Once expanded cinema split, flipped, and warped the screen in the 1960s, filmmaking’s old guard found themselves like clowns on an ice rink. Nothing had been more reliable than the stationary, flat, and singular projection surface. It had been a fixed window onto a contained world governed by shots and cuts. Now the screen was whirling around and folding over itself, cavorting with ceilings, bodies, and other untraditional surfaces, and producing hybrids with fruit-fly speed. There was no chance of pinning it down, flattening it out, and sewing it back together again. But what if the pesky devil could be figuratively captured instead? What if the expanded screen’s mitosis and mutation could be halted and then trapped in an imaginary plane—like when General Zod and his minions were banished to the Phantom Zone in Superman II (1980)? Or like in the funky martial arts film that Shambhavi Kaul sources in her Fallen Objects (2015), which stars a flying pair of shears that valiantly attempts to subdue an endlessly replicating black, screen-like void.

When I first saw Kaul’s work, at Jhaveri Contemporary in Mumbai in November 2014, I arrived with my head filled with space—specifically Indian space. A few days prior I had watched Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014) at Sterling Cinema, around the corner from Mumbai’s Victoria Terminus. If you’ve seen this movie, you probably remember its nods to When Worlds Collide (1951) (Earth is doomed and humans need a new home) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) (outer space is inner consciousness). But, just a few minutes into the film, well before the sublime themes and the big budget spectacles began to materialize, the Mumbaikars sitting around me were already aroused. Hero Matthew McConaughey was driving his pickup, with son and daughter beside him, kicking up clouds of dust and mowing down corn fields in pursuit of an errant aircraft. “It’s an Indian Air Force drone,” Dad says with a twang, “Its solar panels can power an entire farm.” No fewer than a dozen Sterling patrons cooed, “Ohhh,” the second h rising in amazement and third firming up with national pride.

Science fantasy was in the air. In September 2014, with the Mars Orbiter Mission, the Indian Space Research Organisation had succeeded in putting a space probe into orbit around the Red Planet, inspiring higher-ups to promise manned missions to follow. Meanwhile, rightwing crackpots were claiming (once again) that ancient Hindus had mastered flight millennia ago in the form of the mythological soaring palaces known as Vimana. That summer, Farouk Virani had released Vimana, a short Hindi film about two Indian astronauts on a one-way deep space voyage. The entire October 2015 issue of Studies in South Asian Film and Media was dedicated to the topic of Indian science fiction. Researchers at Jadavpur University were unearthing Martians and land-before-time beasts in old Bengali newspaper comic strips through the archival The Comic Book Project. Artist Sahej Rahal would soon begin roaming the state of Maharashtra in the guise of a Jedi knight, resulting in the exhibition Adversary at Chatterjee & Lal in Mumbai in early 2016.1 Half of the second Kochi-Muziris Biennale (2014–15) was focused on the cosmos. And, for no rationally explainable reason, I began staring at Baburao Sadwelkar’s paintings online, mesmerized by his floating palaces and extraterrestrial landscapes. A few months later, I was at the security gate of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in the Navy Nagar area of Mumbai, asking to see the art collection built by nuclear physicist Homi J. Bhabha for India’s leading science research center. Standing in the institute’s halls, abstract paintings by V. S. Gaitonde and Krishna Reddy no longer looked to me like statements about facture and color, or mythology and inner consciousness. They were optical trips to worlds not within but way out, amongst the stars. Something was up.2

Kaul claims that she did not enter India in the latter half of 2014. She was in North Carolina, where she lives, and did not make it to her own show. Presence, however, is a relative thing. It is well understood (and I am not talking about modern telecommunications) that psychic connectivity is not dependent on physical proximity. Granted, Kaul had been making work inspired by supernatural atavisms, extraterrestrial landscapes, and filmset magic for many years. But that alone cannot explain the unsettling fact that her show at Jhaveri opened on November 12, just a few days after Interstellar’s Indian release on November 7. And get this: Her show was titled Lunar State. From what I recall, there were no eerie, 2001: A Space Odyssey-style monoliths in the show. There didn’t need to be because, effectively, the whole show was a monolith. Lunar State was a veritable beacon planted on the moon (Jhaveri Contemporary is a remote satellite of the Mumbai art world’s center, which is located in Colaba, some miles away), sending out secret signals for millions of seconds prior to the show’s opening to ensure that the right human transponder would arrive. Wily Kaul, exploiting the ignorance of her gallerist and the press, surrounded the show with turgid academese about post-colonialism, non-places, and mediatized identity. But my brain, having been pre-tuned by Christopher Nolan, was synced to the artist’s vibe. I perceived the constellation of signs through the artspeak noise.

UFO conspiracy pervaded the show. The five-minute Scene 32 (2009) turns the desiccated salt marsh of the Rann of Kutch into an Indian version of Area 51, with mysterious tire tracks implying dangerous “aliens” over the border and secretive tests in nearby deserts. There was also the newer Night Noon (2014), a film shot in California’s Sonoran Desert. The film pays subtle homage to the simulacra overlaying this otherwise blank landscape, where many a Hollywood spectacle—from space adventures to Egyptian epics and modern wars—has been filmed. We see hardpan hills, dunes, and an inland sea. The wind whistles ever more sharply. We see a dog and a parrot up close and tight in the camera’s frame, though never their master, who one assumes must be a Robinson Crusoe type, stranded with only animal companions. Eventually the sun sets on this day-in-a-life on a foreign planet. As the sounds become electronic and strange, a bright light appears in the air, like in a 1950s-style Martian invasion.3

Shambhavi Kaul, Scene 32, 2009. Video still. 16mm converted to HD video, 5 min. Courtesy of the artist and Jhaveri Contemporary.

Kaul understands that there is no such thing as a truly alien world for people raised on movies and television. She has spoken about how screen landscapes provide a sense of home that is at once uncanny and familiar, even when those landscapes are ersatz, exotic, and geographically unidentifiable.4 This paradoxical nostalgia certainly speaks to me. Though I grew up thousands of miles from any desert and have never been to Lake Powell, in Utah, or Tunisia, I regard the Planet of the Apes and Star War’s Tatooine home. Kaul’s movies also take me back to evenings spent stoned in the glow of the Essential Cinema program at Anthology Film Archives in Manhattan—not to hardcore structuralist filmmaking or the “personal film” genre, but rather to the quaint magic that prances out from Georges Méliès, across Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), and into Joseph Cornell’s films. Which is to say, while Kaul is a first-class cine-dork, she is also an upstanding modernist (“I absolutely ADORE Vertov,” she gushed to me in response to a fact-checking email, letting her professorial guard down) and is careful to stay this side of artistic respectability by avoiding what fandom usually opts for, which is spoof.

On that note, Kaul’s work reminds of a stupid movie that I used to love: Hardware Wars (1978), Ernie Fosselius’s famous send-up of the original Star Wars. That Fosselius has cast a clothes iron as the Millennium Falcon and a vacuum cleaner as R2D2 (an echo of the flying objects in a number of Kaul’s films) is not the only reason I say this. And it is purely coincidence that the Han Solo character (Ham Salad) looks like an ugly version of Indian film star Amitabh Bachchan. The key to much of Kaul’s work, aside from her ability to tap into mediatized nostalgia, is her sense of humor. More and more, her work has come to be defined by what we might call modernist screwballism: Hardware Wars without the humans. While pursuing an orthodox modernist antipathy toward narrative and, particularly, the human figure, she simultaneously indulges in a personal penchant for zany source material, with magic often serving as a conjunction between the two and a way to tastefully structure her comedy.

One of her first works in this comic magic mode, Mount Song (2014), draws on Hong Kong martial arts films from the 1970s and 1980s. The source material isn’t science fiction by any definition. Instead, Kaul has chosen (as in the later work Fallen Objects) movies that feature sorcery and the supernatural. Magic and fantasy—rather than utopia, technological futurism, or speculative fiction—were likewise what she accentuated in sci-fi works like Scene 32 and Night Noon. Her way of editing further emphasizes those tropes. She removes all scenes with humans, leaving but remnants of the story. As a result, the special effects, sets, and props appear as autonomous and self-animating phenomena. Doors open, clouds expand, trees shudder, buildings explode, glowing birds fall—as if they are themselves statements rather than contexts or conjunctions. She makes the hocus-pocus of chintzy special effects seem philosophical by chiseling around them with tight cuts and aggrandizing them through loops.

Shambhavi Kaul, Mount Song, 2013. Video still. HD video, 8 min. Courtesy of the artist and Jhaveri Contemporary.

“One could say that my work is not attempting a critique, or a subversion, as much as it hopefully creates a field for criticality,” said Kaul, “a chance to look at these images again, to think about what they conjure up and what complex ideas they retain.”5 Very well. But these entities she calls images are also things in themselves. They are not passive. They do not wait to be interpreted. Their animation strikes before the viewer has time to think about their cultural discourse or their relationship to memory. Kaul has spoken of landscapes as actors. Works like 21 Chitrakoot (2012) and Mount Song are for me like Stuart Rosenberg’s The Amityville Horror (1979), where the human actors are intimidated not by ghosts or goblins but by architecture. In Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982), the television, the closets, the backyard pool, the backyard tree, and ultimately the entire home attempt literally to devour the happy family. “It doesn’t want people,” says the old lady about the old house in Peter Medak’s The Changeling (1980). Kaul has compacted that aesthetic further, to the point where the moving image assumes the shape of a visual and conceptual architecture that not only moves on its own accord but also, through that animation, physically drives out humans and their stories. There are many haunted house movies. Kaul instead creates movie haunted houses.

And they’re funny. In the way they are funny, they remind me of Japanese artist Tanaka Kōki’s early work, circa 2005. On video, Tanaka performed simple tricks—like tossing a fat rubber ball into a metal bucket and having that trigger a simplified Rube Goldberg chain reaction, or throwing a boot through a second story window and having it land directly onto a drum. These feats presumably took many tries to execute successfully, but as neither the outtakes nor the human agents are shown, the execution looks wonderfully and absurdly smooth. It is as if objects are capable of a higher level of dexterity when left to their own devices, without the muddling intervention of clumsy humans. It’s like the silly home video showing the ten-year-old kicking the ball a hundred meters miraculously against his grandmother’s head, or that serendipitous bounce that momentarily makes the drunk golfer a world-class talent. By hiding the outtakes and tightly controlling his scenarios, Tanaka is able to reproduce this humor of stupendously dumb luck.

Shambhavi Kaul, Night Noon, 2014. 16mm converted to HD video, 12 min. Courtesy of the artist and Jhaveri Contemporary.

Jackie Chan was, before he moved to Hollywood, a master of this technique on a far more elaborate scale: repeat an impossible stunt on film endless times until it comes off perfectly, making the human look like an acrobatic genius—or, more exactly, like too much of an acrobatic genius. As all bad liars learn, excess signifies artifice, something that Chan always acknowledged at the end of his films by running the outtakes beneath the closing credits. Slapstick provides some of the comedy in his films. But a deeper laughter stems from the constructed nature of his miracles. How we respond to a trick partly depends on how the tricksters do their hiding, whether they keep from us the truth of the matter or whether they take us into their confidence. Professional magicians reveal their trade only to inner disciples. Comic magicians, on the other hand, compress the hiding and the revealing, juxtaposing one against the other in a limited time frame. Laughter is a privilege. It is the expression of pleasure gained from being allowed to see the inner workings of a trick while still enjoying the experience of its outer effects.

Kaul works in reverse from Tanaka and Chan: She takes completed films and judges the entirety of the story and all human action as outtakes. Yet the resulting humor is similar. The self-animated sets not only act ridiculously, they look put-on. And while they thus may not be convincing, they are nonetheless impressive. Her editing is simple and straightforward, but that is precisely why it is effective. What makes Kaul’s movies comical at a deeper level is this balance between deft technique and open artifice. If she engaged only in the latter, she would be making spoofs. But she is careful to maintain that look of magic, in which the genre codes are still functioning even while they are being laid bare. She avoids camp. As she says, these are settings we believe in even though we know they are fake. We inhabit them mentally and emotionally even though we know they exist nowhere physically and are rife with stereotypes. A viewer can approach this matter coolly, and reflect on our personal identification with “mediatized non-places,” as Kaul and many critics have done. But that tone misses the humor. It misses how that process of identification is structured by Kaul as a comic magic show in which performance and artifice are played off each other.

Kaul’s landscapes are indeed familiar. But it is important to note that most of them are familiar to us specifically from childhood. While watching her movies, we are looking upon not so much the kitsch of popular entertainment as upon the sweet and exciting naiveté of our own pasts. Because Kaul constructs her works like movies—that is, by employing montage and a modicum of narrative development—watching them inevitably rubs against conventional experiences of cinematic viewing. One sits down in a darkened room and looks at a screen (nothing special here), but her focus on studio sets and short shots transforms the viewer’s relationship to cinematic space and fantasy in curious ways. With the actors gone, relations of scale between the viewer’s own space and the diegetic space of the source material evaporate. With the sets accentuated, the internal world of the film becomes shallow and sometimes flat. The overall effect is like that in tilt-shift photography, in which the focal details turn toy-like and the architecture and the landscape around them condense into a miniature diorama. What were elaborate fantasies in the source material become vulnerably small in appropriation.

Shambhavi Kaul, 21 Chitrakoot, 2012. Video still. Found footage, color, sound, 9 min. Courtesy of the artist and Jhaveri Contemporary.

Cinema becomes a magical nursery room. Watching Mount Song is like seeing the toys coming alive at night, after the children go to bed. Again, the effect depends on being simultaneously enchanted and privy. We have one eye open, faking sleep but actually alert. The toys know they are being watched. In fact, it is for us that they are dancing. But they do not let on that they know. If they did, the magic would be destroyed. We will be voyeurs and they will be exhibitionists, but heaven forbid our eyes meet, for then the tension would be lost, and the performance would lapse into either storybook whimsy or adult camp. As the kid who loves Disney and Hollywood also thinks that the backyard or neighborhood garden is forest and jungle enough for an afternoon adventure, so a family road trip to the Californian desert is all Kaul needs to get to outer space. It is all mediatized viewers of her work really need, even in a setting as decidedly non-futuristic as twenty-first-century Mumbai.

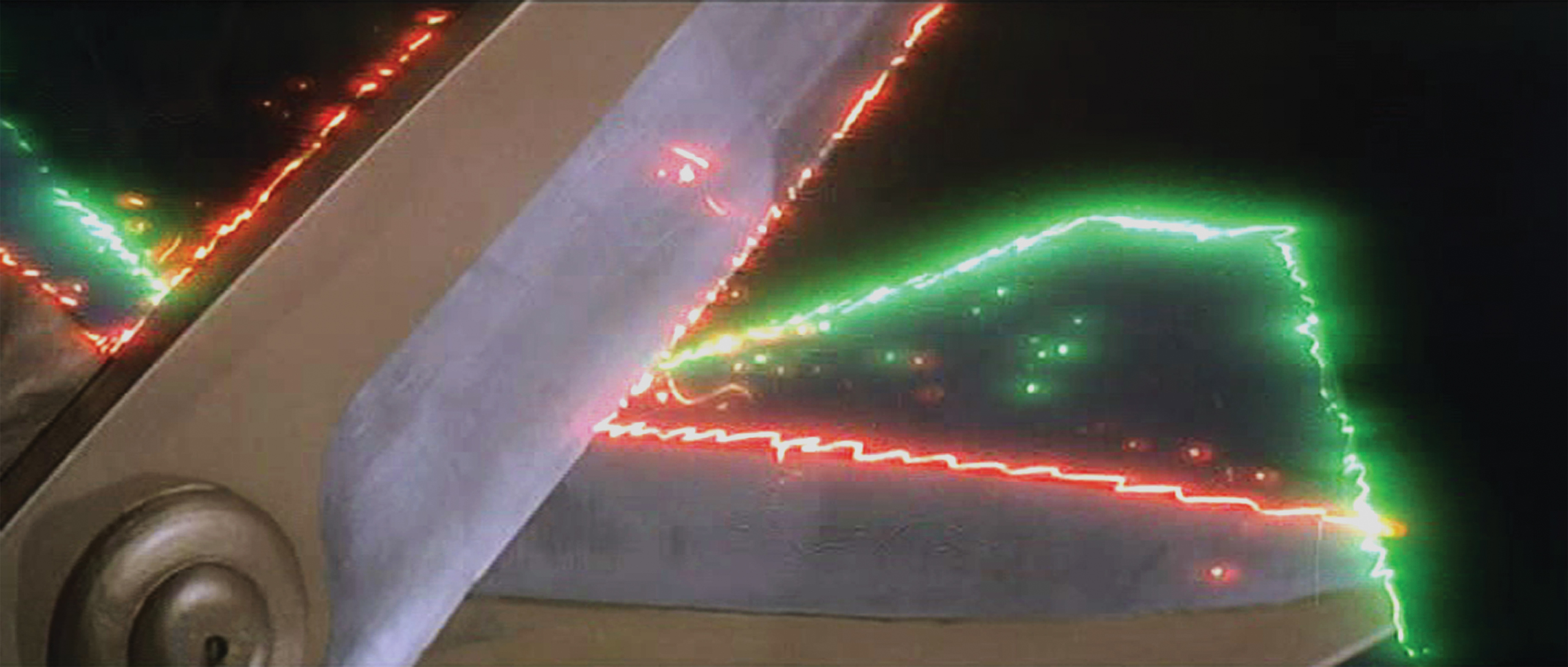

This brings me to Kaul’s newest works. Relative to her oeuvre, the editing in Fallen Objects, first shown in 2015, is simple. Totally silent, it is composed of seven shots from an unnamed Hong Kong martial art film, showing magical flying scissors (limned in electric red) battling a black void that its around like a ying carpet (limned in electric green). The scissors and the void collide, sending off an electric crackle. The scissors split through the void, dividing it in half. The two pieces fall to the ground, and then the action picks up again, with a slightly modified rearrangement of the same shots as before. We never see more than one carpet void in the air, but the looping repetition makes one think that, somewhere, in an imaginary dimension, the carpet is being split many times over. Sure enough, placed before the screen on the floor of the gallery are six black fabric cutouts, each representing the void in different crooked states of flying and bending.

Shambhavi Kaul, Fallen Objects, 2015. Video still. HD video looped and velour cutouts, 40 min. Courtesy of the artist and Jhaveri Contemporary.

Interpreting both the sculptural objects and the flying void within the video as surrogates of the projection screen doesn’t seem far-fetched. After conceiving Fallen Objects, Kaul created her first multi-channel installation, Modes of Faltering (2016). Exhibited at the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, Tennessee (April 2016), it was comprised of six contiguous screens, each featuring a short, looped clip showing actions of rocking, turning, stroking, and panicking (various “modes of faltering”), all appropriated from mainstream Indian movies. The movements alone are creepy enough. Add to them a cacophony of creaks, thunder crashes, eerie string instruments, and birds flapping madly like bats out of a belfry and you have Kaul’s most complete movie haunted house to date.

Shambhavi Kaul, Modes of Faltering, 2016. Video still. 6-channel HD video, looped. Installation view, UT Downtown Gallery, April 1–2, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Jhaveri Contemporary. Photo: Mike C. Berry.

Fallen Objects is a multi-screen installation, too, but only figuratively speaking, with the additional screens either objectified as sculptural surrogates or framed within the diegesis of a single-screen projection. Kaul employs two modes of self-referentiality here: fictional capture (a screen within a screen) and comic abjection (screens cast out into the gallery). While multi-screen projections often aim for immersive spectacle, Kaul’s version invites a distanced and conceptual view. Since the cutouts are arranged in rows directly before the screen, where a theater’s seats would be, you would be forgiven for thinking they are magic carpets to sit on and ride away into cinematic reverie. But one does not sit on a screen. Looking at these fallen surfaces, one sees only a cinematic dead zone. Though superficially “animated” by quirky contours, as substrates for projection they are dead. They are not even ambient. Made of black synthetic velour designed to absorb light, they are black holes from which the projected image can never escape. If the traditional white screen is a window, the black screen is a prison.

Shambhavi Kaul, Fallen Objects, 2015. Video still. HD video looped and velour cutouts, 40 min. Installation view, Sunaparanta Art Centre, October 4–22, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Jhaveri Contemporary.

Near the beginning of Disney’s Peter Pan (1953), the cocky punk from Neverland appears on the Darling family’s roof in silhouette. He is there because he wants his shadow back. According to J. M. Barrie’s original text, the previous night Peter was caught snooping around inside the Darling’s rooms after listening to Mrs. Darling’s bedtime stories. Mum screamed. The family dog sprang. Nimble Peter managed to leap free through the window. His shadow, however, lingering one step behind, was cut from its owner by the closing panes. The next night, once the lights go out, Peter steals back into the nursery. With the help of Tinker Bell—like Kaul’s scissors, a luminous gold fairy who glows red when angry— Peter locates his shadow locked inside a dresser drawer. Once he opens the drawer, his shadow slips out. Around and around Wendy’s room he chases it, overturning furniture before wrestling it under control. Haplessly, he tries to reattach it by rubbing his soles with soap. Wendy, the Darling’s eldest daughter, awakens to witness Peter’s stupidity, and offers to sew his shadow to his feet. This works. Peter is whole again. With promises of more storytelling from Wendy, he takes her and her siblings to Neverland, where life is a fairy tale and children never grow up.

Kaul too believes in Pan. But while Wendy keeps the window open at night with the hope that Pan might visit, Kaul keeps it tightly shut, torturing Pan, forcing him to flit around anxiously outside in the black box of night, while his shadow lies inert inside the nursery of the white cube.

But expanded cinema finds a way. As long as the white cube exists, the split screen will continue to subdivide and multiply. The artist tells me that, for the most recent showing of Fallen Objects at Sunaparanta, Goa Centre for the Arts, in October 2016, the work was held up in customs precipitously close to the opening. In haste, Kaul created a second set of textile cutouts and shipped them to Goa. Meanwhile, the first set arrived, just in the nick of time. The second set followed. Thus, Fallen Objects succeeded in duping its creator into producing a clone. Who would have guessed? The true identity of the magical scissors was the Department of Excise and Customs!

Ryan Holmberg is an Academic Associate of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Culture. As a freelance art historian and critic, he is a frequent contributor to The Comics Journal, Artforum International, and Art in America. As an editor and translator of manga, he has worked with Breakdown Press, Drawn & Quarterly, Retrofit Comics, PictureBox Inc, and New York Review Comics. He is also the author of Garo Manga: The First Decade, 1964–1973 (Center for Book Arts, 2010) and No Nukes for Dinner: How One Japanese Cartoonist and His Country Learned to Distrust the Atom (forthcoming). This essay was written with the support of a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Art, Art History & Visual Studies Department at Duke University.