Neil Hamburger. Photo: Myles Pettengill.

Neil Hamburger stood before the crowd with a grotesque comb-over and a constipated scowl, managing to hold three cocktails and a microphone at once. He punctuated his jokes by making pained whimpers and huge phlegmatic coughs. Some of his jokes landed, most did not—though this may have been by design. Hamburger is a character, after all, a high concept joke about comedy created by Gregg Turkington. As Hamburger, Turkington has toured with indie bands for the better part of two decades, inciting hecklers, telling deliberately awful and offensive jokes at the expense of entertainment mediocrities like Eddie Vedder and Criss Angel, and claiming the mantel of “America’s Funnyman” for himself.

Hamburger’s stand-up set was the penultimate act of MOCA’s Step and Repeat, a month-long cross-disciplinary performance series. Step and Repeat billed itself as a “return to live art programming” at the museum, with “a special focus on the burgeoning performance communities of Los Angeles.”1 Curators Bennett Simpson and Emma Reeves assembled a roster of performers both impressive and adventurous, including experimental poet Vanessa Place and Internet celebrity multimedia artist Yung Jake. On this final night of the series, as singles mingled in front of MOCA at the taco trucks and cash bar, visitors inside shuttled from one numbered gallery to the next for performances by the poet Kate Durbin, the artists Wu Tsang, Geneva Jacuzzi, and Brendan Fowler, and an ongoing improvisational ambient guitar piece by Imaad Wasif and Jeff Hassay that was heard only through a pair of Beats By Dre headphones. Neil Hamburger followed all of this, in the lead up to the grand finale: legendary indie rocker Stephen Malkmus and his current band, the Jicks.

Installation view of Step and Repeat. Photo: Joshua White.

Gallery 4, where the comedians performed, featured a 3-foot high, grey carpet-lined platform for a stage. The open ceiling arrangement of Geffen’s galleries meant that the sound from the speakers tended to fly 50 feet above the audience, intermingling with hundreds of side conversations and the bass rumbles of the aforementioned DJs. But Hamburger was undeterred. After another joke was delivered dead on arrival, he abruptly shifted gears. “It’s great to be here folks,” he began, “… on this HISTORIC stage.” And there it was—his first big laugh.

The title Step and Repeat refers to the red carpet ritual of actors and celebrities posing for photographs in front of a vinyl banner printed with repeated logos. Naming the festival after this tacky phenomenon suggests a tongue-in-cheek glamour. Similar to MOCAtv, the museum’s ongoing YouTube-based video programming, for which Emma Reeves is creative director, Step and Repeat had a certain air of the early, anarchic MTV about it. It was spectacular but self-aware, with its stars culled from the countercultural fringes of the art and entertainment worlds, unified by a sharp graphic design (provided by Brian Roettinger).

Stand-up comedy in the white-walled context of art brings the dark side of its practice into high relief. Comedy jargon references murder and death— “killing” an audience means getting laughs, “dying” or “bombing” means getting none. The language dramatizes the often hostile and always codependent relationship between an artist or comedian and her audience. Similar to performance artists, comedians have developed a performer-audience rapport that is parallel to but separate from theatrical acting. They break and rebuild the fourth wall with fluidity, and the grammar of their craft is at least as sophisticated and nuanced as their performance artist counterparts squarely seated in the art context.

Installation view of Step and Repeat. Photo: Joshua White.

Contemporary artists have, of course, thematized comedy and stand-up, as in Mike Kelley’s Day Is Done (2005–6) and Olav Westphalen’s Even Steven (2013); they have appropriated its texts, as Joe Scanlan’s Donelle Woolford project, Dick’s Last Stand (2014); and glorified its heroes, as in Sean Landers’ Andy Kaufman (2004) and Richard Pryor (2004). But the embrace of comedians as artists in their own right seems to have taken hold in this decade. In the past two years alone, alternative stand-up comedy was featured in a number of Los Angeles nonprofit and commercial gallery spaces, including 356 S. Mission Road, Machine Project, Night Gallery, and Public Fiction (in affiliation with the Hammer’s Made in L.A. biennial).2

New York curator Miriam Katz has been a force in contextualizing comedy in relation to art, organizing several events at MoMA PS1 featuring comedy performances and discussions of “The Art of Stand-Up” and “Comedy in the Expanded Field.” Web series such as Touching the Art on the Ovation network, featuring artist/comedian Casey Jane Ellison interviewing all-female panels of curators, writers and artists, and Hennessy Youngman’s Art Thoughtz, where art concepts like relational aesthetics are explained and subtly mocked in a hip hop patois, reframe contemporary art discourse from the perspective of stylish and self-involved comedic characters.

The writing of artist David Robbins also must be credited for influencing some of the art world’s reassessment of its relationship with art. In his November 2004 essay for Artforum, Concrete Comedy: A Primer, Robbins proposes a consideration of comedy as a context neither in opposition to nor in aspiration of art, but equivalent to it. He defines “concrete comedy” as humor located in objects and in “doing things ‘for real,’” while mainstream comedy is verbal.3 Robbins contends that some things we call art, such as Duchamp’s In Advance of the Broken Arm (1915), would be more accurately described as concrete comedy. According to Robbins, “making sophisticated comedy… is the instinct of more and more young people… Many of them insist on introducing their stuff into the art context… where, too frequently, it is dismissed (not incorrectly) as inferior art when it might be celebrated instead as superior comedy.”4 This statement suggests the possibility that the misunderstood artist can become an excellent (concrete) comedian. Conversely, there is the implication that the best comedy is only as good as the worst art. One must conclude that art is somehow innately superior to comedy, which would reinforce the traditional cultural hierarchy. How would something be determined as sophisticated, and superior, comedy without privileging literary or artistic merit? The trick seems to be that within the form of well crafted object- or performance-based jokes, hoaxes, and pranks, there is an essential, self-contained elegance. Robbins locates the inadequacy of our current critical approach in addressing works that involve humor, and his concept is useful in clarifying why certain sorts of comedy, like Andy Kaufman’s intergender wrestling matches,5 (which would qualify as concrete comedy as they are a series of performances enacted within entertainment contexts, yet not strictly intended for the entertainment of those present) are more readily integrated into the art context, while others, like Jerry Seinfeld’s observational humor, (language-based, and therefore “mainstream”) are not. But Robbins’ theory does not account for the art world’s current fascination with stand-up.

Primarily, what interests me in Step and Repeat is the inclusion in the museum context of numerous comedians and performers who employ comic personae in their work. It is appropriate, if somewhat predictable, that the comedians in Step and Repeat are associated with an “alternative comedy” scene that is an experimental subculture within the greater comedy world that appeals to educated, mostly upper middle class liberals. This particular strain of comedy is more at ease within a contemporary art museum, as it has much in common with performance and conceptual art.6

Alternative comedy also thrives at comedy theatres, alternative performance spaces, and on a slew of podcasts, which are cheap to make and easy to distribute. Venues like the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatres in New York and Los Angeles keep their door prices low and pay performers virtually nothing, encouraging performers to take risks and try new things. Podcasts such as Comedy Bang Bang and The Best Show allow comedians to stretch out and improvise or perform bits for hours (literally), experimenting with pacing that would be unheard of in any other format. A school of comedians has developed who feel little obligation to make their work palatable to the average person. This unapologetically experimental spirit has bled into television and animation.

Derrick Beckles at Step and Repeat on September 20, 2014 at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Myles Pettengill.

Many of the shows on Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim block of programming are natural extensions of the critique and dissection of television that was initiated in eighties video art, such as Michael Smith’s Secret Horror (1980) and Joan Braderman’s Joan Does Dynasty (1986). I’m thinking of the Adult Swim shows Tim & Eric Awesome Show Great Job! and the now defunct Xavier: Renegade Angel and Wondershowzen.7 More recently, Adult Swim‘s synthesis of stoner humor and video art critique of the sitcom reached its apotheosis in Too Many Cooks, an eleven-minute short which spoofed not only eerily uncanny-yet-goofball shows like Alf and Diff’rent Strokes, but also the suburban terrors of David Lynch and Dara Birnbaum’s remixing of television in her 1979 video Technology/Transformation: Wonderwoman. Today, Birnbaum’s art of subversive remixing finds its comedic analogue in Step and Repeat performer Derrick Beckles, whose TV Carnage series of tapes and DVDs uses found footage from local TV, cable access, and infomercials as raw materials for extended compilations edited to maximal dislocating effects.

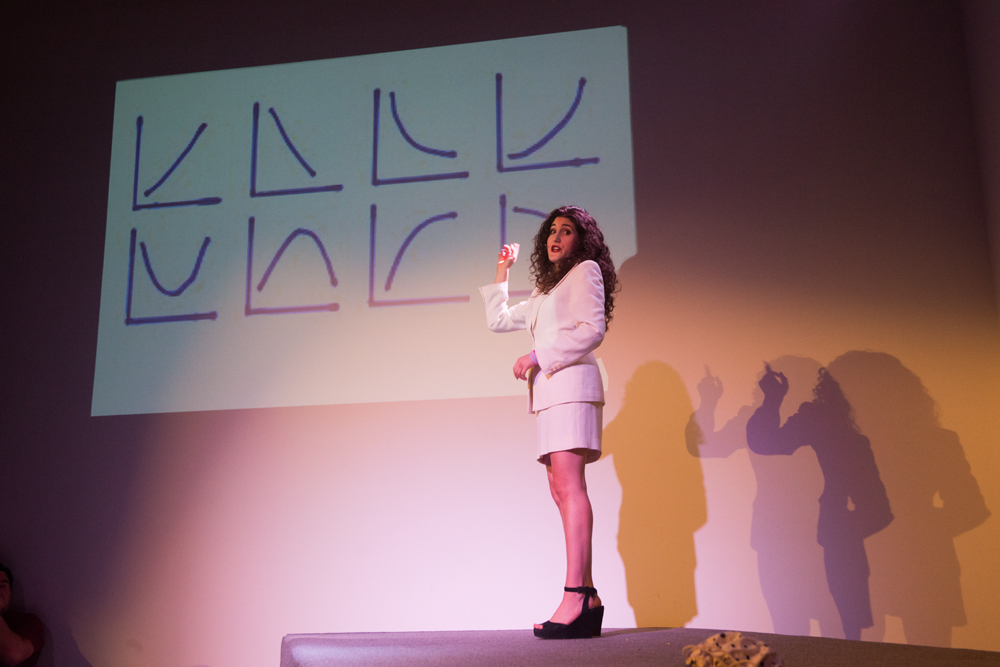

Comedians usually develop work under the assumption that it will be performed in the context of a nightclub (The Comedy Store) or a black box theater (Upright Citizens Brigade Theater, Largo). This is significant, as the black box, meant to minimize critical distance and maximize audience identification with the performer, is an inverse of the white cube. The comedian best able to address the art world context at Step and Repeat was Kate Berlant, and she absolutely killed. Berlant played the role of a life coach prone to pointless sidebars. An expert public speaker, her character had a mastery of the affected tone and throwaway jargon of habitually bracketing academics and entitled TED Talkers who neglect to provide any message. Berlant supplemented this character with a PowerPoint slide show, a brilliant stroke of multimedia redundancy. Images of things like a dog wearing blinders added flashy visual support to her empty platitudes. According to David Robbins’s criteria, Berlant’s persona may be a candidate for the designation as concrete comedy. Although her stand-up is language-based, it’s also contingent on her inhabiting a certain persona, and her message is engendered in her actions rather than the text. The text is a texture or backdrop for the acting out of the pathologies of the character.

Kate Berlant at Step and Repeat on September 20, 2014 at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Josh White

Like many in the Step and Repeat audience, she was well-educated (she graduated with a self-designed major in “the cultural anthropology of comedy” at NYU’s Gallatin program)8 and emanated millennial confidence. Her persona at MOCA fed into the self-improvement ideology of the upper middle class. People go to museums to improve themselves culturally, and this performance rewarded that effort by satirizing it. Berlant got her start performing in galleries, eventually graduating to comedy clubs. Recently, she has been gaining notoriety as a comedian, while collaborating with artists such as Natalie Labriola on video works for MOCAtv. In an interview with Pete Holmes on his podcast, You Made It Weird, she explained that her start in the art context was a result of her trepidation about performing in clubs.; “I [thought] I’m gonna . . . do my comedy in, like, galleries… [but] that’s not what I wanted. I felt like a stand-up.” 9

Another performer whose reception rivaled Berlant’s is Dynasty Handbag. Dynasty Handbag is the alter ego of Jibz Cameron, a performance artist and actor based in New York. Cameron has performed as Handbag for nearly a decade, while also working with a number of theater companies, including the Wooster Group. Though Cameron’s milieu is more that of experimental theater, video and performance art, Dynasty Handbag is a comic persona. Her performances deal with heavy subjects like dysfunctional family, gender issues, queer identity, and depression, but she rarely stays in a dark place for long before popping out in manic, angular glee.

Dynasty Handbag at Step and Repeat on September 20, 2014 at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Josh White

Dynasty Handbag feels like electro-provocateur Peaches mixed with Amy Sedaris’ reformed prostitute high school student Jerri Blank from Strangers with Candy. During Step and Repeat, Handbag traded her usual practice of wearing a bathing suit on top of elastic stretchy pants for a more Bob Fosse-style. She had on a wide-brimmed hat and her signature extreme eye makeup. She pantomimed finger banging a mic stand and wended her way through a set of deconstructed musical comedy that included stand-up-style crowd work, coiled and defensive Gollum-like hissing, a karaoke pulverization of an insipid Beyoncé song, and some self-deprecating pleas for donations to her Kickstarter campaign.

Jibz Cameron operates from a queer feminist perspective. As an alter ego, Dynasty Handbag can be used to expurgate toxic emotions and impulses that develop as a response to marginalization. Anger, frustration and self-sabotage can be performed and sublimated within her constructed identity. What’s more, they can be disempowered, and turned into glee. Similarly, Neil Hamburger’s crass and offensive jokes about mediocre bands and French mimes are a screen through which Gregg Turkington’s rage about the undignified and poisonous character of contemporary life can emit full force. Kate Berlant’s laughable figure of unassailable self-possession and infinite digression is a comment on our collective fear of direct communication.

Although I enjoyed several of the comedy performances at Step and Repeat, I found it difficult to assess their merits within an art context: Is it successful when people laugh, or more successful (as art) if the comedians bomb? One could argue this insistence on distinguishing one métier from another is counterproductive; the whole point is that the performers in Step and Repeat blur the lines. But, I can use the history and established identities of the comedians to make judgments about their performance. For example, “Neil Hamburger” is more complex because I know the middle-aged guy telling bad jokes is part of a twenty-year durational performance piece that started out as a young guy dressed up as a middle-aged guy telling bad jokes.

Neil Hamburger at Step and Repeat on October 4, 2014 at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Josh White.

Stephen Malkmus and the Jicks at Step and Repeat on October 4, 2014 at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Myles Pettengill.

As art institutions are required to become more self-sustaining, elements of entertainment and pop culture will further integrate into their programming. We may be looking at a future where the contemporary art museum becomes a showcase for culture in general, rather than visual arts in specific. At the same time, the Internet (through websites like Tumblr and YouTube) has radically revamped the distribution of images and video, putting visual art, experimental film, and performance documentation on equal footing with literally any iteration of image and video that can be pixilated and posted. The result is a generation creating work with little regard for established cultural hierarchies. Still, the art context has the advantage of requiring no inherent commercial potential to validate any given pursuit, so creative people working in uncharted territory of every medium will find themselves identifying as artists by default. Museums, in turn, are expected to uphold some standard of quality. In theory, anything within their walls, if not art per se, has been deemed worthy of archiving and preservation, and is therefore culturally significant enough to be taken seriously. Even if it’s a joke.

John P. Hogan is an artist based in Los Angeles.

ADDITIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Philip Auslander, Presence and Resistance. Postmodernism and Cultural Politics in Contemporary American Performance. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1992.

John Limon, Stand-Up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2000.

Albert F McLean, Jr., American Vaudeville as Ritual. University of Kentucky Press, 1965.