“Beware you who read, that your will is poison and your heart is pure. Otherwise this knowledge will destroy you. Be warned, do not read otherwise.”

This short statement appears in one of six vitrines scattered throughout the extensive exhibition Semina Culture: Wallace Berman and His Circle. Nearly hidden from view and written in fading lead pencil on the front endpaper of Eliphas Levi’s The History of Magic (1860), these are the words of Los Angeles artist Cameron (1922-1995). Surrounded by a nearly impervious gathering of literary and visual works (by forty-nine artists including Wallace Berman), Cameron’s obscured utterance serves as a comment on the state of Semina Culture. Bibliographically dense, the ephemeral fragments gathered in this exhibition are like footnotes to a larger text yet to be deciphered. We read these footnotes for indications of a counter culture, yet they are not easily translatable.

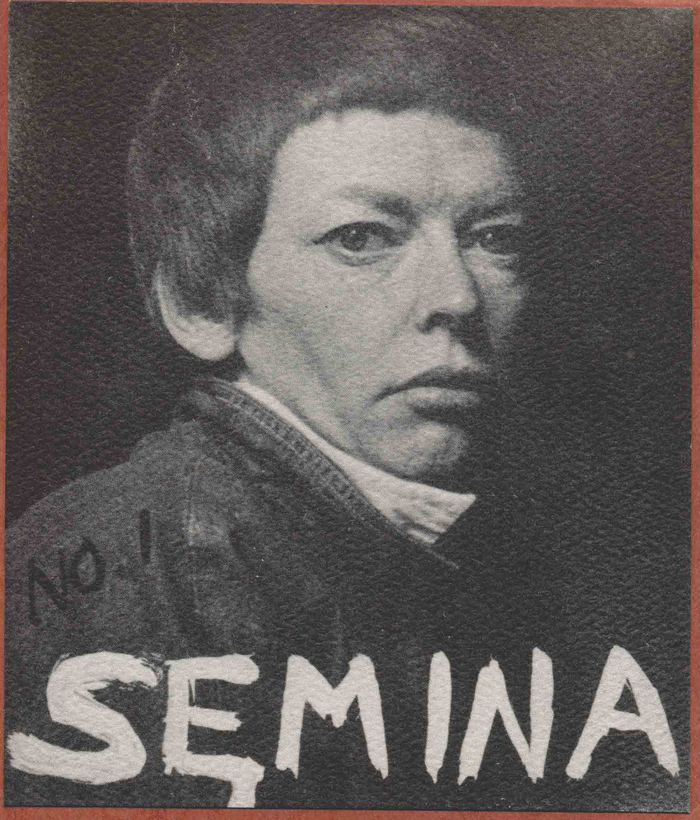

Semina Culture is an attempt by co-curators Michael Duncan and Kristine McKenna to outline the amoebic mass of people, literature, and artwork that surrounded, were influenced by, and contributed to Wallace Berman’s Semina. Semina was, in the words of Duncan, a “literary journal,” yet it can hardly be defined this easily.1 Nine manifestations of Semina appeared over the years 1955 to 1964. The literary contents of each issue were handcrafted by Berman on a letterpress, then cut-up, pasted or inserted into a bound booklet, a folio, or an envelope, and finally sent to colleagues. Lacking any editorial board, advertising, deadlines, coherent format, or stable of contributors, Semina was less a periodical than a means of communicating. Specifically, it was Wallace Berman’s form of communication, his organ to disseminate and circulate poetry, drawings, and photographs as small packets of ideas. Duncan and McKenna read Semina as a map of a network of artists whose work, from the mid-1950s to mid- 1960s, carried a similar “beat” aesthetic, each of them partially fueled by Berman’s erudite offerings.2 The exhibition, in its most coherent moments, is a physical manifestation of that mapped network. Such an exhibition concept seems straightforward, but the density of the rooms at the Santa Monica Museum reveals this project’s remarkable ambition. Duncan’s interest is in creating a succinct bibliography of Berman’s Semina, in which contributed texts and images were variously accredited to initials, illegible signatures, pseudonyms, or perfectly recognizable figures. Yet, the truest materialization of Duncan’s commendable scholarly project is in the catalog. On the museum walls, this bibliographic reading of Semina blends with Kristine McKenna’s discovery and recent (2004) reprinting of a previously unseen archive of photographic portraits Wallace Berman made of his peers and collaborators.

The exhibition begins in a small, three-sided room with works by Berman. Here we find one of his astounding Verifax works, Untitled A7-Mushroom, D4-Cross (1966): a large grid of fifty-six collaged squares, in which each segment contains the same image of a hand holding a transistor radio. The frame of each radio carries images of football players, mushrooms, Hebrew script, cheetahs, and other suggestions of the intersection between popular culture and a psychedelic spirit. Accompanied by drawings, collages, and two vitrines, this display presents a beginner’s guide to Berman. One vitrine contains published works with covers by Berman (such as a 1974 edition of Mallarmé’s Igitur), as well as mailers to colleagues most closely associated with Semina (such as Michael McClure or Robert Duncan and Jess). The second vitrine contains all nine embodiments of Semina. Though each is displayed, certain issues are left closed or incomplete, and therefore unreadable. Semina Two, one of the rare bound issues, is held open for one page, which contains the bizarre surrealist photograph of a beached dead shark contributed by the late Walter Hopps. There is Semina 3, its only contribution a foldout sheet with McClure’s Peyote Poem, closed for its cover—Berman’s photograph of two peyote buttons. David Meltzer’s The Clown, which was printed on a series of cards and inserted as the sole piece in Semina VI, is similarly left in a stack, leaving only its first card to be read.

Semina is the core of the exhibition, and the limited access to it, the fundamental text of Semina Culture, undermines what lies at the creation of that culture. Semina is what feeds into the remainder of the exhibition, infecting and affecting a winding display of Berman’s peers across the halls of the Santa Monica Museum. Yet how one moves from Berman’s Semina to these peers is a leap of faith. Forty- eight artists, photographers, writers, poets, and a curator (Hopps) are included herein. Each figure is granted wall space with at least a photographic portrait (often from Berman’s recently discovered store of negatives) and a short biographical text explaining his or her relationship to Berman. It is hard to move beyond such a broad and vague criteria as the motive of including each of these figures, and one must understand Berman to have known more than forty-eight people. The coherence of the group displayed is uncertain; they are not all contributors to Semina, were not all photographed by Berman, are not all from the West Coast, nor do they all share this alleged “beat” aesthetic. The exhibition is an extensive, and nonetheless well-researched view, but the only commonality of the exhibited is that they were, simply, a selection from the culture of people that surrounded Berman. There are those unforgettably necessary to Semina: McClure, Robert Duncan, Jess, Hopps, George Herms, Charles Brittin, and Robert Alexander (who taught Berman how to use a letter press); the odd group of Berman’s friends who were all once child actors: Bobby Driscoll, Dean Stockwell, Billy Gray, Russel Tamblyn, and Loree Foxx; the drug-addled, now nearly unknown proto- feminist Los Angeles artists Cameron and Aya (Tarlow); and a group of New Yorkers who drifted through Berman’s Topanga Canyon House: Diane DiPrima, Taylor Mead, and Jack Smith; among many others.

Though not peers of Berman, there are those contributors to Semina whose texts are restricted in the exhibition, and altogether absent from the accompany catalog. The importance of Herman Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game (1946), a work redolent of Berman’s curiosity for the encoded nature of language, is effectively lost. Exhibited hidden beneath other pages of Semina Two, Berman includes a passage from Hesse’s work; “Like constellations crystalline they echo, Life dedicate to them takes purpose on, And none of us can fall from out their courses, If not toward the holy colophon.” Peers close to Berman are omitted—where, for the mere fact that he filmed Taylor Mead for his lead in Tarzan and Jane Regained…Sort of at Berman’s home, is Andy Warhol? An even greater anathema, since he contributed to Semina Two with the poem “Mine,” is Charles Bukowski. Exclusions such as this seem a grave mistake. Excluded, perhaps, to maintain an assumed “beat” aesthetic, yet such a style is not defined, questioned, or clarified by the content of the exhibition. Semina Culture does not entertain such critical questions, and has ample opportunity to do so. As it is, these others hang on the outskirts of the exhibition as beacons that break up the Eisenhower-era portrait of Berman-as-godfather the curators attempt to uphold. Berman is much more mysterious than this, and his aesthetic (across Semina and other works) outruns any recognizable, generic appearance. Those he inspired through Semina may be unknown for a reason, and others remain known as they shared the unique qualities of this art historical pariah.

Walking through the exhibition, we bend and squint. Vitrines filled with books, mailers, notes, doodles of image and poetry, are accompanied by choice paintings (such as by Joan Brown or Jay Defeo), forgettable efforts (such as Henry Miller’s quasi-Chagall watercolors), and Berman’s photographic portraits. Berman was an adequate photographer and his portrait of a bare-foot Topanga Canyon George Herms is a square depiction of a dear friend. Other images are not nearly as memorable. Semina, however, was Berman’s true fix. Berman’s tract is a readymade curatorial effort, an exhibition in codex, which relies on a literary sensibility and its intersection with photography and drawing on the printed page to communicate thoughts and impressions. The curators of Semina Culture expand into directions Berman chose not to, ignoring the boundaries of Semina for a broader, less refined look. The most commendable works in this exhibition are by those artists Berman had already gathered, now fifty years prior. Viewing the exhibition with blinders, and concentrating on those twenty-one participants in Semina present here, one realizes the curatorial significance of Berman’s irregular publication and the failed elucidations of Semina Culture. Many of Semina’s contributors were, and may remain, eclipsed by history.

Semina Culture is one of the most comprehensive attempts to unlock some of the mystery of Wallace Berman, and the first attempt to decode the man through the logic of his peers. Yet Berman knew that language was the ultimate mystery, the code that, like the Hebrew lettering he often employed in his work, could never completely translate, in Maurice Blanchot’s words, “the pure joy of passing from the night of possibility into the daytime of presence.”3 The conundrum of written semiotic code was a mainstay across Berman’s career, an enigma ironically (and perhaps accidentally) suggested here by the plethora of texts exhibited beneath shut covers, writ in scrawled handwriting, or simply encoded in the fervent trappings of the authors. (For instance, Cameron’s text, quoted above, ends “T∴O∴P∴A∴N.”) Cameron’s petition for illiteracy infected the curators of this exhibition, but reading was, for Berman and many of his peers, the key to unlocking an esoteric nature far beyond the practicalities of a definite culture.

Chris Balaschak is a writer and curator living in Los Angeles.