I sought a theme and sought for it in vain, I sought it daily for six weeks or so. Maybe at last, being but a broken man, I must be satisfied with my heart, although Winter and summer till old age began My circus animals were all on show, Those stilted boys, that burnished chariot, Lion and woman and the Lord knows what.

-William Butler Yeats, The Circus Animals’ Desertion, 1939.

The entrance to Third Mind sets the stage for Richard Hawkins’s characteristically varied forms and subjects.1 In this introductory space, the exhibition’s only two paintings hang in juxtaposition with two cut-rubber masks and a stacked table sculpture. Despite its presentation of a multiplicity of works, the entrance gallery is languid; the gross volume of unattended space renders these works negligible instead of exceptional. It is an installation conceit antithetical to Hawkins’s celebrated potency as an artist. The parsimonious installation trivially articulates the pristine proportions of the galleries instead of charging the exhibition spaces with the intensity of his collage process.

The organization of the other five rooms is an a-chronological meandering of works looping fantasy into daydream into obsession, evoking a mood managed more by antidepressants than by Ecstasy. Modeled on the labyrinth and not the laboratory (Hawkins pulled off both installation strategies in his 2008 survey exhibition, Of Two Minds, Simultaneously, at the De Appel in Amsterdam), the entire corpus of the show eases into a wistfully arranged systematization of infatuations. Disembodies zombies, textbook illustrations of Hellenistic sculpture, “cute” heavy metal guys, mystifying dollhouses, the vivid dragonfly collages, all evidence a private craving. And although the works often fall short of producing a voyeuristic thrill for viewers, it is never in doubt that Hawkins is pleasured by his own act of collecting, cutting, and collaging.

The exhibition takes its titled from a William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin book entitled The Third Mind, published in 1978. This book’s objective was to employ the straightforward exercise of “cut-ups,” the combining of dissimilar texts cut from various sources into new narratives and anti-narratives, a literary technique made popular by Burroughs in the 1960s. With some exceptions, Hawkins’s Third Mind flaunts an abbreviated compendium of his own countless versions of the notion of “cut-ups.” In addition, two reinforcing displays of his output are shown in other parts of the Art Institute. Vitrines in the Ryerson Library feature a selection of Hawkins’s ephemera and altered books. A collection of five paintings occupying a small gallery in the new Modern Wing of the museum smartly underscores Hawkins’s lecherous subject matter wrought in tightly cropped, figurative compositions made decorative with his deft use of color and line. Options, not solutions (2004) best illustrates his painting proficiency with its many patterned surfaces and sexually charged tableau featuring three male characters in stages of undress.

In an essay on Hawkins for Afterall, Dominic Eichler observes that “tradition has it that one reason for valuing artists is that they are the people who are meant, unlike us, to do exactly what they damn well want to.”2 Hawkins has been enthusiastically embraced for making work that “resists classification” and is “emphatically diverse.” But these characterizations could apply to any number of mainstream self-fashioners in the culture industry. Laissez-faire capitalism, comingled with a canonical-free, theory-free cultural landscape, has produced artists, from Ryan Trecartin to Richard Aldrich, who embrace the freedoms of instinctual production. Hawkins is considered the patriarch of this tradition, and the autonomy that he has brandished within his practice for the past twenty years gives him near celebrity status among droves of young artists.

“From scholarly artist’s statements to perverse fictional stories and experimental fragments,”3 the Hawkins model–aloof, selfdelighting, and confident in piecing together images, words, and found objects–has become daily practice in a culture contoured by social media’s nodes, ties, links, and connections. Effortless communication has made self-mythologizing de rigueur, and Hawkins’s seductive and wistfully addictive collaging is now commonplace for the rest of us with photo programs on our computers. Compulsive appetites and creative impulses draw on the immediate and wide-reaching venues of Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, re-contouring the landscape of public fantasy and further expanding the notion of heterogeneous production. Within this landscape, much of Hawkins’s collage work manifests as strikingly quaint.

Take, for example, the suite of eighteen collages on small, spiral-bound sketchbook paper, which combine paint, ink, and cutout media images depicting indigenous people. The Greasers vs. the Socs (some of us didn’t even know we were indians) (2004) examines the cultural notions of assimilation, difference, and supremacy while shoring up Hawkins’s own autobiographical record. In 2003, he learned that his family bloodline includes Native American ancestry. With sweeps of paint, crude line drawing, cutout National Geographiclike reproductions of chiefs in westernized garb and abutting notations such as “choosing the cutest Indian,” he builds a handmade scrapbook that is entirely conventional from the standpoint of identity oriented work. Less predictable are the two mixed media paintings hanging in the entrance gallery–Bad Medicine (2009) and Little Pinkfeather (2008). Bad Medicine is assembled from an old terrycloth paint rag that is hastily stretched on a small support. A feather is attached to the bottom edge of the painting while the surface features a circular build-up of colorful impasto paint. Like Greasers vs. the Socs, the paintings employ tropes of talismanic practices, but here Hawkins successfully implicates the ritual of the painter and the accoutrements of the painter’s studio with the kitschified Indian tropes of a dyed turkey feather.

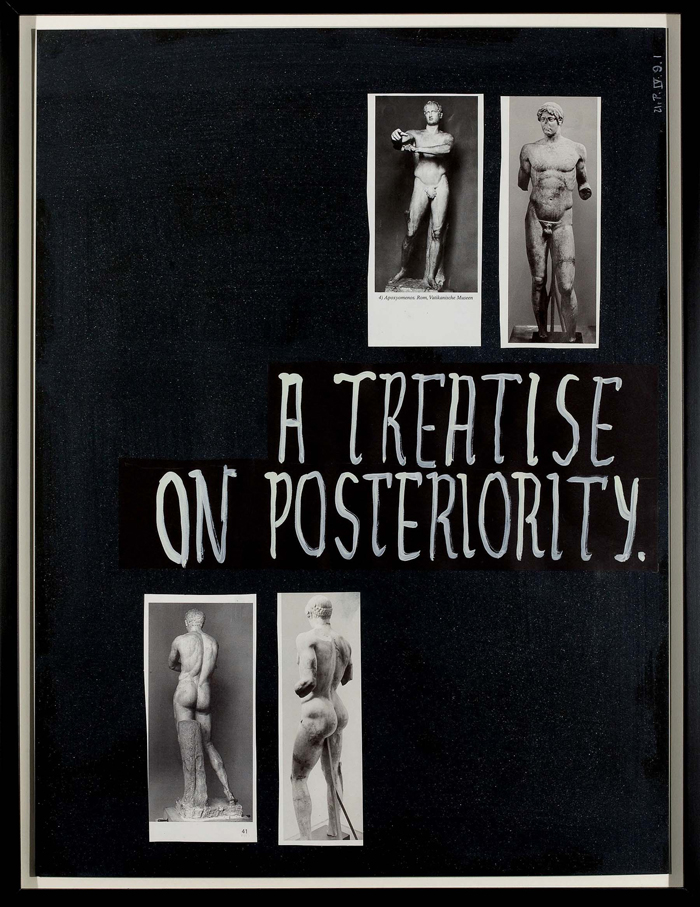

Richard Hawkins, Urbis Paganus IV.9.I. (Posterity title), 2009. Mixed media on mat board, 20 x 15 inches (21 1/2 x 16 1/2 inches framed). Courtesy of Greene Naftali Gallery, New York.

Of course, Hawkins is more notorious for devoting himself to his libido than to his ancestral pedigree. The remarkably funny and sybaritic series Urbis Pananus is an example of a collection or repository as desire. Blackand- white illustrations cut from a German textbook document the fronts and backs of Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic sculptures. The figures are arranged on a black matt board with columns of white, hand-lettered, pseudohistorical, and faux-academic narratives that hold place alongside the mythological personas. Unlike his Dragonfly series (2009), which salaciously adheres a magazine cutout of a young male fashion model to a quickly drawn radiant motif that can only be read as a stylized anus, the ongoing Urbis Pananus collages are worked into a field of negotiated paradox: front to back, fact to fiction, hard to soft, mimesis to abstraction. Perhaps the most important of these oppositions is the blurred line Hawkins evokes between literature and visual art.

The Urbis Pananus series is akin to William Butler Yeats’s Circus Animals’ Desertion (1938). As Yeats surfaced from his soap-bubble colored verse and the influence of Mallarmeinspired poesie pure, his obsession with the true and beautiful gave way to a motley collage of dream states, fantasy, realism, and vain repose that he paraded around center stage in the late poem. From The Lake Isle of Innisfree (1890), with its “bee-loud glade,” to “Lord knows what” in The Circus Animals’ Desertion, Yeats’s poetry grew conciliatory, fragmented, and syntactical over the course of his life, as he was no longer able to reconcile the oppositions of prose and poetry, eminence and transcendence, and symbolism and realism that had shaped his mythopoeic Celtic Twilight years. Similarly, Hawkins’s dreamy, disembodied zombie and “cute” boy collages shape his gay twilight genre, indulging in cliched gestures of romantic desire. Yet the page-like constructions of Urbis Paganus suggest a powerful new form of visual literature. They are compositionally more sophisticated and conceptually profound than most of his lusty mash-ups.

Richard Hawkins, disembodied zombie ben green, 1997. Inkjet print, 47 x 36 inches (54 1/2 x 43 inches framed). Courtesy of Richard Telles Fine Art, Los Angeles; collection of the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

Collage dynamics and the embrace of disparity marked Yeats’s move from a seductive and additive romantic to a dislocated Modernist. Collage and collage aesthetics were the solution to the irreconcilable binaries that foreground the Twentieth-century avant-garde. Whether in the hands of Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Tristan Tzara, or Pablo Picasso, collage “was the language of depletion and deletion, more destructive than constructive in its essence.”4 And as the endorsed language of the “new,” it was as potent in literature as in image making. George Baker’s essay “Viva Hate,” which anchors the Richard Hawkins: Third Mind exhibition catalog, examines theories of collage ranging from its Modernist “stillborn” birth to Postmodernism’s “productivist idiom of the collage artist as engineer.”5 Placing Hawkins in opposition to the Postmodern model, Baker suggests that the “provisional and handmade aspect” of Hawkins’s collages locates him in the unique tradition of the amateur collagist.6 Driven by compulsive urges and pathological yearnings, Hawkins’s practice is aligned by Baker with “the Merz constructions of Kurt Schwitters or the media reconfiguations of surrealism; Joseph Cornell’s memory boxes or Andy Warhol’s time capsules; and perhaps most of all, the excess of West Coast collage and assemblage artists such as Wallace Berman and Bruce Connor.”7

Richard Hawkins, Dragonfly 2, 2009. Oil and pencil on paper, 17 1/4 x 20 1/2 inches. Courtesy of Greene Naftali Gallery, New York.

For Hawkins, collage is not only a method of image building but also an act of object invention. And when negotiating material manipulation and his flirtation with cultural taboos, the results can range from a lifeless parochial exercise to a bewildering relic. Scalps I and Scalps II (both 2010) shred rubber masks into an elongated mass of looping ribbons. The addition of painted color paper scraps clipped to the rubber strands is a hackneyed formal gesture evoking Post-Minimalism anti-form and its erotic demeanor. Also lacking acumen are Dilapidarian Tower (2010) and The Last House (2010), which resemble unimaginative, oversized, and distressed dollhouses. Yet Shinjuku Labyrinth (2007), with its tabletop maze hosting a throng of young, male, Japanese fashion models cut from magazines who are ready to receive you around every corner, is shrewd in its frontal, collage-like riff in real space. This play on flatness and frontality is also at work in Untitled (Taizo in City) (1995), in which a crude tableau comprised of a few commonplace objects and an improvised paper doll are arranged on an impaired folding table.

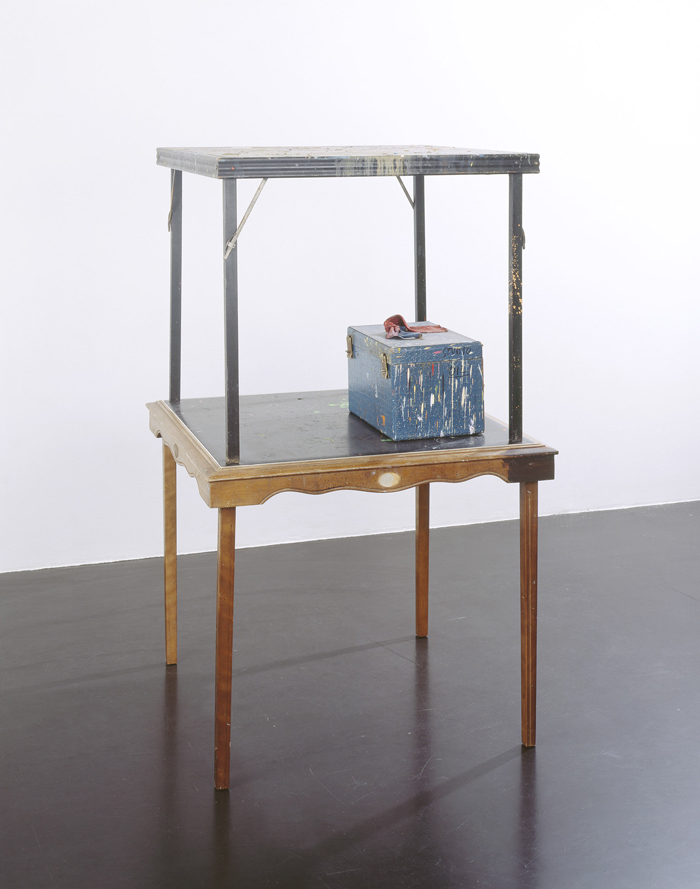

Richard Hawkins, Tomb, 2006. Table sculpture with objects, 150 x 80 x 80 cm. Courtesy of Richard Telles Fine Art, Los Angeles; collection of Kourosh Larizadeh, Los Angeles.

Tomb (2006), the most poetic object in the exhibition, is also the most convincing sculpturally. Two stacked folding tables delineate two elegant volumes of cubic space. The tables, cheap and covered in paint, are corporeal while the cubes of space framed by the table legs are platonic perfection. The surface of the bottom table holds a paint-covered vanity. Like the paint rags in Bad Medicine and Little Pinkfeather, the trappings of a painting studio provide a context for Hawkins’s crafty, self-interested pleasure hunt. Without it we are pulled into a selfcontained world where his lust for young men becomes monotonous and the construction of new fantasies and “expressing differences within culture “8 too familiar. Hawkins is best when collage is more than a medium and more than an organizing system for his obsessions. Tomb does this with emphatic sculptural character, and his ongoing Urbis Paganus series succeeds in developing riveting literary aplomb. Leaving the scissors lying on the table for a while may be just the strategy for Hawkins to further his collage practice.

Michelle Grabner is an artist and writer. She is a professor and chair of the Painting and Drawing Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.