Prologue

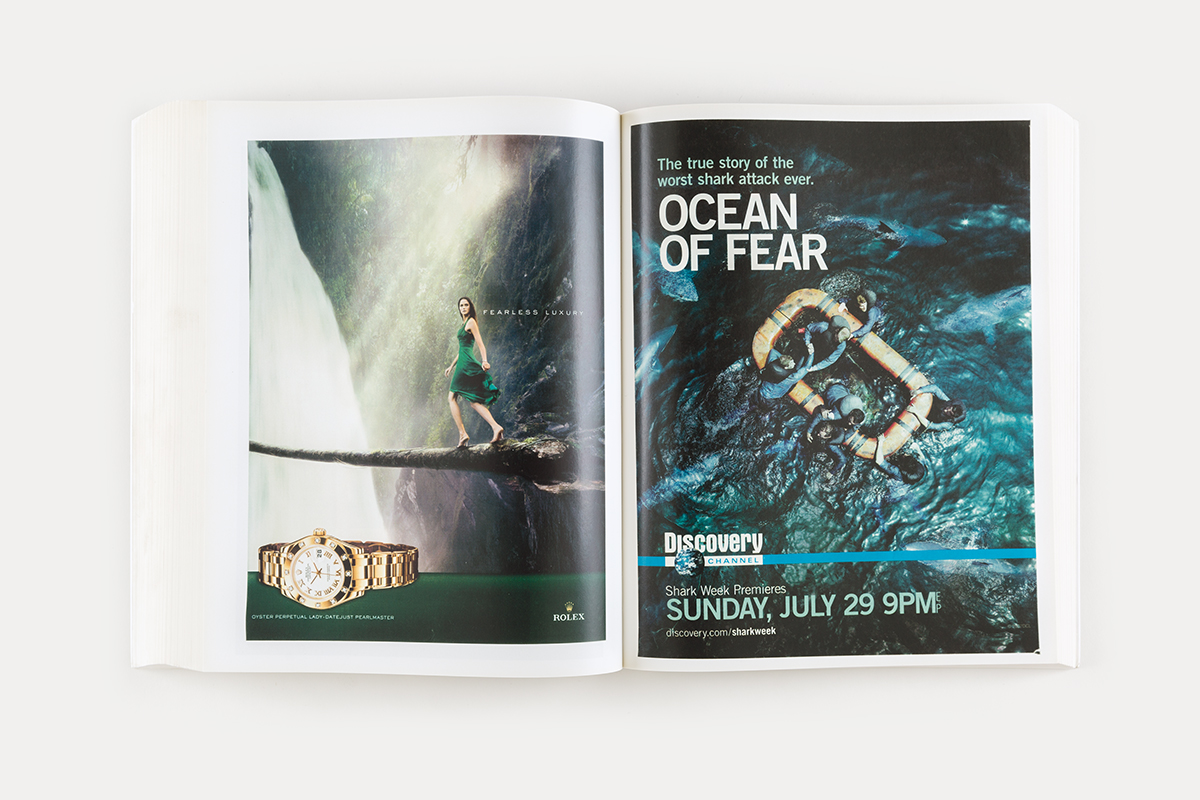

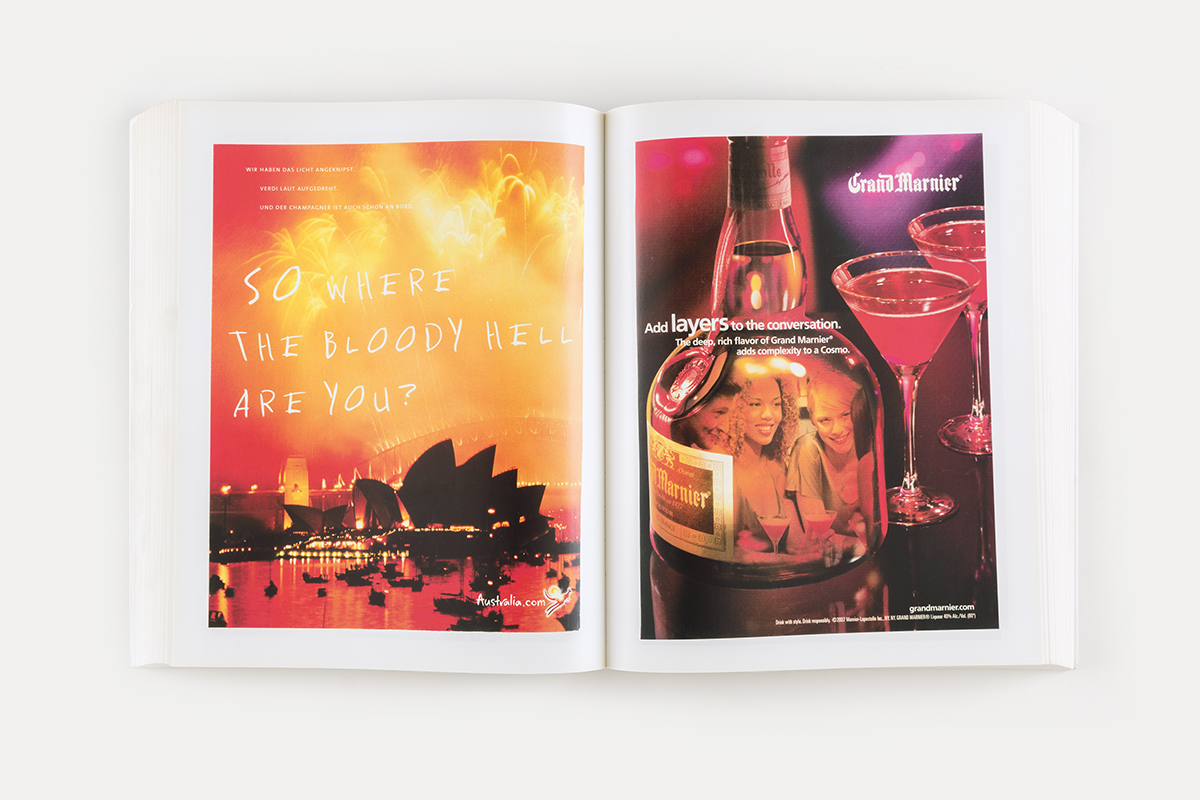

It’s good bathroom reading because it’s barely reading at all. The Ringier Annual Report 2007, a weighty 840-page volume designed by the Swiss artist duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss, consists almost completely of magazine ads. The collection has been pulled from recent mass-market print magazines with a global range of target audiences, indexed by color, by product, or by feel—cool green ads for razor blades, a hot orange ad for Australia. Each is reprinted at a slightly degraded quality, with a white border instead of the magazine’s full bleed, like scans of tear-sheets from what we imagine is a bulging archive. The project takes the advertising that underwrites publishing in the old model, disassociates it from its purpose, and represents it as visual filler. Scan the text, appreciate the glossy composition of a pair of spearfishing guns or a motion-blurred Bentley, and turn the page.

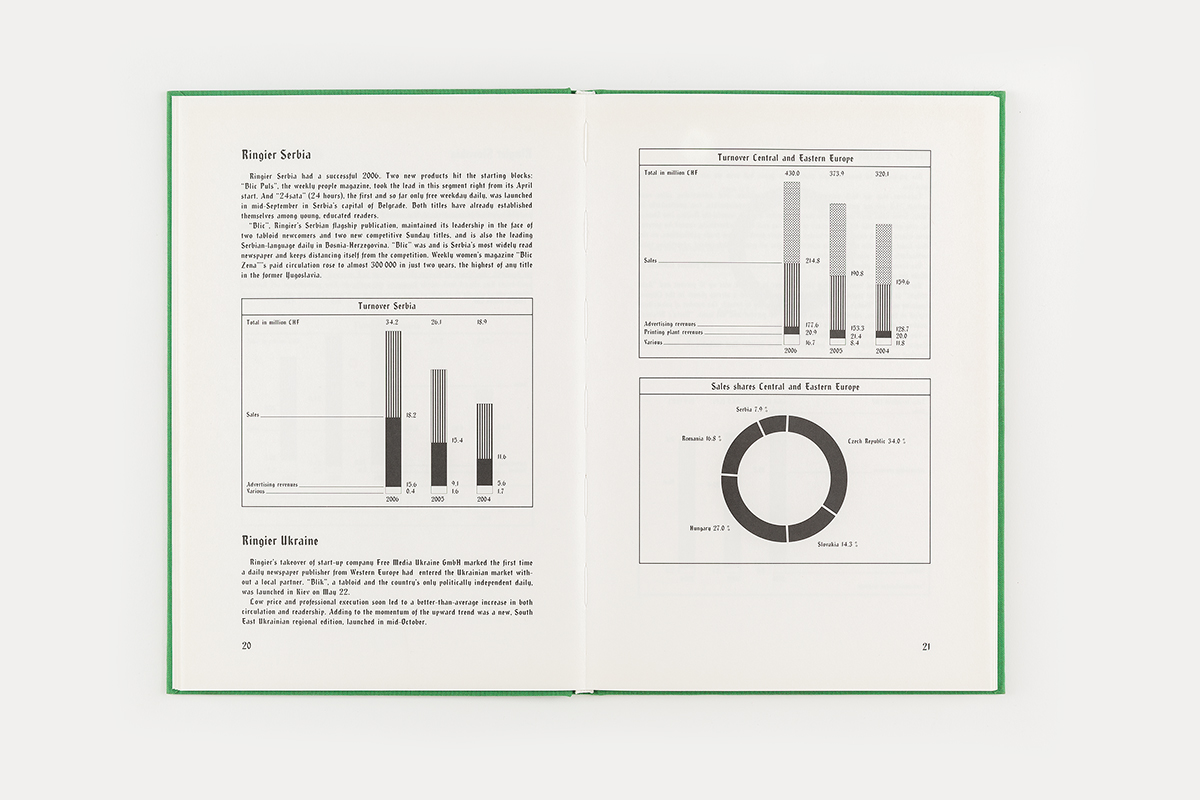

Beginning with the 1997 fiscal year and continuing to this day, Swiss publishing group Ringier AG has invited artists to design or otherwise intervene in their annual financial disclosures. The results illustrate a friendly repartee between patron and provider. “Our company,” writes publisher Michael Ringier in the prologue to the 2007 report, “measures itself with the same yardstick [Fischli and Weiss] apply to their work: If you’re not ambitious enough to be the best, you’re not good enough for second best.”1 If these are great artists, their participation is a testament to Ringier’s taste. Even so, there’s a little cheekiness to the way Fischli and Weiss’s layout emphasizes the essential commercialism of the publishing enterprise. And theirs is not the only edition to threaten to exceed their host’s largesse. Wade Guyton took a resource-intensive approach to the 2014 report, prefacing it with a life-scale photograph of one of his paintings reproduced across hundreds of pages. The latest report, for 2017, is by Katja Novitskova and contains lowres images printed triumphantly in high quality full color and bound in a transparent plastic cover with French flaps and a pocket in the back for a booklet of tables and graphs.

Fischli and Weiss, Ringier Annual Report 2007 (Zurich: Ringier AG, 2008). Courtesy of the artist and Ringier AG. Photos: Ian Byers-Gamber.

Fischli and Weiss, Ringier Annual Report 2007 (Zurich: Ringier AG, 2008). Courtesy of the artist and Ringier AG. Photos: Ian Byers-Gamber.

These artists exploit the fact that Ringier agrees to the expense not only of printing but of shipping each year’s report, no matter how large. Copies of the report are mailed free of charge to their stockholders, as well as (while supplies last) to anyone who asks.2 As corporations go, Ringier AG isn’t particularly amoral. The company’s annual reports, therefore, showcase not only artists and their art but also how artists approach what could be complicity, or subversion, or a stable mix of both. The 2007 report is an exquisite corpse of print magazines. All this abstract “flow of capital” lands with a thud on your doorstep. This much Ringier can endure. The rest, after all, is art.

Just Print More

In 1883, Johan Ringier opened a modest print shop in the town of Zofingon, Switzerland. It is now the country’s largest publisher. The 2017 report puts the Ringier AG group’s annual revenue at just over 1 billion Swiss Francs ($1 billion USD). Ringier’s portfolio includes Blick, a German-language Swiss tabloid with three hundred thousand readers; Schweizer LandLiebe, a country-living magazine; a magazine-printing business that runs over thirty titles; and a sprinkling of TV, web, and radio brands. They have properties in Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe. In 2004, Ringier joined with JRP Editions to form JRP|Ringier, which has become a major publisher of artists’ books and monographs. (At present, their catalog includes over 700 titles, some 500 of which are currently in print.3 )Ringier also has an art collection of its own, and each artist who has designed a report is also represented there.4

Ringier AG began the tradition of avant-garde stockholder reports at a moment when print media had started to seem inadequate. From the beginning, artists have stressed the company’s growing pains. Sylvie Fleury, in the 1998 report (the second), interpolates the usual graphs and summaries with lush photos of bound stacks of fashion magazines after a series of her own sculptures, intimating that print media is ready for the recycler. Like Fischli and Weiss, painter Laura Owens’s 2013 report connotes the glory days of print by incorporating layouts and advertisements in the style of the 1940s (most of them with German copy) and including a portfolio of new silkscreen prints that riff on mid-century modernism. Yet the publication was accomplished using contemporary printing methods and through pastiche made possible by contemporary digital indexes. Beatrix Ruf, director of the Ringier Collection since 1995, writes that Owens “emphasizes the continuity linking today’s media techniques to those of the past.”5 There is more at stake here than an empty formal resonance. Print publishing is where “Art meets commerce, intellect meets money,” writes Bernhard Weissberg, project coordinator of the 2013 edition. “Ringier’s annual reports have always been a clash of cultures. This year’s artist [Owens] is taking us back in time, while Ringier is rapidly heading towards the future.”6

Laura Owens, Ringier Annual Report 2013 (Zurich: Ringier AG, 2014). Courtesy of the artist and Ringier AG. Photos: Ian Byers-Gamber.

Laura Owens, Ringier Annual Report 2013 (Zurich: Ringier AG, 2014). Courtesy of the artist and Ringier AG. Photos: Ian Byers-Gamber.

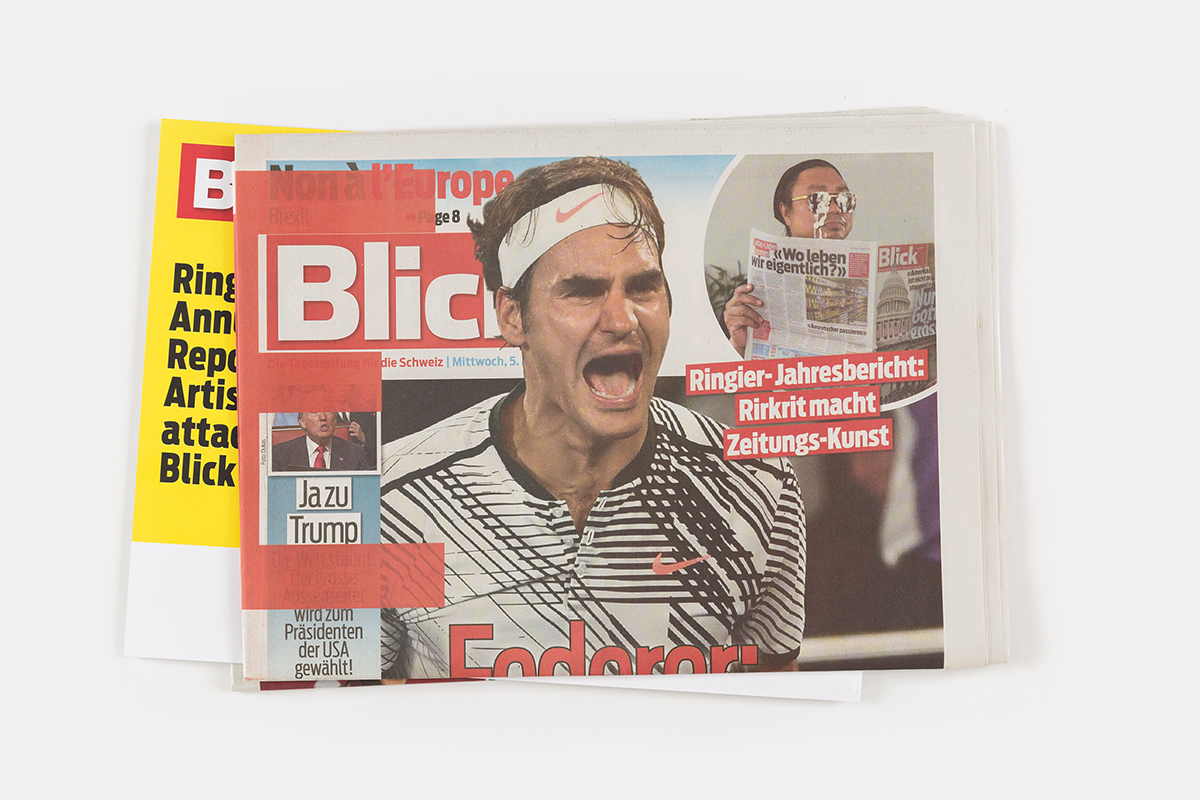

Media are under siege, and media push back. For the 2010 edition, German duo Das Institut produced an altered version of Thời Trang Trẻ, a Vietnamese lifestyle and fashion magazine that Ringier publishes; like a bonus artists’ multiple, the package comes with a set of press-on nails. For 2016, Rirkrit Tiravanija mocked up a double issue of Blick. An insert introducing Tiravanija’s faux daily reads: “Ringier Annual Report: Artist attacks Blick”—in the German and French, as well as English. Tiravanija is pictured reading an issue of Blick with Donald Trump on the cover, an oblique acknowledgement of the latter’s bigoted and vitriolic attacks on the free press. As if seeing no evil, the artist’s aviators are smeared with white foam. Where another’s art would turn media into propaganda, Tiravanija opts for parody instead.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Ringier Annual Report 2016 (Ringier AG: Zurich, 2017). Courtesy of the artist and Ringier AG. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

Inside the Gatefold

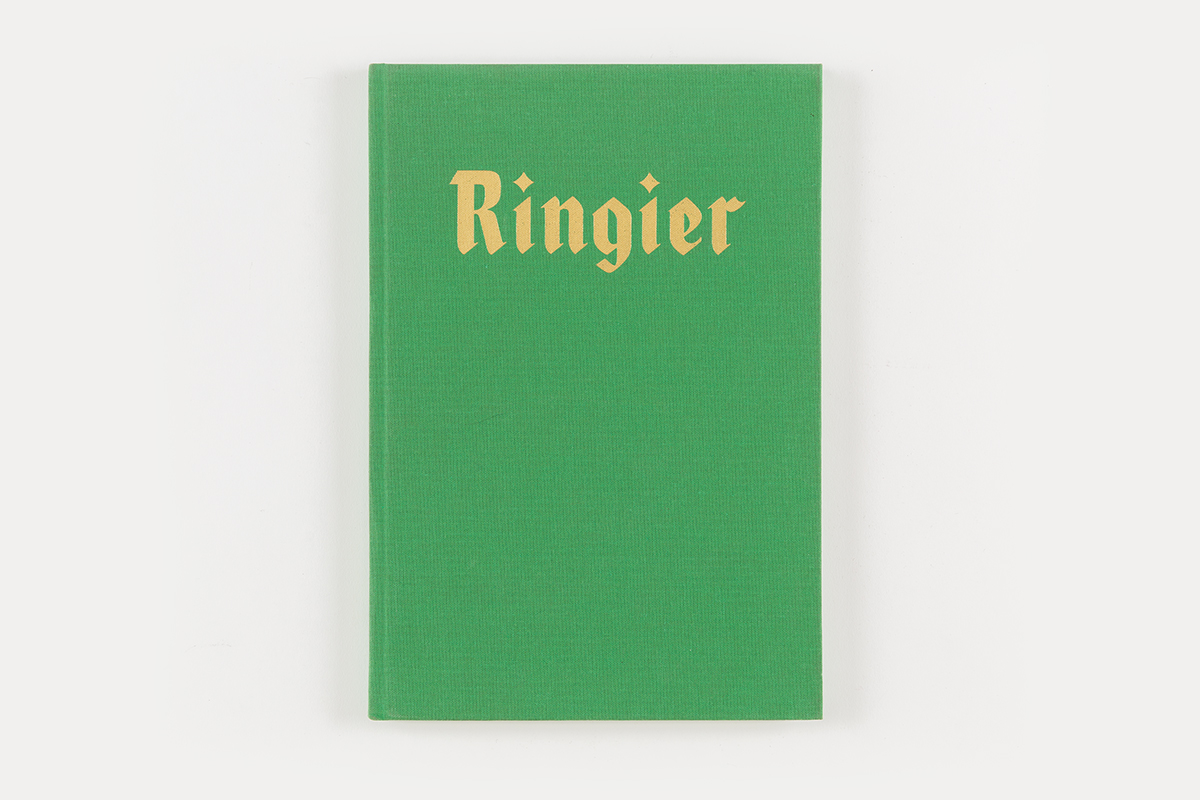

Ringier likely found it easy to laugh along with Fischli and Weiss. Non sequiturs and salacious layouts are meant to round out the abstract financial language of the report itself. “The annual report is impressive proof of art as an integral part of Ringier corporate culture,” reads the company’s website. “The successful feat of balance between sober figures and modern art impresses the financial world while exacting excitement from the cultural elite.”7 Other interventions hit harder. The 2006 report is a slim volume bound with green cloth; no text appears on the cover save the word Ringier, which is stamped in gold foil and set in what Michael Ringier admits is “[a] typeface that evokes Nazi Germany and the horror it has come to symbolize for an entire generation.”8 The font is Fraktura; the entirety of the report appears in its chilling, spiked strokes. This is the provocation of artist Richard Phillips, who—with a design intervention more pointed than Owens’s nod to the Nazi era—seems to implicate the failure of the public, and of the culturati in particular, to see the Nazism latent in Germany’s national typeface.

Richard Phillips, Ringier Annual Report 2006 (Zurich: Ringier AG, 2007). Courtesy of the artist and Ringier AG. Photos: Ian Byers-Gamber.

Richard Phillips, Ringier Annual Report 2006 (Zurich: Ringier AG, 2007). Courtesy of the artist and Ringier AG. Photos: Ian Byers-Gamber.

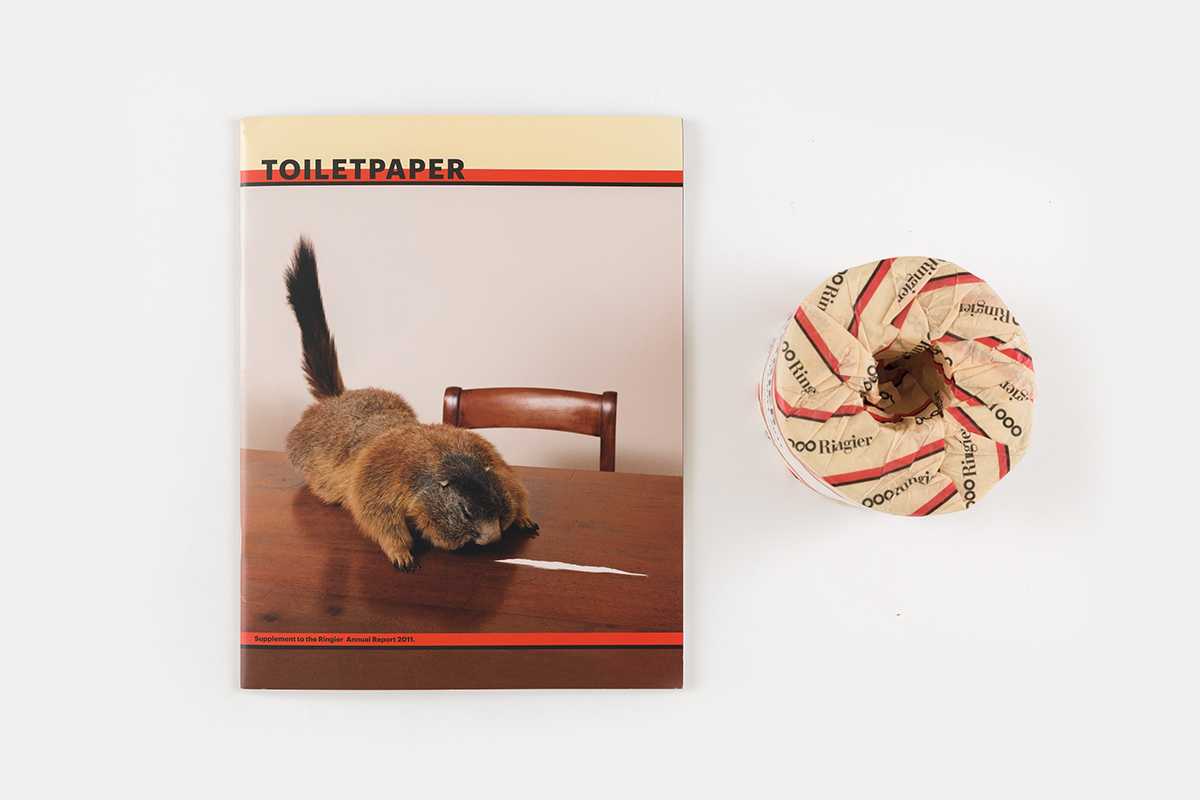

Phillips, though, is simply doing what artists are supposed to do: afflict the comfortable. In the back of the book is a suite of sketches based on photographs taken from both vintage and digital media. “The ‘Fuck you’ in one of the pictures and depictions of naked women—none of these,” speculates Mr. Ringier, “are likely to have been part of any other annual report.”9 It is a proud moment when your company has achieved a status, reach, and power that an artist finds worth challenging. Perhaps predictably, Maurizio Cattelan also provided a bitter satire. His 2011 report arrives in two parts loosely packed in a cardboard box: on the bottom is his artist project, a new issue of his magazine Toiletpaper, with a cover photo of a squirrel contemplating a line of cocaine; on top is the report itself, wrapped around an actual roll of toilet paper. To Cattelan’s package, the publisher has added a preface on a slip of paper: “I am pleased to present you with your copy of the 2011 Ringier Annual Report,” it reads, “which takes the form of an all-encompassing work by the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan. This publication once again demonstrates how Ringier always accords carte blanche to the artists it commissions to design its annual reports. It is testimony to the open-mindedness with which Ringier, as a forward-looking media company, also grants free expression to less conventional viewpoints.” “Cattelan,” they write, “has put us to the test.”10 If artists challenge authority, conventions, and received wisdom, so, asserts Ringier, does our company.

Maurizio Cattelan, Ringier Annual Report 2011 (Zurich: Ringier AG, 2012). Courtesy of the artist and Ringier AG. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

You Hold in Your Hands…

The publishers anticipated that their 2012 report, designed by Philippe Parreno, might baffle some of their constituents. As with other artists’ riffs on Blick and Thời Trang Trẻ, the report is formatted like DOMO, Ringier AG’s in-house journal. The document comes packaged in a colorful, geometric design printed on a poster that is wrapped around it like a present and taped shut. (There is a card, too: “Can I just tear this open?”) The short introduction from the publisher and chief executive officer then makes a version of the statement found in nearly every edition. “You are now holding the Ringier 2012 Annual Report in your hands,” it begins. “It is wrapped in a work by Franco-Algerian artist Philippe Parreno.” It is wrapped decoratively, sure, but what you hold in your hands is more than a cleverly designed informational booklet; it is also an original work of art. “This is a present that requires you to make a choice,” they write. Whatever you choose, it will still be art: carefully undo the package and preserve the poster in a frame, or better yet, leave it sealed and admit that the design is art enough; rip it open and discard the poster, and you will have otherwise performed the artist’s work for him.

These encounters with difficult art—art that you can nonetheless handle—demonstrates the reciprocal blurring between art as mass media and mass media as art. The fungibility of the artists, their reach, and their adaptability to less rarified conditions reflects, to Ringier, the values of their company. And, like magazines on a rack, perhaps it’s better if people take art for granted, rather than sacralize it or avoid it altogether. Michael Ringier makes this plain: “I go into a gallery with the intention of looking at art, so I prepare myself quite consciously for a particular situation. In a company, it’s different. [I]t’s just there. It stands there—it just hangs on the wall and affects people’s perception very discreetly. I can imagine that the effect of the art—in the way that we show it—is even more profound than when you go into a gallery.”11

Ringier’s running theme is that the qualities that make successful businesspeople are the same that make successful artists. An artist’s fearlessness, decisiveness, sensitivity, intelligence, subtlety, resilience, et cetera lend themselves to the entrepreneurship of the business class. As Ben Davis observes, although we associate artists (and the historical avant-garde in particular) with working-class sensibilities, it’s more accurate and more useful to think of artists as middle-class entrepreneurs: small business people working for their own brands.12 Ringier continues: “Journalism and art both pose questions, both awaken emotions. They polemicise, they polarise, and perhaps their most significant common factor is that both have to be highly intelligent. . . . Art deals in emotions; art deals in uncertainty. Actually, when we make decisions about art, we act exactly the same as for business decisions. Getting involved with art is a kind of training for making decisions in business.”13 Intuition can be learned, and art can help. In this formulation, artist and entrepreneur alike benefit from having wide-ranging tastes, wherein financiers can enjoy contemporary art and artists are accustomed to large sums. When the two meet, neither will be stunned by the encounter.

Each report is a work of art that also advertises the artist. The report design introduces each artist and his or her work to an audience of investors who may want to invest in art. “[I]n our highly competitive media market,” writes Michael Ringier, “there is no room for art for art’s sake,” insisting that even l’art pour l’art can, and should, be instrumentalized for investment’s sake.14 When Beatrix Ruf calls Laura Owens’s suite of silkscreen prints “special and rare,”15 she upholds a wider cooperation between the artist and the corporation (which includes, for example, another Owens monograph and the Owens works in the Ringier Collection), and a synergy between complicity and subversion. Projects that begin as interventions in a corporate routine become subroutines, and the artists’ own sales numbers, in whatever small way, are calculated in next year’s returns.16 Such art must be as expedient as the companies that commission it. The romantic disavowals of Modernism, from Futurists dying in the trenches of the First World War to Jackson Pollock urinating in Peggy Guggenheim’s fireplace, reflect the rough purity of twentieth-century ideologues. These will not see the future; some new hybrid will.

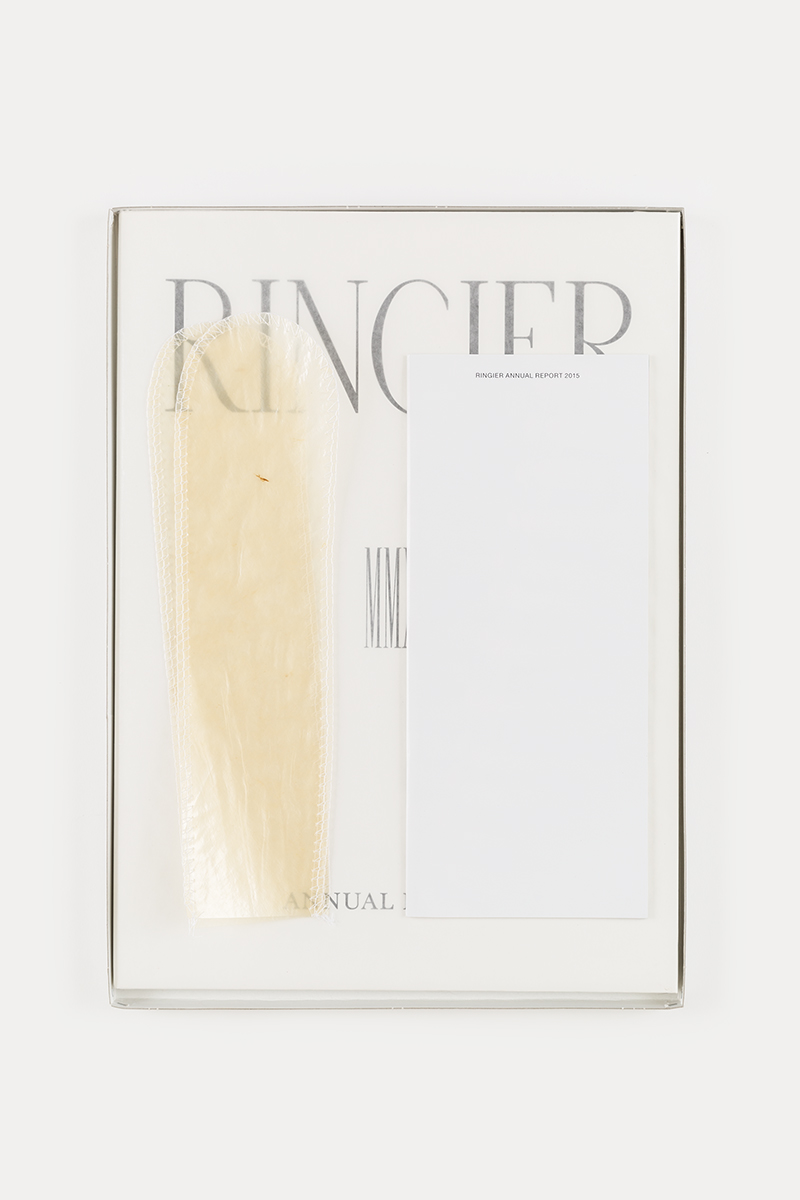

Helen Marten, Ringier Annual Report 2015 (Zurich: Ringier AG, 2016). Courtesy of the artist and Ringier AG. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

Helen Marten, “IX. ALONGSIDE—hamburger mince production,” Ringier Annual Report 2015 (Zurich: Ringier AG, 2016). Courtesy of the artist and Ringier AG. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

Epilogue

“Helen Marten,” writes Ruf in the 2015 report, “has chosen the sausage” for her theme. It is a metaphor, she acknowledges, for the publishing process. “However uniform sausages may appear, they encompass a wide range of different materials, as indeed does the output of an international media enterprise.”17The report arrives in a shallow cardboard box. Open it and two sausage socks lie there like a pair of cotton gloves, on top of a portfolio wrapped in wax paper. Inside is a series of 16 photographs taken at two Swiss sausage making factories that illustrate the procedure from start to finish. Most of the photos are bloody and raw, like VIII. ARTERIAL FLOW—making Blutwurst, which shows a pail of animal blood being added to the mix. A couple make dry jokes, such as XVI. CONNECTIVE TERMS—office particulars, which depicts a plastic piggybank among the three-ring binders in a factory’s office. But the first plate nearly says it all: I. INSIDE/OUTSIDE—soaking pig intestines. They are soaking alright—dozens of ghostly white tubules hang on the water’s surface from pockets of air. Marten’s inside/outside take on the commission makes explicit what the commission is—a willingness to work within the system, not without it—and to perhaps recognize the importance of Ringier AG’s cultural triad: mass market newspapers, high-end art books, and a respectably risky collection of contemporary art. The casings in the photo will eventually serve as the outside of the sausages. But for now, it’s the artist who’s inside.

Travis Diehl has lived in Los Angeles since 2009. He is a recipient of the Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant (2013) and a Rabkin Prize in Visual Arts Journalism (2018). He is an editor at X-TRA.