REDCAT (Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater) sits immediately adjacent to the third level of the parking structure underneath the Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles. This parking lot provides one of two entrances to REDCAT and is central to John Knight’s recent exhibition there. As the wall text in the lobby outlines, REDCAT was an afterthought to the initial plans and construction of the Walt Disney Concert Hall, carved out of the already built parking structure. The REDCAT Gallery was an additional afterthought, a hardly deliberate extension of the lobby. Although the Frank Gehry team was called back to consult on its design, the gallery space is barely articulated as such.1 The entire affair—concert hall, parking lot, theater, café/bar, and gallery—reflects a crucial but unremarkable choreography of bureaucratic prioritizations and administrative crisscrossing, characteristic of such large-scale projects.

More than a decade after the completion of Gehry’s “living room for the city”2 and its coda, REDCAT, the “cultural corridor” now includes The Broad museum, another media-friendly architectural landmark and yet another attempt to “rehabilitate Downtown Los Angeles,” which has proved to be undeniably successful by their standards. It’s difficult to speculate on the forces that drive the “urbanization” of the city, producing the kind of desire that expresses itself in long lines around The Broad, or attendance at a DJ night at Hauser Wirth & Schimmel. At the very least, these scenes illustrate a strategic and coercive reconstitution of the image of a public in Los Angeles and present a hierarchical schema that underlines a massive disparity in the distribution of attention-value—one where REDCAT’s quaint presence seems to be on the losing side (a fact proven by the walk past the perpetual line at The Broad into the always nearly deserted REDCAT gallery).

John Knight, A work in situ (2016). Installation view, REDCAT, Los Angeles, April 9—June 12, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and REDCAT. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

Knight’s installation mimes the organizational forms of the parking lot, consisting of text painted on the walls, floor, and support columns of the gallery in the same—or at least similar enough not to be able to tell the difference—lavender-like paint that is used to distinguish the third-level parking from the rest. The font that appears in the parking lot, designed by Bruce Mau specifically for the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Walt Disney Concert Hall, is also used in the installation.3 Knight’s texts satirize the directional language and shapes that are typical in spaces where functionality serves as a primary quality, by employing figures of speech that share a similarly assertive tone but lack the operational logic necessary to get people on their way. For example, the text on the northeast wall reads “TAKE IT FROM THE TOP” —a declaration most commonly used in music, where a conductor instructs the band, or orchestra, to start from the beginning of the piece. The statement can also be considered in the language of economics as a practical solution to income inequality, a refrain that has recently entered dominant political rhetoric as per the bolstering of the “99%” by the presidential campaigns. (“OCCUPIED,” painted high up near the ceiling, seems to refer to the same historical circumstance alongside its territorial intimations.) An arrow points to the top-right corner of the wall, in the direction of the concert hall, as if to say “from there,” further narrativizing the already spatialized top-down relationship between the two institutions.

John Knight, A work in situ (2016). Installation view, REDCAT, Los Angeles, April 9—June 12, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and REDCAT. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

“CURB APPEAL” is painted on the floor beneath one of the two columns, evocative of countless real estate “flipper” themed television shows, playing smoothly into the “development” content of the exhibition. It’s also the title of a previous work by Knight (Curb Appeal, 1966/2012), which was installed during the 2012 Whitney Biennial on what is now the former Whitney Museum building, designed by Marcel Breuer. According to the Whitney website, Curb Appeal was Knight’s attempt to “spruce-up the façade” before the Metropolitan Museum took over the space.4 The occurrence of double meanings or multiple references—again exemplified by the text “ADDITIONAL FOUNDATION SUPPORT,” which punningly collapses financial and structural support into a singular entity—stands in contrast to the streamlining signs in the parking lot—the crème de la crème of utility—which contract the field of possible identifications to a single position (the subject who needs to find a parking space or the car or the exit). Instead, the installation acts as a sardonic model of the identificatory effects of design, diversifying the sequence to pathologically point elsewhere and, as a result, causing the implied subject position to bloat. It is noteworthy that Knight achieves this without relegation to the familiar vapor of text-based work, opting to keep intact the cultural connotations of each sentiment alongside the proliferation of its signifying means (most of which still maintain some tie to the circumstance of the exhibition—à la in situ), rather than to procure their instability through a generalized mystification.

In his review of the show for the Los Angeles Times, David Pagel suggests that the installation provides the viewer with a trans-historical experience, stating “To step into ‘A work in situ (2016)’ is to travel back in time—to that moment after the parking structure was constructed and before a section had been converted into REDCAT.” He goes on, “The first thought that enters your mind when you step into Knight’s installation is that you have lost your way—that, somehow, you have gone through the wrong door and ended up back in the parking structure.“5 Pagel’s description of one’s initial encounter provides an inflationary account of the simulacral qualities of the installation and assumes the folding of the work into the simple fact of the gallery’s previous state, leaving the viewer immersed in its deceits. The implied effect is reduced to a pseudo-revelatory engagement with REDCAT’s not so unique history, in a city where, as Allan Sekula wrote, “Parking is king,“6 and where most parcels of land are used as parking lots prior to further development, only to be at risk of being turned back into one after the fact, as testified by the status of the long-standing downtown DIY space, The Smell.7 As if, in Los Angeles, parking might be the constant condition against which all transformation is measured.

John Knight, A work in situ (2016). Installation view, REDCAT, Los Angeles, April 9—June 12, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and REDCAT. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

Aside from the paint color and font, Knight’s installation could at best be described as a suggestive approximation rather than a direct appropriation of the parking lot, as is demonstrated by the obviously out-of-place language and key differences in the application of the signs. The support columns are the most obvious digression: the parking structure uses black adhesive vinyl against lavender paint, while Knight’s install uses only the purple paint and its inverse. This stylistic differentiation privileges the sign value of the generalized form of the parking lot and the capacity of the viewer to fill in the blanks, suitably anchoring the work to the particularities of the site without collapsing in onto itself (or us). Which is to say, the distinction between the two spaces (and the cultural value that enforces this difference) remains firmly intact and no one is made to think otherwise. This doesn’t mean that the work entirely sidesteps the pitfalls associated with a narrow site-specificity, that is, the kind of D.O.A. criticality that such superficial comparisons propose. If anything, this effect is exaggerated, illustrating not only the exhibition’s function as a quasi-mirror to its context, but also its configuration as a culmination of forms that refer (and are subservient) to an art-historical milieu of which Knight is a part. This operation gives form to the exhibition as a whole, by highlighting the inseparability of the critical gestures and their historicization with a kind of dry self-reflexivity (remember “CURB APPEAL”). The work enacts a double bind, in which such forms are both undermined and inscribed, which provides the foundation for drawing connections outside of the framework of the installation.

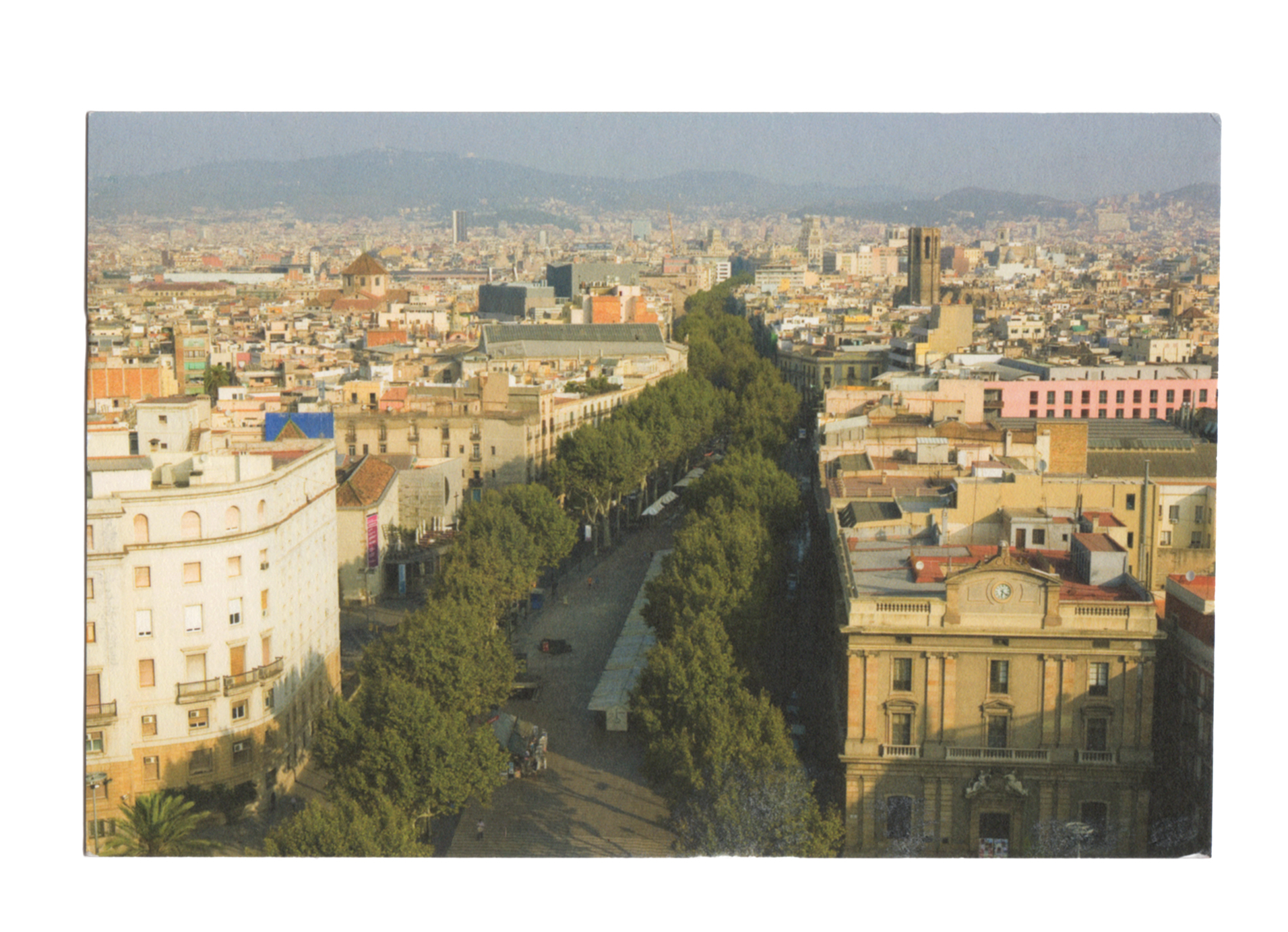

Such connections emerge through the deployment of a recurring trope of Knight’s work: the extension of the exhibition site into publications or—as demonstrated in this show—a postcard, thus engaging a reorientation of the notions of primary and supplemental sites of artistic activity. For A work in situ (2016), the photograph on the postcard presents a view looking down on La Rambla (captioned with the Catalonian plural “Les Rambles”), a tree-lined street in Barcelona that has become a central tourist trap (comparable to a smaller scale Hollywood Boulevard or Times Square) ending at a monument to Christopher Columbus overlooking the sea. What’s noteworthy about the image is that it’s the first one that appears in the (Google) search results for “Les Rambles” (at the time of writing8), and it serves as the main image for the Wikipedia article for the street (albeit cropped to fit the dimensions of the postcard)—as if to nod to the now commonplace extension of the explicative experience of art viewership into online sources, while simultaneously indulging in its capabilities.

John Knight, postcard accompanying A work in situ (2016). REDCAT, Los Angeles, April 9–June 12, 2016.

It becomes apparent (after a once-over of the Wiki article) that the image is taken from the vantage point atop the Columbus monument, which was erected in honor of his discovery of the “new world.” The implication of the genocidal depredations of colonialism (and its celebration) is exacerbated by the positioning of our elevated gaze, overlooking a street that has only recently experienced a dramatic shift due to a tourism industry—analogizing the effects of colonial conquests with the corrosive movements of capital.

In some ways the postcard image constructs a similar viewing experience to that of Knight’s work 87° (1997–99) at Storm King Art Center: a telescope overlooking the outdoor sculpture garden that, when looked through at its titular position, reveals a water tower outside the institution’s perimeter. The site of ideological culmination (the “artwork” / the Columbus monument) serves as the platform for viewing a site of production/consumption (the water tower / La Rambla); the symbolic synthesis of the two is actualized primarily by our field of vision. Likewise, this perceptual marriage is re-performed at the scale of the exhibition itself, correlating the content of the postcard with the allegorical parking lot.

John Knight, A work in situ (2016). Installation view, REDCAT, Los Angeles, April 9—June 12, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and REDCAT. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

The exhibition is configured as a representation of its relational capacities: i.e. the relationships between the exhibition/REDCAT and the parking lot, the parking lot and the Walt Disney Concert Hall, the Walt Disney Concert Hall and the development of the “cultural corridor,” contemporary art and the development of the “cultural corridor,” contemporary art and the larger gentrification of downtown Los Angeles, etc. The pairing of these with the complex of relations presented by the image on the postcard constructs a formulation that could lead one to the end-all provocation that contemporary real estate development and the gentrification it fosters is somehow comparable to the colonial atrocities of Columbus and those who followed. Although this read is certainly fruitful, the figurative and actual distance of the constituent parts of the display (the postcard inconspicuously resides on the desk outside of the designated gallery) and the multivalent content of the text together place emphasis on the procedural operations (such as looking) that produce such correlations, as opposed to the absolute comparability of the two disparate histories.

Primacy is placed, then, not on the delineated sites of reception (exhibition, postcard, wall text) and the content they comprise, but rather on the eyesight that enforces their connection, situating us, and our cognitive faculties, as collaborators. This operation differs from the melancholic admissions of complicity epitomized by some of art’s boosted careers, which amount to little more than crooning the inescapability of dominant organizing forces (the market, capitalism, power, etc.) through a not so arduous (“performative”) participation in their circular mechanisms. Knight instead offers a survey of the processes that solicit our entanglement, and by virtue of this articulation—and as testified by the text that points to an alternative exit to the street—suggests the possibility of “ANOTHER WAY OUT.”

Bedros Yeretzian is an artist in Los Angeles. He is also a contributing member of the bands Behavior and Purity.