New Red Order, Crimes Against Reality, 2020. Video still. Single-channel video, 10 min.

Like in an old American Western, the Indians line the ridge and raise their fists and whoop. Below, crowded in their summer whites around a wooden stage hung with red, white, and blue bunting, the citizens are helpless against the pending onslaught. They scream and scatter; women lift babes into arms and men pull their hats on tight as they run through the scrub in confusion. It’s no use, they’re surrounded, the Indians charge down from the high ground toward their quarry. Lucky for these civilians, the Jutland police are there. A slapstick roundup ensues as they try to corral the rampaging braves on the slopes. Footage of the event, which was broadcast live to millions, shows officers in absurd crouches, wide-armed, facing off with raiders across a shrub. Dust covers their sharp blue trousers.

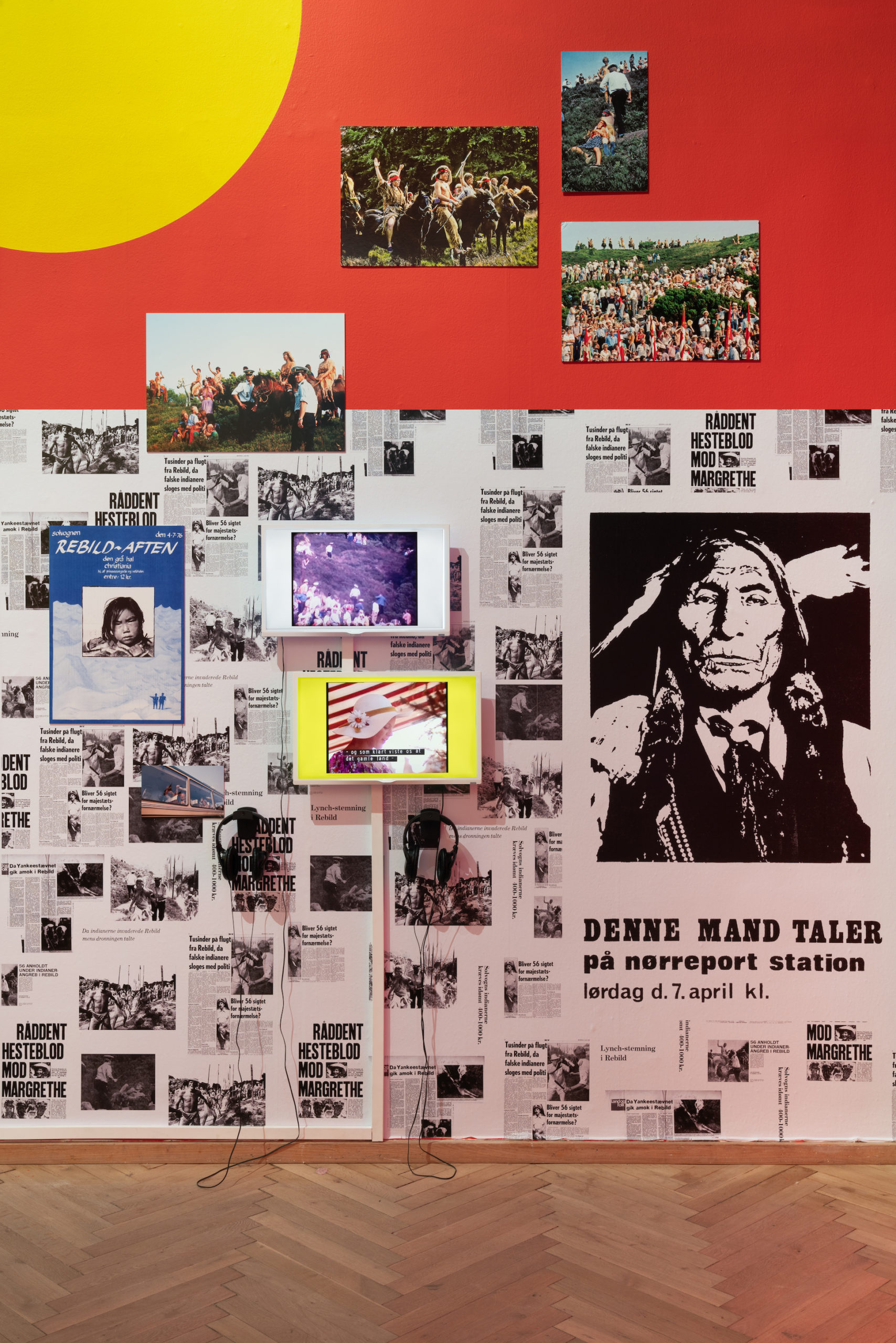

One pageant deserves another. Rebild Action in 1976 was one of the greatest routs in the history of Solvognen, a Danish activist performance troupe.1 A video in New Red Order Presents: One if by Land, Two if by Sea documents the performance, in which Solvognen theatrically terrorized a bicentennial celebration of the United States, held by a mix of expats and Danes on the Fourth of July in the Rebild Hills in Jutland, Denmark. The annual Rebild Celebration has been the largest Independence Day gathering outside of the United States since 1910.2 Solvognen found this uncritical display of transatlantic solidarity in poor taste, and chose to frame this pro-American fest with a reminder of the United States’ foundational genocide. On a nearby wall in the Kunsthal Charlottenborg, another monitor shows clips from 1972’s Wounded Knee, a powwow Solvognen held on the cobblestones of Copenhagen, while across the ocean other activists famously occupied the massacre grounds in South Dakota.

Solvognen, Rebild Action, 1976. Installation view, New Red Order Presents: One if by Land, Two if by Sea, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, March 23–August 7, 2022. Photo: David Stjernholm.

In both cases, Solvognen—who named themselves for the chariot that carries the sun in Norse mythology—donned Indigenous costumes. (For good measure, some performers also dressed as Africans and Inuit peoples.) This was done in stated solidarity with the oppressed, a facet of the globalizing concern for subalterns’ struggles. Rebild Action can be interpreted generously as taking on the burden of filling out the picnicking Danes’ picture: If you want to cosplay as Americans, then you should take the rest of the myth along with it. At the same time, their gesture is a bout of cultural appropriation that, noble intentions aside, mostly serves to assuage white guilt while doing little for the vanquished Indigenous world.

The Solvognen videos appear opposite a dense, curling, and tentacular flowchart on one wall of the many rooms of the Kunsthal Charlottenborg in an exhibition of works by the American art collective New Red Order (NRO) and seventeen other artists and groups. The NRO graphic is often difficult to read; the words slip beyond the grasp of sense and the chronology curls up the wall like a vine to illegible heights. The room is a nightmare version of one of the timeline installations by the New York City-based artists’ collaborative Group Material, for example their AIDS Timeline (1989). NRO applies Group Material’s optimistic, multiculturalist didactics of the nineties to the Danes’ naïve globalism, contextualizing and educating while at the same time letting Solvognen’s bout of red-face hang uncomfortably in the Danish wind. If Group Material’s timeline works draw a straight humanist line through the chaos of cultural history, NRO adopts a weirder model of time, wherein a path spirals through a purple and black field of ephemera and texts, and an organization can claim retroactive ancestry in a way you’re not sure is entirely artistic—or legitimate. The NRO follows a calendar invented by their forebears, a nineteenth-century American fraternal organization called the Improved Order of Red Men, based on what they call the Great Sun of Discovery (GSD). The year Columbus landed in the Bahamas, 1492 CE, is GSD 1. The NRO was founded in 500. The Spirit of ’76? Try the Spirit of 284.

Solvognen, Rebild Action, 1976 and White Man’s Seed, 1975. Installation view, New Red Order Presents: One if by Land, Two if by Sea, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, March 23–August 7, 2022. Photo: David Stjernholm.

Indigenous fantasy is where NRO works. They took their emblem—at least here—from Sherwin-Williams, a bucket of red paint coating the planet in a cartoonish revision of the last 500 years of whitewashing. And here they are in Copenhagen, delivering One if by Land, Two if by Sea explicitly to a Scandinavian audience, maybe even one that considers itself above the racist fray associated with the United States. Does America have a racism problem? Tut tut, it’s the spoils of colonialism. Danes want to be better, to do good. They’ve invited NRO to their capital, haven’t they? But Denmark is also an empire, as we might remember from Trump’s parboiled attempt to buy Greenland. An adjacent wall is given over to Melting Barricades, a 2004 project by Greenlandic and Danish contemporary artists Asmund Havsteen-Mikkelsen and Inuk Silis Høegh, in which they pretended to recruit for a brand-new Greenlandic Army.3 The subtext here, unsubtle for the Danish public, is that Greenland remains a Danish colony in all but name. NRO’s satirical storming of the Danish capitol frames the paradoxes of white allyship for a white and willing audience.

The last room in the U-shaped layout of the kunsthal’s canal-facing wing features a set of informational panels by NRO modeled on the tacky real estate listings mounted in the windows of brokers in places like Park Slope and Aspen. Each sheet has a picture of a different property and includes pertinent information, such as acreage and monetary value. The flyers face the interior of the gallery and are backlit by the wan Danish sun filtered through a nineteenth-century casement. Each sheet represents a plot ceded back to its previous Indigenous caretakers. Some are mini, insignificant: a wooded acre in New Jersey. Others might make a difference: the Yale Union exhibition space in Portland, which recently ended its gallery program and handed the keys to the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation.4 Its flyer reads: “Features: Italian Renaissance revival façade with Egyptian revival details. The water table, seeping through a pit of mud and rubble beneath the catwalk, visibly rises and falls. Parking lot beneath a hollow water tower.”

Asmund Havsteen-Mikkelsen and Inuk Silis Høegh, Melting Barricades (detail), 2004. Installation view, New Red Order Presents: One if by Land, Two if by Sea, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, March 23–August 7, 2022. Photo: David Stjernholm.

It’s an uncomfortable proposal on its face. Just give it back? As in, all of Manhattan? All of the world? NRO insists you’ll feel better. A takeaway leaflet in the style of a real estate ad for New Realty, located on 80 White Street in Tribeca, New York, features a diagram that draws red lines between similar features in a Western-style house and a plains-style teepee—chimneys, windows, doors. Both sit on a six-by-six grid and seem to be of comparable size, except the teepee’s grid spreads out from a point at the top. It’s as if the traditional American house is the teepee, only projected square.5

When I proposed writing about the NRO, a few of my colleagues raised eyebrows— was I, a white man, proposing to write about a satirical Indigenous organization? To what degree was it satirical, really? How offensive should we consider the “red” part in New Red Order? And, most pointedly, were any of the NRO members actually Indigenous? To this last question, the answer is yes—their founders are Ojibwe—but that’s almost beside the point. The NRO casts itself in a lineage of “fraternal organizations” and secret societies comprised of white Indian impersonators with roots stretching back to the Sons of Liberty, who cosplayed as Mohawks at the Boston Tea Party. A nineteenth-century cadre of patriots, the Order of Red Men, fizzled but was rekindled in 1834 as the Improved Order of Red Men (IORM). The latter maintained the “tradition” of feathered headdresses and Indigenous-sounding titles, such as Great Incohonee and Great Keeper of Wampum, but moved their solemn rituals behind closed doors. Both Presidents Roosevelt were members.6 From its seat in Waco, Texas, the IORM boasts fifteen thousand brothers today, much diminished from their peak of half a million. Their website describes their mission as, first, “Love of and respect for the American flag,” and, eighth and last on the list, “Perpetuating the beautiful legends and traditions of a once-vanishing race.”7

The exhibition at the Kunsthal Charlottenborg ends with an invitation from the NRO artists to “Join the New Red Order Today!” Meaning—what? Past a display of NRO merch—lighters, hoodies, balloons, rattles—on a monitor surrounded by standees and backdrops like a booth at a trade fair, the specter of underground theater actor Jim Fletcher appears, his pale skin sickly in a greenscreen’s aura. Fletcher, “award-winning actor and reformed Native American impersonator,” shares his story. “After years of dedicating myself to pushing the limits of artistic expression,” he says, “I did something wrong: I played an Indian. I was mortified, but also confused; how could I reconcile my dedication to art and creativity with these prohibitions on what I should or shouldn’t do?”

New Red Order, Conscientious Conscripture, 2018–ongoing. Installation view, New Red Order Presents: One if by Land, Two if by Sea, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, March 23–August 7, 2022. Photo: David Stjernholm.

The video, a spinoff of a 2019 NRO project called “Join the Informants” for the online journal Triple Canopy,8 picks up the language of liberal guilt and contrition common in artworld circles. “Today, everyone wants a little indigeneity: reporters flocking to pipeline protests, EDM concert attendees wearing feather headdresses, governmental officials performing apologies while maintaining their status as ‘hosts,’ curators extracting relationality, ‘woke’ arts organizations posting land acknowledgments on their websites and advertising shows with images of Native decolonial activists.” Instead, NRO promises cathartic self-help. “The New Red Order will help you take control of your life,” Fletcher says, “enhance and expand your sensitivity to others; and help you learn to identify and transcend your own positionality.” You don’t have to be Indigenous; in fact, while only white men could join its candidly racist predecessors, anyone can (and should) join the New Red Order, a home for “reformed Native American impersonators” like Fletcher.

New Red Order, Conscientious Conscripture, 2018–ongoing. Installation view, New Red Order Presents: One if by Land, Two if by Sea, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, March 23–August 7, 2022. Photo: David Stjernholm.

To whatever degree the NRO is “real”— you can fill out an application through the Triple Canopy project—there’s certainly the potential for a psychic sort of volunteerism: simply acknowledging the harm that Indigenous cosplay causes or, short of that, becoming aware of it and pointing it out. To see alterity through a white mirror. One line of their “manifesto,” on a panel of the timeline in Kunsthal Charlottenborg, reads: “The New Red acknowledges that nobody is a priori White. There are only those who claim whiteness.” Instead of allies, NRO asks for accomplices.

Writing about NRO did lead me to dredge up a—repressed is too strong a word, but—murky childhood memory of participating in the Indian Papoose program at the YMCA, a version of Indian Guides for kids, in which I sewed and decorated my own brown canvas “deerskin” vest with beads and fringe, donned a headband ringed with symbols, and made various arts and crafts from sticks, string, and feathers. The program is largely discontinued, at least with those offensive trappings, but the Y continues to provide camps in the same spirit of outdoor adventure and environmental stewardship—an idealized Indigeneity, re-costumed to good use.

But the road to racism is clearcut with good intentions. One room at Charlottenborg, entered through thick PVC curtains like a meatpacking plant, is lit only in red—red gels on the lights, red film on the windowpanes. A big monitor shows a film by Syilx Nation artist Krista Belle Stewart, Nine ∞, part of a project called Truth to Material (2020–21), in which she turns the tools of anthropology upon so-called Indianers in Europe. Yes, they’re impersonators, too—prime candidates for NRO—although they don’t think of themselves that way. Stewart’s video documents first contact with a German group, decked out in hawk feathers, blood-red rags, and leather loincloths, who erect a teepee village and pay tribute to Indigenous traditions, mimicking Indigenous dress and dance in apparent detail. Unlike Edward Curtis, American photographer of “The Vanishing Race,” these Germans aren’t direct instruments of that disappearance. Instead, in the masqueraders’ minds, they’re preserving a vanishing way of life. They carry on for the Indigenous artist’s camera, even proudly gifting her with an engraved silver bracelet and beaded deerskin dress—both of which she duly puts on display at the kunsthal. In this room, the flooring comes into focus: a collage on vinyl of scenes from anthropological museums, films, and the artist’s documentary work—what the exhibition text memorably calls “instances of questionable homage.”

New Red Order, Crimes Against Reality, 2020. Video still. Single-channel video, sound, 10 min.

Is the answer to the nostalgia for Indigeneity picked up by groups like Solvognen to prove the continuing vitality of First Peoples—to vanquish once and for all the seductive sobriquet “Vanishing Race”? Should the idea of “race” itself vanish? NRO’s answer is to revel in the contradictions and aporias of Indigenous ways in the modern, white world. Fox Maxy’s short film Maat (2020) is one example. This smash-cut montage of video games, found footage, lo-fi effects, and interviews paints a chaotic, unselfconscious picture of Indigenous life. Like the NRO’s reality-bending work, Maat’s images of border patrol mercenaries and dirt roads are a far cry from sand paintings and powwows. The room around Maxy’s film, lit mostly by the glow of its projected images, is full of inflatable pool toys shaped like animals and oases and scattered with balloons. NRO throws an apocalypse party.

Krista Belle Stewart, Truth to Material, 2020-21. Installation view, New Red Order Presents: One if by Land, Two if by Sea, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, March 23–August 7, 2022. Photo: David Stjernholm.

On the one hand, NRO gamely offers salvation through non-Native contrition. On the other, they demonstrate how to live beyond the event horizon of a catastrophe. The Indigenous world has ended—literally, in many cosmologies, and certainly symbolically. Any hint of environmentalism or communalism or sustainability or bravery or resilience or strength or any of the other qualities stereotypically claimed by the Sons of Liberty and their tone-deaf progeny will be needed, and then some, as the seas boil and forests burn and birds fall dead from the sky. Contrite or not, the industrial-colonial forces that vanished the Native Americans are now proceeding to kill humanity wholesale, themselves included. Through a thick curtain and down a dark hall, NRO’s exhibition begins with the most outwardly iconoclastic piece. A widescreen projection on one wall shows 3D scans of certain flashpoint monuments linked to, if not honoring, white supremacy. It includes a copy of The End of the Trail (1928), by James Earle Fraser, which famously imagines a weary warrior on horseback, dragging his spear, and the same sculptor’s Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt (1939), a racist allegory starring a mounted Roosevelt attended by Black and Indigenous men that once introduced the Museum of Natural History in New York.9 Hundreds of photographs of these statues, taken from every angle, flicker on the screen, then seem to coalesce into digital models that animate, grow cancerous, and rot into a kind of pink-skinned, meaty sludge. It’s as if these endocolonial emblems haven’t just been melted down like so much bronze but actually dissolved by enzymes, subsumed by raw biological forces to be reconstituted as something new—or left to pool bloodily on their plinths.

The highway connecting Queens to the Hamptons in Long Island is wild and green, as far as highways go. No billboards are allowed. In 2019, however, the Shinnecock Nation raised the privileged ire of “locals” by building a pair of tall wedges on the highway’s shoulders, six stories high, encrusted with LEDs and brandishing the Shinnecock seal. The Shinnecock planned to lease ad space on the towers (which a New York Times reporter observed are taller than the tree line), nabbing the eyeballs of some of the country’s wealthiest vacationers.10 The fact that the billboards were installed on the tribe’s scrap of sovereign territory didn’t stop NIMBYs from protesting. The town of Southampton, the Department of Transportation, and the State Supreme Court all ordered the construction halted. They were built anyway. Today, says the Times, “A message on the signs welcomes drivers not to the Hamptons, but rather to the Shinnecock Nation.” If this is the end, then welcome to it.

Travis Diehl is Online Editor at X-TRA. This article was supported by a travel grant from the Danish Arts Council.