A Very Brief Itinerary

In a moment of blindingly abject clarity, an anonymous someone condensed a number of not-quite-trenchant comments into a brilliant descriptive aphorism now indelibly attached to the name of Frank Lloyd Wright: “Tip the world on its side and everything loose will land in Los Angeles.”1 “Everything loose” included me: Washington, D.C., suburban northern Virginia, New Haven, New York, Boston, Providence, South Orange, Berkeley, Oakland, Albany, Marin County, Eureka, Athens, London, Dallas…and Hollywood. It was like a dream come true, living in a renovated apartment on Franklin Avenue, just about halfway between Welton Becket’s Capital Records Tower (half a block up from the fabled intersection of Hollywood and Vine) and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House crowning the hill in Barnsdall Park, below which I used to catch the #754 bus for the long ride down Vermont Avenue to Exposition Park and my job at the University of Southern California.

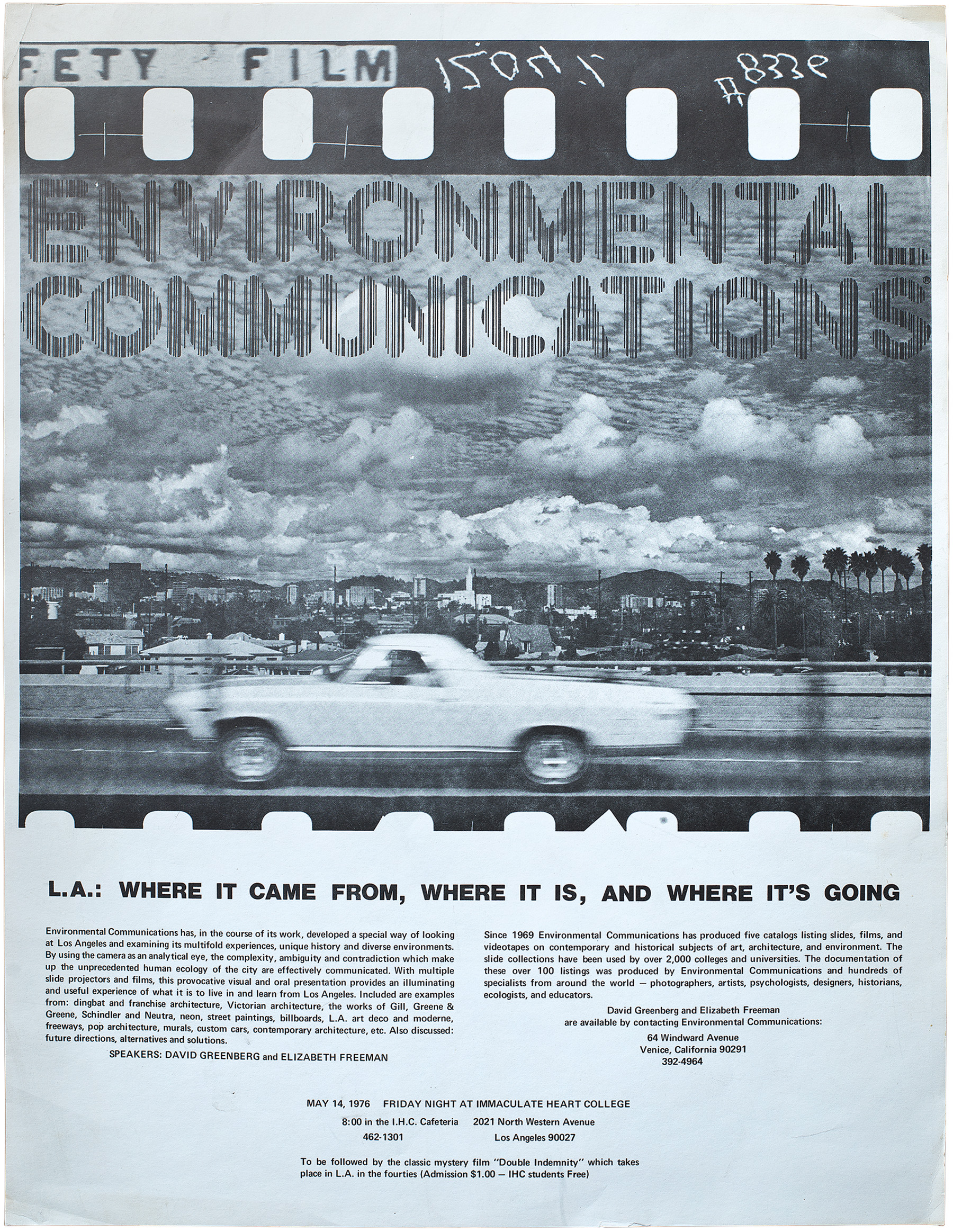

Environmental Communications, Poster, 1979. Poster, 22 1⁄2 × 17 1⁄2 inches. Courtesy of David Greenberg. Photo: Mark Escribano.

By the time I began that trek—followed eventually by endless swings from Westwood or Santa Monica east along the I-10, through the Downtown Slot, up the 110 to the Pasadena Freeway and my new home; or equally endless and excruciating chugs up the 405 through the Sepulveda Pass, east across the (San Fernando) Valley via the 101, the 134, and the 210—Los Angeles had already become firmly established, both conceptually and actually, within the world of post-modernity. The trajectory of that passage, which can be charted from the late sixties through the whole of the 1970s to a moment of relative stasis round about 1980, has been magnificently laid out in the exhibition Everything Loose Will Land: 1970s Art and Architecture in Los Angeles, recently on view at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles, at the Schindler House on King’s Road. The exhibition was curated by Sylvia Lavin, director of critical studies and MA/PhD programs in the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at the University of California, Los Angeles.

L.A. Is Truth2

But Truth has a way of being damnably complicated and maddeningly unforthcoming.

In the case of Los Angeles, we can perhaps begin with the following two-pronged observation: the term postmodernism can be applied productively both to individual buildings, in the same manner it might be applied to characterize individual literary texts, and to a complex process of thinking, representing, and (en)acting architecture as a whole.3 And in the latter case, the literary comparison might be drawn both to the making of things—an authorial function—and to their analysis, what we might call a critical or a “readerly” function.

Within a broadly academic context, John Portman’s Bonaventure Hotel (1974–76) is usually identified as the iconic postmodern building, thanks in large part to the brilliant analysis put forward in Fredric Jameson’s now-classic Marxist study of the cultural logic of late capitalism.4 Briefly, Jameson sees the Bonaventure design as consciously disrupting traditional design and planning expectations, to the extent that the building becomes detached from the urban fabric of the street and thus comes to constitute its own interior as a kind of disorienting Hyperspace within which the building exists as a virtual city within the actual Los Angeles, like one of Italo Calvino’s “Imaginary Cities,” or the destination of one of Umberto Eco’s “Travels in Hyper-Reality.” But Los Angeles can produce postmodern architectural icons with almost the same facility as it engenders stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. For example, the cover of the 1985 edition of David Gebhard and Robert Winter’s authoritative Architectural Guidebook to Los Angeles carried a photo of the Getty Villa at Malibu (1972–73), which the authors described on the back cover as the one “must see” building in Los Angeles: a perfectly glitzy, retro example of postmodernism as an architecture of radical quotation and re-appropriation. But, as time marched on, history, even almost-contemporary history, was reinscribed. Thus, the 1994 edition of the guidebook illustrates on its cover the more radical yet cleverly subtle Chiat/Day/Mojo Advertising Agency (1985–91) by Frank O. Gehry and Associates with Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen. Finally, the current (2003) edition—surely already in need of revision—has settled on a new and doubtlessly enduring icon: the swelling, fluid, and decidedly sculptural mass of Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall.

Everything Loose Will Land, installation view, MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles, at the Schindler House, 2013. Photo: Joshua White.

It is, however, not the status of any individual building but rather a set of signifying processes that informs the conception of Everything Loose Must Land. These processes are grounded in a (seemingly) endless recirculation of representations, brought into ever-changing constellations or patterns of juxtaposition and driven by evolving structures of global capitalism. On a more mundane level, they condition the exhibition’s structure, guide the selection of objects, shape their presentation, and in the end produce a brilliant re-examination of a decade that saw an unprecedented (and so far unrepeated) cultural and artistic cross-fertilization. The show suggests, to me at least, a moment not just of untrammeled freedom, but also of profound uneasiness and transformation, when one world (at least) was irrevocably left behind, while others coalesced to form configurations not just new, but also unimagined. We can cover that coalescing world under the rubric postmodernism.

Dearchitecturization5

As an exhibition, Everything Loose Will Land was organized in four sections: Procedures, Users, Environments, and Lumens. The material displayed in each of these sections was intended to characterize a salient aspect of the relationship “between building[s] and architecture” which, at least during the 1970s, defined “what distinguish[ed] the world itself from its cultural systems.”6 In particular, this involved a rethinking of the set of more-or-less determinate rules governing the processes of architectural planning and construction. These now came to be seen as a set of open-ended systems that governed resource allocation and distribution, environmental interfaces, the relationship between architect and client, and a reconfiguration of space as environment.

The exhibited material was masterfully selected and tightly presented within the intimate modernist space of the Schindler House. As a result, the experience of the show was both expansive in scope and personal in feel. Furthermore, it was wonderfully balanced. While some of the selected objects were expected simply by virtue of the show’s demonstration of those striking and seemingly endless intersections, juxtapositions, interpenetrations, revisions, and re-conceptualizations that comprised its thematic, much was equally relevant yet quite unexpected. In some cases, Lavin and her collaborators were able to bring to light material never previously published or exhibited; in others, it was not so much the character of the exhibited objects themselves but rather the way in which they were brilliantly recontextualized that encouraged us to see them in a new and strikingly different light.

The circumstances of the set-to between Ed Ruscha and Frank Gehry concerning the “authorship” of Ruscha’s 1977 Santa Monica house and studio are apparently well known within architectural circles, and perfectly illustrate the collapse in the 1970s of traditional notions of the relationship between client and architect. Always the “Stud,”7 Ruscha was a compulsive collector of architectural fragments and an inveterate DIY designer and builder. He seems to have considered Gehry as essentially a private contractor, providing what amounted to anonymous professional services. Needless to say, Gehry’s understanding of their putative relationship was rather different. We would expect the exhibition to touch base with this controversy, and it does; but what is surprising is the character of the visual material that illustrates this episode: not just a wonderfully scribbly sketch from Gehry’s own hand (one can almost see the architect turning ideas over in his mind as he works over the drawing again and again), but also a pair of beautifully finished drawings (plan and elevation) painstakingly produced in the Gehry office.8

Equally surprising, if in a quite different way, was a 22-minute video composed of a single two-shot framing the heads and shoulders of a pair of young, attractive, intense-looking intellectual types. One, a rather stand-offish young woman, was berating her male companion, in a relentless parody of pseudo-theoretical New York culture buzz. Her opposite number parried with a brilliant riff on stoner L.A. art rap worthy, almost, of Thomas Pynchon. The interlocutors, of course, were Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson in their video, East Coast, West Coast (1969). Watching their performance brought me up short against the extremely thin line that can divide legitimate, theoretically informed discourse from its Alice-in-Wonderland doppelgänger. It also served to remind me of my own recurrent unease with both Holt’s East Coast and Smithson’s West Coast stereotypes, but it didn’t seem to have much to do with architecture.

The catalog commentary, however, proposed that the video did in fact serve an immediately relevant purpose: namely, to draw attention, if a bit obliquely, to the idea of a fluid or flexible “system” (conceptual, discursive, practice-oriented) “that had become increasingly central to Smithson’s art and writing by the late 1960s and that made his work available to architectural thought, even in unintended ways.” One example discussed in the catalog is the ill-fated Portland Cement and Kaiser Steel Projects (both 1969) undertaken as part of the Los Angeles County Museum’s Art and Technology program.9 It was a telling moment in my experience of the entire show: matching my first immediate experience of a soi-disant anonymous video fragment against a more reflective and self-conscious re-viewing of the entire authored and unfolding argument. And it was also a telling demonstration of the brilliantly interconnected structure of the exhibition.10

Works on Paper

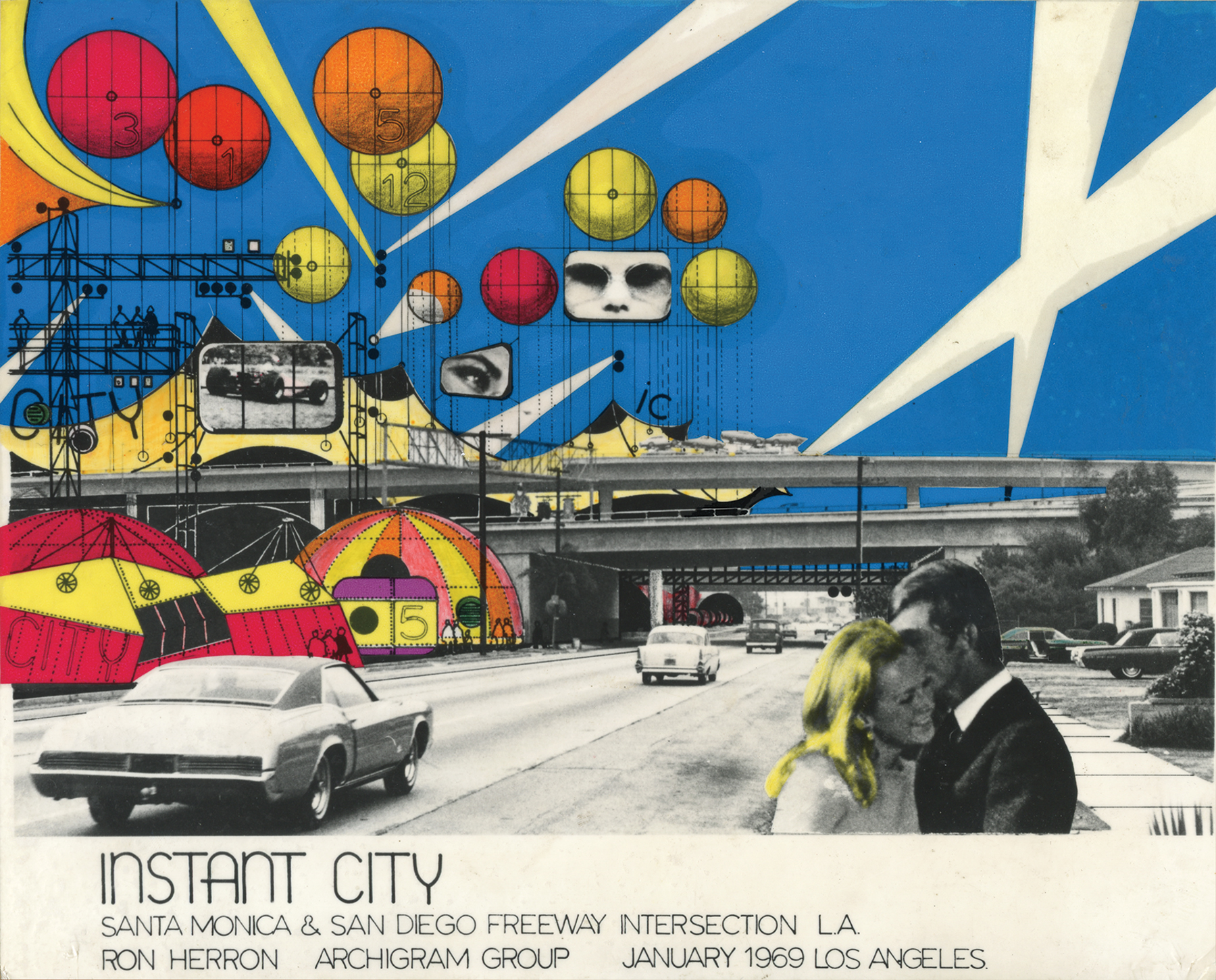

The catalog both recapitulates and amplifies this basic conception so that it becomes both an essential companion to the exhibition and an invaluable resource for future research. In some ways, its organization is standard: an introductory essay by Lavin provides a general context and introduces the exhibited material under its thematic rubrics; and an annotated checklist of the objects in the exhibition, compiled by Lavin and a dedicated group of students,11 provides very specific archival context within which to situate individual objects, many of which have never before been exhibited. I will return to the introductory essay below; here, let me just say that the annotated checklist is exceptional, and represents a real and valuable addition to our knowledge of an extraordinary group of artifacts, as well as a serious contribution to the discourse around postmodernism, Los Angeles architecture, and the visual and architectural culture of the 1970s in general. In addition to the introductory essay and checklist, the catalog also contains a series of short but concise essays focusing on particular objects, conceptual orientations, processes, and institutional contexts subsumed by the exhibition: Ed Ruscha’s Thirtyfour Parking Lots (1967), Archigram in Los Angeles (the whimsical mega-structure Instant City, 1969), Womanhouse (1971–72), Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison’s Shrimp Farm (1971), and the architectural interfaces of Light and Space (the key period covered is 1966–68, and the artists include James Turrell, Doug Wheeler, and Larry Bell). Written by Susanna Newbury, Simon Sadler, Peggy Phelan, Margo Handwerker, and Alex Kitnick, these essays are erudite and provocative throughout, and provide invaluable contextual and interpretive material.

But what really makes the catalog unique is a long central section printed on goldenrod-colored paper. It is titled simply “Works on Paper.” As the curator explains, “This section of the catalog is conceived as a supplementary gallery for works on paper, or rather for works on more than one sheet of paper…from hand-written letters to mass-market books and from informally produced production manuals to artists’ notebooks. …As a result, certain kinds of material that challenge the conventions of museum presentation were included here…where they can be seen in their entirety. Each item is reproduced as close to natural size as possible…” In other words, what we have is a mini-gallery of facsimiles (the idea is pure genius) that reduplicates and “glosses” the show, but that can be examined at leisure (most of them are, after all, fairly text-heavy) without overly burdening the initial viewing experience. In addition, each entry is provided with a brief introductory text, providing information on original source and context. Thus, we can compare, for example, Billy Al Bengston’s classic photo essay on Los Angeles artists’ studios12 to Ed Ruscha’s not-so-classic Design Quarterly exercise in “conceptual architecture,” “Five 1965 Girlfriends.”13

More substantially, consider the evolution of Womanhouse. Again, the basic circumstances surrounding this groundbreaking feminist collaboration, developed under the supervision of Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro, are well known. The project is represented in the exhibition by two versions of the exhibition catalog, designed by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville in 1971.14 This brief notice is supplemented by a more extensive discussion in the curator’s essay, which focuses on Womanhouse as an iconic piece of DIY architecture, and in a perceptive and challenging essay by Peggy Phelan. Phelan, in particular, discusses Judy Chicago’s “flawed” essentialism of the early 1970s, which Phelan sees as manifesting a confusion of the logic of serial structures common to Minimalism with the more complex (and, at least by implication, politicized) “structure” of the female body. At the same time, she describes the finished collaboration under yet another rubric: “[I]n its three-month existence, Womanhouse realized architecture as a mode of live performance….”15 Even this brief survey should be adequate to demonstrate how the catalog works not only to place Womanhouse on its own footing, but also to relate it to any number of other structurally similar if conceptually divergent projects, from Peter and Clytie Alexander’s 1973–74 House at Tuna Canyon to the “public service” architectural interventions of “The Studs” (especially Billy Al Bengston and Ed Ruscha), and even to Allan Kaprow’s brilliant 1967 performance/installation Fluids.

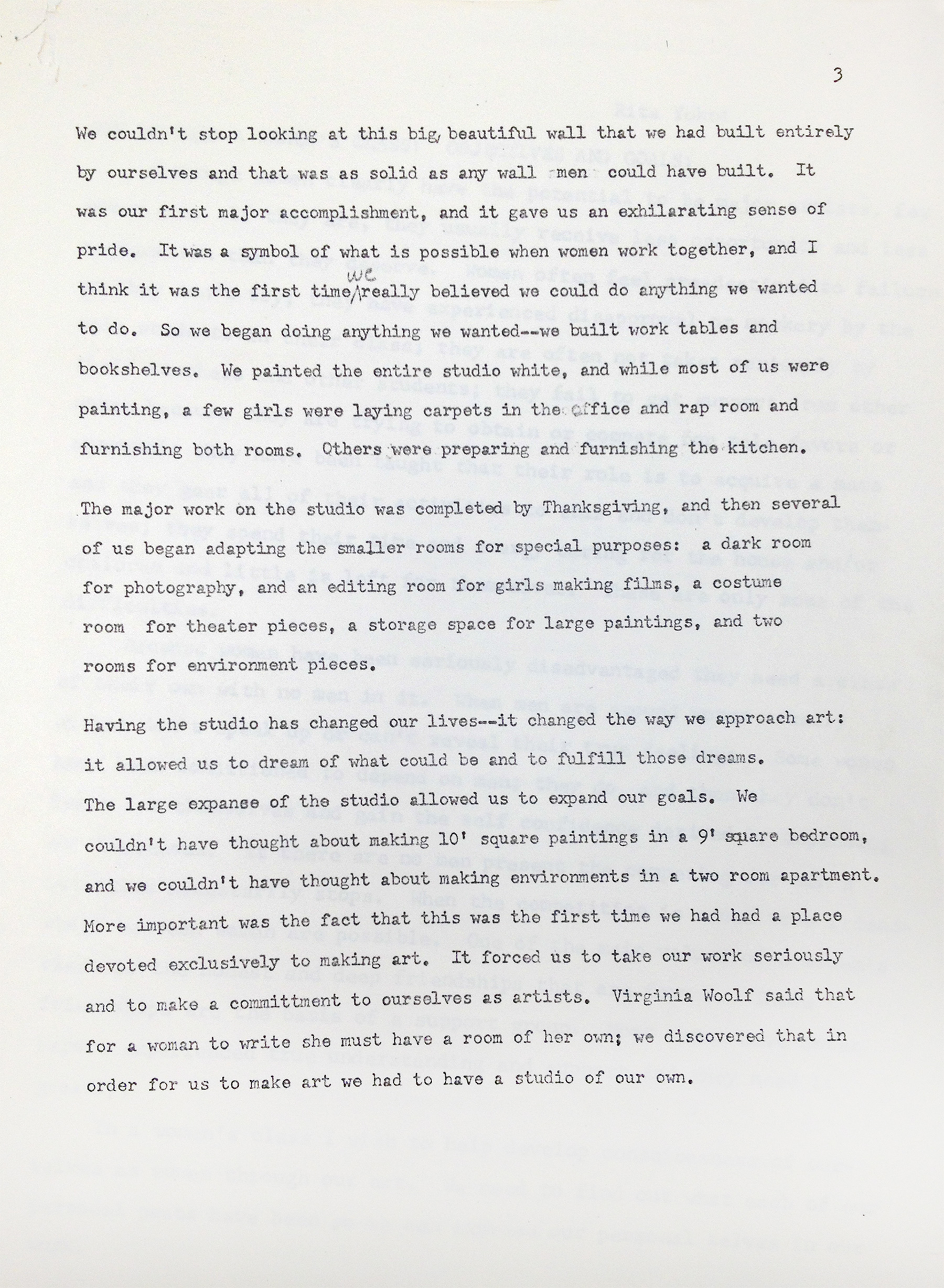

But beyond this, our understanding of Womanhouse not only as a work with a conception, a history, and a context, but also as a project articulating lived experience is provided by the inclusion in “Works on Paper” of an extraordinary unpublished manuscript, “Building the Studio,” written in 1971 by Janice Lester.16 Lester had been involved in the Feminist Art Program since its inception at Cal State Fresno; and her essay addresses the program’s first building project, undertaken in Fresno. This project later provided the “blueprint” for Womanhouse, which itself morphed into the even more ambitious Woman’s Building. Although relatively brief, Lester’s text provides a beautiful sense of the genesis of the original project in an art school atmosphere redolent with the “fear of psychic or physical invasion” and the “lack of the kind of psychic privacy necessary to function creatively.” (At this point, Lester still refers to herself and her fellow students as “girls,” who each agree to kick in “$20 a month” to get things going.)17 Later, having mastered both their fear and the intricacies of the necessary power tools (a skill set previously reserved exclusively to “studs”), she relates: “We couldn’t stop looking at this big beautiful wall that we had built entirely by ourselves and that was as solid as any wall men could have built. …[I]t gave us an exhilarating sense of pride. It was a symbol of what is possible when women work together.”18 Beyond any retrospective analysis or evaluation, this first-person narrative makes real and palpable a profoundly empowering transformation of the sort often associated with more abstract-sounding terms like “consciousness raising.”19

Janice Lester, Building the Studio, 1971, unpublished manuscript, pp. 1–3. Courtesy of Jan Lester Martin.

A Cottage on the Beach at Santa Monica20

The entire thrust of Everything Loose Will Land seems concentrated on understanding a particular moment of architectural postmodernism in terms of the interconnected processes around “dearchitecturization.” And if it sees Los Angeles as an array of ecological and cultural interfaces that provide a privileged site for the identification and disentangling of these processes, it also (and quite forcefully) presents a contrary case, primarily through another series of texts reprinted in the “Works on Paper” section.

This case challenges the analysis embodied in Reyner Banham’s classic book Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971), which Banham claimed was a reading of Los Angeles “in the original,” i.e., as a reflection in the rearview mirror of a car speeding along the freeways.21 (Paradoxically, Banham purports to take a moderate and thoughtful view of a city and a culture “where only the extreme is normal.”22) His critics see this text as a naive and ill-informed mis-reading of Los Angeles.23 The most vehement of these critics is Peter Plagens. In the early 1970s, Plagens was a writer based in Los Angeles, and he brutalized Banham’s book in an extensive review that appeared in Artforum in 1972.24 Although, in comparison to that of some of his contemporaries, Plagens’s review might best be described as gonzo-lite, it has its share of (gratuitous) profanity, no-holds-barred commentary, and vicious ad hominem put-downs, which are often attached to Banham’s unfortunate tendency to malapropism. But the review has plenty of substance as well.

Ron Herron (Archigram), Instant City, Santa Monica and San Diego Freeway Intersection, 1968. Collage, photographic print, ink, letrafilm on board; 8 × 10 inches. © Ron Herron (Archigram). Courtesy Simon Herron.

In her introduction to Plagens’s review, Lavin quite rightly perceives in Banham’s approach to Los Angeles an “ironic stance” (which she describes as being unacceptable to Plagens in the world of “real-life” architecture).25 Perhaps as a result of my own less rigorously academic approach, I have been most immediately drawn (both in the early 1970s and on repeated re-readings) to Banham’s obvious enthusiasm for his subject and his palpable, if occasionally disconcerting, exultation at discovering a whole new world.26 A similarly untrammeled joy is woven throughout Denise Scott Brown’s handwritten letters, also reprinted in “Works on Paper.”27 For Banham (an Englishman) and Scott Brown (an Easterner originally from British southern Africa) the West in general, and Los Angeles (and Las Vegas) in particular, must have seemed an almost magical realm. Still, these responses—Banham and Scott Brown’s joy at discovering both the possibility and the reality of an ironic built environment and Plagens’s disgust at a perceived confusion between built environment and Architecture with a capital “A”—are not, I think, entirely unrelated. Furthermore, taken together, they point toward a difficult conundrum. If, as Plagens argues, architecture by its very nature as “reality” must eschew an ironic stance, then, almost by definition, it cannot exist in, let alone define or characterize, a culture of the postmodern.28 It must simply “be,” but cannot “represent,” since representation by nature always involves a certain ironic displacement, and it is from such reiterated displacements that the endless circulation of signification that constitutes postmodernism is generated. This result strikes me as sheer wish fulfillment.

On a more practical level, Plagens takes Banham to task for his assessment of the Los Angeles freeway system, which Banham describes as unique in its ability to traverse an unparalleled collection of varied ecological landscapes with their attendant and equally varied racial, ethnic, economic, and cultural ecologies. The substance of Plagens’s critique, and its relationship to the theoretical and practical aspects of the argument at which it was directed, is much too complex to assay here. Essentially, what is wanting is a comprehensive and historically grounded re-reading of Banham’s fundamental text, as well as a point-by-point dissection of the counter-arguments put forward by Plagens, Barry Commoner, Bernard Tschumi, and others,29 supplemented by additional contextualizing comparisons drawn from across a wide intellectual and cultural spectrum.30 Fortunately, Everything Loose Will Land has provided an excellent “ground zero” from which to start.

Bruce Nauman, Untitled (Equilateral Triangle), 1980. Installation view, Everything Loose Will Land, MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles, at the Schindler House, 2013. Photo: Joshua White.

In the meantime, even Denise Scott Brown could not have imagined the circuitous line that would eventually run from her emerging notions of a built, if de-architectured, environmental ecology to Bruce Nauman’s uncannily (de-)re-architectured sculptural installation, Untitled (Equilateral Triangle) (1980). Nauman’s massive sculpture, reconstructed in the MAK courtyard, provided both a stunning end to this jewel of an exhibition and a fitting and equally disorienting pendant to John Portman’s Bonaventure Hotel.31

Glenn Harcourt is an art historian and frequent contributor to the pages of X-TRA. He lives in Pasadena, but visits Truth frequently in the course of his work.