The exhibition Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art invites the kind of argumentation that political art seems to inspire, including the urge to parse out the terms of discussion. I overheard and read quite a few of these types of responses, including those from viewers who asked, what makes the works presented—and the show itself—radical? Presence of what kind? Blackness on a continuum of racial (and racialized) existence, or as an absolute? And even, is this Art? (Yes, performative practices still find themselves defending their legitimacy.) The artists in the show are black, and they perform in a medium—“black” human bodies—whose existence has been objectified, commodified, and repressed for as long as the United States has existed, indeed, whose subjection is the physical and psychic bedrock of this country’s founding and its current state. This work is both political and politicized.

This tendency toward argumentation on the part of viewers is, of course, defensive and preemptory. Fixing the terms in place before addressing the work itself and attempting to “know what you’re dealing with” before engaging are tactics aimed at avoiding the discomfort of listening to unfamiliar or painful truths. Difference, one’s own limits and limitations, one’s own privileges (or lack thereof), and one’s own accidental or purposeful overstepping of legitimate power or boundary conditions are part of what one confronts when engaging with another person’s political statement.

Perhaps my name suggests to you that I’m a white person; it’s true as far as I know, and regardless I’ve lived as one. While I have long followed and engaged in performance myself, visiting Radical Presence was like dropping in on the middle of a conversation and realizing that it has already been happening for a long time. I found myself wanting to return to this exhibition again and again, compelled by what I had experienced.

Clifford Owens, Anthology (Nsenga Knight) (detail), 2011. Two C-prints, 40 × 60 inches each. Courtesy the artist.

Radical Presence developed out of collaborative research undertaken by the show’s curator, Valerie Cassel Oliver (senior curator at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston) and the artist Clifford Owens.1 Over the course of several years, they amassed a provisional history of avant-garde black performance—a collection of art and artists whose stories, they realized, had not yet been aggregated, much less coherently told. When their initial book proposal foundered on funding difficulties, they took their research in several directions. Cassel Oliver curated a 2010 retrospective of artist Benjamin Patterson’s work2 and from there developed Radical Presence, first exhibited at CAMH in 2012. Owens created work in collaboration with many of the show’s artists for his show Anthology, a series of live performances at MoMA PS1, in 2011–12; several documented selections from this project are included in Radical Presence.3

Most reviews I’ve read indicate that this show is broadly appreciated and quite successful. It accomplishes what many exhibitions can only hope for: it is essential. But others have argued that Radical Presence is, instead, essentializing, and therefore problematic, for focusing on blackness as a category4 and for not more clearly defining what it means by “radical.”5 In the wake of the Eric Garner decision (among other recent occurrences), some have questioned whether any artwork installed in what they see as an “elitist, white-cube institution” can be radical at all.6 There is also a potential problem—or at least an irony—in naming a show about performance “presence” when, for the majority of its hours of operation, it confronts viewers with the absence of any live human body performing.7

This exhibition presents work by close to forty American and Caribbean artists that belongs in any discussion of performance art as a form. Though performance has only emerged as an institutionally anointed art form in recent decades, we should question why we didn’t know about much of this work sooner. For example, last winter, when I saw the Whitney Museum’s Rituals of Rented Island—an exhibition largely devoted to unknown and “radical” performance art in Manhattan in the 1970s—I was surprised by how few of its artists overlapped with Radical Presence (which was on view concurrently at The Studio Museum in Harlem and at Grey Art Gallery at New York University). Radical Presence is essential because it introduces new truths into the realm of the contagiously knowable—narratives and stories and pictures and retellings that we might now pass on to one another. It does what scholarship should do, attempting to indicate the wholeness of the field, even as wholeness is always an unachievable goal.

Cassel Oliver’s and Owens’s initial research into black artists’ performative strategies within the visual arts led them to Benjamin Patterson, a founding member of Fluxus whose oeuvre had not yet received much critical attention. In Patterson’s early formal and structural experiments, he combined an avant-garde music practice with text works, time-based visual arts happenings, and audience participation, strategies that animate his practice to this day.8 From this de facto patriarch (at age 80 he’s the show’s eldest contributor), a loose but thoroughgoing conversation could be traced between multiple generations of artists working in homage to and branching off of one another’s practices.9 In opening-weekend remarks, Cassel Oliver discussed how the show’s apparent “genealogical imperative” has long been actualized and lived out within the many mentor-student relationships between older and younger artists in the show, illustrating how personal art history can be when the “call-and-response” transfer of ideas is nurtured through friendships and affinities.10

Evidence of this cross-fertilization animates the exhibition. Scattered throughout are multiple works from Clifford Owens’s Anthology series (2010–12), for which he asked over twenty influential black artists to write performance scores for him to interpret and enact during his ten-month residency at PS1. Photo documentation and, in one case, a sound recording of the resulting performances are displayed. In the photos, Owens is usually alone, wearing a black dress shirt and pants, often engaged in inscrutable, inspired mess making. At the instruction of Nsenga Knight, we see him tossing white powder above his head and letting it settle onto him and what looks like an otherwise tidy parquet-floored office. For Senga Nengudi, he slices open bags of vivid pigment to spread across what looks like an attic floor. Glenn Ligon asked him to re-perform David Hammons’s Pissed Off (1981), so he pisses on what looks to be either a floor-bound, minimalist steel sculpture or an open drain. Elsewhere, you see Owens interacting with a public: Kara Walker’s score, intended to engage Owens’s own as well as his audience’s ethical and erotic boundaries, required him to French kiss strangers and both demand and refuse sex.11 In five documentary photos, there he is, mid-grope (all above-neck), engaging a series of apparently game recipients of his advances in a room of onlookers.12 Although in each of these gambits Owens plays the starring role and interprets the scores freely, he has at the same time ceded his body to other artists’ interests.13

Derrick Adams, Communicating with Shadows: I Crush a Lot (number 4)[Hammons], 2011. Digital print, 35 3⁄4 × 24 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Actual homages reveal themselves in other inter-show conversational threads. Derrick Adams’s Communicating with Shadows: I Crush a Lot (numbers 1–4) [Hammons] (2011) and Adam Pendleton’s video Lorraine O’Grady: A Portrait (2012) directly address the subjects of their admiration. Photographs document Adams’s improvised performance involving props of block ice, a cooler, and other related elements in front of a giant, projected silhouette of Hammons as he was dressed on the day of his own now-iconic performance Bliz-aard Ball Sale (1983). In the Walker exhibition, the slideshow of Hammons’s performance was on view just steps away. For Lorraine O’Grady: A Portrait, Pendleton spliced footage of interviews he had conducted with O’Grady, arguably the show’s grand dame, to bend and repeat elements of her narration, the nonlinear editing emphasizing the uniqueness of her life story, her perspective, and her artistic accomplishments. In Another Kind of Love: John Cage’s “Silence,” By Hand (2013–14), Pope.L hand-copied an entire book by Cage, another of the show’s spiritual forefathers, and adhered each page to the wall in an expansive, minimalist grid. Nearby was Patterson’s Pond (1962): a grid of vinyl tape applied to the floor, where several wind-up toy frogs might be sitting, ready to be “played” by occasional participants according to the original score, hanging adjacent. The oldest work in the show, Pond embodied a muted reminder of the spirit of playful reinvention that engendered so much experimentation by so many artists thereafter.

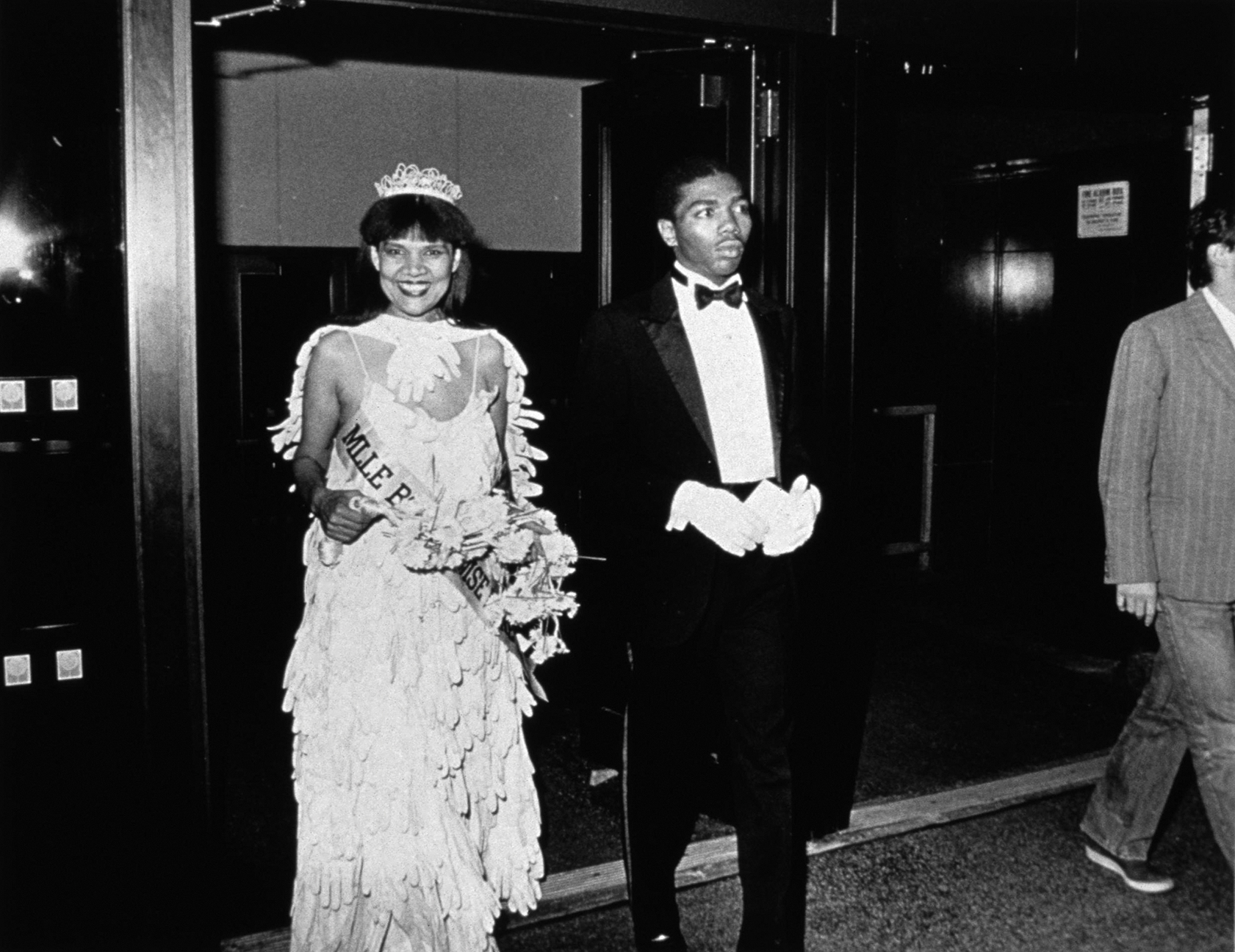

But as evident as this sense of celebratory, intergenerational improvisation and respects-paying was, I was struck by an even more obvious influence on the work of these artists—that of the larger context in which the work is created, and in which we live, a context rarely so life-affirming.14 Many artists chose to embody a history of oppression and trauma as an act of protest and strategy of resistance—and often as a way of standing and fighting for other causes. Lorraine O’Grady crashed several New York art openings in the early 1980s in the guise of Mademoiselle Bourgeoise Noire, dressed in a gown she’d sewn together from 180 pairs of white thrift-store evening gloves, a sash emblazoned with her persona’s moniker, and a tiara. She carried, in lieu of a bouquet, a cat-o’-nine-tails made from rope and white chrysanthemums, and began her performances by whipping her own back 100 times in the midst of the crowd. Upon ceasing, she yelled out poems written for each occasion that called out the timidity of black artists’ engagement with the (predominantly white) art world.15 The documentary photos of these acts depict a defiantly spirited enactment: Mlle Noire/O’Grady smiles in nearly every shot. Tameka Norris has several times performed Untitled (2012), which is documented in a video presented along with her costume, an orange jumpsuit. In this performance, Norris enters a gallery, makes eye contact with each viewer, silently slices her tongue with a knife, and then traces the room’s periphery with her mouth, sucking a lemon to keep the wound open, encircling the room with this “painting” in lines as straight as she can make. The lines drip, of course.16

Benjamin Patterson (seated, center) with Walker Art Center Teen Arts Council performing Pond (1962) at the Walker Art Center, October 9, 2014. Courtesy Walker Art Center.

Lorraine O’Grady, Untitled (Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and her Master of Ceremonies enter the New Museum), 1980–83, printed 2009. Gelatin silver print, 7 1⁄4 × 9 1/5 inches. Courtesy the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

Lorraine O’Grady, Untitled (Mlle Bourgeoise Noire beats herself with the whip-that-made-plantations- move), 1980–83, printed 2009. Gelatin silver print, 9 3/5 × 7 1/3 inches. Courtesy the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

Other risky interventionist practices represented in this show take place outside, in the world, on the street. Dread Scott walked around Harlem, well dressed in a suit and hat, wearing a sign the length of his torso that said simply, “I AM NOT A MAN.” The text rewrote the poster made famous during the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike of 1968, which read, “I AM A MAN.” The resulting performance stills show public reactions to him that appear by turns curious, perplexed, knowing, appreciative, offended, concerned, or willfully ignorant of his embodied politics, a politics that questions how much progress has been made since 1968. Papo Colo’s practice has long involved physical endurance, risk, and exhaustion to prove a political point. For Superman 51 (1977), to protest the rejection of Puerto Rico as the fifty-first United State, Colo ran the length of the West Side Highway in New York City multiple times, dragging lumber and sticks tied to his body, running to the point of exhaustion.17 The sight of his body, alone and encumbered, sculpturally Sisyphean, elicits a complex, humored, horrified remorse: he may be clowning to the point of death.

Rather than pathologize “self-harm,” these artists’ actions incorporate it into a vocabulary of purposeful risk-taking; this is institutional and social critique made corporeal. Difficult as it may be to witness or hear told, the narrative strategy of violence turning inward in order to turn outward has long been practiced in performance art, performing degradation, abjection, and “endurance.” But the significance here lies in doing so not because you can, in the way that an artist like Chris Burden made an early career of, as both Cassel Oliver and curator Paul Schimmel before her have pointed out,18 but because of what you and yours have had to endure. The controlled reprise of these works transmogrifies the horror into something instrumental.

When people intentionally do strange things with their bodies in public, I become appreciative, even elated, especially when there’s something obviously difficult about the act. Difficult in relation to the physical surroundings, to surrounding people. Difficult in relation to rules and social codes. Difficult in relation to bodily capacity, either normative or particular to an individual. From the virtuosic parkour of impromptu acrobatic pole routines on the J-train to bodies lying down in protest before militarized police, these live acts enliven me as a witness. I participate internally; my body, in time, follows. In all of these disruptive, insubordinate, sometimes confrontational symbolic acts, the artists become something more than human—a role, a metaphor, an idea in costume. They also remain all too human, vulnerable despite their flamboyant disregard for security.

Tameka Norris performing Untitled (2012) at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, November 17, 2012. Photo: Max Fields. Courtesy Contemporary Art Museum Houston.

Performance art is comprehensible on many levels—emotional, physical, sensory, intellectual, historical. Seeing images in Radical Presence of bodies putting themselves at risk—especially in a country where white violence against black and brown bodies is still regularly rendered with impunity—I feel the impact of their invitations to consider and to respond all the more deeply. The ethical place holding established by each of these pieces gives us space to imagine a different outcome. The work offered up in the exhibition, even as documentation, affects me with its fearlessness in response to problems and inequities. In nearly every piece, we see a rule bent or broken, a code of conduct dismissed, a protocol undermined, a new game proposed, a warping of the social dynamic. Their tricksters’ boldness moves the needle.

Much of the work is intentionally provocative, satirically appropriating racist language, imagery, and stereotypes to address the lived experience of prejudice. Using absurdity as a weapon, it simultaneously enacts a comic send-up of racist “logic.” In Shaun El C. Leonardo’s performance series El Conquistador vs. The Invisible Man (2005–7), documented as a mash-up music video, the artist reinvents himself as a Mexican wrestler who fights an opponent no one can see. He struts, beats his chest, and throws himself violently to the mat, raging and rejoicing in a virtuosic comedy that, despite or in concert with its entertainment value, unsettles itself (and us) by not only referencing Ralph Ellison’s novel about internalized racism but also allegorizing the genocidal practices impressed upon his Dominican ancestors to “cleanse” themselves of their black heritage.19

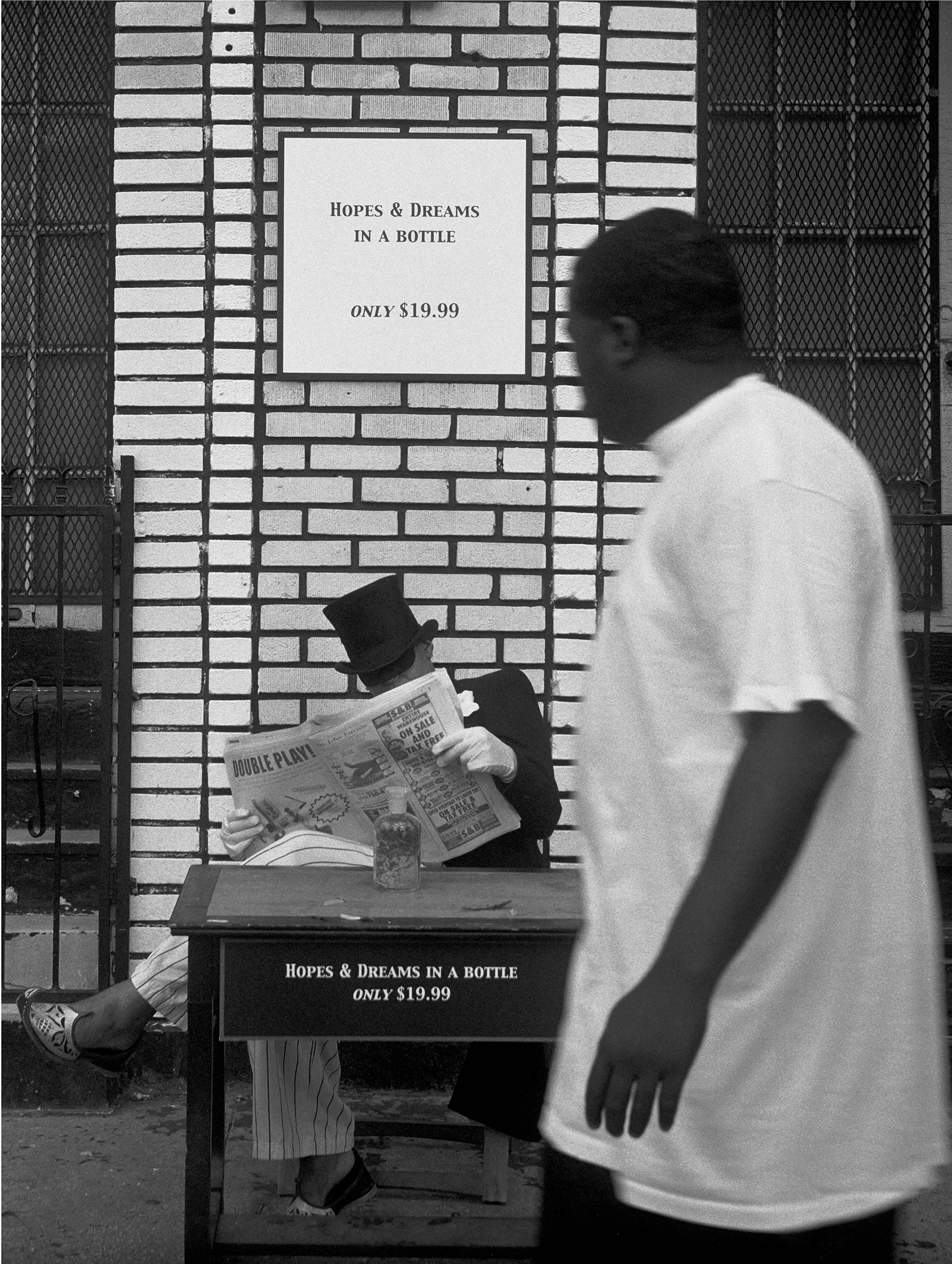

In her Hopes and Dreams series of staged interventions (2006–07), Carrie Mae Weems inhabits minstrel history in a top hat, tails, white gloves, and black mask around her eyes—a cross between Uncle Sam and a throw-back stage performer—and takes to the streets of New York. The acts are shown as a series of black-and-white photos. In one, Weems sits on a sidewalk draped in a chair, her legs crossed, casually reading a tabloid behind a small desk; two signs, one on the desk and one hanging above her, read: “Hopes & Dreams in a Bottle, Only $19.99.” A man passes in the foreground; his response is illegible, and hers mute, but the single glass bottle sitting on the desk, an apparently empty apothecary’s remnant, stands in for centuries of snake oil.

Carrie Mae Weems, Selling Hopes and Dreams, 2006–7. Digital print from black-and-white film on archival paper, 30 × 24 inches. Courtesy the artist.

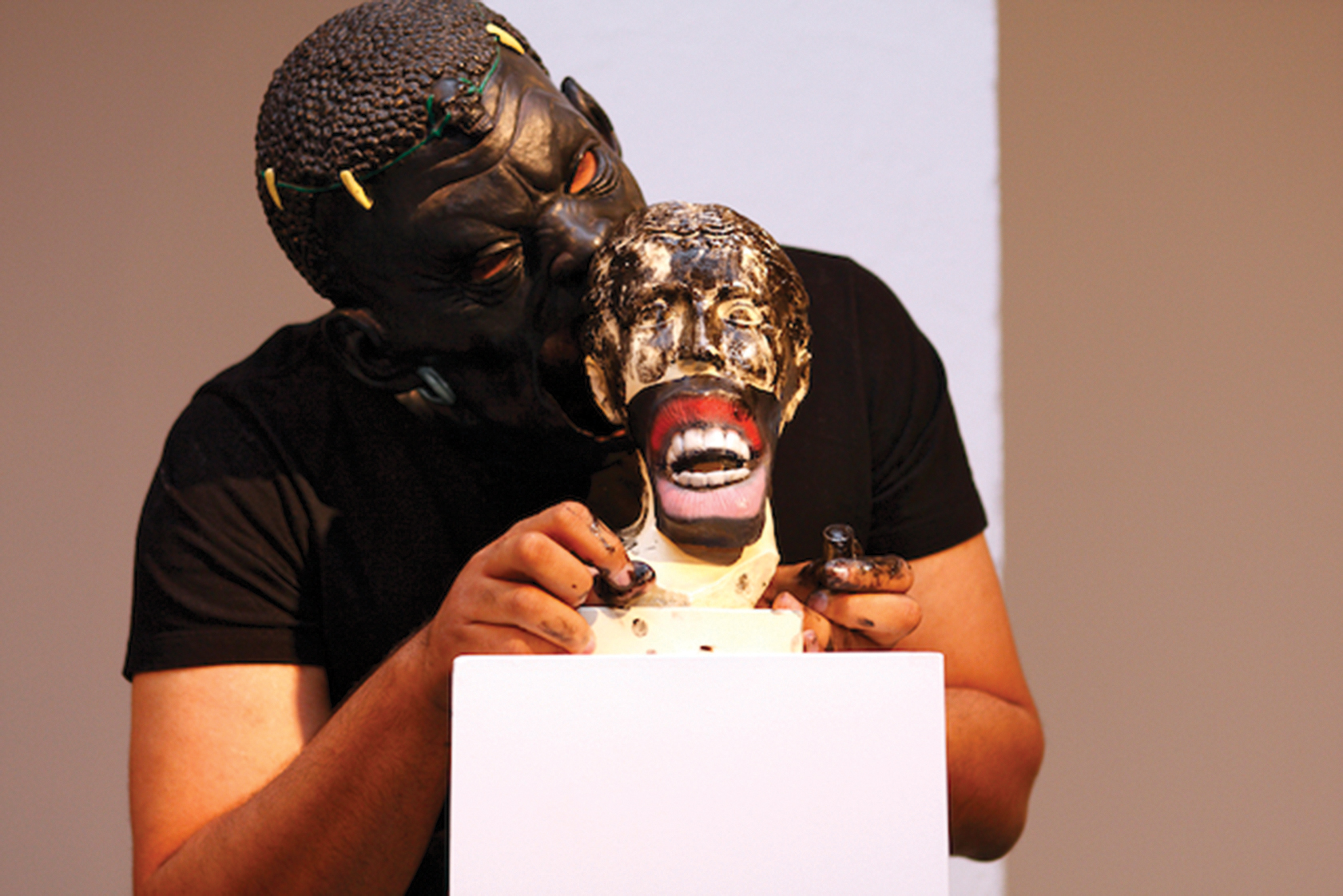

Wayne Hodge, Negerkuss (detail), 2011. Six digital photographs, 16 × 20 inches each. Photo: Kathrin Heller. Courtesy the artist.

Other “holy shit” moments in Radical Presence include those brought to us by Wayne Hodge and, perhaps most strikingly, Pope.L. In Negerkuss (2011), originally performed in Berlin, Hodge dons a full-head latex mask of a black “savage.”20 The mask’s garish mouth has been excised and strapped to a plaster copy of the Bust of Cleopatra (35 BCE) in the collection of that city’s Altes Museum. From the photos documenting the act, one sees him kiss away the whiteness, transferring black paint from his lips to this figurine until its surface shines as dark as the mask. In Europe, negerkuss (“negro’s kiss” in German) remains the colloquial name for a popular chocolate-covered marshmallow confection that is still frequently decorated “traditionally, ” i.e., anthropomorphically in blackface. Hodge’s rejoinder to this phenomenon, heavy with cultural referents, neatly and arrestingly rides the line between “historical” fears of anthropophagy and miscegenation and troubles the notion that “those days are behind us.”

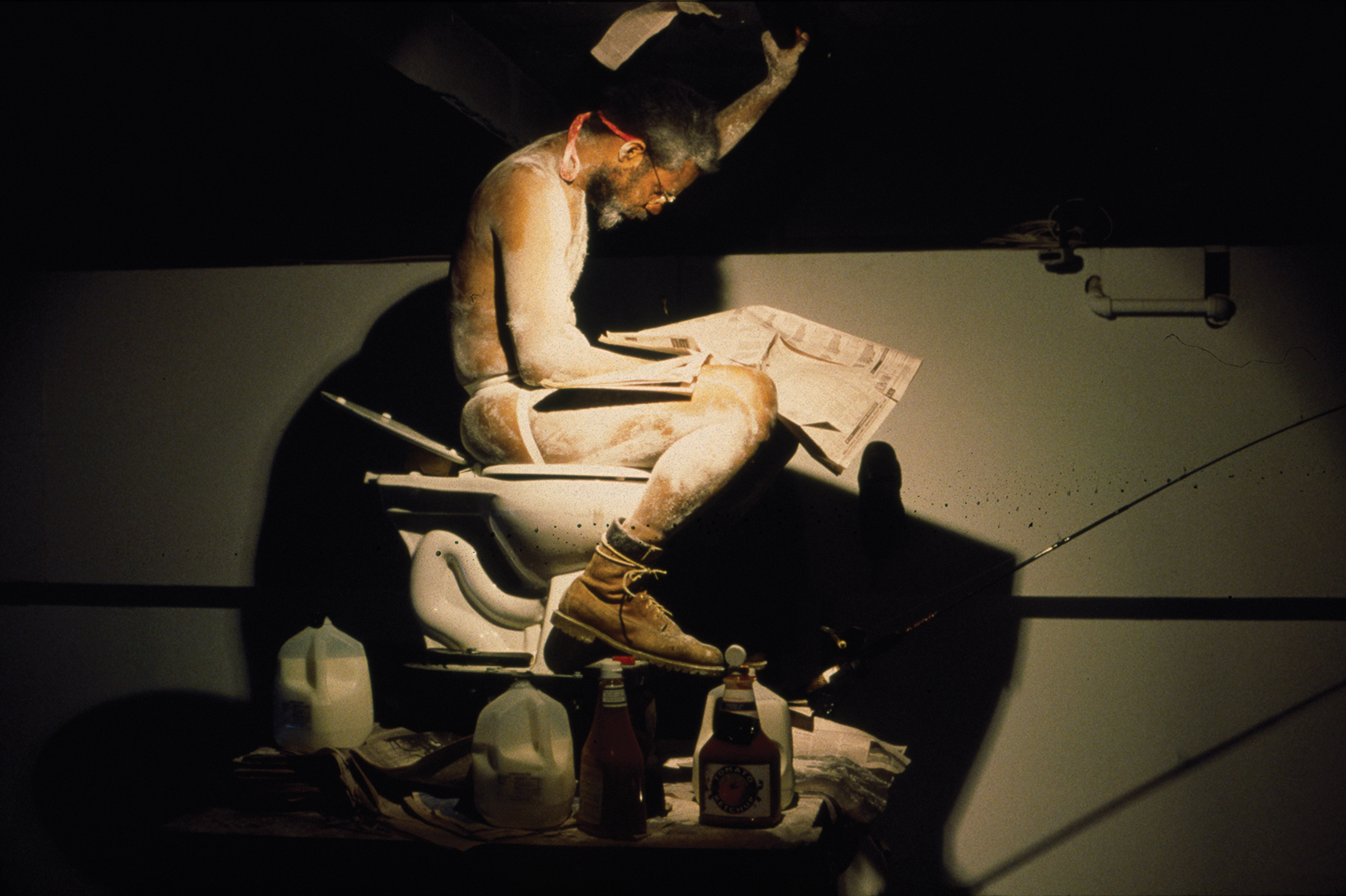

The work of Pope.L, who years ago anointed himself, satirically, “The Friendliest Black Artist in America,” is some of the show’s most disturbingly spectacular, particularly Eating the Wall Street Journal (2000–14), a still from which graces the cover of the exhibition catalog. Placed immediately within one of the Walker’s three exhibition entrances,21 this is a reconstruction of the aftermath of the original performance wherein, for several days, Pope.L sat in a gallery atop a toilet on a 10-foot tower, covered in flour and dressed in a jock strap, silk tie, gold watch and work boots. He continuously read and ate strips of the newspaper with the aid of ketchup and milk, and periodically regurgitated the remnants onto spectators and the floor below. This performance exceeds most others in the show in terms of its primal referentiality and intersectional antagonisms—toward both the worship of capital and the anesthetized aesthetics of the gallery—bringing to bear a host of cross-cultural associations and performative strategies, contemporary and historic. Many writers have called his persona in this piece “shamanic,” and I think the artist’s alchemical procedures—both physical and conceptual—account for this honorific designation.22 The presentation in the Walker is a performance relic—Pope.L no longer activates this work—and the installation tells most of the story with the help of a small video monitor in the corner of the reconstruction showing him in the original work, holding onto a ceiling beam, rocking back and forth, absorbed in his process. Oddly forced is the installation’s addition of copious “mixed media” splatters representing what would have come from Pope.L’s bodily refusal to absorb The Wall Street Journal. As Cassel Oliver writes, “One dare not feign ignorance of what this artist is projecting because as viewer and spectator you are implicated in the work.”23 Pope.L calls us out.

Much of the humor coursing through Radical Presence—and there is a great deal—employs a light touch, at least superficially. Jayson Musson (aka Hennessy Youngman) created a series of short-form YouTube videos, Art Thoughtz (2010–12) in which Youngman, a hip-hop art impresario, improvises learned and hilarious expositions for his audience (whom he addresses as “Internet”) on art-world topics like “How to Be a Successful Black Artist,” “Performance Art,” “Bruce Nauman,” and, most generally, “How to Make An Art.” A brief theme song playing during the credits quickly quips, “White folks like how we know that stuff.” This triangulates and puts a fine point on both Youngman’s appeal and the racism inherent in the supposed unlikelihood of this persona’s subject position.

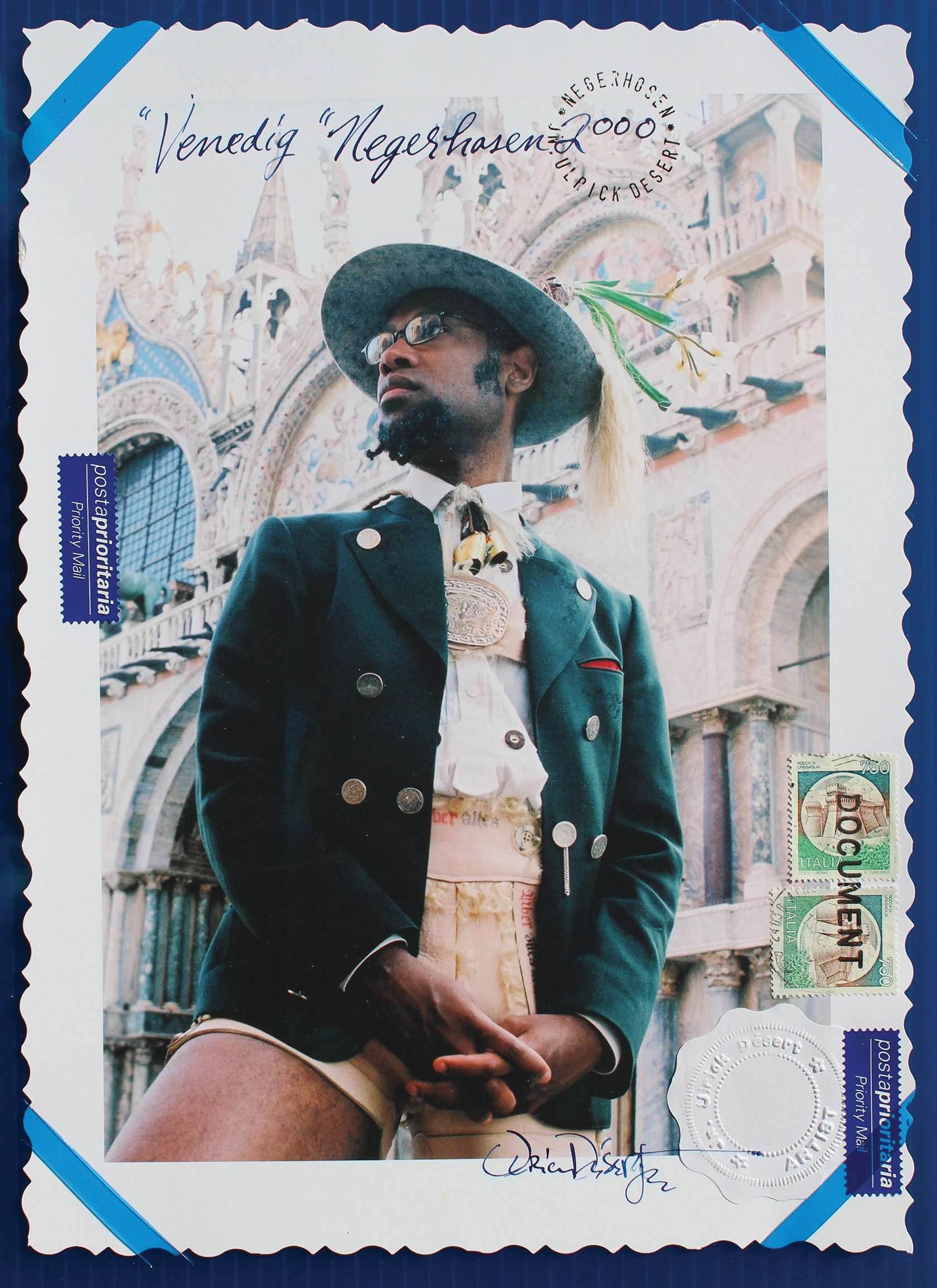

Jean-Ulrick Désert, Negerhosen2000/The Travel Albums (detail), 2003. Forty digitally printed images, pigmented inks, and pencil on archival paper with mixed media collage; 8 1⁄4 × 11 3⁄4 inches each. Courtesy the artist.

Two photographic series in the show document the traveler’s common experience of interacting with others while embodying the consummate “outsider.” In Negerhosen2000/The Travel Albums (2003), Jean-Ulrick Désert wears short, pale pink24 leather lederhosen during a summer tour of Germany, interacting with strangers and documenting their reactions to his sexually and ethnographically suggestive look in his own handwriting over the photos, postcard-style. In Number 14 (When A Group of People Comes Together to Watch Someone Do Something) (2012), photographs document artist Xaviera Simmons on a summer train ride in Sri Lanka, dressed in shorts and a tee shirt. The incongruity of her apparel in the context of Sri Lankan modesty standards leads the artist to gradually layer on all of her traveling clothes, then reverse the sequence, in the middle of the train, fascinating her circumstantial companions, who finally offer their bemused assistance in her costume changes. In the moment of her performance, Simmons was actually engaged in an improvisational response to experiencing risk, having failed to consider another culture’s mores about the concealment of women’s bodies.25 Her routine nevertheless reads like a long-form, deadpan, somewhat inscrutable practical joke, but one both authored by and played on the artist herself.

Dave McKenzie, Edward and Me, 2000. Still from digital video, color, sound; 4:25 minutes. Courtesy the artist, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, and Wien Lukatsch Gallery, Berlin.

Clearly, the work presented in Radical Presence is consequential, but it is never solely polemical. Many artists’ contributions lend themselves to multiple interpretations, enlivening a zone simultaneously political and poetic. I was most compelled by these works, by their indeterminate experimentation, their engagement with the languages of dance, jazz, and other modes that render mutable their medium by continuously shifting, continuously responding. It’s evident that most of these works began with a score, an intention; they’re not purely situational improv (even if, as was the case with Simmons’s work, the performative plan arose in the split-second before she began her sequence). Some of these performances seem superficially uncomplicated, based in quotidian actions: in David Hammons’s video Phat Free (1995–99), he kicks a galvanized metal bucket down city sidewalks at night; in the video Edward and Me (2000), Dave McKenzie dances alone outside a deserted grocery store’s entrance at night. But these repetitive acts are deceptively simple. The intensity of Hammons’s forward progress is evident as the noisy, arrhythmic kicking wears on. He is a racket-raising trickster; the languid confidence of his soccer-practiced movements belies an intent to activate ideas around sonic boundaries, the politics of public space, gentrification, habitation, habituation, willful negligence (“kicking the can down the road”), and even death (“kicking the bucket”). McKenzie’s video references the movie Fight Club, and his movements are intended to approximate and extend those of star Edward Norton’s from a scene of that film.26 The footage of McKenzie’s act is winkingly aspirational, edited with all manner of fades, zooms, reversals, and jump cuts, but the video quality and lighting are reminiscent of surveillance tape. His modern, street, African, and self-determined dance movements clearly surpass the talents of his cinematic twin, but the deeply static, mundane setting indicates the unlikelihood of such talents being recognized. The “training” dance becomes a hectic trance animated by a spirit akin to blues, at times rendering him kicking and gyrating on the ground, performing a dance of frustrated exhaustion. McKenzie’s intervention pivots on complicating and even nullifying the aspirational idol-worship so common in affective relationships to pop-culture, while simultaneously signifying the power of conducting one’s own body thusly in actual public space, deserted or not.

Some of these acts can seem inexplicable, but they are not incomprehensible. To me, the reward of performance work done well is getting to watch that shifting transmutation, that change within constancy. To see artists doing that in a way where the rhythm catches you, even while the work simultaneously points to other specific and particular meanings—that’s what makes performance work uniquely resonant.

In this show, critical and political actions abound. But many artists’ efforts finally bend toward the abstract, the supra-political, the outer limits of what can be thought and named. These artists investigate what Cassel Oliver refers to in the catalog’s preface as “uncharted otherness.”27 These are playful, perpendicular pronouncements; their refusal of all things normative leads to statements of transformation and reinvention. Much of this work is music and dance, from Patterson’s early experiments and Terry Adkins’s 18-foot-long “arkaphones,” played on opening day and hanging from the ceiling at the show’s main entrance thereafter, to the expansive, writhing, indeterminate, emergent bodies produced by Jacolby Satterwhite. In his Reifying Desire series of videos, Satterwhite inhabits the erotic possibilities of imagined or future selves in animations derived from drawings of structures and worlds seen by his mother (who suffers from schizophrenia), as well as live action footage of him dancing in the woods or barebacking gymnastically with a vegan-bakery-owning porn star.28 In the resulting works, which include the costumes he fashions and wears for live, solo dance performances, techno- and bio-mediated bodies generate their own consensual realities of pleasure and being.

Lorraine O’Grady, Art Is…(detail), 1983/2009. Chromogenic print, ed. 5/8 with 1 AP. Courtesy Walker Art Center.

A movement toward audience interaction and collaboration animates much of this work, including Sur Rodney’s Free Advice July 6, 2008 (2008) intervention, in collaboration with Hope Sandrow. In the video documentation, Rodney offers just that to passersby on a country road. A series of color photographs record Lorraine O’Grady’s Art Is…(1983/2009), an interactive performance she conducted from a parade float in Harlem. O’Grady and her assistants, dressed in white and carrying gold-painted picture frames, jumped on and off their parade float, a giant, open, gilded frame itself, to “frame” the audience and take their pictures in a playful effort to collapse the art/audience divide. From the evidence, the public looks gratified to oblige the reversal. Other dance-related works, including those by Senga Nengudi and Maren Hassinger (who for many years have also frequently collaborated), widen the lens of Radical Presence to include performances whose intentions seem more exploratory than critical, intent on finding meaning in the quotidian and within embodied human relationships. Nengudi’s Hands video (2003–12) and Hassinger’s black-and-white photos documenting Diaries (1978), ensemble works she choreographed based on daily activities, counterbalance the artists’ more subtly political output. Nengudi’s RSVP (1975–77), a sculptural work using a variety of “skin-toned” pantyhose tacked to the wall and weighted with sand, is meant to be engaged by dancers (Hassinger herself, on opening weekend) who intertwine their limbs within it, stretching their physical limits against the limitations imposed by the piece and generating meanings inflected by both feminism and racial theory.

Theaster Gates’s work in the show was a piece called See, Sit, Sup, Sing: Holding Court (2012), a welcoming set-up of tables, chairs, and old chalkboards repurposed from a closed public school in Chicago. Installed immediately inside one of the exhibition’s main entrances, special guests and the general public were invited to rest, think, talk, and “hold court” on any subject there throughout the run of the show.29 When he activated the work himself, performing live on an afternoon in mid-November, he began in character, performing the arrogant, successful artist and referring to himself as a “cultured primitive” of whom we could ask questions. Nuanced in its consideration of interpersonal racializing tendencies, this highly affected performativity quickly gave way. Gates spoke transparently and emphatically about the complexities of artists’ needs to understand the functioning of capital and the “infrastructural mechanics of the things we care about” in order to assert power, build platforms, and “innovate forms” in the art world and beyond. He addressed the shrewd realities of maintaining a multi-platform practice like his, diagramming his many roles (“tenured dude, artist, and black radical”) for the audience in detailed, scrawling, nearly-illegible scripts and graphs, and he discussed the importance of maintaining the bedrock of experimentation in an ethically invested art practice. Gates’s talk offered a call to action, learning, and empowerment for artists. As he said, “I want to talk about help as a tool.”30 When the crowd stood up to clear the chairs after his talk, someone I didn’t know turned around and said to me, “That was fantastic.” I left singing, and asking, what if?

——

In writing about this show, I find myself most often recounting what the artists did, what actions they took on the street or in the gallery or in their studios, rather than how those acts came to be represented (i.e., in what medium that action is shown, through what lens, in what colors). In the very first line of the preface to the exhibition, Cassel Oliver writes that Radical Presence is framed around visual arts practices rooted in action.31 Tavia Nyong’o writes in her essay for the exhibition catalog, “Performance is characterized by its radical availability.”32 By “availability,” she is referring to the action’s capacity for being known through all manner of media and techniques. She is not referring to its initial immediacy, in space and time, at the moment of its occurrence, but to its mediacy within many aesthetic formats, including telling the story. Performance’s immediacy—its presence—is actually countered by the mediacy necessary to continue to show it once it has taken place. The nature of this exhibition is that it’s not all there at once, never wholly present or recoverable. It must handle the problems of experiential salvage, documentation, and re-presentation essential to any exhibition devoted to live performance and embodied actions.

Performance is ephemeral by nature. And though this show’s structure incorporates numerous intermittent live performances and activations both within the exhibition space and beyond it, the “live” is, more frequently, absent. To make up for this, we are given a dizzying amalgam of objects (remnants and relics from actions taken, or an action’s primary tools), recorded documentation (videos, photos, slides, and sound), several performative works that exist only as videos, and installations that are meant either to invoke a previous performance or to structure space for planned or potential future acts, waiting to be activated by artists and/or the public. The objects here are precursors, outcomes, or remainders, whereas during the act itself, we watch the story being told. When the narrative plays out in front of us, it’s got all the excitement of an athletic event.

Pope.L, performing Eating the Wall Street Journal (2000), at The Sculpture Center, Long Island City, New York, 2000. Courtesy the artist.

Perhaps nothing indicates the distance between the memorializing object and the act itself better than the copious spatter around Pope.L’s Eating the Wall Street Journal (Walker version). Its application surrounding the installation indicates a ferocity of ingestion, expectoration, and repulsion from a human body. But the materials list for the installation— “plywood, newspaper, toilet, mixed media” —fails to include any mention of the artist’s bodily fluids, suggesting that this big, bold entrance piece is an aestheticized and cauterized representation of an originating transaction within a contemporary art space that transcended most enculturated behavioral protocols. We have, here, a 3-dimensional picture, a stage set mimicking a transcendent experience.

My main complaint about the Walker’s version of Radical Presence is that they buried the lede. The exhibition space had three entrances. Depending on which one you entered, it might have been quite a while before you encountered substantial footage of someone engaged in a risky, symbolic act (let alone a live body, performing), even though that’s what this show was built on. The Studio Museum accomplished this in its necessarily more compact installation: as soon as you entered the main space of the show, you found yourself amongst multiple videos and projections of performances, all caught up between bodies engaged in all variety of risky business.33 The trick of recorded performance is that, even though your brain knows it happened before, your body believes it’s happening right now. At the Walker, these visceral works were mostly nestled in a cave at the center of the show, invisible from every entrance. The spatial organization missed the chance to activate this body-to-body responsiveness, the innate excitement of witnessing a narrative transpire. The Walker cocooned many artists’ original risks within a more conservative art-historical strategy, foregrounding an object-based program rather than one based in time, risk, and uncertainty, the very program embraced by many of the artists in the show. The tension between the art market and unmarketable acts manifest in this exhibition as it was mounted at the Walker amounted to an exhibitionary disavowal of what makes performance so enlivening—witnessing the body in the midst of a task that challenges what we consider normative, to open us up.

As the audience of an artwork, we are always complicit in its meaning. This, I believe, is especially true with live performance. Risk taking is not just for the artist: it’s in letting yourself be changed in response to the work. Performance art pushes us toward certain kinds of literacy, as well as an acknowledgement of our own illiteracy and ignorance. Performance art can also be an equal-opportunity alienator. Identification has its limits, and these artists push those limits. These artists break rules that others abide by—black people, white people, all sorts of people.

Curator Cassel Oliver remarked during the opening weekend panel discussion: “I wanted it [Radical Presence] to be an exhibition that was alive, that was animated . . . because it is a living history, something that continues to unfold, to yield . . . ” This show is unusually alive, in ways both foreseen by the curator and entirely unforeseeable. In addition to the live performance program, the show incorporates both additive and iterative processes. In accumulating new works as the artists complete them, its curatorial modus operandi is unusually open, producing a show that changes over time and allows insight into the development of an artist’s practice.34 The exhibition seems to live differently in each host city and institution, incorporating works held by host institutions,35 supporting new live performances, and spilling out beyond the usual borders of museum programming, all of which complicate the catalog’s function as historical record. The thoughts and lives of the artists change as this show moves through time, as well; Adrian Piper’s decision to drop out of the show during its run in New York and Terry Adkins’s untimely death have both altered its initial balance immeasurably.36 And this show is alive in time in the largest political sense, as well, evidenced by how much has happened nationally since work on this show began: the Supreme Court’s gutting of section 4 of the Voting Rights Act; the tragic, enraging losses of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, and numerous others; the repurposed echoes of Garner’s last words—“I Can’t Breathe”—in the actions of millions of protesters, famous and otherwise; and an ever-expanding series of occurrences galvanizing a renewed racial justice movement in the United States. Through the operation of forces both inherent and external to it, this show’s impact increases over time.

Radical Presence is continuously in development, and that is a good thing. The show’s hosts in New York City did a magnificent job collecting resources on every artist’s practice, creating an immense archival website, radicalpresenceny.org, that includes expanded introductions, interviews, additional performance videos, and other documentation.37 It can’t compare to the experience of walking through and having the work jiggle and upend you, of knowing yourself newly in relation to it, but long after the elements of this show have disbanded, the exhibition has nevertheless resulted in this wholeness. What’s been there all along—the history and practice of black visual artists engaging in performative strategies—is no longer absent or partially buried in obscurity. We never have to not know these things again.

Sarah Petersen is a multidisciplinary artist currently teaching at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.