For all of Tim Hawkinson’s entertaining use of sound and movement in his work, his sculpture’s stunning inventiveness and the way it responds to the history of media and technology, he is ultimately interested in some very old questions. Hawkinson connects the more recent influences of conceptualism, kinetic art, sound and installation work to a tradition of philosophical speculation and religious thought deeply embedded in American culture and most famously articulated in the 19th-century literature of Emerson, Whitman, and especially Herman Melville. But his work is far from “literary” in its experience and instead drops you in the middle of an age-old puzzle about the nature of our world and our place in it—forcing you to grapple with the meaning of all the strange sounds, intricate constructions and whirring machines that surround you. The recent retrospective of his work at LACMA, designed and installed by Hawkinson himself, presents a self-portrait of the artist as engaged in an obsessive, philosophical quest, in which anything, from manila envelopes to model ships, can take on special significance. To get at some of the fundamental issues in Hawkinson’s varied sculptural practice, I will focus here on the parallels between a few pieces which use the nautical as a metaphor for a mode of philosophical inquiry that is present in much of his other work.

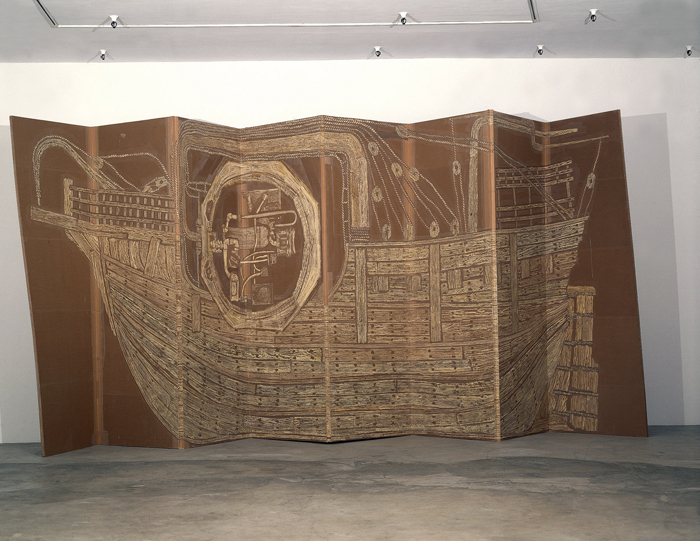

Although the rambunctious figures of Pentecost (1999) greet you upon entering the exhibit by drumming on the sprawling cardboard tree in which they sit, a related piece in the adjoining room signals Hawkinson’s specific interest in philosophy and American literature. Crow’s Nest (1998), an image of a wooden sailing ship mounted on a 12-by-32-foot folded polystyrene panel has been overlooked in recent discussions the show. It stretches along the wall between the two passageways leading from the room containing Pentecost and this proximity underscores the formal relationship between the two pieces. Hawkinson created the wood pattern covering the sonotubes which make up the tree in Pentecost by replicating the pastel rubbings on craft paper of a wooden deck used in the earlier Crow’s Nest piece. While Pentecost refers to the ecstatic moment in which the Twelve Apostles received the Holy Spirit and began speaking in tongues, Crow’s Nest is a cryptic juxtaposition of an image of the inner workings of a hot tub and a wooden patio deck depicting a three-masted sailing ship seen from the side. The title refers to the nautical term for a small, one-person vantage point situated near the top of one of the masts on the kind of 19th-century whaling vessel pictured in this work. In chapter 35 of Melville’s Moby-Dick, “The Mast-Head,” Ishmael describes the experience of standing high above the ship’s deck, meditating upon the empty ocean vistas surrounding him while supposedly keeping watch for whales:

With the problem of the universe revolving in me, how could I—being left completely to myself at such a thought-engendering altitude,—how could I but lightly hold my obligations to observe all whale-ships’ standing orders, ‘Keep your weather eye open, and sing out every time.’…Lulled into such an opium-like listlessness of vacant, unconscious reverie is this absent-minded youth by the blending cadence of waves with thoughts, that at last he loses his identity; takes the mystic ocean at his feet for the visible image of that deep, blue, bottomless soul, pervading mankind and nature; …In this enchanted mood, thy spirit ebbs away to whence it came; becomes diffused through time and space…forming at last a part of every shore the round globe over.1

Ishmael’s discussion here is in keeping with the novel’s general structure in which every aspect of the ship and the doomed voyage of the Pequod is symbolic of the elemental conflict between the feverish urge to know the meaning of the world and the limits of human knowledge in the face of God and the sublime. Hawkinson’s substitution of a hot tub for the crow’s nest, then, might be read in the context of the ponderous, speculative mood of the above passage. Perhaps this a reference to the stereotype of the Southern California lifestyle, in which an Ishmael in his hot tub at the mast-head can lie back and meditate on the meaning of it all, rather than setting his sights on his career goals or scanning the horizon for the possibilities of a promotion. But Hawkinson’s installation of Crow’s Nest at LACMA suggests that there is something deeper at work here.

Hidden behind Crow’s Nest, Hawkinson has placed Penitent (1994), a small human skeleton made out of rawhide dog chews. The figure’s ribcage contains a motorized device which blows a slide-whistle, giving the impression it is calling for a dog. Kneeling on the floor in a position of supplication, the skeleton seems to be beckoning for it’s own demise in the form of a dog which will tear it apart. While a separate work, Hawkinson’s installation of Penitent builds upon the themes of Crow’s Nest, especially considering the memento mori message with which Melville ends “The Mast-Head” chapter. Ishmael’s solitary reverie at the mast-head is interrupted by the thought of the quick and easy death that could be the result of a simple mistake: “But while this sleep, this dream is on ye, move your foot or hand an inch, slip your hold at all; and your identity comes back in horror… with one half-throttled shriek you drop through that transparent air into the summer sea, no more to rise for ever.”2 Death, then, lurks behind Hawkinson’s image of a hot tub on a yacht.

Hawkinson has made a number of other nautically oriented pieces. He seems drawn to the 19th-century era of ocean exploration and commercial exploitation, in fact, as his other work in this vein employs imagery of the three-masted sailing ship depicted in Crow’s Nest. Siren Trouble (1994) is a plastic model of the USS Constitution caught in a web of string and a wooden frame. In one of his earliest works, Untitled (Sinking Ship) (1987), Hawkinson painted an image of a sinking ship in a simple, vernacular style on the fabric liner of wig. He shaped the hair into a mandala-like arrangement of curls and then he encased the entire wig, picture-side up, in thick layers of varnish. In other work, Hawkinson focused on the masts of these kinds of boats in particular, creating elaborate constructions out of the vertical and horizontal elements of the masts and rigging, as in Das Tannenboot (1994) and Aerial Mobile (1998)—both tangles of wood and string, but clearly recognizable as ship-in-a-bottle projects gone awry. H.M.S.O. (1995) is another one of these works, which unlike the others, was included in the LACMA exhibit. The title refers to the designation of British navy ships (“Her Majesty’s Ship…”) and the “O” reflects the circular structure of the piece—a conglomeration of ships’ hulls formed into a giant wheel of laminated wood. Turning in on itself in a gesture of futility or solipsism, H.M.S.O. is a forest of masts, sails and rigging pointing into its center. Considering the importance of Crow’s Nest as a marker of the underlying themes of his work, it is interesting that the exhibition catalog description of H.M.S.O., which the artist himself wrote, identifies this aspect of the ship’s anatomy specifically: “A circular hull… outfitted with masts and jobs, yardarms, sails, crow’s nests, etc.”3 Resonating with the dangerously self-reflective mood of the Melville’s “The Mast-Head” chapter, the crow’s nests in H.M.S.O. represent a kind of persistently inward vision.

Prior to this installation of his work in a major travelling museum show, Hawkinson’s most ambitious piece in terms of scale and complexity was Überorgan, commissioned by Mass MOCA in 2000 for its huge, 18,000-square-foot, gallery 5 space and not included in the show at LACMA. A tremendous construction of plastic balloons, ducts and pipes connected to horns playing prerecorded tunes, Hawkinson describes the piece as a “walk in self-playing organ.”4 Überorgan is a visceral representation of the aesthetic notion of the sublime—the awe-inspiring experience of phenomena beyond human comprehension. As the bellowing series of translucent, room-sized balloons take on the color of the white walls surrounding them, Überorgan strongly evokes Melville’s famous white whale. In discussing the piece in Artforum, in fact, Hawkinson suggested as much: “I learned that Herman Melville wrote Moby-Dick while he was living in Pittsfield, which is just down the road from Mass MOCA. My piece relates to the book and more generally to the nautical, with all the netting and lashing and rigging and the foghorn-like sounds and the massive rib cage and organs.”5 Überorgan ultimately emphasizes the importance of scale in the experience of sculpture, an issue Hawkinson takes up in different ways in other work concerned with mapping, documenting and otherwise gauging our bodily and mental relationship to the nature of space and time.

The LACMA show provides many opportunities to experience these kinds of works, from the Secret Sync (1996) series of clocks made from objects such as a manila envelope and a tube of toothpaste to the endlessly intertwining doodles of the enormous Wall Chart of World History from Earliest Times to the Present (1997). But the human body, both the viewer’s and Hawkinson’s, is often at the center of this kind of work. Several of Hawkinson’s pieces in which he attempts to document and systematically observe the physical limits of his perception are also on view, such as Blindspot (1991) and Humongulous (1995). In these works, Hawkinson methodically charts all the areas of his body that he can and cannot see, which displays an obsession with pinpointing the boundary between himself and the world. Such work seems to ask how much of what we know and observe is literally a product of our own perspective.

Much of Hawkinson’s art engages the viewer with its provocative use of technology, such as the air pump used to create the “breathing” effect of one of LACMA’s gallery walls in Reservoir (1993). But less immediately arresting pieces such as Crow’s Nest offer a context for understanding the philosophical issues Hawkinson pursues throughout his multi-faceted practice. Hawkinson’s retrospective was one of the most popular in Los Angeles this season. But beyond the initial fascination with technique and materials, his work provides a compelling opportunity for the public contemplation of the kinds of existential questions usually confined to our more solitary moments.

Ken Allan is a Visiting Lecturer in modern and contemporary art in the Department of Art & Art History at Scripps College and is currently working on a book about the relationship of artistic practice and social space in 1960s Los Angeles.