Janiva Ellis makes paintings fraught with tension and exaggerated expression, filled with cartoonish images and the playful, even psychedelic narratives they carry. Each scene tells the tales of these sensations as wrought in daily life. Ellis’s vivid and growing visual vocabulary is employed, as she says below, “like a gloved hand, muting its individuality yet exaggerating its gesture.”

Gloved hands often appear in Ellis’s works. In 2017, she presented Lick Shot at 47 Canal, her first solo show in New York. This exhibition included a series of works variously populated with layered figures and gestures, sometimes against a glimpse of blue sky. More recently, Ellis made a set of paintings for Songs for Sabotage, the 2018 New Museum Triennial in New York. These scenes have grown larger, their skies now filled with both puffy clouds and ominous smoke.

I wanted to find out more about Ellis’s recurring cast of forms and the circumstances in which they are found, made, and are reflective of. Ellis divides her time between Los Angeles and New York, and we carried out our interview in writing during May and June of 2018. Our conversation has been edited for print.

Janiva Ellis, Scambient Pet, 2017. Oil on canvas, 70 × 40 in. Courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

LAURA BROWN: When did you begin making paintings?

JANIVA ELLIS: When I was ten I had a mentor, named Tammy Day. She was twenty and one of the first black women I had ever really known. I would go to her house after school. We would listen to music and watch movies, and I would try to redraw things from her sketchbook. Her presence was so positively informing and affirming for me. I had always liked to draw, but this relationship changed its significance.

I studied painting at California College of the Arts in San Francisco. After graduating, I felt burnt and unmotivated, and I slowly stopped painting. It took about four years, until winter 2016, for me to begin navigating a solid painting practice again. I returned to painting in a really casual way. Once I stopped trying to engage the performance of what I thought a studio practice should be, I was able to access what it could be really easily. A lot of bottled up imagery leapt out. Rendering flat images was a really lighthearted entry point and something I had never done before. It was so much faster, and I could say so much more.

BROWN: In an unpublished interview, you talk about your work as a means for “translating experiences that inform my adulthood.”

ELLIS: I moved to Hawaii when I was seven, moving back and forth between Kauai and Oahu. I was raised solely by my mother, who is white. Hawaii’s population, although not predominantly white, has a very small black population. This racial dynamic fostered an awareness of difference that resulted in a desire to blend in, despite being an otherwise outgoing child.

Being black in Hawaii was an experience I didn’t fully acknowledge as isolating until I moved back there as an adult. After living in San Francisco and New York, I realized how alone parts of my adolescence had felt. The paintings I made this past year helped me to decipher how that remoteness manifested itself as a specific type of hesitance and self-doubt in my adulthood.

Hawaii is stunning, so serene and idyllic. My mother was nurturing and supportive. In many ways, my childhood felt charmed. It was hard to understand why it was the site of such uncertainty until I lived in cities with black communities. A lot of the content that surfaces in my work can be applied to a variety of black American experiences, but it generally stems from my own. The symbolism in my work is not quarantined to blackness, it’s inherently black because I am.

BROWN: Does a particular method drive your process and compositions?

ELLIS: There is no method in my practice that functions in a singular and recurring way. It’s often a question of how big I want to see a certain image or conversation. There’s usually a collaging of imagery that runs through my work, but not all my compositions are bound by this. Originally this stemmed from an impatient urgency to get everything down, but has evolved into more of a language. I learned from this chaotic method that the variety of mark making that can be achieved with paint can be infinitely communicative. The way a figure is painted in relationship to other figures or its environment can be as instructive to the narrative as the figure itself.

BROWN: In the past you’ve used found canvases and painted over existing paintings, interacting with these paintings like ghosts.

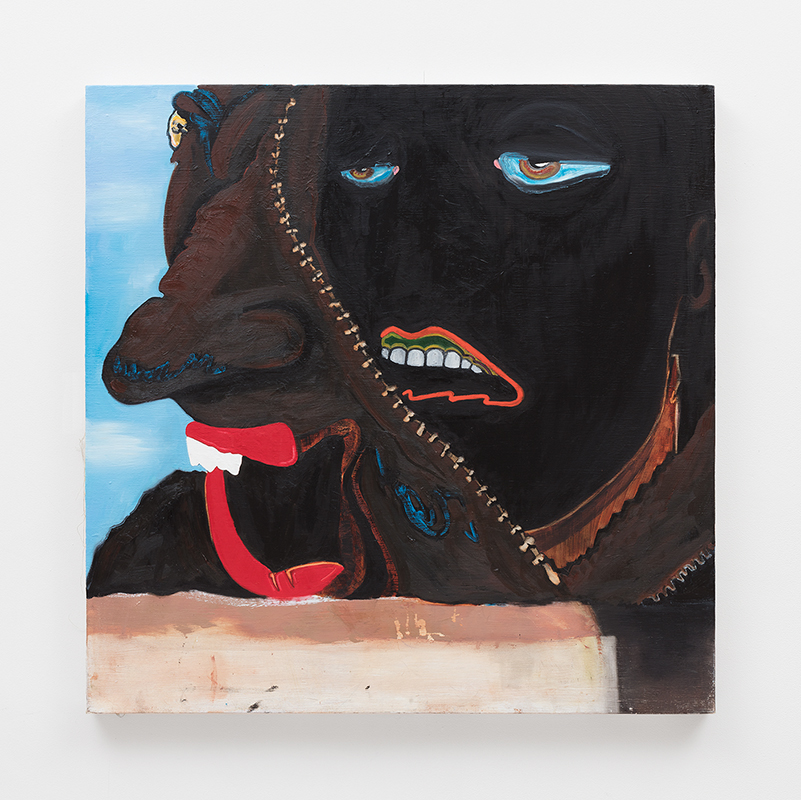

Janiva Ellis, Open Pour Reality, 2017. Oil on canvas, 35 1⁄2 × 35 1⁄2 in. Courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

ELLIS: I love painting on found work because it gives me parameters to work within. The pre-existing composition loosens up how I start a painting and sets a tone of playfulness. I often choose to keep passages from the underlying piece that I see as triumphs or as complementary to the new marks I’ve made.

For Open Pour Reality (2017), I painted over a painting I made in college. It felt so good to cover it up. I saved my favorite part of the piece so as not to forget its origin. Revealing a layer of the painting’s previous life folds into the idea of masking, which is also literally portrayed in the painting.

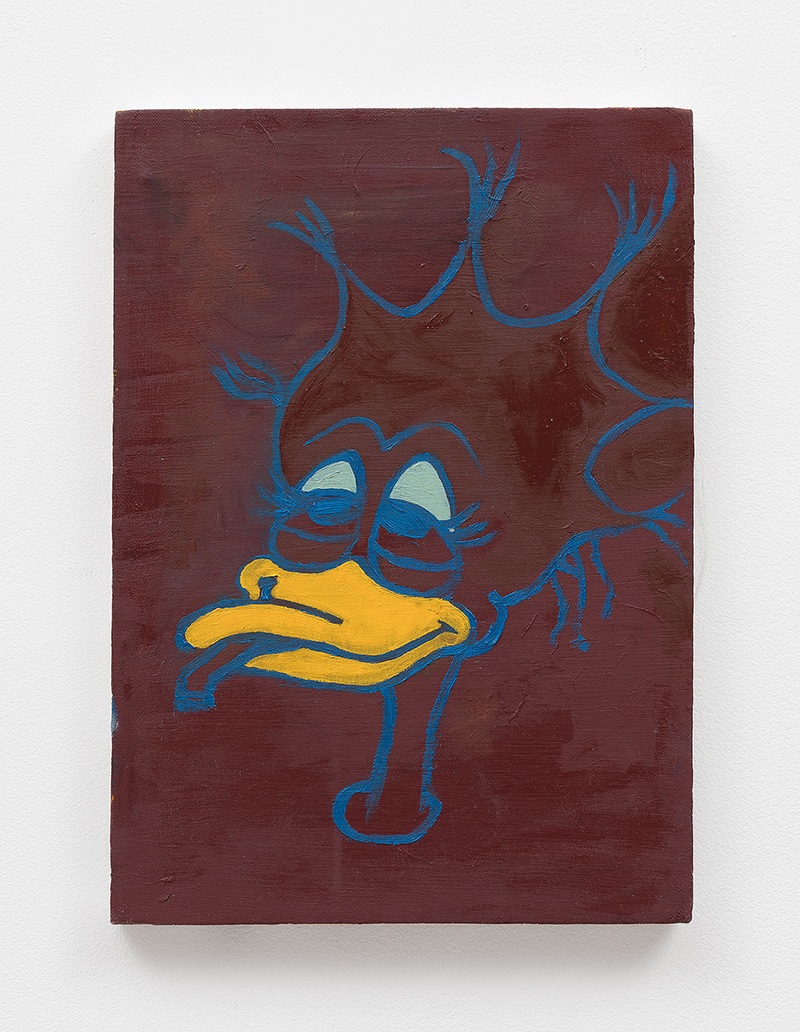

I generally have a palette painting that I work on alongside a more intentional piece. The palette painting is just a place to put excess paint and has a more automatic movement to completion. Duck Duck Deuce (2017) was an automatic palette painting I made on a found canvas. I only realized it was finished when a friend admired it.

BROWN: Aside from your palette paintings, do you map out your works in advance?

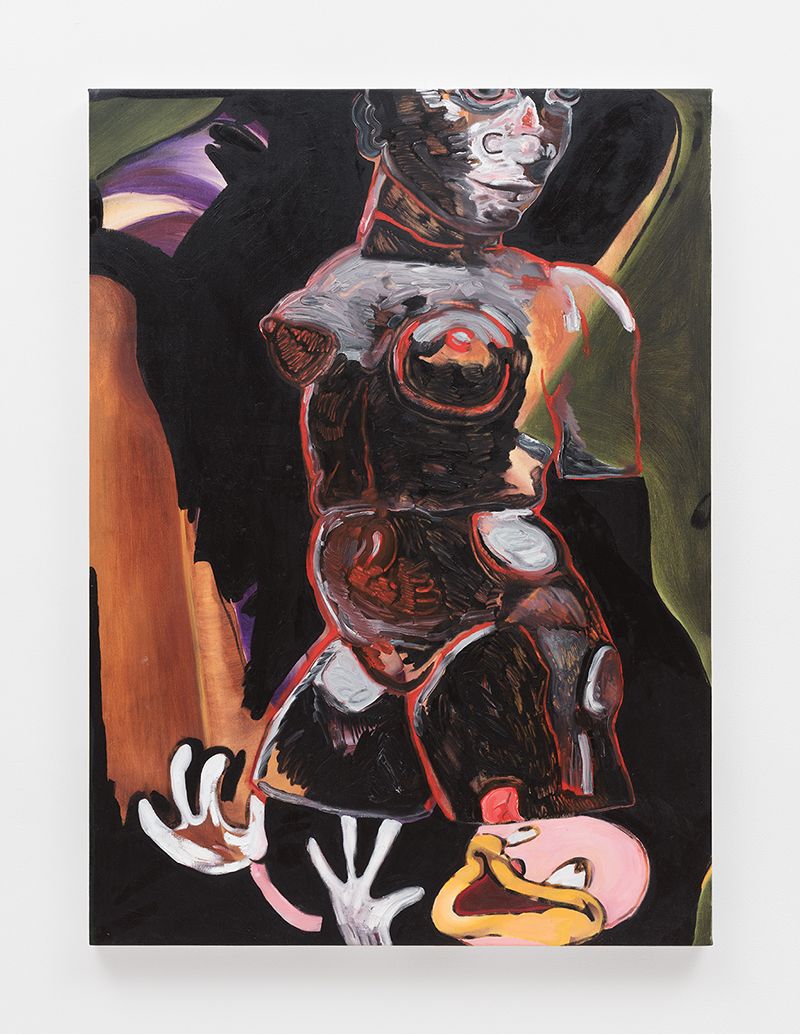

ELLIS: The approach varies from composition to composition. Many of the works in my first solo show, Lick Shot (2017), were painted on top of recycled pieces, either found or my own. I painted directly on top of them, maintaining both formal and structural parts that I liked. Elements of the original compositions peeked out from underneath. In Memorializing My Industry In Sculpture (2017), I left previous passages of color but carved out a new background with black paint. In retrospect, this method of painting on paintings was a low stakes entry back into making work. I didn’t overthink the outcome because the painting was already there. At the time, I had no other canvases to paint on. I haven’t painted on top of paintings since that show, but I definitely welcome it.

Janiva Ellis, Memorializing My Industry In Sculpture , 2017. Oil on canvas, 47 1⁄2 × 34 1⁄2 in. Courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

When a work relies on accuracy for its communicative success, I use a projector. In Curb Check Regular, Black Chick (2018), I projected a still from the anime Perfect Blue (1997, directed by Satoshi Kon) as an armature for the composition. I really appreciated the sense of isolation in a crowd that the film still was able to evoke and wanted to apply it to my own narrative. I collaged on other imagery, both sourced and invented, to complete the story.

I’ve played with incorporating paintings by “masters,” inserting their backgrounds into mine. Doubt Guardian 2 (2017) has an early Neo Rauch composition nestled in the background. These choices, while being very conscious, are usually whimsical or comical and are not necessarily integral to deciphering my work.

There’s no real formula for the conclusion of a work. A lot of the techniques are born in pursuit of completion.

BROWN: Do you consider your works to be self-portraits?

ELLIS: Bloodlust Halo (2017) is a self-portrait. It’s one of the earlier things I did last year. I looked at a photograph of myself and freehanded it on top of an old painting. I was dissatisfied with the way that it looked. I made so many attempts, building layers and layers of paint. I got frustrated and started scraping them off to start fresh. In that scraping, a texture occurred that I then began building on. The way this painting came to be—the scraping—felt like the true portrait. That is the only self-portrait I’ve done recently, but I definitely exist in a lot of my work.

Janiva Ellis, Doubt Guardian 2, 2017. Oil on canvas, 60 × 48 in. Courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

BROWN: Your paintings include a wide recurring cast of characters, like the cartoon duck.

ELLIS: The duck initially emerged through a desire to simplify my approach to painting. I wanted to get my ideas down more quickly and efficiently, but I hadn’t ever tried flattening the images in my paintings. The first one I did was of this picture of a sleepy Daisy Duck (or maybe one of her relatives). She looked playfully drained in a way that I identified with, so I made her black using brown paint.

I wanted to see how a duck could relate to a human figure, how flatness could engage depth. In Hunt Prey Eat (2017), I painted a picture I had seen on Instagram of my friend Jasmine in a swimming pool. She looked so carefree. When I added Daffy Duck, a narrative began to form that automatically went to hunting. I thought of violence committed against the innocent and unassuming. Although it was not my intention to explicitly reference or co-opt a specific instance of injustice or brutality in this work, I thought of 15-year-old Dajerria Becton, who was attacked by a cop at a pool party in McKinney, Texas. Hunt Prey Eat taught me about the power of implication through simple compositional interventions.

The ducks in my paintings became an entry point for talking about racialized experiences of blackness, both personally and broadly. This approach loosened up the preciousness I previously had around painting and very quickly and naturally created a dialogue surrounding race.

Ultimately, I want my paintings to be enjoyable for people who don’t have a formal understanding of histories of mark making. I don’t want to lock anyone out. I want to slowly un-complicate an often abstruse dialogue.

BROWN: Your stylistic mode of cartooning seems to differ depending on the figure.

ELLIS: The way I render a figure in an image is usually in relationship to the other figures that accompany it and the dynamic that two figures might share. The importance of the characters’ recognizability is relative to the narrative being depicted.

In Memorializing My Industry In Sculpture (2017), the relationship between the black sculptural figure and the pink toon illustrates a dynamic that is both figurative and literal. The black figure is gestural yet intentional. The toon is crude and hapless yet so proud and exalting of the sculpture, as if he had made it himself. The dynamic in this instance loosely describes how black ingenuity is commonly engaged by white or pink audiences—as if its members are proud of themselves for elevating what they’ve “found.” Enthusiasm as bondage. In this instance, the cartoon speaks to a general behavior versus a specific cultural icon that is being recontextualized.

In Something Anxiety (2017), it was important that Sebastian (from Walt Disney’s 1989 The Little Mermaid) be plausibly recognizable. I wanted to reference my early memories of media from childhood. Regardless of how many important black films or characters there were, a Tom Cruise-esque figure was being plastered on top of them. Sebastian makes an appearance in this work as one of the earliest black cartoons I knew of. I wanted to playfully honor him even though he doesn’t manage to escape his doting proximity to whiteness in my piece. By painting Sebastian brown, he is both distanced from and reattached to his origin.

Janiva Ellis, Something Anxiety, 2017. Oil on panel, 60 × 60 in. Courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

BROWN: Like Sebastian, the figures in your works are often referential, borrowed from elsewhere. Once in the works, how important is this tether to you?

ELLIS: The importance varies. Oftentimes I repurpose or borrow images to change their context or transform their original purpose to suit my needs.

There is a history of image making in both pop culture and the canon of art that has been given an inflated sense of merit, most of which ignores or degrades the existence and irreplaceable contributions of black people. Referencing a scene from Ren and Stimpy (by illustrator John Kricfalusi) or borrowing a background from painter Andrew Wyeth transforms my relationship to familiar works and mirrors customs of capturing without acknowledgement that are so pervasive within the history of widely lauded image making. I’m not implying that those I borrow from do this directly, but those I’ve borrowed from thus far are generally people who’ve directly benefited from histories of appropriation. Taking without thinking is a long-lived tradition that I enjoy playing with.

Parallel to this is the touristic inclination to reference and depict that which is inspiring as personal experience, rendering a voyeuristic perspective as one’s own. I’m interested in the various manifestations that this can take. Using a composition from Kon’s anime, Perfect Blue, for the painting Curb Check Regular, Black Chick touches on that taking. Understanding the source materials for my compositions is not essential to how a viewer relates to or deciphers my work, but it helps the work unfold beyond the initial interaction.

BROWN: Can you talk about the relation of your work to this lineage of cartoons and animation?

ELLIS: Cartoons are useful because they’re direct while carrying a history of cultural implication. The ways in which representation has been used to oppress black people can be touched on so quickly just by painting a white duck brown/black. We are so eager to look for those connections in the work of black artists that it takes very little to reference them. Finding commonality on what exactly these references illuminate is a much more complicated endeavor. A simple gesture can be perceived as heavy handed, denying a mark its effervescence and, in turn, a complex symbol can be brushed off as an arbitrary choice.

Janiva Ellis, Runk’d, 2017. Oil on canvas, 14 1⁄2 × 10 in. Courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Joeg Lohse.

Some of my images are perceived as overtly referencing blackface and Sambo when they are just Warner Bros. or Disney characters that I painted black/brown. I made these characters black to fit my narrative, but this gets read as directly touching on the lineage of exploitative black imagery, which I guess it inevitably does.

Because of this painful history, black cartoons have rarely been heroically portrayed to wide young audiences. This truth, for me, is not a point to be exploited or inverted, but an inescapable fact that I haven’t finished trying to understand. When my compositions (re)purpose defunct delineations of racial representation, it is as a means for complicating and obscuring existing narratives, while also communicating the dimensionality of the characters. I’m sure movies like Robin Harris and Bruce W. Smith’s Bébé’s Kids (1992) also subconsciously influence my desire to merge cartoons and blackness in a way that I can relate to.

White cartoons from Ralph Bakshi’s movie Coonskin (1975), a satirical depiction of American life and the disparity between black and white experiences, have crept into several of my pieces as a means of referencing fragility and entitlement through appropriation. The use of slurs and the continuation of black caricature is no more exaggerated by this white Italian illustrator than it is in a Quentin Tarantino movie, yet the presence of cartoons allow it to be digested as a playfully extreme racial critique.

BROWN: Being “playfully extreme,” there is a particular humor in a cartoon’s exaggeration or magnification.

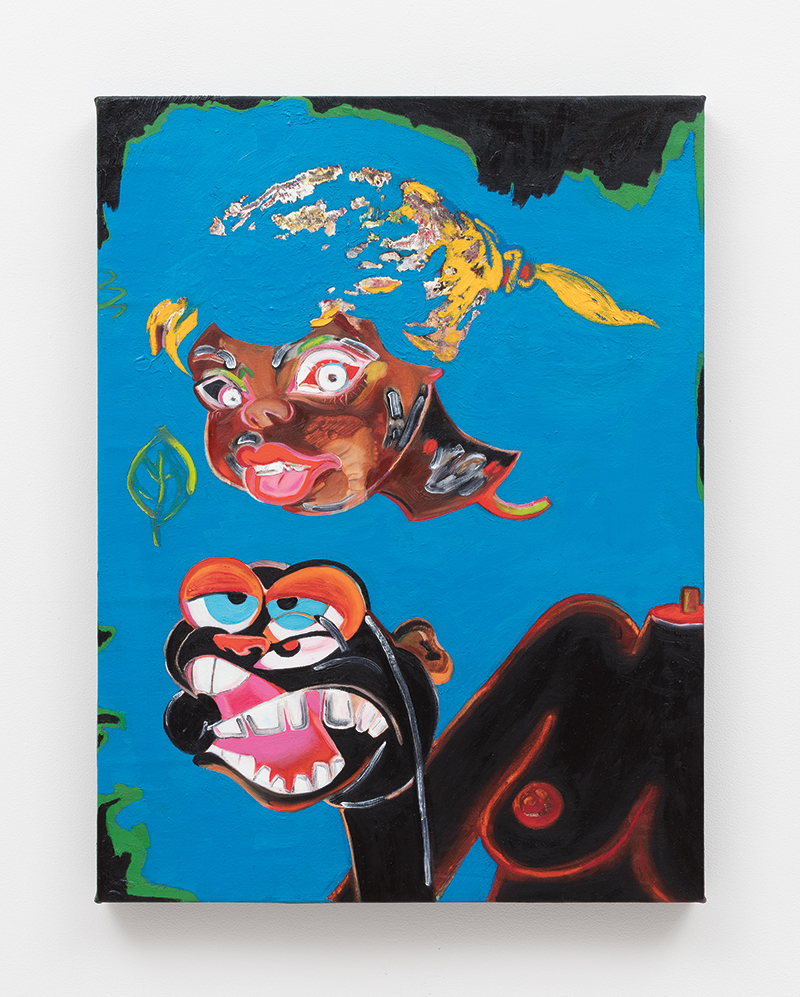

ELLIS: Exaggerating the expression opens the work in a way that allows room for both the humorous and the macabre. In Co-Panic.ing (2017), a cartoon head flies through the air while another figure rattles below. In this instance, depicting panic as decapitation is an exaggeration that implies both stress and jest. Reducing an image to these two extremes unlocks its content, inviting a variety of perspectives to relate. Works like this one seek to establish a language that functions like a gloved hand, muting its individuality yet exaggerating its gesture.

Janiva Ellis, Co-Panic.ing, 2017. Oil on canvas, 30 × 22 1⁄2 × 1 1⁄2 in. Courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

BROWN: In their exaggerated expressions, some faces appear as masks. In the past you’ve spoken about the mask as a representation of duality.

ELLIS: I’ve said “duality,” but maybe it’s more a representation of the multiplicity that occurs when we juggle who we are, how we feel, and how we are perceived. The inclination to clumsily reduce one another as either different or similar is inherited from a brutal and outdated philosophy. When appropriately contextualized, acknowledging difference can be crucial to the survival of the marginalized. When mishandled, acknowledgement of difference encourages assumptions that lead to projection. The stains of these projections can heavily influence our sense of self and alter the faces we wear.

BROWN: The mask, then, is an available form to be borrowed. How does it transform in your work?

ELLIS: My education emphasized the importance of contributing something original. Spending so much time looking at a selection of works by those who came before me as a means for departure made no sense to me as a student. Until recently, I hadn’t considered the validity of transforming things that already existed.

Information is often tailored in relationship to who is communicating and who is transcribing. Because both black and non-black histories are often broadly broadcast through a white lens, they’re distorted. I find it worthwhile to re-examine the media that informed my youth. It feels important to pile it all together and pull it apart—to understand how the narratives change as I mature, and to understand how the narratives can change when communicated by a black woman.

Janiva Ellis is a painter who currently lives in Los Angeles and New York.

Laura Brown is a writer and curator living in New York.