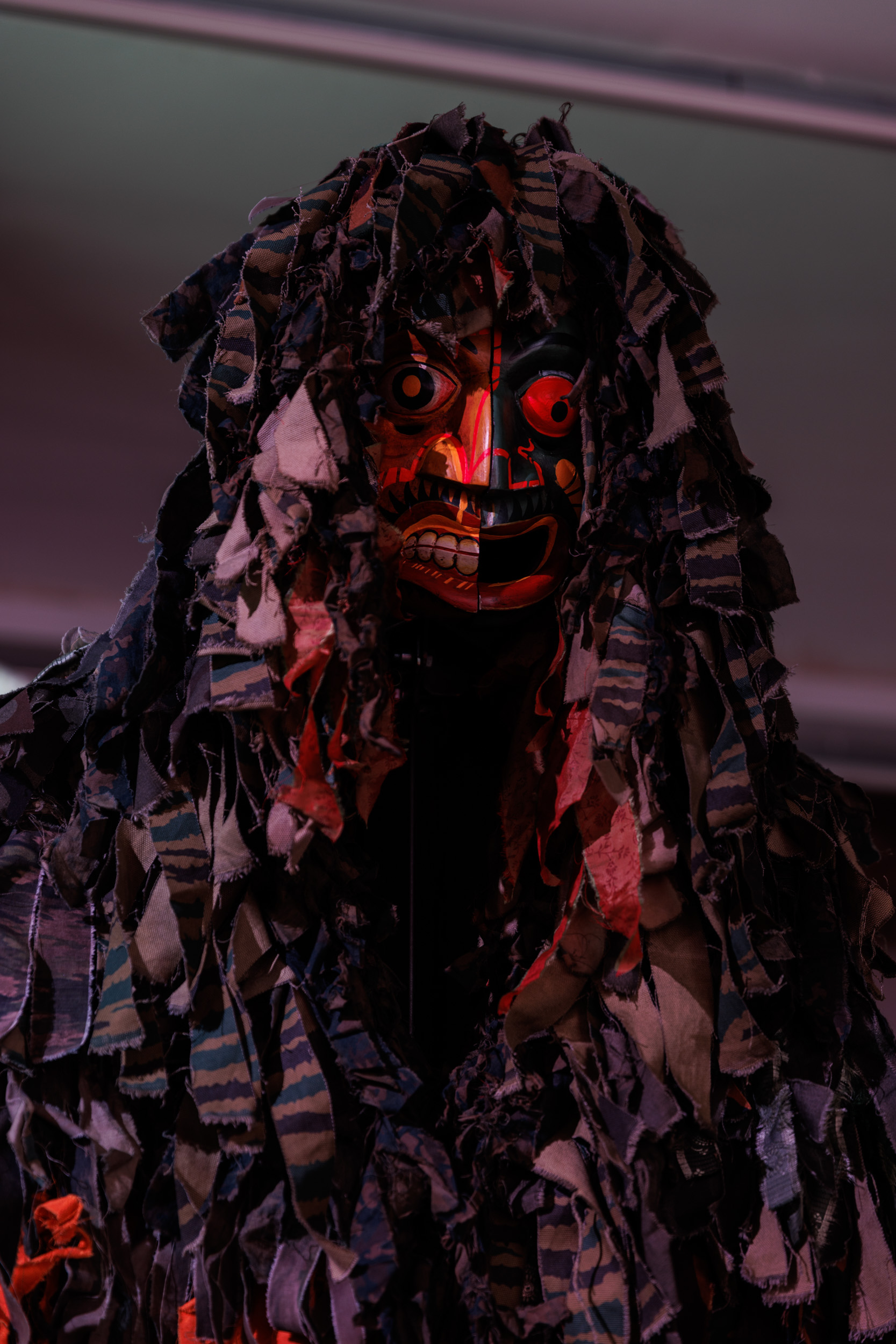

Christopher Kulendran Thomas in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, The Finesse, 2022. Installation view, Christopher Kulendran Thomas: Another World, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, October 22, 2022–January 15, 2023. Photo: Frank Sperling.

The task of writing a history of the vanquished is time-honored and exacting, and it is of cumbersome proportions. Christopher Kulendran Thomas’s Another World, developed with long-time collaborator Annika Kuhlmann, undertakes this ambitious endeavor. In the near-identical exhibitions, which opened concurrently in Berlin and London, Kulendran Thomas discloses his motive in a compellingly earnest epigraph to the curatorial text: “How do you tell the story of the losing side of a conflict when history has already been written by the winners?”

At stake is a historicization of the quest of the Sri Lankan Tamil people for autonomy and self-determination. The most widely recognized face of the struggle was the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a militant organization that fought against the Sinhalese-majoritarian Sri Lankan state from 1983 to 2009. The war ended with the fall of LTTE leader Velupillai Prabhakaran, along with the genocidal massacre of tens of thousands of Tamil civilians in the No-Fire Zone of Mullivaikkal.1 The date—May 18th, 2009—is commemorated as Tamil Genocide Remembrance Day in places where Tamil people are allowed the freedom to do so. In the island country of Sri Lanka, there are hardly any indicators of a reckoning with either past atrocity or continuing subjugation.

Kulendran Thomas’s epigraph echoes German Jewish philosopher and essayist Walter Benjamin’s prescriptions in Theses on the Philosophy of History. In Benjamin’s essay, the historian in the tradition of the oppressed must “grasp the true image of the past as it flits by,” knowing that “even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he is victorious.”2 Writing history in this register is not historical reportage. It cannot be the litany of calendar dates and casualty numbers or the triumphal tellings that flood official curricula. Rather, the past is to be retraced through the injustices of the historian’s present. Here, the historian is not only the trained professional but also, potentially, the writer or artist who commits to some narrative mode that remains steadfast to its disappeared subject until it alights on the flickers of a faint composition, extending from latter-day dissent to its distant progenitors, from the particular to the everywhere. In art and literature, this may be called a realism—or not.

The twin components of Another World are the physically impressive video installations Being Human (2019) and The Finesse (2022), which form two parts of an ongoing trilogy. Each contains a central video projection surrounded by a suite of sculptures, paintings, and/or drawings. These objects belong in the diegetic spatial setting of each video: a deracinated contemporary art white cube space in the first, and the forests of Tamil Eelam in the second. The effect is one of visual, aural, and spatial immersion, with the implication being that the viewer is imbricated, even complicit, in the vexing relations portrayed on-screen.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, Being Human, 2022. Installation view, Ground Zero, Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin, September 11–December 15, 2019. Photo: Andrea Rosetti.

Both videos assemble several personas, featuring varying degrees and forms of artifice, whose dialogues and monologues form the chorus around each work’s central themes. In Being Human, these are delivered by deepfakes of pop star Taylor Swift and artist Oscar Murillo, alongside documentary interviews with Tamil Sri Lankan artist Ilavenil Vasuky Jayapalan and Kulendran Thomas’s unnamed uncle, who founded the Centre for Human Rights in Tamil Eelam. The video sets up a parallel between the “theoretical equality” of aesthetic proposals within contemporary art and the equality of individuals within human rights discourse, with both serving to obscure existing power relations. The convergence of these two is exemplified by Sri Lanka’s Colombo Biennial, the first edition of which took place in 2009—the same year in which the war against the Tamil people was concluded. In the video, the biennial is characterized as a state-building project serving to consolidate the cultural hegemony of Sinhalese Sri Lankan rule.

Elsewhere in the video, Taylor Swift ventriloquizes on behalf of the artists about the fractured American public sphere to which her fans belong. She also purveys meta-commentary, doubling as manifesto, against the present-day imperative to authenticity, the often infeasible demand to live one’s truth. Setting up several of the problematics also taken up by the later video and accompanying artistic works, the characters in Being Human critique the sovereignty and surveilled boundedness of the categories of the human, the nation-state, and the discipline of art. That everything is a network and not a castle in a moat is a decent thesis, but instead of delivering productive discordance and agonism, the talking heads too often and too systematically leap from minute recollections of post-civil war development to galaxy-brained proclamations about Kantian idealism and hackneyed anthropocentrism. The viewer sometimes has the sense that characters have followed the grandiloquent script a bit too closely.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, The Finesse, 2022. Installation view, Christopher Kulendran Thomas: Another World, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, October 22, 2022–January 15, 2023. Photo: Frank Sperling.

In Being Human, the video is accompanied by two types of artworks. The first consists of large-scale abstract paintings that reproduce PNGs generated by training an algorithm on noted works from the Western canon and contemporary visual art from Sri Lanka. The “paint-by-number” works, which were made by hand in the artists’ studio, have a deliberate stodginess that numbs the faculties, effectively lampooning the source material that the neural networks were run through. The other set consists of folded ceramic ribbon sculptures attributed to Aṇaṅkuperuntinaivarkal Inkaaleneraam, the moniker given to a collective entity founded by Kulendran Thomas and dedicated to the legacy and future of Eelam art. Similarly, The Finesse features tall humanoid figures in masks and camouflage suits, as well as axonometric drawings of communal architectural proposals inspired by the Soviet Disurbanist school, which are attributed to one of the video’s Tamil protagonists. With the exception of the large paintings, the artworks serve to populate the gaping lacunae of the destroyed Tamil archives in excess of what would have been possible by merely foraging under the wreckage. Here, one may speak of what Saidiya Hartman, scholar of African American literature and cultural history, has influentially termed critical fabulation, in reference to her own literary techniques of weaving speculative narrative within the absences of the archives of the transatlantic slave trade, while also practicing great restraint in approaching the lives of the enslaved and refusing to “give voice.”3 As far as the authorial register and formal logic of the drawings and sculptures in Another World are concerned, it is not evident that Kulendran Thomas and Kuhlmann are similarly circumspect about whose voice becomes a stand-in for whose and to what end.

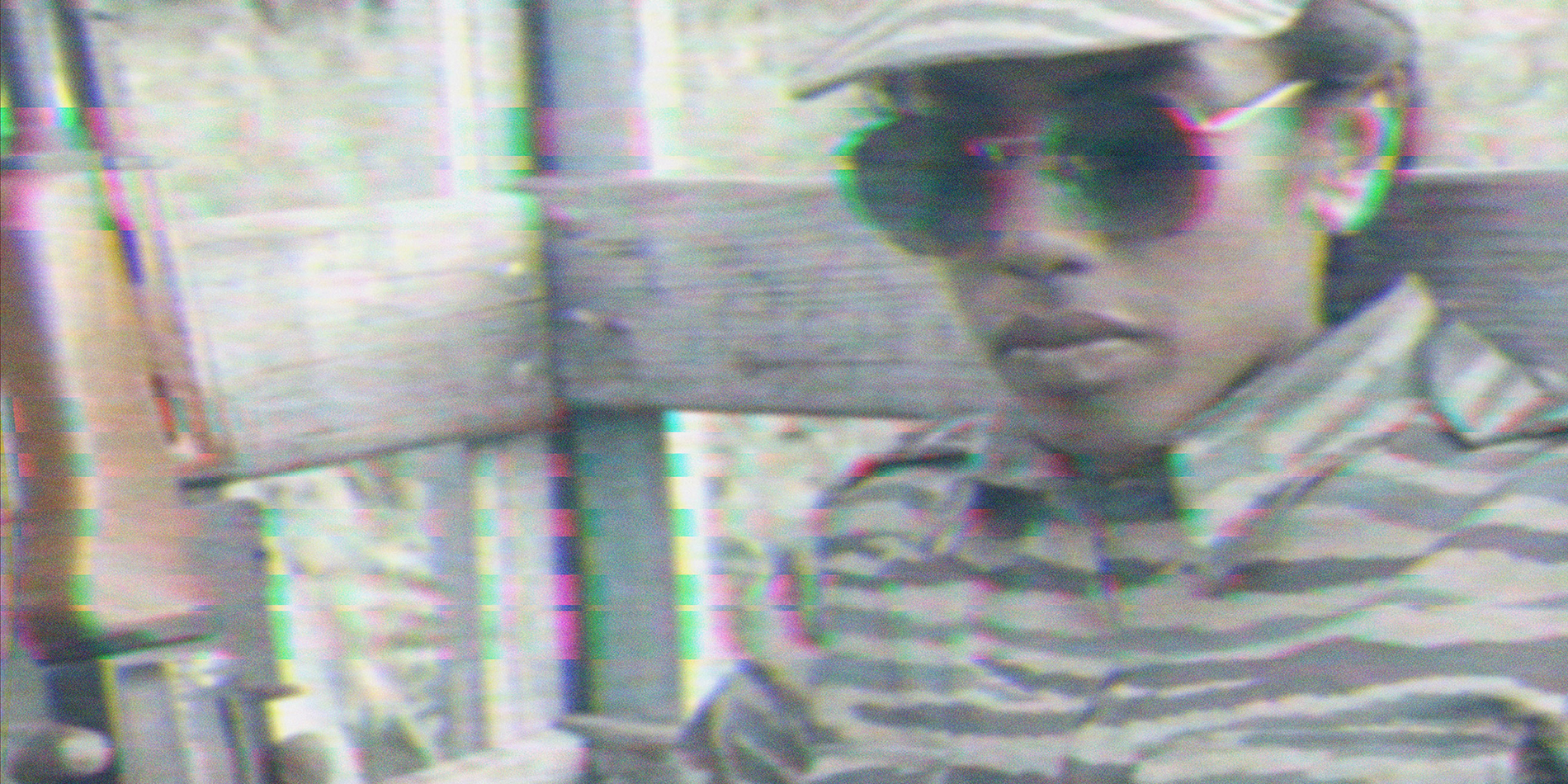

In The Finesse, the characters are spread out between the present of the video’s making and a specific moment in the Sri Lankan civil war that coincided with the 1994–95 OJ Simpson trial in the United States. The televised courtroom drama was widely watched, and it occasioned mainstream questioning into the production and consumption of truth and spectacle, at the national level and outside of the United States. In the video’s present, a deepfake Kim Kardashian reflects on the dissonance created by the proceedings of the OJ case from her front-row seat as defense lawyer Robert Kardashian’s daughter. She then propounds that her experiences as a media personality have also contributed to her sense of reality’s fabrication by power, asserting that this is second nature to stateless peoples like the Armenians, Tamils, Kurds, and Palestinians. The other conversant in the present day is a young unnamed dancer of Tamil origin who speaks of the diffracted experiences of displacement, belonging, and reclamation of cultural forms such as dance. Her ruminations are interspersed with archival footage from the Tamil liberation struggle, and along with the dialogue of Kulendran Thomas’s uncle, they are some of the videos’ most poignant passages.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, Being Human, 2019/2022. Installation view, Christopher Kulendran Thomas: Another World, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, October 22, 2022–January 15, 2023. Photo: Frank Sperling.

Finally, there is Manmahal, the luminary Tamil architect whose legacy the video unearths. She presents her work in rebuilding destroyed Tamil architecture and creating a decentralized networked system for establishing connectivity with the growing diaspora, while opining on the OJ debacle as an example of the many inevitable symptoms of representative democracy. Yet subject to further scrutiny, or an online search, Manmahal appears to exist only within Kulendran Thomas’s oeuvre, which includes publicly available funding proposals.4 To assert this is a risk, but one that cannot be foreclosed when dealing with art that funambulates between fact and fiction. More so than critical fabulation, the concept of parafiction may be the most suitable frame of analysis. Art historian Carrie Lambert-Beatty coined the term in 2009 in reference to contemporary art practices that flourished in the 2000s and actively sought to deceive their viewers at least partly or momentarily by presenting fiction as fact.5 Examples include artist Michael Blum’s conjuring of a Turkish feminist activist by the name of Safiye Bahar, the Yes Men converting Vienna’s Karlsplatz to Nikeplatz, and Walid Raad’s quicksand history of contemporary Lebanon through the Atlas Group.6 After the gotcha moment, if such a moment does take place, the viewer’s mind may perceive a glint of art’s dimensions and discontinuity with reality or be prodded toward balancing life-affirming trust with due doubt and diligence.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, The Finesse, 2022. Film still.

Lambert-Beatty remarks that in the abundance of parafictional practices, talk of “resistance” in political art was succeeded by talk of “intervention.”7 Throughout the 2000s, many artists turned from representing political struggle toward questioning the construction of accepted truth and hegemonic ideals through different forms of knowledge and media. This meant devising projects that sought to disrupt the public sphere—intervening in a busy intersection or radio program—and creating new forums, such as a roundtable or communal garden. Just outside the purview of the contemporary art institution was culture jamming and the Adbusters taking over Zuccotti Park. Artists felt and broadcasted an epochal malaise, but existing social movements limited the forms of political involvement that could have informed artistic practice. It was the era of a stalled but still standing post-1989 liberal consensus, which was marred by 9/11 and the United States undertaking the War on Terror (as Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, himself a jesting belletrist, pronounced the “unknown unknowns”). It is also, not incidentally, the same decade in which the Tamil movement for self-determination was reputationally besieged and militarily defeated. Political geographer and essayist Sinthujan Varatharajah stresses that the international support that shored up the Sri Lankan government against the Tamil people must be understood in light of that globally exported state discourse against non-state paramilitary actors of different stripes.8

The present moment into which Kulendran Thomas and Kuhlmann insert their interventions—by way of deepfakes pronouncing solidarity with the world’s oppressed, parafictional characters plucked out of the eroded archive, and others—is well removed from the height of the War on Terror. The previous decade saw the rise of the Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and Me Too movements, as well as the growth of prison abolitionism in the United States; the Arab Spring in various parts of the Southwest Asian and North African region; and the first and second Pink Tides in Latin America, to name but a few. Leftist movements, from the social-democratic to the communist, have attempted to reassemble, and the Right has bared its fangs and clamped down in response. Art will always claim autonomy—as it must—but its political stakes have come into sharper focus than they have in a long time. It feels slightly less relevant and more monomaniacal when artists claim that they are at their drawing boards or in meeting rooms engineering novel alternatives to the running order of things, rather than simply opposing said order.9 Perhaps the uptick in mobilization of recent years is what prompted Kulendran Thomas and Kuhlmann to portray more directly the liberation movement of yesteryear, fictively or not. Compared to Being Human and the artists’ older work, The Finesse goes deeper into the past of the liberation movement ostensibly in order to probe the ideological principles and technical ingenuities forged in its furnace. On the surface of it, there is both “intervention” and “resistance.”

Christopher Kulendran Thomas in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, The Finesse, 2019. Installation view, Christopher Kulendran Thomas: Another World, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, October 22, 2022–January 15, 2023. Photo: Frank Sperling.

It is worth noting, however, that The Finesse engages very little with the LTTE’s historically documented actions and policies or the perception of LTTE among Tamil individuals of different caste and class origins inside Sri Lanka and elsewhere. Indeed, the Tigers are barely ever explicitly named. I bring this up in light of two of the two videos’ concerns. First is the hegemonic Sri Lankan and international perception of Sri Lankan Tamils within the organization and outside of it as terrorists. Second is the possible form that self-determination for an oppressed racial group may assume in relation to the modern nation-state. The LTTE was not a separatist movement at the moment of its founding in 1972, when the Tigers still sought federalist autonomy. Demand for an independent state only became the official line in 1976, after escalating anti-Tamil violence and legislation. It was then dropped in 2004, as the LTTE lost ground. While the LTTE may or may not be thought of as the sole representative of the Sri Lankan Tamil people, that political formation’s own changing relationship to the state form may have proved relevant to the artistic endeavor at hand.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, The Finesse, 2022. Film still.

Kulendran Thomas and Kuhlmann’s work contains a separatism of another kind, what might be called a separatism from the Real. This form of libertarian technologist politics insists that it can counter dominant state-sponsored deception, and by extension the state form in its entirety, through even more relativism, this time bottom-up and against the state. But to assert that those are the politics of the artists’ work is to fall for the dupe. More aptly, this is its semi-ironic brand, crafted consistently throughout Kulendran Thomas’s oeuvre. It is continuous with the less subtly accelerationist New Eelam (2016–ongoing),10 which feels dated to the zenith of that discourse of the 2010s,11 before the more recent fever pitch of climate change and pandemic consciousness. In New Eelam, which is not included in the Another World exhibitions, the artists resurrected the Tamil motherland as a subscription-based flexible living platform. The service-cum-artwork was meant to prefigure a form of elective citizenship beyond present-day borders and their unpleasantries, with the accompanying faux commercial video stating that this innovation “need not feel like a political revolution.” The voiceover also proclaims that now that Amazon’s automation has surpassed the need for human labor power, the corporation is no longer extracting surplus and is effectively a non-profit, and “solidarity between workers no longer constitutes the revolutionary class.” The statements are simply too flippant to engage with directly. It seems a sound choice not to have included the video in shows that opened months after the Amazon Labor Union was formed, not because it would offend, but because the Real always returns to rattle louder than the artist’s solutionist sales pitch.

In The Finesse, the character of Manmahal speaks of “self-selecting communities of choice,” which she counterposes to existing systems of parliamentary representation and the party form. She asserts that “democracy is not about elections” but rather about “choosing between systems.” If this sounds not so different from the already-existing free will that an individual may exert if she has the means to fling herself onto the market and exercise choice, perhaps that is because it is precisely the same thing. Manmahal stresses that she is not against markets, because when the “markets are free from politics and corruptions, free from the elites of the ruling class, they will ultimately lead to collectivity.” Delivered by Manmahal to a foreign journalist visiting Tamil Eelam, these are seemingly the utterances of a movement intellectual and polymath. If viewers believe that the footage has been found in the archives rather than fabricated in the artist’s studio, and that the character is indeed a leading light of the movement, they are prone to listen with at least some credulity. The artists have here crossed from “giving voice” to the defeated into casual ventriloquizing. I found myself asking, Is it not enough to handle with epistemological humility the too-real quandaries and dilemmas of defeated struggle? Must the gruesome past be taken for a Rorschach tangle, molded into a megaphone, and used to propagandize in favor of the free market? Is it not pro-market forces that constantly transmogrify the state away from any downwardly redistributive function and into a night-watchman for private capital?

To say that Kulendran Thomas and Kuhlmann’s work abdicates realism sounds nostalgic, almost quaint, when faced with the deepfakes and algorithmically generated paintings on show. But if not a realism of representation and struggle, then what one may encounter is a Brechtian realism of the fourth wall that sheds light on artist-viewer-image relations and means of artistic production. Both of the main videos black out at key points, revealing, in The Finesse, a projection of the jungle of Tamil Eelam in reflection behind the viewer, and, in Being Human, the rest of the show in transparency behind the screen. The effect is stupefying, but it has the virtue of reminding the viewer that she is seated inside an art object that is immensely expensive. The exhibition’s roster of funders is long and comprises some of the usual stakeholders for an exhibition taking place in Berlin. The list also includes the Filecoin Foundation, which I at first naively took to be one of the copious counterfeits that populate the show. It turns out the Filecoin Foundation actually exists and is not to be discounted. It is currently developing the InterPlanetary File System, a decentralized file-sharing protocol in space, with the world’s biggest military defense contractor—Lockheed Martin—known for F-16 fighter jets and thermonuclear Trident missiles and for arming the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, Being Human, 2019/2022. Film installation, dimensions variable. Installation views, Christopher Kulendran Thomas: Another World, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, October 22, 2022–January 15, 2023. Photo: Frank Sperling.

Once more I found myself asking the peskiest questions: What do defense contractors defend? With whom do defense contractors contract? All of that stopped mattering when the artists’ earth.net website, which New Eelam’s old website now redirects to, told me, “Network protocols obliterate the ghost protocols of nation-states,” and “It’s giving euphoria-heterotopia intoxication-amnesia.”12 In Kulendran Thomas and Kuhlmann’s heterotopia, the wretched of the earth might become its entrepreneuring marketeers, mistaking the free movement of things for the free movement of people. Tragically, that switch-up is hardly ever a fiction.

Bassem Saad is an artist and writer born in Beirut and based in Berlin.