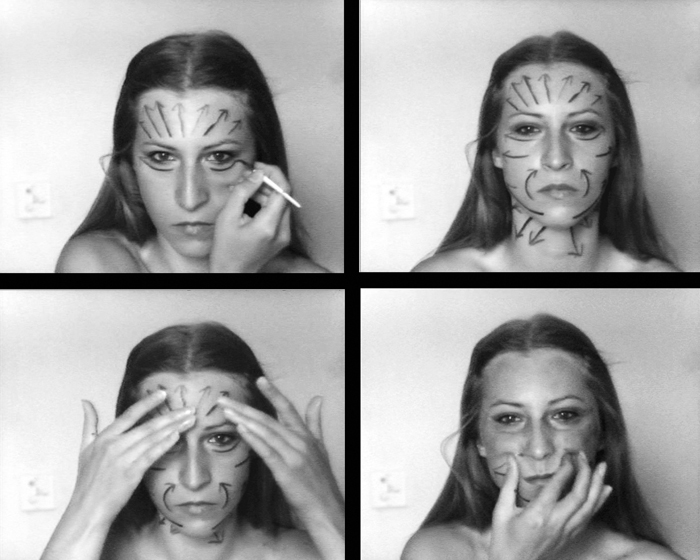

Sanja Ivekovic ́, Instructions No. 1, 1976. Video (black and white, sound), 5:59 min. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift Of Jerry I. Speyer And Katherine G. Farley, Anna Marie And Robert F. Shapiro, Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis, and Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds. © 2011 Sanja Ivekovic ́.

“Once upon a time, there was a country called Yugoslavia,” wrote British historian Timothy Garton Ash in his 2001 book History of the Present: Essays, Sketches, and Dispatches from Europe in the 1990s. In her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Sweet Violence, the Croatian artist Sanja Ivekovic takes a critical perspective on her home country’s violent undoing.1The exhibition features nearly forty years of work by the artist, each project rooted in critical resistance to Yugoslavia’s politically agitated condition. Over and over, Ivekovic considers the pernicious intersections of collective history and private desire, and of consumerism and violence, by adroitly using the instrument of the state—mass media—as her medium of choice. Considered the first feminist artist from her region, Sweet Violence proves Ivekovic to be an incredulous and unshrinking critic. She could slit your throat before you even noticed the blade.

Ivekovic was born and continues to live in Zagreb, Croatia, and its complex history courses insistently through her work. Ivekovic was born in 1949, just four years after Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin signed the Yalta agreement, which granted Soviet control over Eastern Europe at the end of World War II. Soon after, Yugoslavia became the first nation to successfully reject Soviet hegemony under Josip Broz Tito. Ivekovic grew up during the resulting “Yugoslavian experiment,” which lasted until the dictator’s death in May of 1980. Yugoslavia existed as a profound paradox: a socialist country outside the Soviet sphere that was still technically situated behind the Iron Curtain, forging diplomatic and trade relationships with Western Europe, even making overtures to the United States for weapons and military support. (Yugoslav art historian Bojana Pejic wrote of the period: “Marxism and Leninism in schools matched with sex drugs and rock and roll.”2) In the wake of Tito’s death, and the uncertain aftermath of a lengthy dictatorship, Yugoslavia, which had been made up of six republics—Bosnia, Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia—became unhinged, violent, and fragmented under the stress of rising ethnic nationalism.3 The resulting conflicts are too intricate to describe in adequate detail here, but by the fall of the USSR in December of 1991, 250,000 people had been killed by war and “ethnic cleansings” between the republics. This is not even to speak of the bloodlettings in Bosnia and Kosovo over the course of the 1990s. The history of Yugoslavia in the past century, which philosopher Terry Eagleton states “cannot be spoken of without blistering the tongue,”4 is Ivekovic’s volatile inheritance.

Zagreb’s history is impossible to distill from Ivekovic’s practice, yet, aside from a paragraph at the entrance of the exhibition, wall didactics are conspicuously absent at MoMA. Interestingly, the most extensive reference material may be found on the floor: crumpled up red leaflets are scattered unevenly in every room of the exhibition. When unfurled, one finds Shadow Report (1998), a two page, double-sided treaty that lists facts about femicide and international abuses of women’s rights. The literature is based on Amnesty International’s communiqué, Treaty for the Rights of Women. The treaty, which was adopted by the United Nations in 1979 but remains unendorsed by the United States, lies rejected at our feet.

A large exhibition, Sweet Violence follows a loosely chronological framework. The galleries are full, but not overly so, and weave fluidly between collage, video, drawing, installation, and photography. Near the entrance of the exhibition sits Instructions No. 1 (1979), a video playing on a small, wall-mounted monitor that depicts Ivekovic at age twenty-seven, her heart-shaped face just smaller than life size. Never diverting her dull gaze from the camera, as if it were her vanity mirror, she paints thin arrows of black ink across her forehead and under her eyes, and traces the shallow creases around her mouth and jaw. The marks at once suggest war paint, a cosmetic surgery plan, weather patterns, skin care directions, and a map to nowhere. After spending most of the almost six-minute video systematically covering her face, the artist hurriedly massages the marks in. The overlay is disappeared, but faint traces remain, blotted out and blotted in.

An adjacent gallery houses Ivekovic’s most well-known series, Double Life (1975–76), which is the grounding force of the show. The project was made during a productive period for Ivekovic, toward the end of Tito’s reign. Yugoslavia was not only lodged between a one-party system and consumerist impulses, but also between the promise of socialist egalitarianism and the reality of dogged patriarchy. Feminism did not exist, or, as Pejic has written, was considered entirely “superfluous to a communist society which had already ‘overcome’ gender differences in the revolution.”5

In each of the sixty-four diptychs that make up Double Life, a photograph of the artist (nearly all black and white), taken between 1953 and 1976 and culled from her own family albums, is paired with a print advertisement from publications such as Elle, Marie Claire, Amica, and Anna Bella. Unlike other countries behind the Iron Curtain, such as Bulgaria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and the USSR, Yugoslav women had access to Western clothing trends and popular magazines. The image pairs are matched on the basis of corresponding gestures: A brunette model covers her face with her right hand while her hair blows in the wind; so does Ivekovic. A blonde model emerges smiling from the ocean in a graphic bikini, waving to someone just outside of frame; so too does Ivekovic. Each diptych is labeled according to the corresponding dates and locations, revealing that Ivekovic’s personal images are not mimicries. Instead, most of Ivekovic’s snapshots predate their companion advertisements, creating a retroactive doubling or uncanny déjà vu. This reversal of expectation is pivotal to the work, and also distinguishes her project from Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills (1977–80), which were to come the following year. Ivekovic’s series speak to a dilemma similar to Sherman’s, though in this case it’s a two-sided mirror: Double Life probes how women become absorbed by a culture that, in fact, feeds off of them. Curator Roxana Marcoci explains in her catalog essay: “Unlike [Cindy] Sherman…Ivekovic is not masquerading in different roles, but exploring her own life as a series of roles retroactively assigned.”6 Double Life probes not only the manner in which women played a distinct role in creating their own social conditions but also the schizophrenic effect of consumerist impulses on a socialist country.

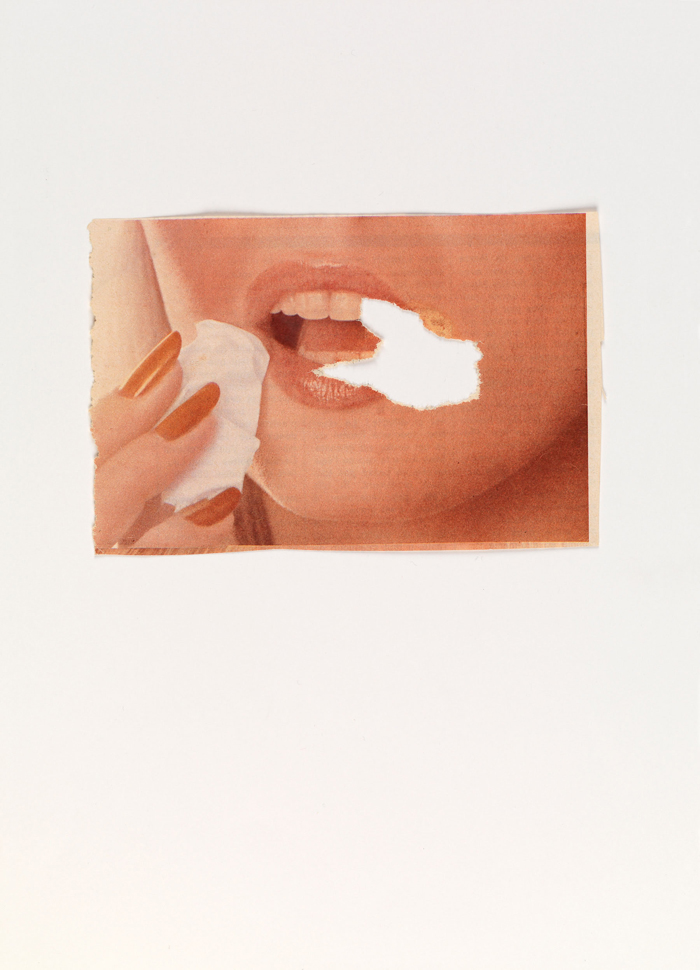

As the decade wore on, Ivekovic took to treating advertisements more violently, her tight smile shifting to a pitched scream. In Paper Women (1976–77), Ivekovic treats the veneer of advertisements directly, administering a series of small cuts and rips to eleven print photographs of women’s faces and necks. The scratches on Paper Women are so delicate that they often don’t go through the thin paper; Ivekovic lacerates her victims with the singular care of a tender sadist. It is no fluke that the subjects feel muted: Ivekovic literally tears out their larynges and pins their mouths shut.7

Sanja Ivekovic ́, Paper Women, 1976–77. Collage on magazine page, 11 15/16 x 8 9/16 inches. Macba Collection, Fundació Museu D’art Contemporani De Barcelona. © 2011 Sanja Ivekovic ́.

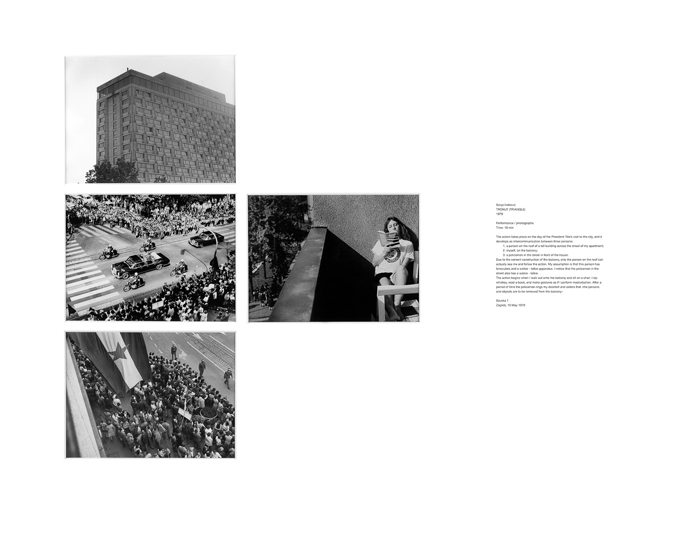

Sanja Ivekovic ́, Triangle, 1979. Four gelatin silver prints with printed text, each print 12 x 15 7/8 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York., Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds. © 2011 Sanja Ivekovic ́.

Ivekovic’s Triangle(1979)is the last piece in the exhibition that was made during Tito’s regime. A performance and video, it is represented at MoMA by four photographs. For the original work, Ivekovic simulated masturbation while seated on her apartment balcony during a parade taking place on the street below in honor of Tito, who was on a government visit to Zagreb. Ivekovic staged the performance as an affront to the state militia, whom she assumed were surveilling her building during the festivity, as it was on the official parade route. Ivekovic anticipated correctly: Though seated in a low chair, out of view of the crowded public spectacle, after eighteen minutes, she received a threatening knock on her door. The secret police ordered, “The persons and objects are to be removed from the balcony.” The performance exposed the masculinized regime under which discrete and private bodies—notably women’s bodies and their expressions of sexual desire—were monitored and controlled as part of the state apparatus.

By this time, Ivekovic had moved on from appropriated print advertising strategies to working in video, performance, and photography, though her interest in dissecting mass media as a weapon of veiled ideological power persisted. Into her videos she intercut clips from news television programming, as in Personal Cuts (1982), and from soap operas, as in General Alert (Soap Opera) (1995). In the latter video, Ivekovic replays an episode of a popular Spanish soap opera (broadcast with Croatian subtitles) that she taped during an air raid scare in Zagreb. Periodically, above scenes of Spanish soap actresses theatrically crying and embracing one another, “GENERAL ALERT ZAGREB” flashes in yellow letters. In the short video, as with the best of Ivekovic’s work, private melodrama and collective tragedy bleed into one another through a fine media filter.

The most recent piece in the show is housed in MoMA’s atrium, the only site inside the museum that is tall enough to hold Ivekovic’s enormous Lady Rosa of Luxembourg (2001). Though it is on a lower floor, a museum guard informs passing MoMA visitors that the monument is intended to be viewed as the final measure of the exhibition. A replica of a war memorial featuring a neoclassical Nike, Greek goddess of victory, Ivekovic’s version was initially installed one hundred meters from the original in the town square of Luxembourg. Nearly identical, the monuments differed in a few critical ways: although both represent a female form draped in a thin golden robe with her arms out-stretched, Ivekovic’s version is visibly pregnant, and her name has been changed in honor of the Marxist activist and philosopher Rosa Luxemburg, who was executed in Berlin for her radicalism, in 1919. Though impressively ambitious, the sculpture is disappointingly instructional. Instead of opening up the latitude for viewers to project their own questions of desire or exploitation, the piece offers up all of its own answers. The original’s carved plaque honoring male heroism was replaced with Ivekovic’s allegory for women lacking political voice and historical agency: “WHORE, BITCH, MADONNA, VIRGIN.” The most interesting thing about Lady Rosa of Luxembourg was the mass media response and public outcry to its erection in Luxembourg. In the installation at MoMA, two monitors show consecutive loops of TV commentators on the subject. Nearly one hundred newspaper articles documenting the controversy—most of them featuring front page, color images— encircle the statue in a continuous, waist-high vitrine. Though she has moved gradually away from the method over the last four decades, Ivekovic is at her most trenchant when using the media to play itself.

Sanja Ivekovic ́, Lady Rosa of Luxembourg, 2001. Installation with gilded polyester, wood, and printed and video archival material; figure: 94 1/2 x 63 x 35 7/16 inches. © 2011 Sanja Ivekovic ́.

Carmen Winant is an artist and writer living in Brooklyn, New York.