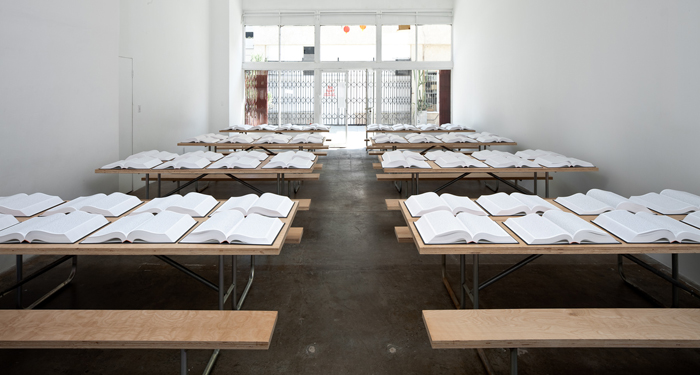

War is a speech act. There may be fighting, there may be battles, bodies tossed on top of bodies and men made stem-less with the careless disregard of daisies reaped by little girls. But large-scale killing is not war without the rhetorical gesture: war is war only because we say so. In Rachel Khedoori’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, she enacts the speech act of our most recent war, that abrupt point at which it began as a declaration and the monotone pointlessness of its continuing articulation. Untitled (Iraq Book Project) (2009) is a collection of news articles beginning with the start of the Iraq War on March 18, 2003, culled via search engine, which finds items with the words “Iraq,” “Iraqi” or “Baghdad” in the title.* The articles, taken from international news sources, are ordered chronologically, formatted uniformly, and translated into English. The only distinguishing aspect between entries is a boldface title, date, and source text. The hardback volumes, displayed serially on long, plain, pine-colored tables with benches, are the size of unabridged dictionaries, with gunmetal grey cloth covers and thick white paper. There are currently 66 volumes, covering the years 2003 to 2008, though the compilation continues during gallery hours. Like the war it chronicles, the project goes on with no fixed termination, although the President, unlike the artist, promises to end operations in 2011.

Khedoori’s appreciation of the materiality of her text is complete. She uses a typeface that features serifs, which tend to indicate authority. But the font is Courier, the font used by the screenplay–the language of American cultural imperialism–not, as one might expect, the more overt empire-authority of The Times’ Times New Roman. The broad whiteness of the pages discourages casual thumbing, as befits a sacred, or pure, text. The books themselves are too large to be held while reading, and their sheer mass guarantees they will not be read, at least never completely. The gallery press release characterizes the work as sculptural. It is that, for it uses the spatial manifestation of time in the same manner as Hanna Darboven’s great indexical projects, such as Evolution Leibniz 1986, an installation of a year’s worth of “a day’s accounting” composed of 444 double-spread pages, vertically mounted and framed, which was also designed to function horizontally as a book.

Rachel Khedoori, Untitled (Iraq Book Project), 2009. 66 books, 9 wooden tables; dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Box Gallery. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

However, Khedoori’s project is moreover archival in the very best non-sense of the word. In The Archaeology of Knowledge, Foucault calls “archive” that which acts as a system for the formation and transformation of statements. Statements, in turn, are enunciations, not containers of content, but language events–the foundational language event similar to that of the subject: I am because I say “I.” The archive has meaning mostly because it is. Like bodies on the battlefield, it is language or text as such that counts (quantity), not the relative merits of its pronouncement (quality). For any appreciation of the sheer materiality of Khedoori’s texts must also include an appreciation of their equally fraught immateriality.

Lucy Lippard famously identified 1966 to 1972 as the period in which the art objectwas first dematerialized; in economics, dematerialization has become a fundamental principle of sustainability–“to do more with less.” To win wars, the military uses material, but the material of war is, as noted, textual. And the textual correlative to the dematerialization of the art object is immaterialization. Immaterialitywhich maintains its material status, i.e., immateriality as in textual irrelevancy, as in that which is beside the purported point of a specific text object. (That there are no images in Khedoori’s books recalls Susan Sontag’s argument in Regarding the Pain of Others that images of war require language in order to have meaning: the only difference between a photo of an atrocity and a photo of a victory is the caption.) One of the tenets of literary conceptualism is that we are glutted with excess text. Regardless of the importance of the material, it is simply material. In this sense, Khedoori’s project is in sympathy with Kenneth Goldsmith’s book Day (2003), a retyping/reformatting of a single day’s edition of the New York Times, or to my own Statement of Facts (2009), which is a self-appropriation of statements of facts in criminal appellate briefs, narrative accounts of what may or may not have happened to constitute a crime, written by me in my work defending sex offenders. News comes at us on a daily basis because it is (at best) what is considered important at the moment, and because it is (at worst) the propaganda of the moment. By capturing the transience and flickering subjectivity of the moment-by- moment and setting it in the textual equivalent of stone, Khedoori re-enacts how it is that only some of the news is caught and re-formatted into history books, while other news remains just yesterday’s news.

By translating the articles into English, Khedoori underscores the materiality of English as the global language. The British Council notes: “English is the main language of books, newspapers, airports and air-traffic control, international business and academic conferences, science, technology, diplomacy, sport, international competitions, pop music and advertising.” Eighty percent of electronically stored information is in English; eighty percent of Internet communications are in English; more than two-thirds of scientists read English. English, of course, meaning American. As Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries pointed out in a paper presented at a 2008 CalArts conference on extra-textual writing, it’s not the meaning of the English used by Koreans that matters, but the American-ness of matter in English. In other words, anything in English signifies that which is “American,” even beyond the United States as a country, or America as a geography. The signifier in this sense exceeds and eclipses the signified. At a party recently, someone challenged me on America’s linguistic domination, comparing English to Latin, and predicting its similar demise. But the fact that the rise of empires predates their fall doesn’t change the other fact that a large span of temporal-spatial geography was written in Latin because Rome was home to all the major victors, and victors, as everyone knows, are the first to write history, which is how History is made. And as Khedoori’s project also evidences, history is histoire, which in French means history and story, and, of course, bullshit. For there is something deeply bullshit within this project. Not in the project itself, for the work does elegantly what excellent conceptual work ought to do: create the self-perpetuating machine of its creation, and propel an aesthetic and ethical encounter of a very high order.

Rachel Khedoori, Untitled (Iraq Book Project) (detail), 2009. 66 books, 9 wooden tables; dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Box Gallery. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

But bullshit nonetheless. Because what I should have said before is that you could read the pieces, but you won’t, like I didn’t. For old war news is no news, as quietly monotone as Normandy tombstones. We like our history cold and concentrated, already put into books, as this better suits our prefabbed sense of a readymade historical self. The bullshitty part here is that we are watching contingency being openly shunted into history, without even the usual pretense of metaphysical picking and choosing. In other words, by using a search engine as the archival hand, Khedoori gives the lie and the finger to any evolutionary notion of temporal progress, to the (arguably necessary) cultural myths that things turn out the way they do in service of some larger common narrative, that news must be reported, and that wars are fought in the grand name of History, when the truth is that it’s all so much sausage. By its blunt and relentless manufacture, Untitled (Iraqi Book Project) is as brutal a confrontation with the contingency of fate as a meat-processing plant. This war, Khedoori suggests, is nothing more than a war of wordcraft, and no less deadly for it.

Vanessa Place is a writer, a lawyer, and co-director of Les Figues Press.

* The other piece in the show, cave model (2009), is, according to the gallery’s description, “a small-scale representation of a primitive living space.” While it does have the aspect of a warren, conveniently cut away for viewing, it also feels like radically opened bowels, or tripe, cleaned for cooking. The piece has been squirreled in the nether regions of the space, lending a nice Cartesian body/ soul divide to the two works.