Whatever went through Harold Gregor’s mind upon seeing Carl Andre’s contribution to the Primary Structures show in 1966, it didn’t have much to do with Minimalism. At least not judging from his document Everyman’s Infinite Art, or from the things Gregor was doing and saying back then or that he says more recently in the interview published in these pages. Gregor’s interests weren’t those typically associated with Minimalist sculpture—its famous eliminating of internal relationships so as to embed the art object more insistently in its immediate spatial and temporal context, thus leading to a heightened awareness of the contingency of perception, etc. (Months before Gregor concocted his show, Lucy Lippard had already pronounced Minimalism “a new cliche.”1) Instead, what seems to have motivated Gregor was the utter disembeddedness of Andre’s Lever, at least the version he encountered, a photo reproduction above a caption (“Carl Andre, Lever, firebrick, 360″ x 4″ x 4″, 1966″) illustrating an article in Artforum. Indeed, striking parallels exist between Gregor’s response and a much more renowned information-based show mounted at exactly the same time. Mel Bochner’s Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed as Art, a stockpiling of artists’ written notes, studio sketches, instructions, receipts, and other preparatory or ancillary materials, was also conceived as a Christmas exhibition in a college gallery (New York’s School of Visual Arts) by one of its faculty members (Bochner taught art history there). By coming up with a reproducible document, a catalog about a show rather than the show itself, Gregor, like Bochner, prioritized what Seth Siegelaub would later call secondary over primary information (prioritize indeed—Gregor printed and mailed out 500 copies). Maybe artists in a fledgling secondary market like Los Angeles (it was in 1962 that Leo Castelli established collaborations with the Dwan and Ferus galleries in Los Angeles, as well as with Ileana Sonnabend in Paris) held a particular fondness, if not outright need, for secondary information. But even New Yorkers had to admit at the time that “art is spread in an exploded and non-hierarchic world…distributed in a network of communications,” as Guggenheim curator Lawrence Alloway described it, again in 1966.2 The over-accommodation of communicational mandates was one of Michael Fried’s famous complaints in “Art and Objecthood” (which he started writing in—that’s right—1966). Minimal art, Fried huffed, “seeks to declare and occupy a position-one that can be formulated in words and in fact has been so formulated by some of its leading practitioners.”3 By the time Conceptual art fully blossomed a few years later, even this idea seemed old hat. By 1969 Siegelaub shrugged that “for many years it has been well known that more people are aware of an artist’s work through the printed media or conversation than by direct confrontation with the art itself.”4 Just like that, Primary Structures had ushered in the reign of the secondary.

David Bourdon, “The Razed Sites of Carl Andre: A Sculptor Laid Low by the Brancusi Syndrome,” Artforum 5.2, October 1966, p. 15.

One result of elevating the secondary over the primary and of deemphasizing the viewer’s physical “co-presence” with a material object is that artworks were made less reducible to a logic of ownership or title transfer. “When someone ‘buys’ a Flavin he isn’t buying a light show,” Joseph Kosuth argued in 1969, “for if he was he could just go to a hardware store and get the goods for considerably less. He isn’t ‘buying’ anything. He is subsidizing Flavin’s activity as an artist.”5 Gregor says much the same a few years earlier in Everyman’s Infinite Art, using the word “patron” instead of “collector.” As Grace Glueck quoted Gregor in the New York Times, “It minimizes the gallery function—the work need not be bought as the patron can make his own. It minimizes the artist’s function—no skill is needed to make it. And it minimizes the critic’s function—it is practically devoid of content, thus any interpretation seems appropriate.”6 (You can almost see the light bulb throbbing over Lawrence Weiner’s head as he browsed the newspaper that morning.) Compared to ownership, patronage more fully acknowledges that the assets being acquired are not just material but also immaterial and social; unlike in the marketplace, where maker and buyer remain strangers and ownership transfer is instantaneous, with the projects and contracts of Conceptual and post-studio art there’s a sociality that necessarily overflows the underspecified and inadequate frameworks of such contracts. At the same time, in response to Conceptual art’s defiance of the established conventions of exhibition—including the standardized white cube that Minimalism, in its site-specific or architectural ambitions, had appropriated—museums and galleries were forced to adapt. Indeed, both Minimal and Conceptual approaches encouraged institutions to be more cooperative toward artists’ initiatives and ideas, resulting in more dialog and give and take between makers and presenters. The subsequent rise in artists’ projects and commissions knitted the spheres of production and institutional reception into a more intimate, responsive collaboration. Not only did artists write proposals, stipulating terms and conditions and itemizing materials, but contracts themselves were presented as artworks. (Again, this starts before the appearance of Conceptual art proper; think of Robert Rauschenberg’s Portrait of Iris Clert, 1961, or Robert Morris’s Document, 1963.) So here is another prescient aspect of Everyman’s Infinite Art—besides an exhibition catalog and a manifesto, it also resembles a business contract, with its indented, numbered and lettered itemizing of stipulations and rules, and culminating with Gregor’s signature entered just above his printed name and title, all accompanied by Chapman College’s official school seal.

Mel Bochner, Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed as Art, 1966. Four identical loose-leaf notebooks, each with 100 xerox copies of studio notes, working drawings, and diagrams collected and xeroxed by the artist, displayed on four sculpture stands. Courtesy the artist.

Mel Bochner, Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed as Art, 1966. Four identical loose-leaf notebooks, each with 100 xerox copies of studio notes, working drawings, and diagrams collected and xeroxed by the artist, displayed on four sculpture stands. Courtesy the artist.

Robert Morris, Document, 1963. Typed and notarized statement on paper and sheet of lead mounted in imitation leather mat, 17 5/8 x 23 3/4 in. Gift of Philip Johnson. © 2011 Robert Morris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Everyman’s Infinite Art is thus post-studio, it embraces a decentralized art world, it privileges secondary over primary information, and has as its base of operations an art school. Sounds like it was made today. Except for one thing: today we tend to hide the contract. The rise of relational aesthetics and social sculpture means that we treat secondary information as if it were itself primary. We replace written captions and criticism with talk and hanging out; we imagine our institutional settings and disciplinary discourses to be the natural offspring of spontaneous socializing, an organic and immediate phenomenon animated with breathy laughter and whispered talk, filled with sensuous, creaturely comforts, as natural, authentic and everyday as sharing a beer and consuming a meal of pad Thai. We pretend that art doesn’t exist within, and doesn’t need, any frame. Just like that, the reign of the secondary surrenders to its own thorough mythologizing and aestheticizing.

Harold Gregor, Illinois Corn Crib #25, 1974. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 43 x 66 in. Bank of America.

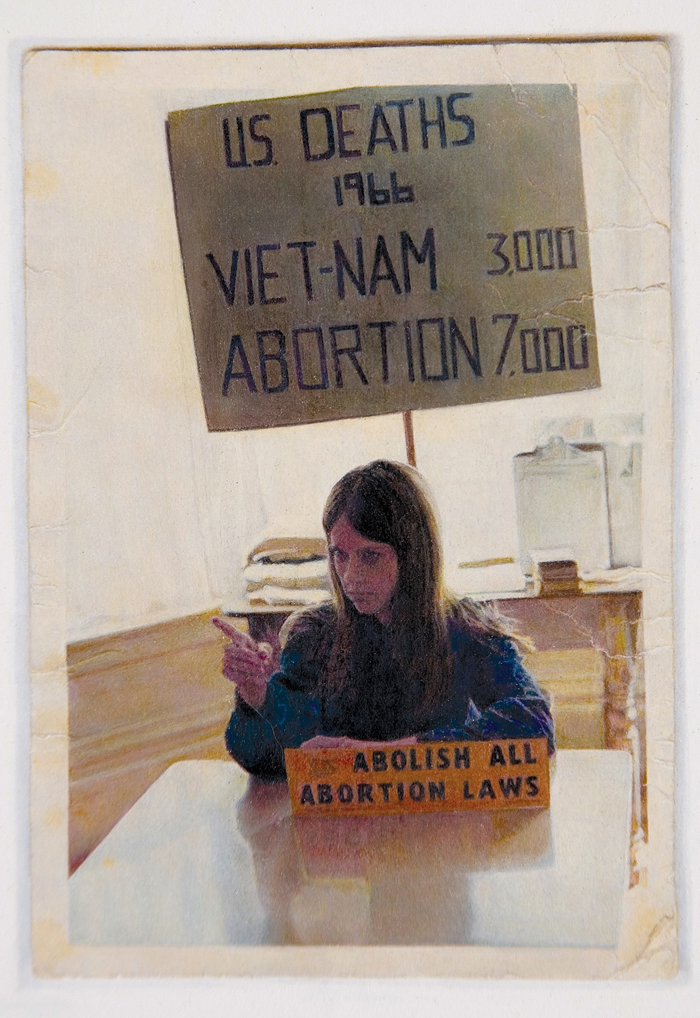

Andrea Bowers, Young Abortion Rights Activist, San Francisco Bay Area, 1966 (Photo Lent from the Archives of Patricia Maginnis) (detail), 2005. Color pencil on paper; paper size: 50 x 38 1/4 in., frame size: 52 1/2 x 40 3/4 in. Courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Photo: Joshua White.

Judie Bamber, Mom with Tan Lines #1, 2007. Graphite on paper, 15 3/8 x 18 3/16 in. Courtesy of the artist and Angles Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

From looking at Everyman’s Infinite Art you’d never guess that Gregor devoted almost his entire career in opposition to communicational mandates. That is, he made, and still makes, photorealist paintings. While such an approach is also to a certain degree egalitarian (anyone can copy another image), here the photograph is treated not as facile information to be deployed and instrumentalized. Rather than weightless and event-like, compliantly modular and easily fragmented, on-the-spot and just-in-time, photography is instead appreciated for its intransigence; it is treated slowly, with a forensic labor that fixates on but is also somewhat paralyzed by its object. By spending hours on end exercising only a few small bones in the fingertips, the artist begins to look as frozen in place as the photographed scene he’s translating. The required commitment of labor and time is intense but also narrowed, limited to a small slice of isolated photographic evidence. This kind of solitude and fidelity appears to us today as anachronistic, strange, even uncanny—and that may be why a lot of younger artists are turning to it. Take, for example, what’s been called “re-enactment art,” like Jeremy Deller’s Battle of Orgreave (2001), a restaging of Thatcher-era clashes between British mine workers and police, or Mark Wallinger’s State Britain (2006). Closer to home (and more within the scope of Pacific Standard Time) examples include Judie Bamber’s mesmerizing renderings of old family photos and Andrea Bowers’s use of historical documents pertaining to sixties feminist activism. In contrast to Gregor’s work, the orientation in this more recent art is retrospective, the artist’s gaze by turns fascinated and melancholic. The starting point is a document of an irretrievable “what-has-been,” a past moment that while it stays with us into the present does so only hauntingly. (Bowers’s work especially signals a desire for access not only to the past but to action, to activism—while in terms of subject matter her preference is for people who experience not information’s freedom and mobility but rather its greater administration, politicization, and restriction.) Copying a photograph doesn’t bring the past to life; it instead repeats the camera’s powers of estrangement, its indifference and distance. Redrawing this trace of history expresses both a desire for continuity and immediacy and also the impossibility of that desire, its perpetual frustration. Whereas a contemporary cyber- conceptualist might say that secondary information wants to be free, here photography is characterized as not free, as not just in time and on demand. It’s instead about belatedness. It’s more dumbstruck than mobile, more fixated than free. And so another twist, as the aestheticizing and naturalizing of Conceptual art by relational aesthetics seems to confront a backlash. Say hello to the zombies of the secondary.

Lane Relyea is Associate Professor of Art Theory & Practice at Northwestern University and editor-designate of Art Journal (for a three-year term beginning July 2012). His book DIY Culture Industry: Social Networks, Signifying Practices and Other Instrumentalizations of Everyday Art will be published by MIT Press in Fall 2012.