Tango with Cows: Book Art of the Russian Avant-Garde, 1910-1917, is the arresting title of an intimate, but illuminating, exhibition of Russian avant-garde books at the Getty Research Center. Taking its title from one of the most startling examples of the Modernist book, i.e. Vasilii Kamenskii’s Tango s korovami: Zheleznobetonnye poemy (Tango with Cows: Ferro-concrete Poems, 1914) with its wallpaper covers and fractured form,1 the Getty exhibition presents the Russian avant-garde as a generator not of innovative paintings, constructions, architecture and stage designs, for which it is widely recognized, but of highly experimental books, journals, leaflets, manifestoes and other printed ephemera. Tango with Cows focuses on the climactic moment of the Russian avant-garde—the years just before the October Revolution, when painters, poets and musicians were creating a veritable renaissance of the Russian arts and letters.

Vasilii Kamenskii, Tango with Cows: Ferro-concrete Poems (Tango s korovami: Zhelezobetonnye poemy), Moscow, 1914. Cover: Vasilii Kamenskii. Letterpress and wallpaper. Research Library, the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California.

Curated by Nancy Perloff and Allison Pultz, who have turned the modest space of the exhibition room of the Research Institute into an avant-garde laboratory, Tango with Cows presents a small sampling of the over one thousand Russian avant-garde books in the Getty collections. Unlike other exhibitions of the Russian avant-garde book in the USA and Europe, Tango with Cows concentrates not only on the often bizarre visual appearance of these books, but also on the elicitation of their poetical sounds, offering liberal transliterations, translations and recitations of often highly complex verbal instrumentations to which the visitor can listen. With lucid didactic information, an extensive chronology and terse comments on individual books, authors and illustrators and their affiliations, Tango with Cows enlivens what is often presented as an exclusively academic and recondite subject. Of particular interest are the perfect facsimiles of some of the more celebrated books, reproducing not only the words and images of the original, but also its dedications, tears, cracks and even mildew stains. These facsimiles, which at first glance pass easily for originals, provide the visitor with the opportunity to see, touch, handle, hold and even smell the materiality of these miniature artifacts, a sensual feast which, of course, is lost in digital duplication.

On many occasions, the stylistic concepts which informed the unruly surface of these books—Neo-Primitivism, Cubo- Futurism, Rayism and Suprematism—and the artists and writers who elaborated them such as David Burliuk, Pavel Filonov, Natalia Goncharova, Velimir Khlebnikov, Aleksei Kruchenykh, Mikhail Larionov, Kazimir Malevich, and Olga Rozanova anticipated later, more celebrated movements in the West such as Dada, Actionism, and Conceptual Art. Thanks to an introductory section on the Symbolist press, Tango with Cows demonstrates just how revolutionary the avant-garde was in its rejection of the decorative elegance of the fin de siècle, encapsulated in the sumptuous journals Mir iskusstva (World of Art) and Zolotoe runo (Golden Fleece) (both on exhibit). Moreover, the exhibition reminds us that there was not one avant-garde, but many, and that, if Moscow and St. Petersburg were the axes of the movement, regional cities were also active. Tiflis, for example, offers a Georgian interpretation of Cubo-Futurism in Kruchenykhs’s and Kirill Zdanevich’s Uchites, khudogi! (Learn Artists!) of 1917.

Aleksei Kruchenykh, A Game in Hell: A Poem (Igra v adu: Poema), Moscow, 1912. Cover: Natalia Goncharova. Lithography. Research Library, the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California.

Practically all the artists of the Russian avant-garde gave their attention to the design, illustration, and manufacture of the book. The Burliuks, Goncharova, Larionov, Malevich, etc. dismissed the preceding canons of good taste and stressed the transient, accidental, and manual aspects of the book, using typographical error, inaccurate pagination, and deliberate ambiguity of letter and picture in order to overcome the conventional barrier between word and image on the page, something that we see again and again in Kruchenykh’s booklets of 1912-14 such as Igra v adu: Peoma (A Game in Hell: A Poem, 1912).

Many of the artists were also poets, and some of their literary colleagues such as Khlebnikov, Kruchenych, and Maiakovsky could draw and paint. The books which they created are exciting and often exasperating, not only because they use word and image to parody and scandalize, but also because they constitute a repertoire of the stylistic and formal ingredients of the avant-garde endeavor—displacement, asymmetry, spontaneity, automatism, parody, shock, incompleteness and so on. Consequently, common aesthetic formulae might inform a painting and a book design simultaneously; sometimes the illustrations themselves anticipate or repeat the subjects of major studio paintings, Filonov’s Propeven o prosroli mirovoi (A Chant of Universal Flowering) (Petrograd, 1915) being a case in point. But occasionally, these renderings may lack any apparent bearing on the poetical message, acting as visual enhancements of, rather than illustrations to, the text—such as Malevich’s “irrelevant” lithograph Arithmetic inserted into Kruchenykh’s poem Vozropshchem (Let’s Grumble) of 1913. Such lithographic addenda may often seem to be meaningless, but, then, zaum (lit. “transrationality”) was an organic component of the avant-garde project and conscious non-sequitur and catachresis were among the weapons with which the avant-garde attacked Victorian common sense and order.

Tango with Cows gives particular attention to this topsy-turvy world not only by displaying pages of zaum poetry, but also by providing the visitor with recorded declamations of this “nonsense” as well as valiant, but inevitably inadequate, translations into “English.” Indeed, as the Getty exhibition confirms, the early book productions of the Russian avant-garde such as the second edition of Igra v adu in 1914, with illustrations by Malevich and Rozanova, deviated radically from the traditional principles of composition, pagination, and format. On the other hand, it should be emphasized that this interdependence of image and text was not new in the history of book design, for there were similar concordances in the Persian miniature, the Mediaeval Book of Hours, and the 18th and 19th century Russian lubok (handcolored broadside), and how fortunate that Tango with Cows was paralleled by the superb exhibition of the illuminated manuscript The Belles Heures of the Duke of Berry in the Getty Museum at the same time.

Vasilii Kamenskii, Transitional Boog (Zaumnaia gniga), Moscow, 1916. Cover: Olga Rozanova. Collage and letterpress. Research Library, the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California.

It was precisely because the book held such a central position in traditional Russian culture that the artists and writers of the avant-garde gave marked attention to it, attacking and displacing its strong conventions of propriety and inventing new concepts of reading, writing, and printing. Indeed, one of the strangest conditions governing the Western appreciation of the Russian avant-garde books—and one certainly true of the Getty exhibition—is that they tend not to be “read.” They are often acquired by collectors who cannot read Cyrillic and who value the books as material objects to be seen and touched and not as sources of narrative, intimate colloquy or enunciation; critics marvel at the textures, typefaces, illustrations, and grades of paper, but not, unless they know Russian, at the “meaning” of the text. On one level, this is exactly what the avant-garde desired, i.e. for the reader to stop reading and start looking, a dramatic shift of priorities in the reception of the book as a literary entity. Furthermore, the books themselves (sometimes printed, sometimes handmade, sometimes issued by a publishing-house, sometimes distributed by hand) are now very rare owing to their fragility and limited editions (not uncommonly in a press run of three hundred copies) and there are often discrepancies in pagination and illustration between one copy and the next.

For all their ebullience, artists such as Burliuk and Goncharova were no less esoteric and élitist than their Symbolist predecessors; they may have censured the fin de siècle, but paradoxically they assured continuity by repeating many esthetic and thematic parallels. Like the Symbolists, the avant-garde artists also issued books in limited editions, wrote cryptic and oblique poetry, appealed to the linguistic registers of children and animals and dreamed of the marriage of word and image. On the other hand, the Cubo-Futurists did not sympathize with the theocratic interests of the preceding generation, they had little patience with “beauty” and “measure,” and they tended to regard the reader as a guinea pig rather than as a respectable ally. In the context of actual book production, too, the avant-garde followed a very different approach, something immediately manifest from the choice of shocking titles for their societies and books such as “Jack of Diamonds,” Moloko kobylits (Milk of Mares by Khlebnikov et al. with illustrations by the Burliuks and Alexandra Exter, 1914) and, of course, Tango s korovami.

As is clear from Tango with Cows, a strong aspiration on the part of the avant-garde book designers was not only to replace “high” with “low,” but also to reconsider the book as a physical, tactile thing. Items such as Tango s korovami and Zaumnaia gniga (Transrational Boog, 1916) by Kruchenykh and Roman Yakobson are, indeed, substances not only because they are spatial entities, but also because the ways in which they are “built” (with varying kinds of papers, collages, bindings, etc.) reinforces the sense of material facture. By now certain key monuments to this esthetic are widely known and, quite rightly, they take pride of place in the Getty show, including Goncharova’s and Larionov’s collaborations with Kruchenykh, e.g. Igra v adu and Rozanova’s and Kruchenykh’s bellicose collages called Vselenskaia voina (Universal War, 1916).

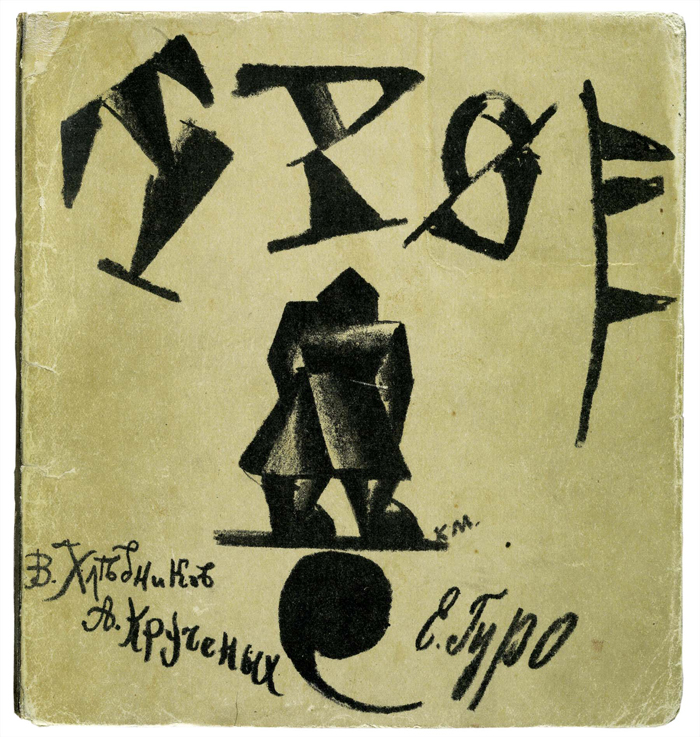

Velimir Khlebnikov, Threesome (Troe), St. Petersburg, 1913. Cover: Kazimir Malevich. Lithography. Research Library, the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California.

The designers of the avant-garde book rejected the esthetic position of the late Victorian tome with its retrospective sentimentalism and Art Nouveau covers, its serpentine illustrations, and parchment paper, and returned the book, the poster, and the postcard to the status of the lubok. Often the poets and painters relied on handwritten script and rude illustrations, incorporating mistakes in spelling and grammar. They cultivated the art of the “absurd” in transrational combinations of the casual and the spontaneous, including children’s poems and drawings, or played with derivations of naughty words. The conscious mystification of authorship, as in the multifarious poetical experiments of Larionov’s and Goncharova’s collection called Oslinyi khvost i mishen (Donkey’s Tail and Target, 1913), is very different from the disciplined elegance of the Symbolist and World of Art artists such as Léon Bakst, Alexandre Benois and Konstantin Somov.

Instead of being an object of discernment and esteem, the avant-garde book now became a joke (cf. Porosiata [Piglets] by Kruchenykh and Zina V., 1913); instead of being a source of solace, it now upset the reader’s peace of mind, demanding an active, creative involvement; instead of being a symbol of truth and permanence, it was now a throwaway item; and instead of being a production of reason, its language, as Kruchenykh asserted in his Deklaratsiia slova kak takovogo (Declaration of the Word as Such) of 1913, “has no definite meaning.” Just as the old lubki parodied important personages and social foibles, rendering them accessible to an often illiterate public, so the Cubo-Futurist booklets used analogous methods, relying on handwritten script and rude illustrations, spelling and grammatical mistakes, and cheap, “unartistic” paper. (The first issue of Sadok sudei [A Trap for Judges] by Vasilii Kamenskii et al. [1910] was printed on wallpaper just as Tango s korovami was.)

In their quest for new concepts and systems, painters such as Goncharova, Larionov, and Malevich gave pride of place to the indigenous arts and crafts such as the toy, the icon, the lubok, the distaff, embroidery, and urban folklore, borrowing motifs and devices which they transferred to their own artistic repertoire. Neo-Primitivism was the direct consequence of this: for example, Malevich rendered ordinary scenes of the peasant life that he knew so well as book illustrations (cf. his sturdy peasant woman on the cover of Troe [Threesome] by Khlebnikov, Kruchenykh, and Elena Guro [1913]); Goncharova expressed her interest in religious folklore in her illustrations to Misticheskie obrazy voiny (Mystical Images of the War, 1914); while Larionov, on the other hand, looked to the city with its graffiti, whorehouses, and taverns for inspiration (cf. his illustrations for Kruchenykh’s Poluzivoi [Half-Alive] of 1913).

Goncharova and Larionov prepared the way for other audacious designers, especially Malevich, who, in his paintings and illustrations, owed a great deal to the Neo-Primitivist esthetic. Malevich even paraphrased some of Goncharova’s themes: his lithograph called Simultaneous Death of a Man in an Airplane and on the Railroad (1913), which appeared in Vzorval (Explodity), parallels Goncharova’s canvas entitled Airplane above a Train of the same year (State Art Museum, Kazan), while his untitled lithograph of a carriage in motion in Troe brings to mind Goncharova’s Cyclist of 1912-13 (State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg).

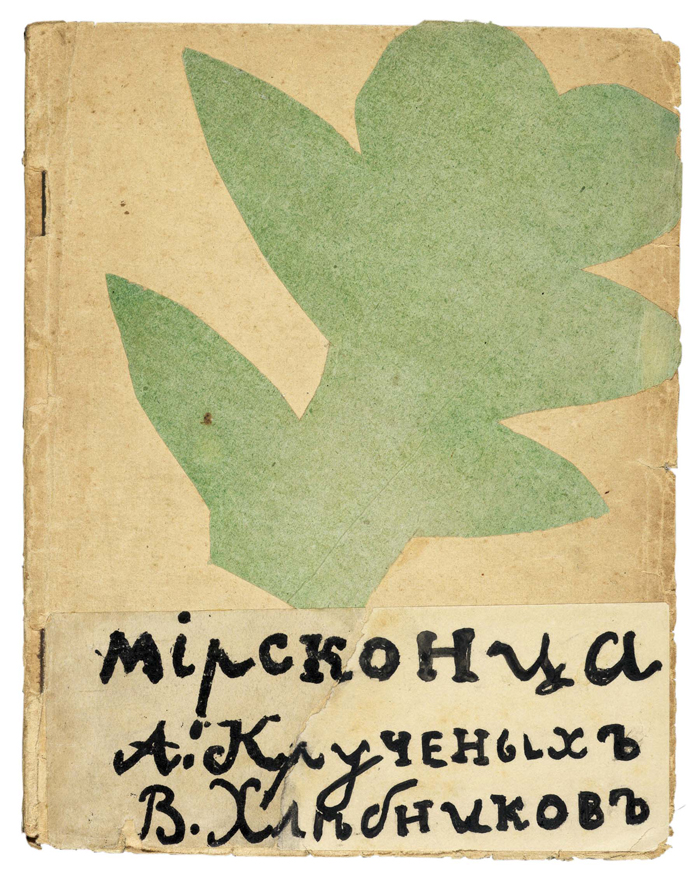

Aleksei Kruchenykh, Worldbackwards (Mirskontsa), Moscow, 1912. Cover: Natalia Goncharova. Collage and lithography. Research Library, the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California.

Perhaps Filonov also studied the book experiments of Goncharova and Larionov before arriving at his own idiosyncratic conclusions, for his interest in motifs from Russian mythology and his emphasis on the pictographic quality of the written word find precedents in Goncharova’s conception of Igra vadu and Larionov’s “Letters at liberty” in Mirskontsa (Worldbackwards). An especially striking conjunction of aural and visual devices is to be found in Filonov’s designs for Khlebnikov’s poem “Dereviannye idoly” (“Wooden Idols”) in Izbornik stikhov (Miscellany of Verse, 1914), where he matched the poet’s often abstruse and archaic vocabulary with a more accessible visual entertainment in the form of ideograms. For example, he drew the first letter of the word rusalka as a bare-breasted mermaid and suspended the middle letter of the verb “uletat” (“to fly away”) above the rest of the word, playing a sophisticated calligraphic game with the reader-cum-viewer.

Like Filonov, Rozanova, too, owed much to the Neo-Primitivist discoveries and her designs for the second edition of Igra v adu are clearly inspired by Goncharova’s drawings for the first. At the same time, as we see at Tango with Cows, Rozanova experienced the influence of Italian Futurism, exploring the themes of speed and modern technology in both her paintings and her prints. Her cover for Vzorval, for example, indicates that it was a short step to her elaboration of an abstract art dependent upon the integration of its internal components, and her illustrations (with Kruchenykh) for Vselenskaia voina functioned with what she called “purely artistic achievements”: using a sequence of twelve non-figurative colored paper collages, Rozanova and Kruchenykh “illustrated” a book that had no text. The fact that the artists and writers of the Russian avant-garde concentrated on the book and that they exploited it deliberately as a primary method of communication demonstrates that, for all their scandalous behavior, they still retained a traditional respect and passion for the book as a unique and special artifact—and they were among the last to do so. In this respect, Tango with Cows pays homage not only to a radical reinvention of the book, but also to the very procedure of reading and writing the book which, with the contemporary imposition of electronic media, are under ever stronger attack.

John E. Bowlt is a Professor of Russian art at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, where he is also Director of the Institute of Modern Russian Culture. Among his recent publications is the book Moscow, St. Petersburg, 1910-1930. The Silver Age.

Unless stated otherwise, all titles mentioned are on display at the Getty exhibition.