In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, geologists began to name geological periods—the history of the earth—based on the chronological layering of rocks and organic matter. Although the dinosaur-dominated Mesozoic era is most familiar, the subsequent Cenozoic era, whose name means “recent life,” is marked by the procession of the “cene” epochs, which culminate with what has been provisionally called the Anthropocene, the geochronologic period dominated by human activity. Pending ratification by the International Union of Geological Sciences, the “Anthropocene” is an epoch-in-waiting. Not even its starting point is agreed upon: the spread of agriculture and deforestation, the “Columbian Exchange” of “old” and “new” world species, the Industrial Revolution, or the mid-twentieth century?1 Still, the term so effectively gives temporal form and meaning to the contemporary experience of living in a world where human acts have shifted even the climate that it has met the embrace of a range of non-scientist thinkers, artists, activists, and public policy planners.

Now deep into the Anthropocene, can we imagine a way out of it, beyond humanity’s climate-changing activity? Our carbon-freeing momentum hurtles the world toward a tipping point, with rises in temperature and sea level that, although measured in single digits now, forecast larger effects and enormous events: polar ice melt, coastal inundation, drought. No way out, it seems, but Tomás Saraceno imagines a different way—up—floating into what he calls the Aerocene. Saraceno’s Aerocene dodges the controversy surrounding the geochronologic nomenclature by hypothesizing a time beyond the Anthropocene when the record of human activity will be laid not upon the earth but in cities floating in the air. If most environmental planners envision earthbound adaptations to climate change—a world of towers, barges, sea gates, desalination plants, and mass population movements—the Argentine-born, architecture-trained artist relies on more delicate models—“the intricate structures of soap bubbles and spider webs”2—air dwellers that escape the earth. Stillness in Motion—Cloud Cities (2016), a site-specific installation that anchors Saraceno’s San Francisco Museum of Modern Art exhibition of the same name, summarizes the artist’s response to the decline of life on earth and attempts to free our minds of the earth, at least for the moment. The exhibition is, in effect, a retrospective of Saraceno’s Aerocenic interventions all packed into a single gallery. In addition to Stillness in Motion, the artist exhibits a set of drawings and a sculpture produced in partnership with spiders, a video demonstrating the technological foundation for floating cities, and a sculptural approximation of a floating Aerocene structure. These evoke, more than reveal, Saraceno’s proposal. There are no floor plans, no descriptions of Aerocenic living. But if the stakes of the exhibition are as Saraceno lays out—an “invitation to shape a post fossil-fuel epoch”3—then this omission might inspire visitors to conceive other radical resolutions of fossil-fuel dependence.

Tomás Saraceno: Stillness in Motion—Cloud Cities, installation view, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, December 17, 2016–May 21, 2017. Photo: © Saul Rosenfield 2017.

Making Small to Fit a Big Idea

Stillness in Motion, experienced as a sculpture and a model for the networks of human connectivity inherent in Saraceno’s Cloud Cities, reveals the elaborately conceptual underpinnings of the artist’s environmentalist vision without compromising an embodied aesthetic and affective experience. The installation—“a cloud of 10,000 nodes”4—links a half dozen polygonal structures. Each structure is studded with cords that radiate to other structures and nodes, forming a matrix that stretches to the 18-foot-high ceiling, the walls, and the floor of the 47-by-59-foot gallery. Suspended above the ground within the matrix, the structures are two to six feet in diameter, and several contain smaller polygons within them. Some of the structures are partially walled with transparent plastic or stainless steel, which at some moments reflect the ceiling lights and at other times mirror objects or people in the gallery.

As curator Joseph Becker puts it, Saraceno “conjur[es] an era in which humanity has ceased to negatively impact our planet and instead inhabits sustainable airborne structures that exist in symbiosis with nature and the atmosphere.”5 On his website, Saraceno elaborates, “When these structures become large enough…they will be able to carry massive payloads, and remain aloft, as long as the temperature within is one degree warmer than the outside air temperature. Cloud Cities will no longer rely on the power of the Sun and the Earth, but on the simple breathing of the creatures that inhabit it.”6

Becker places Saraceno within the lineage of Buckminster Fuller—who proposed floating cities in the 1960s—and a range of other “visionary precedents,” including the “structural explorations of the Argentine artist Gyula Kosice,” the “fictional universes of the Italian writer Italo Calvino,” the “futuristic urban visions of the London-based architectural group Archigram,” and the “multidisciplinary, countercultural projects of the Bay Area artist collective Ant Farm.”7 These thinkers have imagined beyond obvious solutions and even existing technologies, edging toward utopia and science fiction. So it makes sense that Saraceno’s immersive model of cloud-like cities that hover above the Earth, moving freely from one place to another, should materialize to museum visitors as fantastic, a cross between the constructions of a sci-fi movie set designer and the fabrications of a Tinker Toy fanatic.

If this seems theatrical, it’s only because Saraceno’s installation uses humble materials in sophisticated ways to transform the gallery into a constructed setting: topographically complex “systematic landscapes,” to use the term of another artist/architect, Maya Lin. Stillness in Motion recalls, in particular, Lin’s installation Water Line (2006), a web of aluminum tubing that renders the undersea topography of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Like Saraceno, Lin endeavors to create works that, according to Systematic Landscapes curator Richard Andrews, “offer a point of entry into our experiential relationship with the natural world…predicated on the belief that a connection to nature is an essential component of our humanity.”8 Both Saraceno and Lin depict, within the gallery’s bounds, spaces so enormous that they comprise worlds unto themselves. But neither approach reduces these spaces to simple replicas of topography—or to the didactic and activist goals of the artists. How do they accomplish this task? One measure of the success of installations such as Lin’s and Saraceno’s is the willingness of visitors to engage in an imaginative interaction that reframes the false dichotomy of mind and body. We enter Saraceno’s galaxy by foot, as it were, and accept its terms as both abstract sculpture and model for living. In this fusion of understanding and embodiment, visitors achieve the experience of virtual reality without the necessity of an electronic interface.

Maya Lin, Water Line, 2006. Installation view, Maya Lin: Systematic Landscapes, de Young Museum, San Francisco, October 25, 2008–January 18, 2009. Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

As with all architectural scale models, both Lin’s and Saraceno’s installations require viewers to imagine themselves small in order to transport themselves into these constructed worlds. In fact, as anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss suggests, all figurative artworks are scale models, if not always literally miniature in size then minimized by the reduction of the real object to its metaphorical representation. The magic of such a scale model, Lévi-Strauss says, is in its “renunciation of [its] sensible dimensions” in exchange for “the acquisition of intelligible dimensions.”9 It’s arguable, in fact, that the viewer’s imaginative insertion of self into the artwork would enhance all art viewing, intensifying the intelligible dimensions that the artwork represents. But if the effort to “enter” a painting in this way might daunt a museum visitor, Stillness in Motion and Water Line both have an advantage: to enter the gallery is to enter the work. These works are multiplicitous. They replace one set of sensible dimensions—city in the clouds, mountain under water—with another equally embodied set, as the visitor walks through, not merely observes, the scale model. Because of the enormity that they represent and the skill with which they represent it, Stillness in Motion and Water Line deliver a whole range of sensible and intelligible dimensions that relate to the immersive artistic installation. In discussing Lin’s work, curator Andrews quotes Rebecca Solnit, whose characterization of installation art also describes this strange and wonderful combination of the intelligible and the sensible: “Installation could be described as an attempt to speak the mind in the languages of the body: space, substance, systems, sensation.”10 This language of the visitor’s body finds itself responsive to language of the artist, which, according to Lévi-Strauss, locates itself “mid-way between design and anecdote.” Saraceno’s and Lin’s sculptural languages are a species of this mid-way: supported by science, they are more persuasive than anecdote; buoyed by imagination, they are less inhibited than design. They materialize what Lévi-Strauss says “unit[es] internal and external knowledge, a ‘being’ and a ‘becoming,’ [to] produc[e] an object which does not exist as such,” but which the artist “nevertheless [is] able to create.”11 Propelled through the expanse of space over the course of time, visitors experience a fusion understanding and embodiment, Solnit’s “space, substance, systems, sensation.”

Tomás Saraceno: Stillness in Motion—Cloud Cities, installation view, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, December 17, 2016–May 21, 2017. Photo: © Saul Rosenfield 2017.

Standing at one edge of Stillness in Motion, my eye almost touching a node and sighting along an elastic polyester ropes, I see in the distance a cluster of cords of different thicknesses. They form a polygonal structure that resembles a spherical manifestation of Fuller’s geodesic dome. As my eye follows the rope, my virtual body cannot resist joining in, the length of rope becoming a thoroughfare. Imagining myself small, the polygon becomes a city, the distance, maybe six feet, becomes hundreds of yards, maybe miles. The reflective surfaces contribute to my willing suspension of disbelief by abstracting and expanding the space. The sheer number of nodes stand in not only, as the label states, for “the networks of human connectivity that Saraceno envisions in the airborne cities,” but also for the complexity of such arrangements, the ways in which the most lasting tenacious traces of civilization—its architecture—are dependent upon the less tangible entanglements of human conjunction.

Saraceno’s installation invites us into this world first by making it intelligible—the city still fits within the gallery—thus revealing if not the actual sensation of what it would be like to live in the clouds, then the virtual sensation of both how cloud living might comprise an urban network and the feeling of wonder such a network might induce. Here, Saraceno approximates, rather than replicates, the experience of the cloud: we accept as floating the experience of suspension, elastic cords standing in for the science of aerostatics.12 The Stillness in Motion installation won’t convince the scientist of the plausibility of what it represents, but it does model a potential arrangement of urban areas and community connectivity. Through his miniaturizing magic, Saraceno is able to emphasize the aspects of the representation that matter most to him, and by extension to us. By “accentuat[ing] some parts and conceal[ing] others,”13 the unavoidable task Lévi-Strauss assigns to all figurative artists, Saraceno nonetheless reveals to intrepid visitors some portion of the “actual”—in this case, nonetheless, fictional—object of the Cloud City.

The interplay of the technological—the idea of the Cloud Cities and their necessity—and the phenomenological is what holds the installation together. Stillness in Motion is not like a plastic model of the solar system, in which metal rods position the sun in relation to the planets. Instead, it is like a game in which visitors have been asked to participate, not by moving things around, but by imagining. Saraceno never tells us the interval from the now to a time when conditions will require retreat, up, into a new age. Neither the physical experience of the installation nor the commentary that accompanies it offers insight into the facts of cloud life or how it would compare and contrast to my life on terra firma. In fact, unlike traditional architectural models, Stillness in Motion offers no indicators of scale, including human figures. (Will we have exceeded even our bodies by then?) The beauty of Saraceno’s installation, however, is that just as it sets the body free from the constraints of typical museum behavior, it sets the mind free to imagine Aerocenic living.14 What would it be like to live in a city like this? What will Aerocenic dwellings, and communities, resemble? Will “up” and “down” shift in meaning when everything is both above and below? None of the activities Saraceno provokes—making myself small, playing the game, imagining a future—reflects normal art museum behavior. Stillness in Motion escapes the vitrine of the architectural model, the pedestal of the sculpture, and even the gallery, slipping out the back into the playground. The security guard is watchful, but hands out no reprimands for bumping into a wire, leaning against the wall, sitting on the floor, or traversing the sculpture—under cords, over cords, and sometimes both at once.15 Saraceno elevates the visitor’s whole body to the central instrument of perception. And once the artist enlists that body, and the museum grants it this rare freedom, the mind is free also to follow. In fact, it is this reversed order—mind following body, learning following play—that creates the condition by which disbelief might be willingly suspended.

At the same time, however, Stillness in Motion provides its own counterpoint. If, at one moment, the reflective surfaces expand the space, at the next, the mirror image of myself or another person disrupts the illusion. The very act of play that the museum encourages, allowing me to use my body to imagine the Cloud City, forces me to consider the immediacy of the space and consider other questions: How do I navigate not only this non-place of the future, but also this place in the moment? Where are my feet, my shoulders? Where are the other visitors? How do I fit in here, with them? I must look up, down, and sideways, close up and distant, dodging and dancing with the dozen anchor points and wires and the dozen other visitors and their equally unpredictable movements. Thus the interplay is not only between technology and phenomenology or the future and the moment, but also between body as constructive and body as potentially destructive.

Both Saraceno’s Stillness in Motion and Lin’s Water Line impel visitors to imagine themselves in two locations at once: the space of the gallery, with its insistently physical and visual experience, and the space of immense landscapes—or airscapes in Saraceno’s case—that are beyond common human experience. In Water Line, Lin positions the viewer at the bottom of the South Atlantic Ocean, or, more precisely, beneath the bottom of the sea floor, peering up to the mountain’s apex, tiny Bouvet Island, one of the most remote landmasses in the world. In Stillness in Motion, Saraceno propels us along the connective tissues of communities that would float 20 miles above the Earth. The embodiment that Lin demands is, in a sense, comprised of isolation, breathlessness, and immobility: distant from any habitable land, immersed thousands of feet below the sea level, trapped in the earth’s crust below the ocean floor. Both Lin and Saraceno present the Earth as inaccessible—in Lin’s case, ultimately alien; in Saraceno’s, relinquished—in order to save it. This is not your great-great-great-grandparent’s connection to nature, a place of romance or beauty or even of the sublime. If Lin seeks to strengthen my sense of my humanity by connecting me to nature, Saraceno seeks to reconnect me to nature through my humanity, through his vision of interactive networks and human ingenuity. In this, Stillness in Motion seems an apt physical manifestation for the aspirations, if not always the achievements, of this technological moment: modular, interconnected, and green.

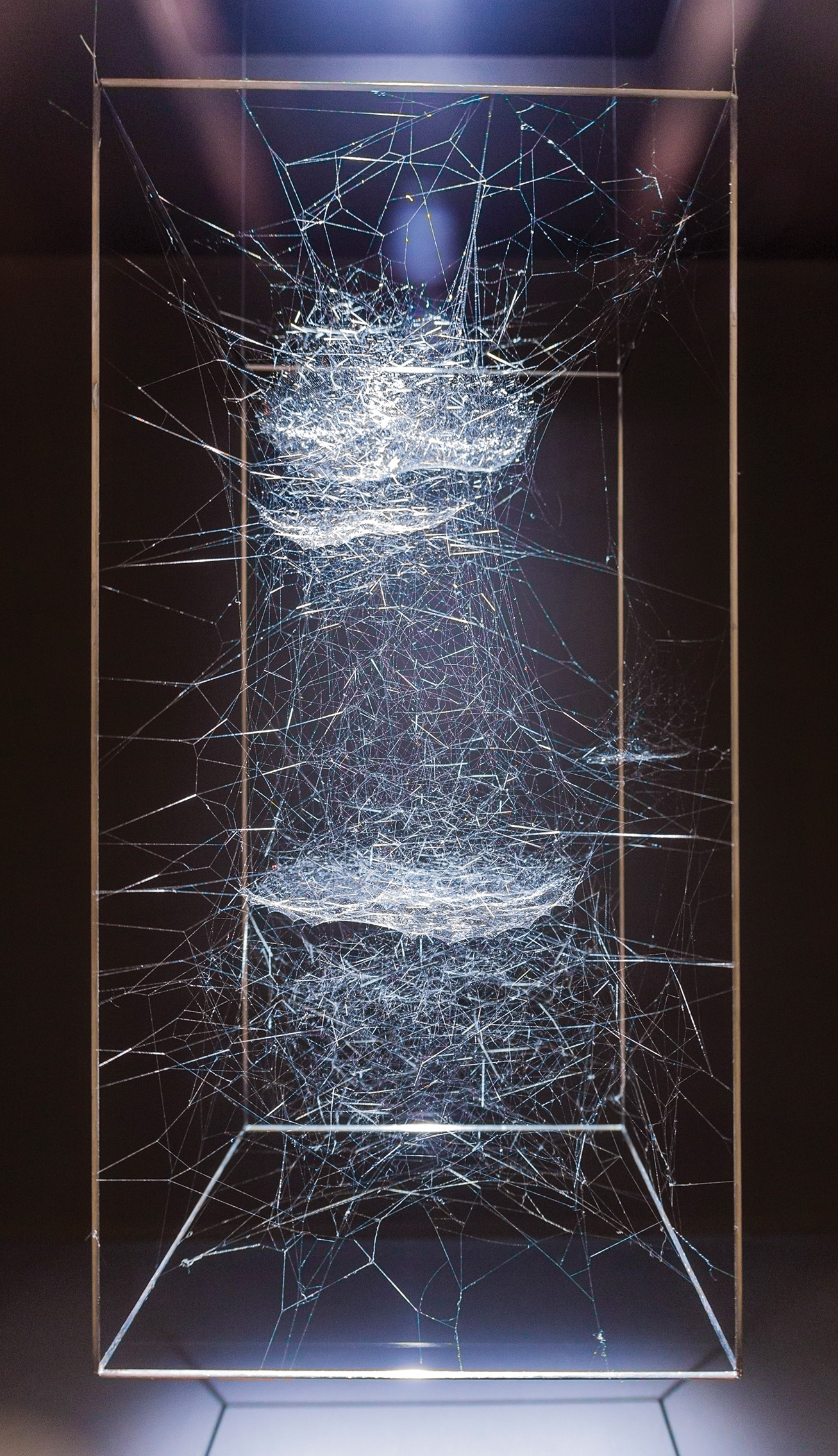

Tomás Saraceno, Hybrid Dark solitary semi-social Cluster Kepler-20b built by: a solo Linyphiidae sp.—two weeks—and a solo Cyrtophora citricola—two weeks, rotated 360°, 2016. Spider silk and carbon fiber, 15¾ × 7⅞ × 7⅞ in. Photo: © Saul Rosenfield 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

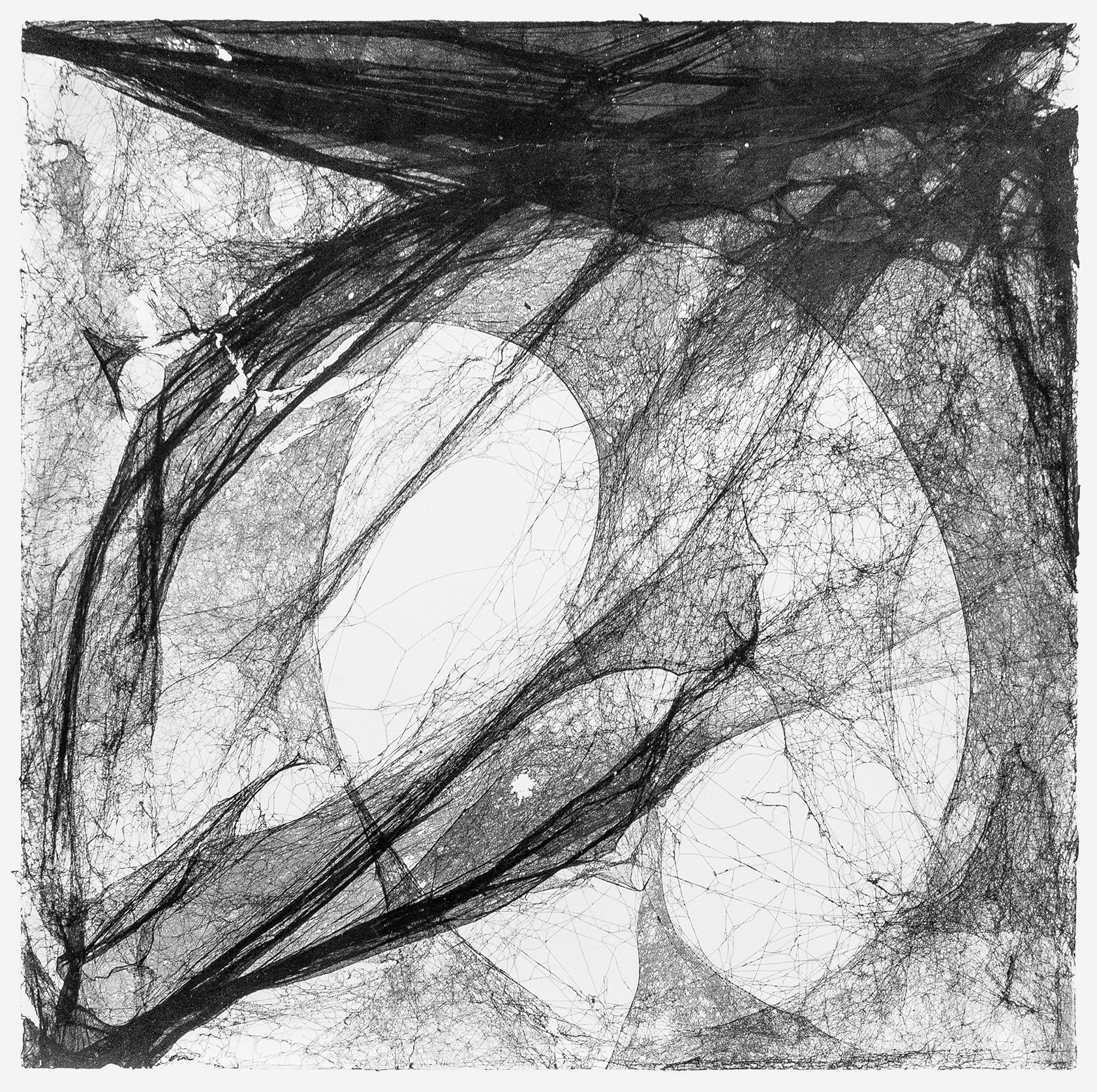

The exhibition’s two spider-generated projects visually and functionally model this concept of interconnection as well as the structure of the Cloud City. According to the wall label, the spider projects comprise “explorations of cooperation and cohabitation.” In the first project, Saraceno mounts eight drawings made of flattened spider’s webs enhanced with ink, for example, Solitary mapping of CL 1358+G2G1 by: a solo Tegenaria domestica—two weeks; the drawings evoke the galaxies for which Saraceno names them.16 In the second project, a three-dimensional work, Saraceno “collaborates” with arachnids—solo Linyphiidae and solo Cyrtophora citricola. While inhabiting a carbon fiber armature within an acrylic box for a period of residence, the spiders create a three-dimensional representation of connected space. If Saraceno’s “collaboration” with spiders does not comport with the ethics and politics of consenting human collaborators, they do frame, for the artist, the inevitable entanglements among beings as a condition of being. On his “Hybrid Webs” webpage, Saraceno quotes Dorion Sagan: “[Thus] life is not just about matter and how it immediately interacts with itself but also how that matter interacts in interconnected systems that include organisms in their separately perceiving worlds—worlds that are necessarily incomplete, even for scientists and philosophers who, like their objects of study, form only a tiny part of the giant, perhaps infinite universe they observe.”17

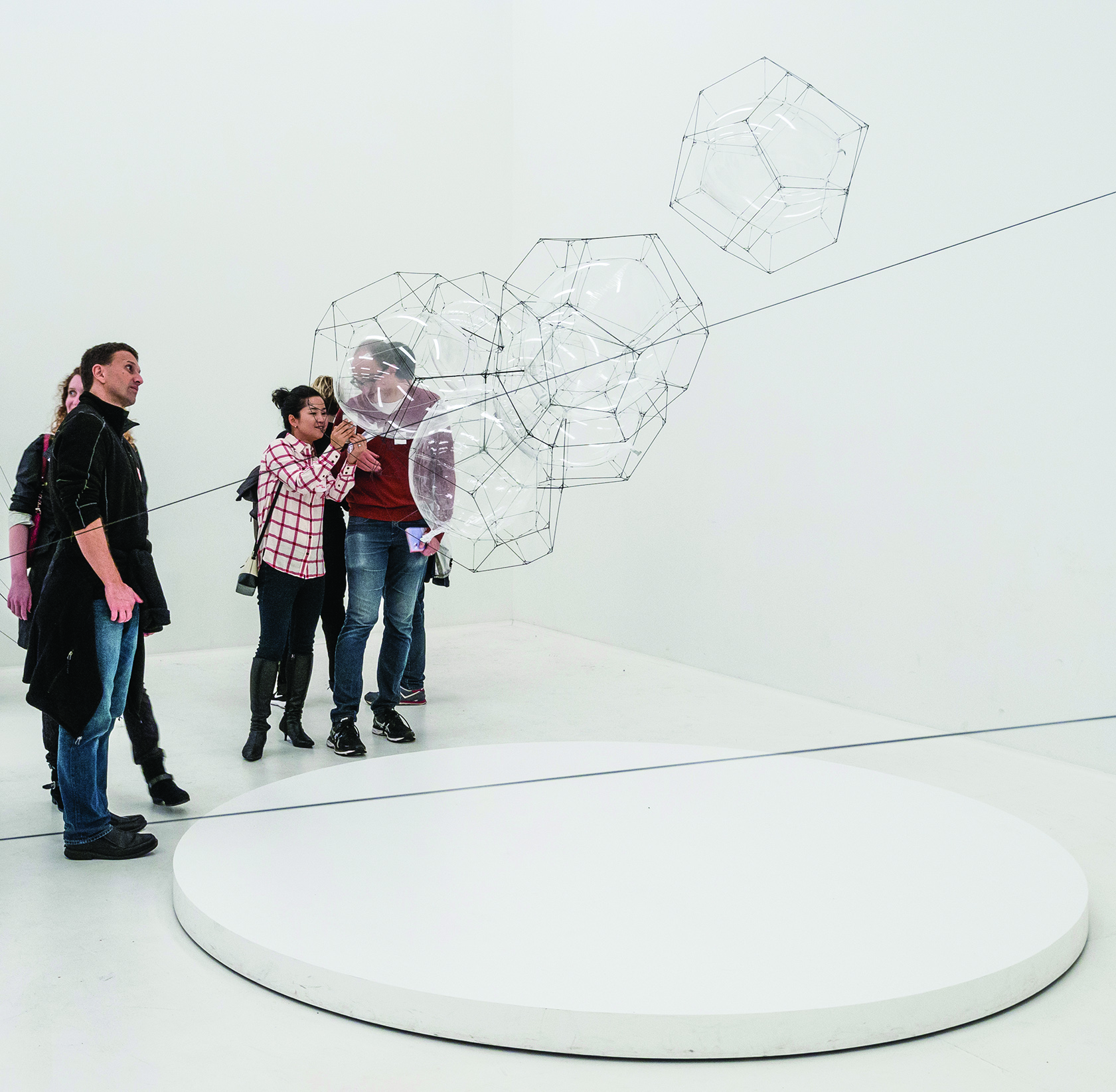

If Stillness in Motion offers a sense of the whole urban enterprise, a schematic of a world interconnected, two works from Saraceno’s Cloud Cities Thermodynamics of Self-Assembly (2015–16) series, which occupy another corner of the same gallery, display the technology that would support the airborne city. Hovering a few feet above the gallery floor, one plastic-balloon-levitated geometric structure stretches five feet across, another is about two feet wide. Tethered to the floor by barely visible filaments of polyester rope, Saraceno’s “self-assemblies” appear as magical, their buoyancy sustained, it seems, by air only a degree warmer than the atmosphere outside its bubble, in accordance with Saraceno’s (and Fuller’s) theory. But it turns out that it is filled with helium, topped off about once a week by SFMOMA staff. When, at the media preview, I expressed confusion—“helium” is absent on the work’s label—the artist smiled and characterized the artwork as a “demonstration.” The non-architect faces limitations to an intuitive understanding of architectural practice, so architects routinely create models like these not so much as working prototypes but rather as explanations of possibility, as demonstrative rather than literal, requiring a suspension of disbelief. Saraceno’s demonstration is consistent with this practice, but his label omission distinguishes his work from typical commentary at both art museums and science museums. Art museum practice would demand that the label include a complete listing of materials, in this case requiring the addition of “helium.” Although science museums do sometimes create similar sorts of demonstrations, curators would have sought a way to exhibit the actual technology, not a visual facsimile of it, for example by documenting a balloon flight based on Saraceno’s methods as does the artist’s video, Aerocene, launches White Sands (NM, United States) (2015). The omission of “helium” is part of Saraceno’s hybrid art–science-design-architecture-engineering project, the fictional hot air as the moment of untruth necessary to make his vision real enough for the moment.

Tomás Saraceno, 005, 2015 and 001 K1016c, 2016, of the Cloud Cities Thermodynamics of Self-Assembly series. Carbon fiber, plastic inflatable, glue, and polyester rope. Installation view, Tomás Saraceno: Stillness in Motion—Cloud Cities, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, December 17, 2016–May 21, 2017. Photo: © Saul Rosenfield 2016.

Art is always a theatrical process, an illusion dependent on the deflection of the viewer’s attention away from the source of the trick. The labels in the exhibition become a crucial part of that illusion; concealing the helium, omitting a description of Cloud City living, and obscuring details of scale all function to avoid foreclosing for the visitor the possibilities of Saraceno’s—and the visitor’s own—vision. The labels achieve just the sort of misdirection that is crucial to magic: they are filled with the evocative detail that studies of museum behavior suggest visitors crave, just not enough to pin down the Cloud Cities, to suture them to the skepticism engendered by radical ideas for a new epoch.

Tomás Saraceno, Solitary mapping of CL 1358+G2G1 by: a solo Tegenaria domestica—two weeks, 2016. Spider silk, ink, and fixative on paper, 1615⁄16 × 615⁄16 × 115⁄16 in. Photo: © Saul Rosenfield 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

Cenozoic Living

At this moment of environmental reckoning, what can art contribute? It can seek to document the tremendous changes wrought by Anthropocenic activity, as do photographer and filmmaker Edward Burtynsky and his collaborator Jennifer Baichwal.18 It can tally and map Anthropocenic extinctions, as Maya Lin does in her ongoing multi-platform memorial project, What Is Missing?, whose “global Map of Memory showcases historical, factual, and personal accounts of what we have lost from the natural world.”19 Art can also render Anthropocenic dystopias as these futures verge toward anthropo-absence. Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road, which is evocative enough to comprise a work of visual art, tracks the wanderings of an unnamed father and son, victims of an unspecified apocalyptic event that has left the landscape uninhabitable and its other inhabitants dangerous.20 The novel tenderly portrays the survival of compassion and love without descending into a saccharine or untruthful evasion of the catastrophe it depicts. All three interventions force us, today, to imagine a future beyond our comprehension, when geochronological strata will reveal the devastation that humans will have wrought on ourselves.

Or art can invoke the Anthropocene by envisioning a new epoch, the simple act of imagining beyond our time forcing the art participant into a radical recasting of perspective, looking forward to see backward to this contemporary moment. Saraceno frames his symbiotic Cloud Cities as places we could inhabit in an attempt to save the planet from ourselves before it is too late. In his vision of the clean, buoyant Aerocene, humanity embraces a fossil-fuel-free future now, and the Earth survives intact. But, the history of sci-fi is littered with Cloud-City-like habitations that have risen in the wake of an irrevocably spoiled Earth, last-ditch alternatives to the toxic, sunken Anthropocene. In this sense, Stillness in Motion double-punches us with two contradictory futures, both of which might enlist the Cloud City: one, a hopeful and beautiful image of a sustainable Aerocenic future that reclaims the Anthropocene; and the other, the dystopian vision of irrevocably toxified Anthropocenic one, in which the Cloud Cities become last resorts, spaceships to raise us above the uninhabitable earth. But, and here’s the kicker, no matter which epoch you imagine—Saraceno’s Cloud Cities protect the fragile Earth from the people, or Saraceno’s Cloud Cities protect the people from the toxified Earth—you find yourself ungrounded, unEarthed. Or, more precisely, you find yourself grounded in loss, a lost terrestriality.

Saraceno believes in his vision. And it is a vision worth pursuing. It might be, in the end, that the job of art is to use any means—utopian or dystopian—to bring us to this precipice of truth in order to impel us to step backward.

Tomás Saraceno, Aerocene, launches in White Sands (NM, United States), 2015. Photo: © Studio Tomás Saraceno.

Rob Marks writes about art and aesthetic philosophy. He publishes in Daily Serving, Art Practical, Frieze, and X-TRA. He has written extensively on the nature of the museum and on the work of Richard Serra. His chapter “In the Body’s Space, the Body’s Time: Feeling Your Way Through Richard Serra’s The Matter of Time,” is forthcoming in Sarah Lippert’s Space and Time in Artistic Practice and Aesthetics (I.B. Tauris).