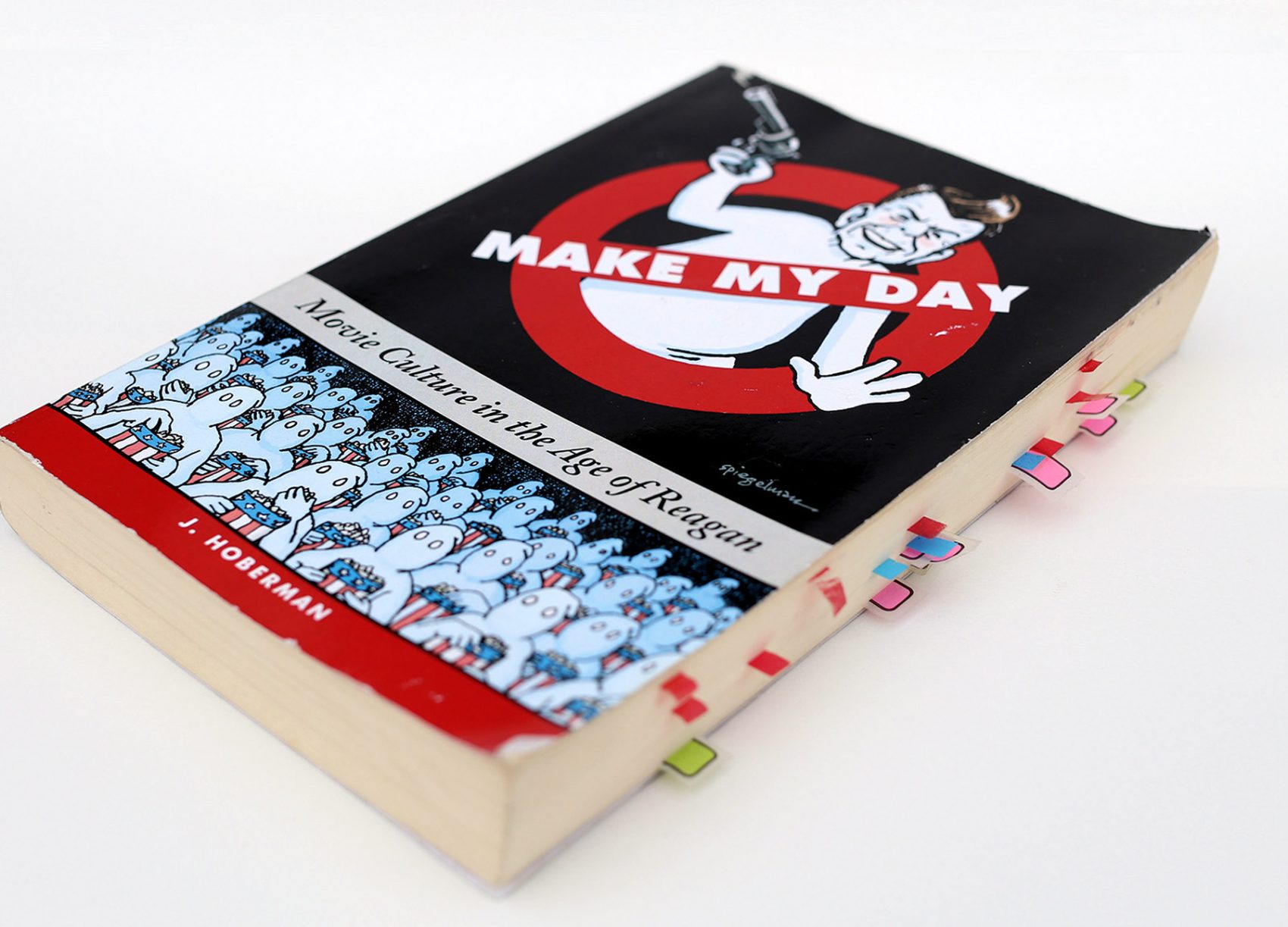

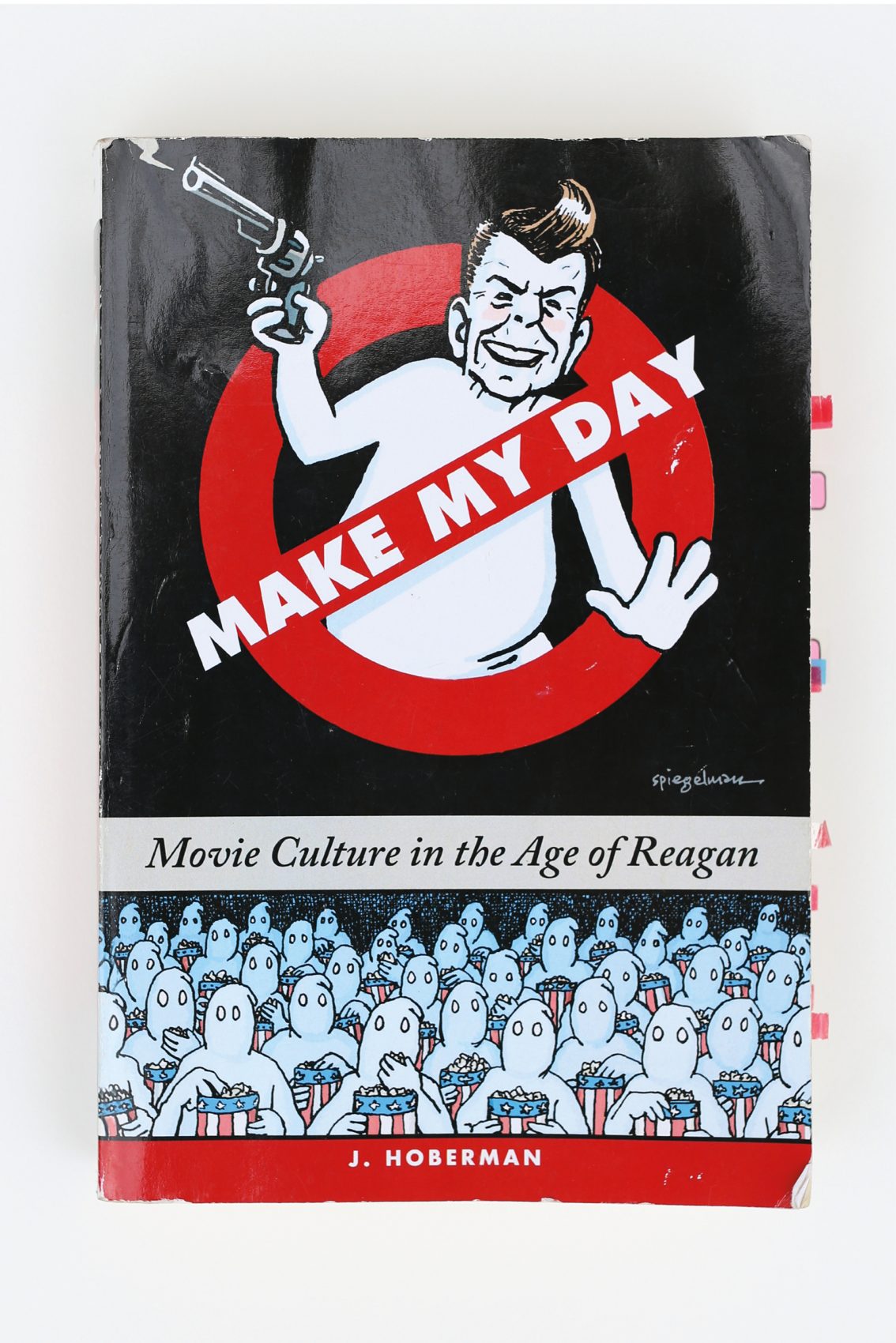

J. Hoberman, Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan, New York: The New Press, 2019. Photo: Poppy Coles.

Nothing is new except what has been forgotten.

–American proverb

This movie begins in flashback. It’s 1968. Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon vie for the Republican nomination for president. Reagan will lose; yet the British novelist J. G. Ballard, observing the Candidate on TV, can’t help but identify a certain viral charisma in the rigid topography of his smile. Imagining the actor-politician compared with Nixon, Kennedy, Johnson, and Hitler in a sadistic clinical trial, Ballard wrote, “Reagan’s face was uniformly perceived as a penile erection.”1 Ballard dresses his prose in a white coat, delegating his own erotic fascination with Reagan to an ostensibly rational process (summarized by an ostensibly rational narrator) that mirrors the focus-grouped plasticity of the actual Candidate, an image of Reagan optimized piece by piece. Yet Ballard titles the story “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan.” It is “I”—not “they” and not “the subject”—that wants to do the deed. Ballard’s short story is an explanation, but the title is a confession that neither the narrator nor the author can analyze away their obsession.

Ballard’s fantastical account of Reagan’s turgid appeal also turned out to be accurate, and is credited with foreshadowing—cynically, ambivalently, scientifically—the made-for-TV magnetism that the Candidate would ride to his eventual triumph in 1980. It did nothing to counter Reagan’s rise. Indeed, as Ballard himself notes, when a group of “pranksters” distributed copies of this text at the 1980 Republican National Convention, without Ballard’s title and with the addition of the Republican seal, it was taken “for what it resembled, a psychological position paper on the candidate’s subliminal appeal, commissioned from some maverick think tank.”2 Mark Fisher, pointing to the same episode, writes that “this neo-Dadaist act” can be “hailed as the perfect act of subversion,” while at the same time, “it shows that subversion is impossible now.”3

Perhaps this sense of resignation is why Fisher titles his reading of Ballard’s story after Ballard’s: “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan.” The critic’s distance has collapsed: here, too—and in a more direct sense than in Ballard’s story, since Fisher is writing in his own voice on his blog—that “I” puts the author’s distance from his subject into question. This congruence finally erodes the boundaries of the critical act. In the final draft, the “I” of both authors abandons the pretext of their jargon—the technical tone of Ballard’s story and the intellectual address of Fisher’s column. Neither author wants to “fellate” or “engage in sexual intercourse with” the Candidate; they want to “fuck.”

Ballard’s story’s impotence as a work of satire arises, Fisher writes, because “what Ballard’s text ‘lacks’ is any clear designs on the reader, any of [Fredric] Jameson’s ‘ulterior motives’; the parodic text always gave central importance to the parodist behind it, his implicit but flagged attitudes and opinions, but ‘Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan’ is as coldly anonymous as the texts it imitates.”4 This is true of the text itself, nested within the reliable voice of reason. Yet Fisher overlooks precisely what the pranksters wisely excised from their convention handout. The key to Ballard’s story is the precarious coexistence of the “coldly anonymous” body of the text with its hotly desirous title. It is this desire, this first intellectual pique, that leads the critic to engage his subject in a way deep enough to, later and in another context, pass as objective. The subtext is that this total incorporation of the possibility of satire within its would-be target is the fallout of a seduction. The critic, satirist, and skeptic finds himself, however knowingly or reluctantly, drawn to the dominion of Reagan’s erotics over facts and their logical deployment—deconstruction, postmodernism, and the critical faculty. And the more thorough the critic’s analysis, the more it performs the balanced work of a market study. The critic workshops the flaws in the product—the Candidate—and helps his team write an alternate ending.

J. Hoberman spent the Reagan years reviewing movies for The Village Voice. For Hoberman, the Candidate’s presidency consummated the confluence of politics and culture that today feels self-evident. Wading into this unctuous politics, Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan, published in 2019, is the third and final book in Hoberman’s Found Illusions trilogy. All three books have Reagan as their antagonist—in the 1950s, as an instrument of the Hollywood nostalgia on which he would later base his brand (An Army of Phantoms: American Movies and the Making of the Cold War [2011]); in the 1960s, as the anti-counterculture governor of countercultural California (The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties [2005]); and, finally, in the 1980s, as the figurehead of fantasy’s coup. Hoberman’s effort follows the idea that, where art informs the culture that informs politics, art criticism is a direct form of political critique. His writing on film considers art as a constituent factor of the culture that precedes politics, instead of treating art as a straw man for politics. After all, the president and his country watch the same films—a fact Hoberman details by mining Reagan’s diaries and White House guest lists for records of private screenings in Washington and Camp David. The Reagan presidency teed this up nicely, too. As Hoberman wrote in 1989, eulogizing the Candidate’s reign, “Reagan reminded us that we are the movie the whole world watches.”5 The film critic found himself cast by a filmic president in the role of a politico.

Hoberman retells this national history his way, movie by movie. Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983) gives Reagan the language to advertise the Strategic Defense Initiative—Star Wars—and to invoke the Force. Ghostbusters (1984) coincides with the United States conquest of Grenada; Hoberman sees both events as feel-good productions meant to exorcise Vietnam’s lingering ghosts. “Over eight thousand medals were given out,” the critic writes, “to commemorate what the Washington Post hailed as ‘the most popular invasion since E.T.’”6 Two years later, as the Iran-Contra scandal deepens, Platoon (1986) again attempts to catharize the psychic quagmire of the Vietnam War. It was as if Hollywood itself had become president.

The Reaganist ideal is best described as it portrayed itself: the America of 1950s Hollywood. And, like a sententious film, Reagan could mean whatever his public wanted him to mean. Hoberman’s main obstacle in undertaking any kind of critical history of film in the age of Reagan is that many of his connections will have been drawn, preemptively, by Reagan himself. Again, Ballard thematized and foresaw Reagan’s appeal back in 1968, as it was still being assembled: “Fragments of Reagan’s cinetized postures were used in the construction of model psychodramas in which the Reagan-figure played the role of husband, doctor, insurance salesman, marriage counselor, etc.”—the archetypes of grayscale suburbia.7 Yet these “cinetized postures,” from which you may take your pick, are slick, not sticky. “The failure of these roles to express any meaning reveals the nonfunctional character of Reagan. . . . Reagan thus appears as a series of posture concepts, basic equations which reformulate the roles of aggression and anality.”8 Hoberman describes how Reagan’s buffoonery, his public face, and his flights of fancy are calibrated to distract and to fascinate. Parody is impossible: one can hardly nail a president for selling thin fantasies when he himself compares politics to acting.

“Facts are stupid things,” Hoberman quotes Reagan saying.9 In Make My Day, the facts come together with a conspiratorial click. In the first sentence of the first paragraph of the introduction, Hoberman observes the facts that Reagan was shot on the afternoon of the fifty-third Academy Awards ceremony and his would-be assassin, John Hinckley Jr., drew his inspiration from the 1976 Martin Scorsese film Taxi Driver. (Hinckley also stalked Taxi Driver actor Jodie Foster.) Hoberman notes that, after the shooting, the awards were postponed for one day. The next evening, Reagan viewed the program from his hospital bed. It was there, presumably, with the flags at half mast, that Reagan watched as “a screen descended on the stage” and his own face began to speak. Hoberman writes that Reagan’s praise of Hollywood, which was prerecorded weeks before, “came an inch from being delivered beyond the grave.”10 All this in Reagan’s first one hundred days in office.

Reagan was a high-budget put-on. He even believed his own lies. Against Reagan’s pragmatic mysticism, Hoberman’s analysis is historical. Where the critic cannot puncture the Candidate’s beaming image, he can ground it—weigh it down with context. He builds an edifice of facts that, he hopes, can withstand wave upon wave of Reaganist (or Trumpist) denial. In Make My Day, Hoberman records the fact that, having been deeply affected by footage of the Holocaust, Reagan bragged to Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir that he had personally shot newsreel of GIs liberating a concentration camp. But Reagan was in the signal corps—in Hollywood—for the duration of the war.11 As is often the case with Reagan, belief creates its reality, not the reverse. Hoberman reminds us that Reagan reserved a special fascination for the Shroud of Turin, writing in his diary that he was “convinced it is the burial cloth of Jesus and it certainly gives credence to the bodily ascension.”12 He offers this detail as evidence of Reagan’s faith-based deliberations and his outright superstitious reliance on the difference between good and evil. Hoberman’s example is telling for another reason, only hinted at in the text. Both the Shroud and the Hollywood movie rely on the promise of the index for their realism: the impression has been made directly by the physical form of a body, and yet the image is the result of no human hand. Film, like the Shroud, is miraculous and therefore proof of the miraculous organization of reality by fantasy (and not the reverse). And so, when Reagan was shot, the stricken president prayed to God for the strength to keep up the act. (Hoberman rates his hospital stay a “bravura performance.”13) Meanwhile, Nancy Reagan consulted her personal astrologer.

Registering a more personal history, Hoberman’s book incorporates a handful of the author’s own contemporaneous writings on film and Reagan, such as the piece he published in 1985 on the occasion of the Candidate’s reelection, “Stars & Hype Forever.”14 What he identified then remains true today: the sympathetic theme of Hollywood’s and Washington’s big tickets—the rebirth of America into a forgetful new day. In Hoberman’s analysis, the movie E.T. (1982) carries the “promise of rebirth and celebration of innocence”; Indiana Jones (1981) thrills through “shameless woggerry and utter bimbosity” (i.e. sexism, racism, and orientalism are fun again); and Red Dawn (1984) refracts the Cold War into a “bellicose fear of a Nicaraguan invasion and chipper denial of nuclear war.”15 Of Ghostbusters, Hoberman need only note that the Wall Street Journal praised its depiction of free enterprise. Insofar as this accounting of history resists a politicized cultural amnesia, the critic’s role is clear and important. It is strategic accumulation, movie after movie (film after film).

J. Hoberman, Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan, New York: The New Press, 2019. Photo: Poppy Coles.

Hoberman ends the 1985 piece—and ushers in the Candidate’s second term—with a song: Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” (1984), a top-forty hit “whose bizarre religious overtones are paralleled by its singer’s nom de pop.”16 The song, he writes, is like Reagan himself, “at once prurient and puritanical.” And this contradiction extends to the way Reaganist rhetoric could sell nostalgia without the dust, a return to a past so clean and idyllic it had never been used before. “Yeah, Ronald Reagan made us feel ‘shiny and new’ all right,” Hoberman wrote, “the better to fuck us again.”17 The sexual tenor of this conclusion is no accident. Neither is the association of sex and forgetfulness. Nostalgia is absent from Ballard’s “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan.” He portrays intercourse as a matter of selection between options, like answering a poll, and sex passes into the neoconservative frame of Reaganist nostalgia as a factor of the cold, pragmatic ideology that repeatedly put forth the Candidate.

The movies are the screen with consequences—the simulacrum that shapes the life of the country that shapes the world. Hoberman gives the example of The Last Picture Show, a 1971 film meant to pay tribute to the cinema of the 1950s and which “the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard claims to have momentarily mistaken for the real thing.”18 Like supermarket magazines hawking the “Best Movies of 1984,” Hoberman’s book pays tribute to a sophisticated nostalgia machine. He folds history along certain decades, illustrating the latent congruence between how the 1950s looked through Reagan’s eyes in the 1980s, and how, today, the 1980s look through Trump’s. It is not a rosy picture. In a Rolling Stone interview, Hoberman points out that the biggest movie at the box office during the summer of 1982, when the now Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh likely committed sexual assault in a friend’s bedroom, was none other than Conan the Barbarian. The movie starred, it bears recalling, Arnold Schwarzenegger, who would soon reprise Reagan’s role as governor of California.19 The facts implode into the image of Kavanaugh lifting weights with Squee, his adolescent brain piqued with visions of what Hoberman writes is the first of the “hard body” action heroes.20 The brutality of American culture, asserts Hoberman, inevitably feeds its brutal politics.

On this point, too, the critic allows himself to be seduced; his obsession takes on the clinical character of cause and effect. It is “justified” by all kinds of technical output: forms, articles, rationale, surveys, and principles—Ballard’s jargon or Baudrillard’s—as if we are all blameless victims of our film-induced impulses. And with this belief comes a certain romantic misapprehension of what criticism in the 1980s mode accomplished. See the tragic heroism of Wayne Barrett, a colleague of Hoberman’s at The Village Voice. He reported on Trump for decades, shining a harsh light into the dark corners of his playboy act, yet was unable to avert his rise. Barrett died the day before Trump’s inauguration.21 The Candidate could cut through the critic with a word, just as he dispatched Carter: “There you go again.”

The fortunate critic has an audience of hundreds; a middling politician, millions. Movie culture reaches billions. Hoberman has hit on the strategy of amplifying cultural criticism through the current events of the rich and powerful. Make My Day, in some sense, has the idealistic sweep of pop analysis that treats journalistic photos as art history. Yet such photos can only follow politics, while movies help create it. Hoberman describes films in the course of a cultural postmortem, analyzing events alongside contemporaneous movies and presenting them as parallel helixes of the dominant history. The waves of public interest build and crest and break, like blockbusters, in tight sets. To ride them into public discourse, let alone the cultural imaginary, is a feat worthy of a Hollywood president. Reagan is dead, of course. But his epilogue, like that of Hoberman’s book, consists of one all too obvious fact: this has all been a prequel, and the dream has been rebooted with a different throwback cast.

Travis Diehl is Online Editor at X-TRA. He is a recipient of the Creative Capital / Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant and a winner of the Rabkin Prize in Visual Art Journalism. He lives in Los Angeles.