all over the male and female pig’s bodies, respectively. Xu invokes transference in the Freudian sense, if barely—but also allegorizes the rubbing-off of cultures that occurs when one mounts the other, mimicked on another level by the transfer of biofluids and genetic material. Indeed, in the most wide-angle transference in this piece, Xu manages to rephrase a serious international tension between two superpowers as a cryptic, even zany artwork. The most controversial element, all things considered, becomes the pigs’ essentially pornographic presentation to an audience. The more troubling question of dominance is deferred.

A Case Study of Transference plays with differences in how animals fit into Chinese versus Western cultures. In an article about the exhibition, critic Ben Davis notes that the “particular sentimental hypersensitivity to animal rights issues” expressed by viewers in the United States “is due to a combination of factors: we have been mostly urbanized for generations, so the animals we encounter on a daily basis are specifically bred as adorable companions. At the same time,” he writes, “we are a gluttonous, fast-food-obsessed, hyper-capitalist country. Any less-than-superficial acquaintance with the conditions of the industrial food production system triggers revulsion.”8 In contrast, Xu was born during the Cultural Revolution and worked for years on a farm; the pre-industrial, husbandry-type relationship to the pigs he recruited for his artwork is partly an extension of seeing, and treating, animals as tools and food. This less sentimental view might seem like abuse or neglect to an audience that prefers its pork processed into as abstract a form as possible. The pigs are mating like pigs do. The ink doesn’t hurt them, and the audience doesn’t embarrass them. “We have to be cautious,” writes Cheng, “in applying Euro-American values such as animal rights and eco-consciousness to China.”9

At the same time, it would be equally problematic to attribute the themes of Chinese animalworks to a kind of underdeveloped, even primitive relationship to animals. Certainly, organizations like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals are a Western luxury. Yet part of Chinese artists’ comfort with using animals as materials is due to a particular sophistication—an obsession with the freshness of food, produce, and other ingredients that makes killing live animals a regular part of preparing food in China, both in restaurants and in the home.10 Nor do animalworks take Chinese values as given. Peng Yu, an artist whose most famous work, Curtain (1999), comprises a tapestry of wriggling, gasping, dying fish and amphibians impaled on wires, points out “the hypocrisy within the Confucian admonition that a gentleman should stay away from the kitchen to avoid witnessing the cruelty of animal killing—which serves one’s stomach and not one’s conscience.”11 Cheng suggests that, rather than a pragmatic callousness toward edible creatures, “Peng’s self-defense seems to suggest that one can fight hypocrisy with shock treatments.”12 With Xu’s snide theater of superpower relations and Peng’s Curtain, which exposes rather than conceals an everyday cruelty, it’s as if the pieces achieve their full potential only after someone gets upset. Sure enough, A Case Study of Transference was censored both in New York and San Francisco. Like the Guggenheim, SFMOMA “left the video documentation in place but turned it off, and the photograph was represented as a blank gray rectangle on the wall.” (The artist also offers a short text in the wall label.) Again, an abstract absence stands in for the disputed use of animals in the work itself.

Ironically, the use of animals had invited threats of bodily harm to the Guggenheim’s (human) staff. The Guggenheim was able to extract itself from that potentially dangerous position. Indeed, as Mel Y. Chen suggests of Xu’s work, it is acceptable for animals to undergo the trials of performance art, but only voluntarily and knowingly—in other words, with the kind of sophisticated consent only humans are known to give. Thus the “bodyworks” by Chris Burden, who variously starved, shot, cut, buried, and otherwise endangered his own body, while controversial, have not occasioned the same outrage. Theater of the World does contain a handful of corollary artworks in which the artists put their own bodies at risk. A screen hanging in the center of the same room that A Case Study of Transference would have occupied displays video documentation of a collaborative performance titled To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain (1995). For this performance, five people strip down, weigh themselves on a scale, then stack their naked bodies into a pile one meter high. A video by Lin Yilin, Safely Maneuvering across Linhe Road (1995), is an exceptionally poetic example. Over the course of half an hour, the artist uses a stack of cinderblocks several meters wide by two meters high by a single block thick to shield himself as he crosses the road at a crosswalk. To move the barrier, he must stack and restack the bricks, moving the back column to the front, again and again, making incremental progress but exhausting himself (and breaking several bricks) in the process. The artist makes it across eventually. The imminent danger from cars and busses was not staged. In fact, the viewer gradually realizes that traffic on Linhe Road goes one way, and that the artist keeps to the exposed side of the wall. Someone could have been killed. At least no non-human animals were involved.

Significantly, Lin’s makeshift barrier consists of construction materials, and what awaits him on the other side of the road is a construction site. The shift to self-inflicted risk can be read as a development beyond the use of dumb animals. This tracks with the parallel assumption that the sophistication of a modernizing and increasingly bourgeois Chinese culture is reflected, among other ways, in their treatment of animals, such as the reclassification of some from food to pets. Mel Y. Chen notes in Animacies that pet ownership has steadily become more popular in China, to the point where in 2006 Beijing introduced a “one family one dog” policy; campaigns to spay and neuter pets echo the rationale of the one-child (now two-child) rule. These shifts also coincide with a push to ban dog meat.13 Yet again, the American reaction is less sophisticated than what prompted it. The anti-animal cruelty petition sent to the Guggenheim, New York, before Theater of the World had had a chance to open bears the xenophobic views of many of the 800,000 signatories, who profess not to be surprised that the Chinese are behind this outrage, while citing the particular cruelty of the Chinese “race.”14 These petitioners, who could see their way to protecting the rights of animals, used these human artists’ “abuse” of animals to justify “lessening” their humanity. Their petition succeeded, partly, by lowering the Chinese artists (and therefore their actions) below the threshold of protected free speech.

Xu Bing, A Case Study of Transference, 1993-94. Performance and video with two live pigs inked with false English and Chinese characters, discarded books, barriers. Installation view, Han Mo Arts Center, Beijing, January 22, 1994. © Xu Bing Studio.

While the video Xu shows in English-speaking venues is called A Case Study of Transference, his title for the original, 1994 live performance with the painted pigs was titled Wenhua dongwu (Cultural Animals). A third version of the work is titled, in English: Cultural Animal.15 This installation has two main components, arranged in a pigpen lined with torn books printed in several languages: a live male pig, again covered in nonsensical combinations of roman letters, and a life-sized mannequin of a human male, naked, on all fours, and painted with Xu’s invented Chinese ideograms. The artist doused the mannequin with sex hormones from a sow, and the boar obliged by humping the statue with abandon. The mechanics of this second setup are in some ways simplified (there are fewer moving parts), yet the piece introduces a disturbing dimension of bestiality—a human-animal interaction in which the “human,” rather than the animal, has been neutered—and, consequently, what Chen suggests is a queering of the boundaries between the animals we are and the animals we aren’t. Xu’s piece also directs the idea of “cultural animals” more forcefully at the audience: the spectacle makes animals of whoever stays to watch. Xu writes in his provisional wall text that “raw nature” confronts humans with feelings of “embarrassment and limitation,” but this is an understatement for such a raw encounter. It is more apparent in this iteration that it is the humans in the audience who are being fucked. Indeed, censoring the work precludes any relationship in which the audience might come to identify with other animals (whether dogs or pigs or human-Chinese or human-American) in ways more complex and fruitful than the determination of who is abusing whom.

Huang Yong Ping, Theater of the World (detail), 1993. Wood and metal structure with warming lamps, electric cable, insects (spiders, scorpions, crickets, cockroaches, black beetles, stick insects, centipedes), lizards, toads, and snakes, 59 x 67 x 104 in. Installation view, Akademie Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart, July 1, 1992-June 30, 1993. © Huang Yong Ping. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.

Animalworks constitute a signal movement in recent Chinese art. The Guggenheim’s attempt at historicizing Chinese art from 1989 to 2008 includes the category only in brief mentions of the censored works in the catalog—and in the wall labels that register the solipsistic fact that an American context met animalworks with censorship and violent threats. The encounter is crucial to these artworks, and no sanitized version is possible. Consider two pieces that fell outside the exhibition’s scope but that broaden the spectrum of experience explored by these artists and their peers. In Feng Weidong’s Muofan dongwu (Standard Animal, 2000), “The artist stands naked inside an iron cage.”16 Liu Jin’s Da jiang-gang (A Big Vat of Soy Sauce, 2000) finds the artist sitting naked in a giant pot of simmering soy sauce while holding a piglet. Such nonbinary experiences, neither congruent nor parallel, suggest links between human and animal that exceed the rubrics of “food,” “tool,” and “pet.”

Maintaining the three censored works as aporia in the exhibition leaves their horrors to the imagination. From this distance, it is understandable that activists would get carried away at the thought of works that they had never seen but that are powerful even when distilled as short descriptions. Yet so far as animalworks go, the three censored examples are relatively tame.17 In other cases over the last thirty years (in works not included here), Chinese artists have accidentally killed a pig, deliberately killed a cat, and melted a frozen greyhound corpse with a spotlight. (“The heat induces a steam to rise from the dead dog’s skull, while its thawed blood flows downward.”18) And yet the most photogenic piece censored from Theater of the World—and the one piece excluded from all three iterations, including the installation at the Guggenheim Bilbao—caused the biggest stir: a video work by Sun Yan and Peng Yu titled Dogs that Cannot Touch Each Other (2003), in which pairs of trained fighting dogs ran toward one another on clattering inclined treadmills. At the time the piece was filmed, one trainer was so pleased with the experience that he purchased several of the treadmills from the artists.19 Fifteen years later, three quarters of a million Westerners logged their protest with the Guggenheim—a cacophony that counter-protests and cries of censorship couldn’t overcome.

Even with the hindsight afforded the show’s third venue, SFMOMA decided to perpetuate the omissions of the Guggenheim, New York, as part of the historical record, displaying the absence of the works through stand-ins and blanks. The show’s curators and venues intended to outline for a Western audience the change in tone that occurred in Chinese art following a traumatic public massacre. Yet they not only bowed to misinformed public outrage but also incorporated the marks of their own self-censorship into the show’s history. Indeed, as Davis writes, beyond questionable treatment of animals and the caveats of free speech, the worst part of the whole affair is the missed opportunity for the institution to explain itself to the public.20 Rather than smoothing over these omissions, however, SFMOMA chose to leave what one reviewer calls “skylights,” referring to the practice in pre-Maoist China of leaving white space in the newspaper where content had been censored—as a warning and an invitation to self-censor.21 This sort of abstraction goes beyond the encoding that characterized art in post-Tiananmen China: the American response, instead, is a reactive abstraction to what it finds unpleasant.

This oversimplification cuts two ways: both overgeneralizing empathy in a way that erases nuance and denies conflict and overemphasizing difference in a way that sets up an almost condescending custodial relationship to the Other. Theater of the World shows, by example, how unwilling we are to admit to our own interspecies and intraspecies cruelty. This is an unhelpfully broad humanist statement. In contrast, consider another work in Theater of the World that—being purely descriptive—has slipped past the censors. In the painting Meat (1992), by Zeng Fanzhi, two men in a steel-grey room stand among hanging pig carcasses, shirtless in white (unsoiled) boxer shorts. Their ribs protrude, a little, and are ren- dered in the same kind of fleshy brush strokes as the chest cavities of the pork to either side. Art, it seems, is always about mortality, even when it is also about food.

Travis Diehl has lived in Los Angeles since 2009. His criticism appears widely. He is a recipient of the Creative Capital / Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant (2013) and a Rabkin Prize in Visual Arts Journalism (2018). Diehl is Online Editor at X-TRA and a member of X-TRA’s Editorial Board.