The following conversation between Alice Wang and Shirley Tse took place over Zoom on December 29, 2022. It has been edited for length and clarity.

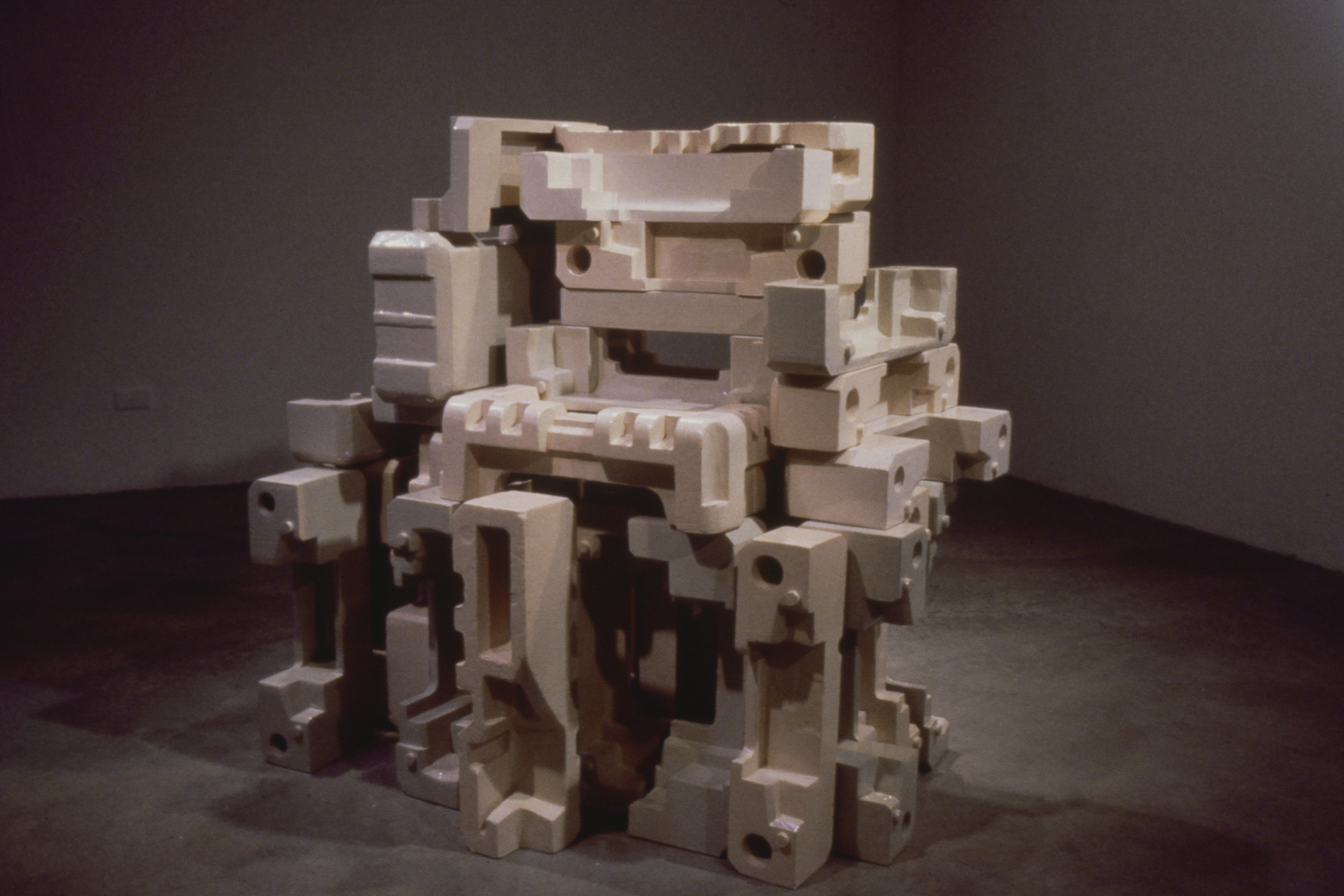

ALICE WANG: In a review of the group exhibition Bastards of Modernity at Angles Gallery in 1997, Bruce Hainley wrote about your sculpture Untitled (1996), which he described as “beige and gray vinyl upholstering of audio-equipment packing Styrofoam.” He observed: “In her modular accumulated sculpture, the Styrofoam’s holes and cutout nooks comment on the usefulness of the seemingly useless—the holes are cost-effective because they make the package that much lighter to ship—and their formal oddness becomes visible.”

From Untitled to your exhibition Stakeholders, which represented Hong Kong at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019, modular accumulation and formal oddity are reoccurring qualities in your work.

Shirley Tse, Negotiated Differences, 2019. Wood, 3D prints with wood, metal, and plastic filament, dimensions variable. Installation views, 58th Venice Biennale, May 11, 2019–November 24, 2019. Collection of M+ Hong Kong. Photo: Ela Bialkowska.

SHIRLEY TSE: Untitled is made of discarded Styrofoam blocks—packaging polystyrene that I found while dumpster diving. I then used three different kinds of vinyl to cover the Styrofoam surfaces. It was very labor-intensive to make. I traced all of the facets of each block down to the insides of the holes, made templates, and then cut them out in vinyl. I used a spray adhesive to glue the vinyl to the surface of the block. Everything needed to be exact, otherwise, the Styrofoam would show through the seams. The blocks are stacked into a form that is about 48 inches tall by 40 inches wide by 48 inches deep, more or less the volume of a pallet of goods.

Shirley Tse, Untitled, 1996. Vinyl, found Styrofoam, installation dimensions variable.

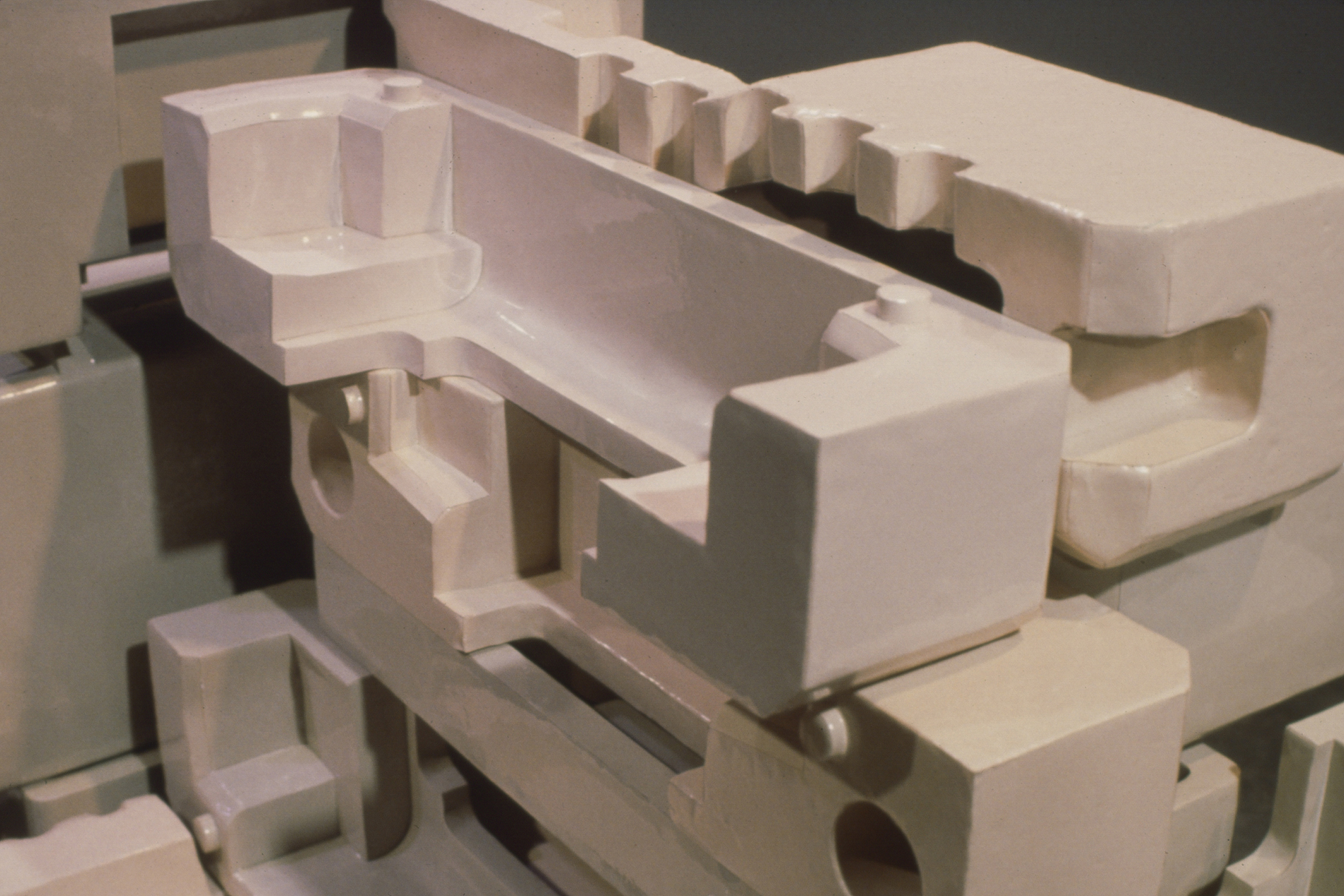

Modularity does recur in my work, including in Negotiated Differences (2019–20), which I made for the Venice Biennale. But, when you examine the modular units in the later work, it is very important to me that each node is completely different from the next. For the Venice piece, people compared it to LEGO blocks. I would say it is like LEGOs, except that LEGO pieces are uniform and identical. My sculpture pieces are not. Each piece is different.

The thought form of Negotiated Differences is a precarious balance of all kinds of differences coming together through the negotiation of weight, angle, color, shape, and implied function as mediated by gravity.1 It is not the negotiation of differences. It is a way of qualifying differences as immanent, not transcendental. Differences are not defined by a fixed identity or category externally but are experienced through the act of being with others, which shifts in each negotiation because it is always relational.

I think the installation invites multiple interpretations, one of which is a metaphor for human relations. It also models the way I perceive sculptural objects. You can objectively describe this spindle as a four-foot, five-pound piece of orange Padauk wood in the shape of a table leg. But how this spindle is different—and in what ways it is different—from the one next to it depends on the particular dynamic at play in a specific part of the installation, for example, whether the spindle is performing physically as a counterweight, formally as color, or symbolically in a particular read of its function. And that very same spindle may be perceived very differently in a different configuration in the next iteration of the installation. I never see objects as isolated or definitive; they are always relational and in a realm of performativity when they intersect with human subjectivity.

Shirley Tse, Negotiated Differences (detail), 2019. Wood, 3D prints with wood, metal and plastic filament, dimensions variable. 58th Venice Biennale, May 11, 2019–November 24, 2019. Collection of M+ Hong Kong. Photo: Ela Bialkowska.

WANG: Could you speak more to the distinction between immanence versus transcendence in qualifying differences?

TSE: When X is different than Y, X experiences and understands this difference immanently through negotiations and interaction with Y. A transcendental difference is when there is a third party, a metaphysical being or an omnipresent narrator, who deems X and Y different, usually through labeling.

WANG: Are the modular pieces from Untitled (1996) and Negotiated Differences stuck together, or are they loose?

TSE: The pieces from Untitled (1996) are stacked on top of each other, there is no glue. Because they are made with vinyl, a plastic surface, when they are stacked, they have friction and some stability. Likewise, no glue or nails are used in Negotiated Differences. The turned spindles are linked through pressed fits of 3D-printed connectors.2

I think the 1996 piece was in my thesis show [at Art Center College of Design]. At that time, I was thinking a lot about formal quality or the formal outcome of something: How does one arrive at a certain form, a configuration? In grad school, I reexamined what constitutes a formal decision and what makes something good or bad. I discovered that formal decisions are oftentimes the convergence of different things, they are not singular events. It’s not just your own personal preference or your taste, it’s a learned aesthetic; it’s the environment around you that you have internalized. All these things come together to produce a certain kind of formal outcome. Although I am interested in Minimalism, upon reflection, it has occurred to me that my interest in modularity and industrial materials did not come from art history. It came from the observation of my daily landscape. As a teenager, I lived near the container terminal in Hong Kong. The whole terminal was lit up at night, and it was fully automated. All I saw were container boxes being stacked at the port. That had more of an impact on me than art history.

I was drawn to Styrofoam blocks because their form was a mystery to me. One would think they are the negative form that fits into the positive form of computers and other electronics. But I took a closer look at them, and I realized there were negative forms in these blocks that did not correspond to any positive form of the products they protected. After doing some research, I found out some negative areas do not correlate to the shape of the products. The hollow areas in the corners, for example, are there to save on the material cost of polystyrene, and the protruding buttons and their corresponding cavities allow for ease of stacking before they are deployed as cushions. The formal outcome of this object, which is a product of industrial design, is a convergence of cushioning, cost, and transportation. In other words, what I learned was that abstract forms become more interesting when non-formal decisions are involved. By the time I made Negotiated Differences, I was convinced that all physical forms are the visual ciphers of relations. I hadn’t read any Doreen Massey prior to the exhibition, but the Hong Kong urbanist and artist Sampson Wong told me that Negotiated Differences evokes Doreen Massey’s idea of “the geometry of power.” That seems quite apt.

Shirley Tse, Untitled (detail), 1996. Vinyl, found Styrofoam, installation dimensions variable.

WANG: The sense of vulnerability in the way the modular units are accumulated in your work reminds me of the precarity of our postindustrial present. If someone accidentally bumped into the stacked forms, the entire thing would collapse.

Rather than an overdetermining operation that is planned out ahead of time, your creative process seems guided by a whimsical and idiosyncratic logic. A kind of poetic and improvisational quality is also evident in the imperfections that result from the laborious processes of cutting and pasting by hand and in the final arrangement of the stacked forms. This makes me think of your photographic work from the late 1990s to 2000, which I understand you consider to be sculptural.

TSE: Vagabond or Wanderlust? (1998) was the earliest of those works, and it was made in Death Valley. This piece came from the sculpture She’s Got That Air (1997), a room-sized, floor-to-ceiling piece made of trash bags that I blew air into and sealed with a heat sealer to form cube clusters. That was for a show at LACE [Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions]. I knew it was going to deflate throughout the duration of the exhibition, and that was part of the point. This has a relationship to the last thing you said, about precariousness. And, I think it has a lot to do with change and the idea of shifting states. Whether it is composed of modular pieces, which suggest the possibility of different permutations, or loose parts, such as long strands, tubes, chains, ties, or unsewn sheets, my work always implies shifts or literally shifts (much to the chagrin of my galleries and collectors). There is no fixed state. That is part of my sculptural language.

Shirley Tse, Not Exactly A…Series #1, 1998. Ilfochrome mounted to aluminum, edition of 3, 20 × 30 in.

I had an idea that, after the show at LACE, the piece needed to simply go into the landscape to be released, to be with the wind. There’s something about the equilibrium between the air inside the works and the air outside; I needed to introduce the wind into the work. I cut it up into three pieces and, on a camping trip to Death Valley, I placed them into the landscape and photographed them. But of course, I did not leave them there; I collected them afterward.

WANG: Mark Godfrey wrote of these works: “I’d like to imagine . . . that Tse is on a strange quest to find out where these pink and blue bodies can be at home, and, ironically, that may be where they would seem most out of place. If in cities plastic is so ubiquitous as to be invisible, when caught by the camera in the great outdoors it can appear surprising once again; it can breathe.”3 The afterlife of this work speaks to the idea that you didn’t have a specific outcome in mind; it was motivated by a desire for homeostasis—to free the work in the desert for a moment.

In an artist lecture at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, you talked about “the site of sculpture,” whether it is physical, social, or political. When you removed the sculpture from the white cube at LACE and recontextualized it in the desert landscape through the photographic process, something else emerged.

Following this line of inquiry, we’ve hit on a core theme that runs through your practice: plasticity. In the earlier years you were using plastic exclusively as a material. The idea of plasticity eventually took on a life of its own. Your work operates in a way that is mutable and difficult to pin down; your sculptural language is flexible, embodying multiple perspectives and, going back to your earlier comment, shifting states.

Also, it seems to me that the aggregate format is part of your visual vocabulary, from the modular Styrofoam stacks of Untitled (1996) to the discrete wooden objects of Negotiated Differences, which are fitted together using friction. Modular accumulation allows space for improvisation and play. It is also marked by the index of your hand and the personal narrative that surrounds the making of the work. I remember hearing that one of the wooden objects in Negotiated Differences was inspired by Nancy Pelosi’s gavel.

TSE: In Negotiated Differences, I wanted to encompass as many differences as possible. I purposely did not want to have everything predetermined, so spontaneity and improvisation are indeed important. I had a mental check-list of the things that I needed to have, and then I allowed my daily visual landscape to enter into the work. I researched the variety of wooden objects that have been produced on a lathe in both ancient and modern times and across the globe. I would turn one object and then proceed to another, until I had a broad range: musical instruments, sports equipment, kitchen utensils, domestic objects, outdoor objects, abstract marks, representational shapes, art historical markers, something feminine, something masculine, Chinese furniture, Moroccan balusters, carvings that show practice runs as well as carving that shows a mastery of woodworking skills. What actually happened is, again, the narrative of my visual diary. That day in 2018 when the Democratic party won back the House, Nancy Pelosi was on TV holding a gavel. I didn’t even see Pelosi’s face, all I could see was the wooden object that she was holding in her hands. I thought to myself, “Oh, my God! That’s made of wood! I think I can carve that tomorrow.”

I think the idiosyncratic quality that you discern in the work comes from that space. It has an overall structure, but then I also allow space for the non-programmatic, for it to unfold itself, so to speak. Also, this no-glue and no hidden armature principle is perhaps a kind of modernist move of “truth to material.” There is no deceit. Everything is laid bare for the viewer to experience: there are infinite permutations of components and connecting angles, and gravity becomes palpable.

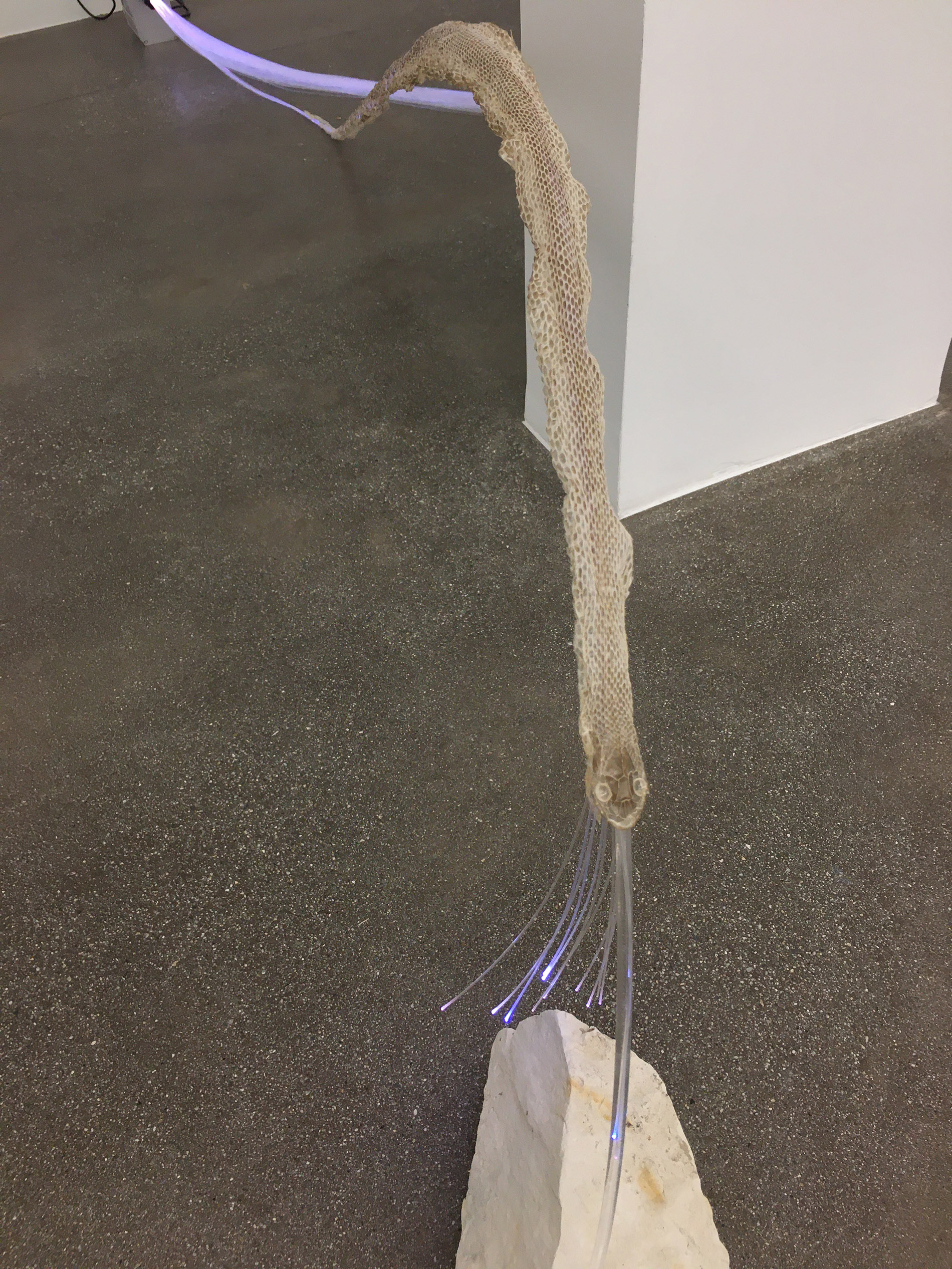

Shirley Tse, Lompoc Stories: Spacesuit, 2021. Found snake molt, fiber optics, diatomite, installation dimensions variable. Installation view, Lompoc Stories, Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Los Angeles, California, June 18–July 30, 2022. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery.

WANG: Your work at the Venice Biennale also included the outdoor installation Playcourt (2019), which has bleachers that allow spectators to sit and view a sculptural representation of a badminton game while listening to amateur radio transmissions.

TSE: In Playcourt, sculptures mounted on tall tripods and functioning amateur radio antennas direct the viewers’ sightlines skyward. At that height, laundry lines across the courtyard enter the visual field. I wanted to emphasize that the Hong Kong pavilion occupies a domestic residential space. It’s not a neutral exhibition site. People actually live above the venue. The title of the exhibition was Stakeholders, and I wanted to evoke two different realms of reclaiming the public domain—street badminton in the publicly shared physical space and amateur radio communication in the publicly shared airwaves.

When I played street badminton with my siblings in my childhood in Hong Kong, we didn’t use a net. We used make-shift materials, like trash cans. I thought it would be absurd to play badminton over a line of very delicate sculptures. On top of that, the shuttlecock is made of cast rubber and vanilla bean pods. These materials—absurd for a birdie—are colonial trade products that allude to the colonial history of Hong Kong. The shuttlecock also visually suggests the back-and-forth movement of rubber and vanilla, quite like the trade routes between Asia and Europe and the Americas on a map. Allowing viewers to sit on the bleachers offers them the vantage point to imagine the trajectory of movement and have the temporal experience of listening to amateur radio operators’ dialogue.

WANG: In your new work in Lompoc Stories, from your show at Shoshona Wayne in the summer of 2022, the materials you chose to work with convey a sense of openness, freedom, and lightness. The sculptures felt like haikus. Could you speak to the playful and poetic qualities of the new work?

Lompoc Stories, installation view, Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Los Angeles, California, June 18-July 20, 2022. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery.

TSE: Lompoc Stories is a collection of distinct pieces. There is sparseness (such as an imageless video), poetic juxtaposition, and humor. I think that explains some of the haiku qualities that you discerned.

As a collection, it does follow some parameters. My recent and current work is primarily the contemplation of sustainability: How do I maintain a sculptural practice that is sustainable ecologically, financially, and health-wise? I set up some limits for the production of this exhibition. To minimize my role as a consumer, I wouldn’t allow any new store-bought materials, only found things and materials I already had in the studio.

I think seeing limitation as a game makes it more whimsical. If I don’t allow myself to go to the store and buy part A and part B polyurethane, then what do I do? I go on walks and observe what is around me and read up on the local farmland, military base, and prison complex. I wanted to use this body of work to get to know the town of Lompoc, where I moved after the stark realization that I could no longer sustain renting in Los Angeles.

The concept of stakeholders has stayed with me profoundly since my Venice Biennale projects, and I have been thinking that the biggest stake we all hold now is climate justice. When I was an urban dweller, the found objects I used were urban detritus. Now that I live closer to plants and animals, nonhuman stake-holders, such as snake molts and tree branches, become my readymades.

Lompoc Stories Series: Spacesuit 2021 was born out of a walk in the nature preserve. I saw this shiny thing sticking out of the ground. I thought it was a piece of plastic, maybe the packaging for an umbrella, but it was odd to see litter in this remote area. I was stunned upon recognizing that it was a snake molt. I am usually squeamish with such things, but the molt seemed to urge me to take it back to the studio. Six months later, I was researching the switch of Vandenberg Air Force Base to Vandenberg Space Force Base, where satellite launches and reconnaissance have become the specialty. From my living room windows, I can often see the vapor trails of rockets, and they look like snakes. I felt the snake left its skin behind to collaborate with me to make a piece about the sky above it. Those long fiber optic strands I kept in my studio for a number of years came to my aid. I think the unlikely coupling of snake molt and fiber optic cable in Lompoc Stories Series: Spacesuit 2021 was made possible by the limitation I set for myself.

WANG: Going through the exhibition, I felt a sense of ease and release. It’s as if the qualities that were always present in your work—humor, whimsy, idiosyncrasy—have recently flourished. They convey a sense of play and precariousness. These works feel unstable, at the edge of something. That is also revealed in the way these objects are sold. Could you speak to how the pricing of the work is related to sustaining your art practice?

TSE: I am allowing myself to enter into a new chapter where my work is not beholden to the existing system that I find unsustainable.

In conversation with the gallery, I gave myself permission for the work to not be archival. It’s okay if it disintegrates or breaks during the show, because fragility is the state of all things. It runs counter to the logic of a lot of galleries, which subscribe to art being a consumer-based object.

I also made all of the works in the exhibition the same price, shifting the focus from artwork as commodity to helping to sustain an artist’s practice. The price was tied to one month’s rent on my studio—and that alone.

Art prices are going through the roof these days, and much has been said about the fair remuneration of artists’ labor. Against the grain of both issues, I wanted to focus on something clear and irrefutable, the bare necessity of object making: having a space to work in for non-property-owners. It’s almost like a fundraiser: when you buy this work, you’re helping to sustain the artist by giving her the rent to pay for a studio so that she can keep making work. It’s more like a gesture of patronage, to sustain an artist’s practice rather than buying an object with a price tag that fluctuates with the art market.

The sense of being liberated that you picked up on is real. With this show, I’m saying: No, I don’t want to be operating under the principle of the colonial technocratic capitalist system. I’m going to make this work according to my terms, my daily life in this city, the things I see and their affordance, with the means I can afford. And I have nothing to prove. I’m asserting a lot of agency for myself and nonhuman stakeholders. That is the sense of liberation a viewer might feel in these pieces.

Shirley Tse is an artist based in California. Her sculptures, installations, photographs, and text works have been included in exhibitions in the United States and abroad since 1994.

Alice Wang makes sculptures, photographs, and experimental films. Her upcoming solo exhibitions will be presented at the UCCA Dune Art Museum in fall 2023 and the Vincent Price Art Museum in spring 2024. Wang is based in New York.