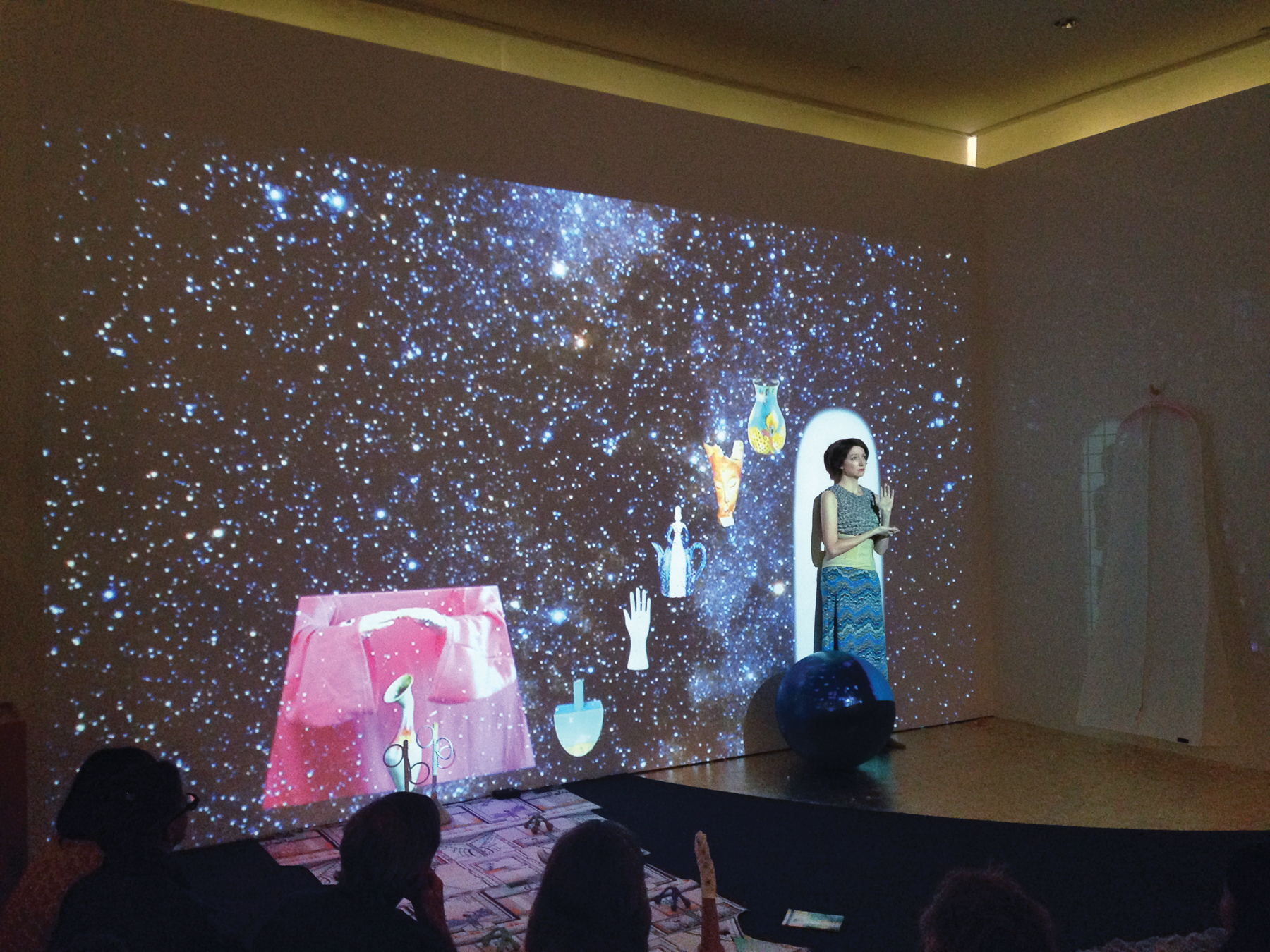

Shana Moulton, Detached Inner Eye, 2014. Exhibition and performance as a part of A Public Fiction, by Public Fiction within Made in L.A. 2014 at the Hammer Museum. Courtesy of the artist and Public Fiction. Photo: Sarah Rara.

Finally, I get to meet “Cynthia,” Shana Moulton’s video and performance alter ego for over a decade. Tonight Cynthia wears a squiggly multi-colored skirt, greyish top, her signature bob, and a strappy tan back brace. Her sidekick is a large blue exercise ball, the type that has become pervasive in yoga videos. Another ball, projected at almost the same size, appears via video, but rather than another exercise ball, we see the central blue trackball of an ergonomic mouse. Cynthia raises her prop overhead and advances to merge these forms—the real and the projected. In the process, she creates a void in the image with a massive shadow. Cue the themes of projection, mediation, and mimicry. Cynthia takes a seat on the ball as a feminine hand grasps its projected double. Fingers roll the trackball and Cynthia’s body matches the action, or perhaps vice versa. Is she a full body cursor, remotely controlled? “I have this deep pain all over my body,” says a voice. We start to feel the pain hinted at by the back brace. Cynthia’s anxious hypochondria begins to fill up the space like a fishbowl. A stream of pharmaceuticals pops up behind her: Pristiq, Boniva, Lyrica, Restasis. Googling the names after the performance, I find this list corresponds to ailments as follows: major depressive disorder, postmenopausal osteoporosis, fibromyalgia, and a personal favorite, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, or dry eye syndrome. Imagine—all that pain and you can’t even cry.

These drugs have more in common than just Cynthia. Women are their primary target audience; a few of them also share a particular advertising strategy: their logos incorporate figures, made of smooth curvy lines, soothing colors, and the suggestion of movement. Moulton has scrutinized the morphology of similar logos before, as in her 2010 visual essay for Art Fag City, “Squiggles, Trees, Ribbons and Spirals: My Collection of Women’s Health, Beauty and Support Group Logos as the Stages of Life in Semi-Particular Order,” for which she collected almost 200 logos. The collection makes clear the clichés of woman-directed signage in a long scrollable webpage.1

Moulton borrows the logos of these trademarked drugs for the video component of Detached Inner Eye, but not in their usual graphic line forms. Instead, she makes homemade costume versions, a bit pouffed and saggy, with people inside to animate them as the design of the print logos suggest but do not deliver. Within the projection that acts as a stage for Cynthia—the singular performer in the room—three figures dance together in a row in front of a television. This screen within a screen shows red curtains, as if to indicate yet another theater buried in a mise en abyme. The soundtrack is nineties new-age icon Enya, with a fast beat layered under smooth, modulated vocals and intermittent radiant bursts of synth sound. Pristiq bounces from side to side with occasional floppy kicks to the beat. Boniva’s arms, legs and head are three distinct pieces that move fairly independently, but keep time. Restasis is clearly the most impressive both in form and movement, with a slanted teardrop for a head and one arm jutting out and curling around to create an abstract eye. Also following the trancelike rhythm, Restasis rolls her shoulders while her head, arms, and hips all move almost isometrically, rippling up and down the body—a full body wave. The layering and campiness goes beyond didactics, verging on oppressive—it is visceral. Cynthia steps into the light of the projector to join the three dancers, waving her arms while the words “Lyrica” and “fibromyalgia” on a background of what I assume are fatigued nerves move over her and envelope her, pulling her into the image. Maybe there’s a kind of identification, or a kind of therapy. Yet this crisscrossing of stimuli does not align with the ailment-and-cure model, instead it allows a complex relationship between pleasure and pain to co-exist and it asserts the body as medium. Cue themes.

Shana Moulton, Detached Inner Eye, 2014. Exhibition and performance as a part of A Public Fiction, by Public Fiction within Made in L.A. 2014 at the Hammer Museum. Courtesy of the artist and Public Fiction. Photo: Sarah Rara.

Detached Inner Eye was part of Public Fiction’s project in the Hammer Museum’s Made in L.A. 2014 biennial. Founded by Lauren Mackler in 2010, Public Fiction is a noncommercial art space generating exhibitions, publications, and event programming with a significant collaborative effort. Mackler co-curated, with Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, Public Fiction’s contribution to Made in L.A. Public Fiction programmed an “Episode” and a “Chapter” staged in “The Room” for each of six sections, as well as a correlating piece at Public Fiction’s space in Highland Park, know as the “Set.”2 Some stock objects were in The Room for the duration of Public Fiction’s project: a chair, desk, potted plant, and various floor and wall treatments. To this group of props, Moulton has added her own objects, many of which are fashion supports: stacked busts for necklace display, a sculpture made of a lamp with two partial heads fitted with hooped earrings, glove molds, and two garment bags. The current Chapter, by Chris Kraus, is available on the desk just outside the entrance to The Room. The pairing was chosen by Public Fiction, perhaps because the artists share a semiautobiographical approach.3 Kraus’s short text revolves around “Suzanne,” who is more than once described as seeming “healthy” and is an excellent corollary to Moulton’s Cynthia, whose journey operates as an awkward accumulation of interactions with products that offer small snippets of narrative, which she assumes as her own. Kraus writes: “Actually, I was thinking the other day that it was like the surrealist experiment with the exquisite corpse. You start with part of an image and create your own addition to it, and end up with something you’ve created, but it doesn’t quite fit. Because subsequently I heard some stories about her. And it was as if each person had added their own little piece, without knowing what came before.”4

The synchronistic script is offered on the threshold to The Room and confirms Moulton’s terrain as a myriad of fragments, doppelgangers, and digitally baroque space consisting of labyrinthine portals and interstitial spaces. We are embarking on a voyage through narrow pathways opening into crevasses and pools filled with muddy meaning. The work asks us to suspend the impulse for direct analysis and float in a field that vacillates between cohesion and dispersion. But we also follow the anxieties and desires of Cynthia’s personality in a cut-up style, akin to those of Suzanne in Kraus’s text. Moulton’s title Detached Inner Eye is playful, if darkly. In the video’s appropriated snippets of pharmaceutical ads, medical renderings show the interior of the body from the perspective of a camera. This type of “detached eye” invades and surveys our innards. The medical use of the term “screening” emerges as a pun that again binds the body-image-screen relationship, like Cynthia’s initial gesture connecting two blue orbs that are like drowned worlds, like eyes.

Shana Moulton, Detached Inner Eye, 2014. Exhibition and performance as a part of A Public Fiction, by Public Fiction within Made in L.A. 2014 at the Hammer Museum. Courtesy of the artist and Public Fiction. Photo: Sarah Rara.

The eye has often been a stand-in for the body. Occulocentrism here, however, reminds us of all that is not captured by the eye. The audience surrounds Cynthia to consider how her subject might form before so many speculative pressures, both interior and exterior. She pulls us into a single point, moving outside-in and inside-out, the scientific, locatable, micro, and technical up against the un-locatable, ephemeral, macro, and transcendent, all within a relentless flow of mundane cultural references. There is an unrelenting quality to this work; between Cynthia’s earnest faces and peaking eyebrows, a frenetic and overfull visual landscape, and the more sophisticated pared down visual language of the ads she pilfers, there is little room to be objective. The joining of overstimulation with the dumbness of the information is uncomfortable. It makes us feel like bodies too. Yet Moulton’s work doesn’t hit us over the head with the long and weighty history of the bodied being—it glides along many possible references and configurations from Descartes’s cogito, Lacan’s mirror stage, and Deleuze and Guattari’s body without organs to Hayles’s notion of the posthuman. The garment bags hanging in the room suggest the possibility of trying them on, without obligation. Mid-way through the performance, corporeal Cynthia climbs inside a garment bag, which all at once becomes cocoon, second skin, body bag, and portal.

Shana Moulton, Detached Inner Eye, 2014. Exhibition and performance as a part of

A Public Fiction, by Public Fiction within Made in L.A. 2014 at the Hammer Museum. Courtesy of the artist and Public Fiction. Photo: Sarah Rara.

The “inner” of Moulton’s territory branches toward emotional and metaphysical quests. A litany of self-help and consciousness-expanding soundtracks and objects appear throughout the piece, starting with the exercise ball and extending from Pink Floyd, Jill Bolte Taylor finding nirvana during a stroke, and the “picture puzzle pattern door” from a DMT trip to face masks, Kleenex, self-massagers, goddess sculptures, and a back scratcher. Cynthia’s power as a cursor is honed as she ascends mountains and treks through forests using floating “wellness” products as nodes to propel her though an expanse that is a cross between a videogame, guided meditation, and an elevated shopping experience. Arriving at the next level, her background becomes the cosmos. Corporeal Cynthia leans against the wall, bathed in a framing light from the projection as she mirrors the gestures of a magician’s hands extended from a red robe. Finally, Cynthia herself is doubled—her visage appears on a scenic mountaintop. Roles and motives pivot; insecure-bodied Cynthia retreats by zipping herself up inside one of the garment bags. Projection Cynthia dons a blue robe, lies down, and seems to astral project to dance in a psychedelic frenzy. The floodgates open to an infinite multiplicity of Cynthias. A seeker’s journey, punctuated by dance.

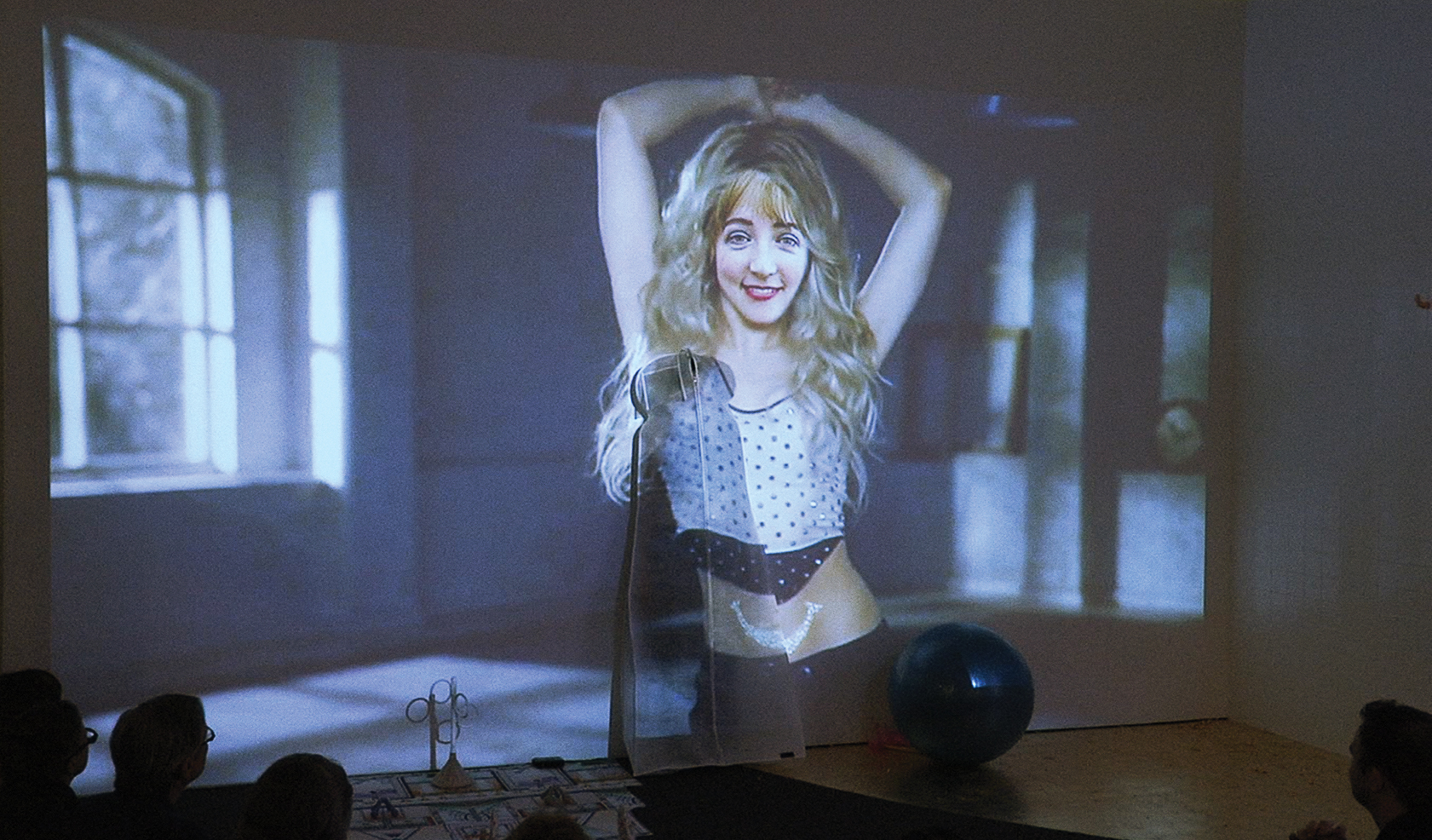

While physical Cynthia rests in her chrysalis, screen Cynthia finds her way to a cabin with a large wooden goddess incorporated into its façade. The framing shifts so the goddess covers Cynthia in her sack. Two green-screened human arms overlay the goddess’ and begin to undulate in exact symmetry. Zoom out and our fearless heroine wanders inside the cabin and finds an Activia probiotic yogurt! One taste and she is possessed. Seemingly awakened, she returns to the forest, takes a moment to mimic the posture of the goddess, and a zip of light encircles her, peaking in a bright flash above her head. This flash of light turns to a glittery stream of fairy dust that leads us into an actual Activia commercial. The ad features a whole colony of Shakiras in the forest, awoken individually by the computer-guided glitter. Raising arms overhead, in the now familiar goddess pose, and softly gyrating hips below, the relay of Shakiras all dance to the singer’s 2014 pumping hit Dare (La La La). The roving glitter reaches its target, Shakira’s tummy (their word), where it lands and distorts into a faceless smile. “Feeling good starts from within.” At the finale of the ad, Cynthia’s face replaces Shakira’s, and the transformation is complete. Much like a corset with all its straps and its “nude” tone, the back brace approximates what Cynthia’s waist might look like if it were bare midriff like Shakira’s.

Shana Moulton, Detached Inner Eye, 2014. Exhibition and performance as a part of A Public Fiction, by Public Fiction within Made in L.A. 2014 at the Hammer Museum. Courtesy of the Hammer Museum.

At this point in the performance, real-time Cynthia breaks free of her chrysalis and tosses aside the back brace. Behind her is a waterfall of images: goddesses, dolphins, seahorses, bejeweled facades with disembodied dancing limbs, fractal spirals, women’s health pamphlets, a suite of vessels in a kaleidoscopic border around a box of Kleenex, cats, hands. She dances again and wields something similar to a rhythmic gymnast’s ribbon, but with a more substantial fabric. Her role is now conductor, her cursor has become a wand that can express even greater movement. Again, Cynthia casts a shadow on the projection; this time she is quite close to the wall, her shadow practically matches her body. Within the shadow, a single oval of light shines from a handheld device. In the first scan, we see the skeletal structure; moving back down, the organs; on the third pass the strong color and light of the chakras; and finally a radiating, multi-colored astral being. Everything shifts. Cynthia is the master of her image world. What at the beginning of the piece felt like remote control, then gave way to possession, has arrived at undeniable agency.

Shana Moulton, Detached Inner Eye, 2014. Exhibition and performance as a part of A Public Fiction, by Public Fiction within Made in L.A. 2014 at the Hammer Museum. Courtesy of the artist and Public Fiction. Photo: Sarah Rara.

Cynthia’s specificity counteracts the simplicity of the clichéd logos and products that are visually dominant in Detatched Inner Eye. But equally, Cynthia is a projection space, a vessel generated through market research, a Californian style of health and beauty. It is Moulton’s deployment of dance that ultimately resists the flattening out of experience that seems like the forgone conclusion of her appropriated advertisements. The dancing—when actually happening—manages to make space, where suggestive lines on the page prove to be static. Vacillating along the spectrum of pleasure and pain—cohesion and dispersion—the dance offers a complexity of embodiment. Despite all the drugs it took to get here, the piece manages to avoid being prescriptive; it welcomes laughing, crying, and dancing as appropriate responses. Finally, our Restasis lady of tears is projected again, in front of a rainbow; she bows, and it is the end.

But the true transformation is of Cynthia back to Moulton. I’ve been waiting for this unveiling. She removes the wig and thanks us for coming. I think I could cry.

Brica Wilcox is an artist based in Los Angeles. Raised in Arizona primarily by her mother, who continually strove for higher consciousness, she was named by her parents’ metaphysical teacher. He came up with her name in a trance. It is pronounced Brē’ka. She is a member of the X-TRA editorial board.