One Tuesday evening in the Yale painting critique, where I was moonlighting as a Visiting Critic, I described a student’s paintings as “truly weird.” A moment later, another teacher said, “To tell you the truth, this soft talk drives me crazy.” Leaving aside for a moment the ideology buried in the implied conflict between hard (good) and soft (crazy making), I want here to discuss critique as a theory and a practice, and to suggest that this thing dismissed so flippantly as soft talk might be a precious and productive resource.

One of the key elements of critique is the structural opposition between interpretation and judgment. What we do at art school is to work towards becoming better artists, and making better art. Yet who defines what better art is? The authority figures—critics, curators, teachers, grant-giving bodies? The market? The dealers and the collectors? We can all think of examples where the art market seems to have been completely off in its assessments of value, where the authority figures seem out of touch and out of date. So what makes a better artwork?

The spectrum of success and failure does not hinge on the predilections of the critic or the pressures of the market; on the contrary, the success of a work is determined by the parameters set within the work itself. These parameters take form in specific elements, and we need to discuss and articulate how the artwork functions, what seems to be operative, what meanings emerge. Otherwise judgment (this worked, that didn’t) seems to me like a power move, where I get to be the authority figure, and I get to say it’s good, or better, or you’ve made progress, or you haven’t.

We all unconsciously wish for authority figures; on some level, we want to believe that somewhere there is one who knows, one who can guarantee and validate our identities and our practices. But this is an illusion: the one who knows doesn’t exist. Institutional structures tend to participate in this illusion, and to invite our participation. Within this framework, it is understood that there is something reassuring about hierarchies. Someone will judge your work, and it may be a harsh judgment this time around, but the basic structure (that there’s an authority somewhere—in New York, perhaps—who knows what’s good and what isn’t) is sustained. The structure itself is a comforting illusion.

To work towards undoing this hierarchy is to create a situation that is much more unsettling—indeed, it can be a harsh awakening, opening up a radical space of uncertainty and vulnerability. At the same time, the artist may have deep respect for specific individuals, quite apart from their institutional authority, and that gives their words greater power. While it’s a struggle for all of us to maintain a discourse constructed around uncertainty and vulnerability, ultimately I think it’s more generative and more sustainable.

There are times in the critique when we want to make specific suggestions to the artist, or to make an evaluation. In this context, however, we are invested in the critical conversation, allowing complexity and contradiction through multiple voices, and so we put aside this advice for another time. Because otherwise it’s cluttering up the task we are doing together there, which is to encounter and engage the work as it stands.

We engage the work on its terms by figuring out what those terms might be, and the work has to give us cues and clues, the instruments through which we engage it. It provides us with built-in affordances, handles to grasp, sequences to follow. Sometimes we find ourselves thinking about what the intentions of the artist might have been, as evidenced in the form and content of the work in front of us. I believe we engage in a creative hypothesis when we do this, imagining a hypothetical artist with hypothetical intentions. I don’t believe it’s particularly interesting or productive simply to ask the actual artists what they were thinking about, for a number of reasons, including the fact that they are not the best authority on their own work.

In my view, one of the points of this conversation is for the artist to find out how the work is operating: what meanings does it manifest? Are people moved by it? Does the artwork present its built-in affordances in a way that allows the curious and engaged viewer to interact with the work on its own terms? Asking the artist to tell us what she was thinking about may merely short-circuit both our process of discovery (which takes time and thought and rigor) and the possibility for the artist to find out what her artwork is doing.

Another reason not to treat artists, or anyone, as authorities on their own work is the existence of the unconscious, as well as the existence of social forces (ideology) in the form of discourses that flow through all of us, all the time. In other words, we’re not in complete control of the meanings our works produce. Whatever we intended to put out there is exceeded by our unconscious thoughts and wishes, as well as by our social construction as subjects within discourse. Our autonomy as meaning-producers is informed by systems of representation and power that we did not invent and we do not control, and these systems are at work within us.

As artists, we may try as hard as we possibly can to control the meanings our artworks produce. At the same time, we acknowledge that we may have unwittingly materialized some other things that we did not consciously intend. We might inadvertently manifest class privilege, for example, or a wish to intimidate or impress; our work might display unconscious bias, or it might reiterate and repeat the racism of our world. The work may disclose our unconscious desires about our mother, which we thought we’d resolved some time ago. Or the work may address questions we weren’t aware were in the mix, but in a positive way: it may expose relations of power in ways that propel viewers to question preconceived ideas, or produce a new awareness. In other words, the artwork always manifests unconscious intentions. The critical conversation allows for these unintended meanings to be discovered, as together we explore the ways the artwork is operating, the multiple meanings it generates, and the effects it produces.

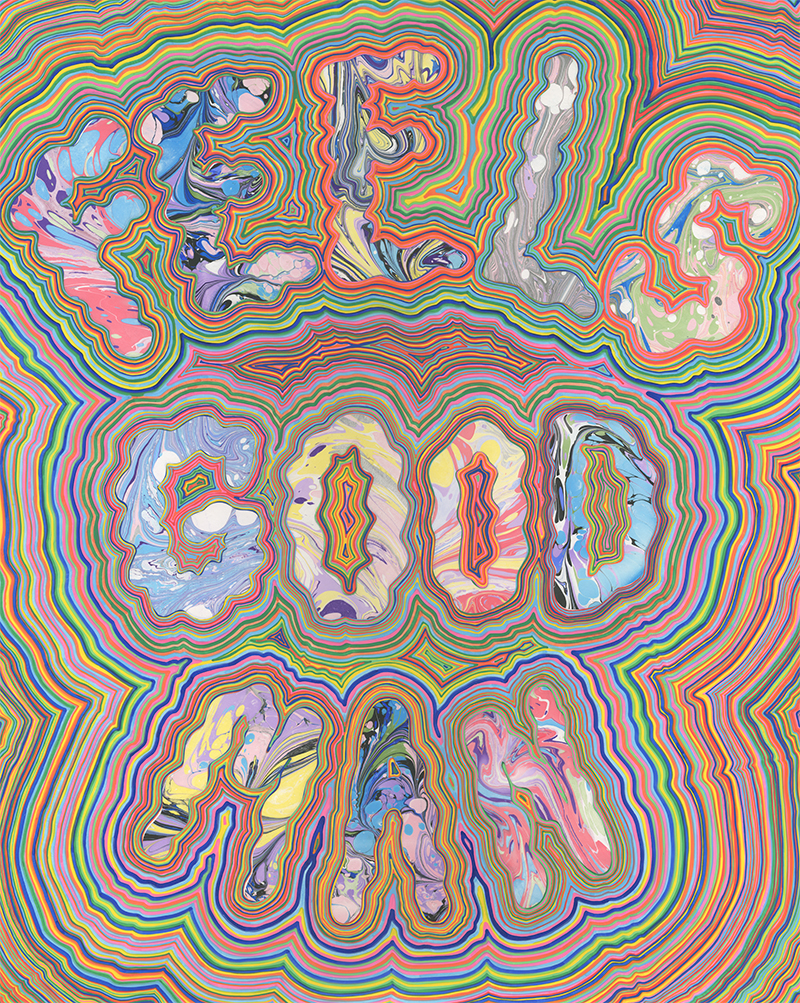

Alice Lang, Feels Good Man, 2017. Marbled paper and acrylic on paper, 19 x 24 in. Courtesy of the artist.

In this process of interpretation and discovery, we must presume that every artistic decision that the artwork presents was (so to speak) intended. If we imagine that some things about the work are merely a mistake, then we protect ourselves from the obligation of actually engaging the artwork as it exists. Our task isn’t to wonder about what could have been done differently, but rather to interact and engage with the work in front of us, and therefore to assume that the work is the most compelling work it can be. Assuming that some of the elements in the work are simply a technical error (or an error of judgment on the part of the artist) allows us to sidestep the task of describing and understanding how those elements operate.

It is much more challenging to assume the best of the artwork. It is harder to begin by defending the work. In my view, anything that seems like a technical failure is better approached as a formal element in the artwork. I try to look at the work as if it’s already valid, or already accepted as a successful artwork. That helps me get past my preconceived ideas of what a successful artwork looks like.

Sometimes when I’m grappling with understanding how an artwork is operating, I think about how the artwork proposes a viewing subject (a position from which the artwork may be viewed and, so to speak, understood) that may not coincide with my actual subjectivity. In viewing, I temporarily occupy the subject position of the ideal viewer of this artwork, in order to engage it. Then I step outside that perspective, to bring those perceptions into my own subjective field.

When I engage the artwork in this way, inevitably I find myself wondering about the artist’s intentions. In doing so, I am constructing a presumed artist, imagining a maker who had intentions, who may in turn be a fiction, an inauthentic persona constructed by the actual artist, whose subjectivity exceeds this position. In other words, just as I temporarily occupy the subject position of the viewer, and then regain my own complex and contradictory subjectivity, so too does the hypothetical artist, who makes a work that implies the subject position of the maker, and then moves on to make another work, which may imply a radically different position and point of articulation.

We are aware that we are not dealing with actual people here: we are dealing with implied, temporary positions, projected by the artwork, in order to discuss the work in a zone of hypothesis. We ask: what if the artist intended us to think or feel this? We don’t check with the actual artists here, even if they’re in the room. We check with the artwork, to see if it holds the formal and material elements that would produce that thought and feeling. The question becomes, what does the artwork intend us to think or feel, or maybe, what is the artwork asking of us, what is it inviting us to do?

Alice Lang, Feels Bad Man, 2017. Marbled paper and acrylic on paper, 19 x 24 in. Courtesy of the artist.

I am describing a critical practice, of hypothetical thinking and presumed temporary relations, which is infused with doubt and uncertainty. It is also a space of vulnerability, as we all feel vulnerable when we enter into such a precarious discourse. Authoritarian critical discourse shuts down the possibilities that this space might open up, by re-establishing an implied figure, the one who knows, and guaranteeing that our uncertainty has a limit. In my view, the limit to uncertainty is the work itself—its material form— and we engage it through discourse.

Part of what makes soft talk possible is time. If there’s plenty of time, there’s an openness that allows for uncertainty—a kind of suspension of certainty, and certainly a suspension of judgment. At CalArts, Michael Asher’s critique classes continued until there was nothing more to say. If someone wanted to revisit a thought that had come up hours before, the group continued the conversation. Through circling back, taking time, through repetition and working through, a form in language was built up, not equivalent to the artwork, but coextensive with it.

I believe that what we are committed to doing together is making an exciting, generative, productive conversation around what may be not very good artwork. This isn’t primarily driven by a wish to help the artist make better artwork, although that could be a byproduct of the conversation. We do it to make us better at looking and interpreting and responding to new ideas and new forms that may unsettle and disturb us. We do it to bring words to these forms. And it can make us better artists and viewers, because through this process we can begin to have a better understanding of how artworks operate.

As for soft talk, I like it. I like the implication that we’re maybe doing something gooey and awkward and generous, and that our discourse gives, like a pillow, rather than cuts, like a knife. And part of what I want to suggest is that there are ways to think about rigor in the soft talk that we are doing. I believe that being able to point to the precise material elements in the artwork that produce the sensation of “weirdness” (or any other response) is how we focus the conversation on the specifics of the work. I believe that our conversation has to be anchored in the materiality of the work in front of us; otherwise it can indeed veer off into unstructured reminiscences of banal feelings. But as someone deeply invested in psychoanalytic theory, I do not use the term “free association” pejoratively. Freud’s practice of “free association” is far from free, because following the chain of associations brings us to deeper meanings that we cannot access otherwise. It’s unrelenting, the way free association takes us there. So following our thoughts (while staying located in the formal and material qualities of the specific artwork) takes us places we might otherwise never go, and allows for something to be revealed.

It’s paradoxical. As artists we may work towards controlling the meanings produced by the artwork with great intensity and intention; we tighten the screws on structures of representation and materiality, trying to limit and direct the possible readings of the work. Yet it is precisely in this tightly controlled work that inadvertent affects and effects squeeze out the edges. What we didn’t intend is often a crucial part of the final work, and the more intentional we are in our practice, the more these by-products ooze out and come into being. That seems to me like a good thing.

For me, what’s exciting about artworks is the way that meanings proliferate: that unintended leakage and ooze at the level of meaning is generative and alive. New contexts make new meanings happen: a performance in a prison, or a factory, or an airport, or in a different decade literally operates differently. I see artworks as mechanisms for generating meaning. I’m thrilled by the process of following up on those meanings and pointing to the precise formal and material and contextual elements that produced them.

I am personally less interested in locating the artwork within the history of contemporary art (although that may be an important dimension of the work) than I am in understanding how the work engages the specific context of our historical moment. I am intrigued by the presumption that all worthwhile artworks are somehow engaged in a process of critiquing the dominant ideological and political formations of our time. At CalArts, that’s called “criticality,” and the cry goes up, “Where’s the criticality?” Some people believe that’s what validates an artwork, or invalidates it. I think there are many ways to challenge received ideas and power structures, and sometimes refusing to engage dominant ideology directly can be a way of carving out another space for discourse and experience. Sometimes the artwork steps aside from explicit “criticality,” in order to do something else, something other. But I am also convinced that there’s no space outside the power structures of our world, so inevitably we speak a language that participates in the oppressive ideologies of racism, capitalism, the patriarchy, even when our work proposes an elsewhere. In this context, the other thing the artwork may be doing will be temporary and precarious, and those qualities are precious and worth articulating.

There are, needless to say, multiple strategies to make the critical conversation productive and exciting. Bringing in literary and pop culture references, making connections to other artists of the past or the present, finding the underlying discursive interconnections within the work are all approaches we value and pursue. At CalArts, when I started teaching there in the early 1990s, the dominant mode of critique was to ask the artists to explain their intentions in as much detail as possible, and then to use that verbal explanation almost like evidence in a courtroom, measuring those stated intentions against the artwork itself. It was productive in that it helped the artists see how far their artworks had drifted from their conscious stated intentions. Yet that drift was seen as a problem, and artists were slammed for producing work that didn’t line up with their words. Bringing language to bear on the artwork was a way to build a case, using the artists’ own words against them. It was brutal. It also avoided the risk of hypothetical thinking, that is, the risk of entering a zone where the artist’s stated intentions are temporarily set aside.

Without the artist’s instruction or direction, we can venture into a space of uncertainty, where viewers wonder what is going on with this particular artwork and together find words to make an account of the work, slowly building a discursive form that can hold the multiple meanings the work generates. I believe that drift and divergence are not only inevitable, but also of great value, as they open up a possibility for the artist, and viewer, to find out something that’s true, that we didn’t already know. When I do a studio visit with an artist, this is my wish: to uncover, in the conversation together, something that’s true about the work, that hasn’t yet been recognized. It’s a very uncertain process, but sometimes I know when we’ve got there: a silence falls, a moment of reflection. This possibility of discovery (through the making and the discussion of the work) keeps me coming back to the critique, to this endless exchange, where we try to articulate the ways that artworks operate and generate meaning and, in weaving together these different conversations, to sustain a precarious and ever-changing community.

Leslie Dick is a writer who lives in Los Angeles. She has been teaching in the Art Program at CalArts since 1992.