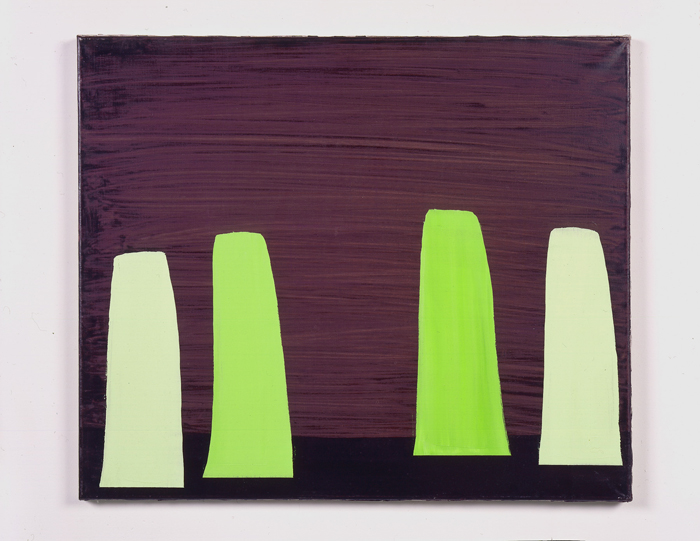

John Millei, Procession 96, 2005. Oil on linen, 20 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Ace Gallery.

Mitchell Kane: I’ve only known your work for a short time. You are from Los Angeles, with a gallery and educational affiliations, but you also position yourself as an outsider- insider, in the sense of being self-taught, and socially distant from the arts industry. This combination, along with the content of your work, I find mysterious. When I examine your paintings, a steady, but persistent, “abstrac- tion/representation” conundrum strikes me, but I can’t be more specific than that. Why don’t you tell me about your Procession Paintings—where they came from—and also the Maritime and Deluge Paintings, which were the preceding body of work, yes?

John Millei: The Procession Paintings were asking a simple question. I spent most of my career as a painter producing abstract paintings and an abstraction more or less based in a kind of landscape—and occasionally I would use flowers—but I never really addressed the figure. It was something I was avoiding, because with the invention of photography and cinema, I didn’t quite understand what the role of the figure in painting should necessarily be.

MK: And, you literally mean the figure and not figurative elements?

JM: Not the figure, the figure in painting, and potentially narrative or the implication of narrative. How it came about was that I was in Padua, Italy, and saw The Nuptial Procession of the Virgin panel in the Arena Chapel.1 I always loved Giotto and admired his work. So there I was, and his paintings seemed so formal, so contemporary, so reduced.

MK: Can you briefly describe the painting?

JM: It’s about six foot square in a huge wall of frescoes, because frescoes for Giotto in the Arena Chapel function as didactic learning tools for people of the period. They’re just cartoons essentially telling a story, scripture. So it’s easy to imagine the priests pointing, “There’s the procession of the virgin.” I saw them as storyboards. As I was looking at one panel I asked myself the question, how would I address painting the figure, if I had to do so? I then left Padua and went to Bologna and saw Morandi’s Museum.2 And, again the question came, how would I paint a still life? These questions couldn’t be more conventional within the history of painting, but it was something I felt that I needed to address if I wanted to call myself a painter— figure, still life, landscape, non-objective, etc.

MK: You might also phrase it by asking, what is the nature of genre?

JM: I guess it’s every genre, absolutely! So I decided to take the notion of painting as model, taking the reproduction of Giotto’s Procession and treating it as a still life, then taking it apart as Morandi did—a very small series of elements. Originally, it’s thirteen people in procession and they’re moving in the foreground, and the painting is pretty much divided right across the middle horizontally with sky above and figures below. It’s a very, very, strangely forced painting.

MK: Forced in terms of color?

JM: Forced in color, capacities—it’s a very flat painting.

MK: Blue sky, green ground.

JM: Blue sky, green ground, and various colors in the robes from turquoise and whites to reds and blacks. Five of the figures happen to be most forward grounded. What I did when I returned to Los Angeles was take a canvas about the size of one of the Morandi’s still life paintings, and I painted these shapes, which have become the procession shape. What they essentially are are robes with heads on them. I took the basic structure and reduced it the best I could… and I looked at them. I was actually quite fascinated by the fact that they looked like figures and that they really took on the characteristics of the human. Then, I very quickly realized that I could lean them or tilt them to do all sorts of things that would imply narrative, and relationships, and so forth. So there began the relationship of looking at the figure as a still life through looking at Giotto.

John Millei, Installation view, Ace Gallery, Beverly Hills, 2006.

MK: Why the large number of paintings? Isn’t there’s a point when a procession becomes a parade?

JM: Right. Numbers in my work are arbitrary, but necessary. I decided the moment I made the first painting that I was going to do two hundred of them; the number two hundred came up and I thought it seemed like a fair number. So I began. I currently have in my studio twenty-four sculptures for Brigitte Bardot3 and another group of paintings called twenty-four paintings for Los Angeles, which are paintings on velvet.

MK: Why twenty-four for Bardot and two hundred for —

JM: Well, that’s because there’s something incredibly arbitrary about it—at that moment I’m working in my notebook and I think I want to make something. I saw a documentary by Serge Gainsbourg4 on Brigitte Bardot, and I always had a thing for her as a young boy, and she recently turned into this weird animal rights activist and hard core conservative; a very peculiar woman. So I wanted to make sculptures and wrote down twenty-four sculptures for Brigitte Bardot, so it might literally be how it sounded to me.

MK: Twenty-four. If you made it a quantitative judgment would it be enough?

JM: That would be enough. It always comes that way to me. It comes as random as that.

MK: This approach creates an intuitive stance within your work. From the start, you say to yourself, “Well, you know Giotto, I think this project is two hundred paintings; I’d be able to complete two hundred.” Have you ever set a number and decided early on in the process that ten were enough?

Giotto di Bondone, Nuptial Procession of the Virgin, 1305-06.- Fresco, Arena Chapel at Padua, Italy.

JM: I once set a large number, but thought that ten was enough, but I continued. I always complete the original number, because I have found when I reach a point where I believe there is nothing more to be done I realize that I haven’t even begun to work with the that subject. I’m interested in moving beyond boredom, way beyond the quail trail feeling you get with producing something over and over again.

MK: What’s the impetus for continuing?

JM: I think it has to do with ideas about discipline. I’m a very intuitive person in many ways and I make choices, but I do like it when there’s something structured about thinking. So for me to say that there are two hundred Procession Paintings, I might say that at fifty I was fairly convinced I had run the course of this practice. Then I’d take a few months, not work on them and work on other things at the studio.

MK: It appears to me that you’re asking something else of these paintings. Are you?

JM: What I really wanted with the Procession Paintings is to build all kinds of limitations into my practice. I wanted to take away much of the dexterity and facility that I have used in other paintings.

MK: Do you mean in terms of their physicality?

JM: Yes, the physical nature of painting. In some way if I were to be critical of my studio practice, sometimes I rely too much on the physical nature of paint — thick, thin, gloss, stain — putting work on the floor and pouring, picking it back up to work some more. In some cases, one can say they’re sort of like guitar solos. They’re at times maybe too facile. In the Procession Paintings I wanted to reduce everything down, giving myself one scale [20” x 24”], using a few simple converted tools, a few paintbrushes, and a limit to the amount of time I would work on each painting. I wanted a place where I was reducing the possibilities I was going to give myself to complete the project. I wanted a contained space, so I created a Ninetieth Century studio with an easel in my home. I never owned an easel before and started to work in a very different way.

MK: For you this is a different place for you to paint; it’s not some place you usually go to work on paintings?

JM: No. When I was working on the Procession Paintings, it was more like puttering. I was home, in a domestic setting, so I would get up, make coffee, go make a figure, which would take about a minute, check emails, take the dog for a walk, paint another figure. So puttering in my daily life lost the performative nature of being an artist—going to the studio to stand before your project. These paintings seem to escape that somehow. I can watch Letterman and right before bed put a figure down. It really became integrated into my life. They were made very much like that.

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1951. Oil on canvas, 15 3/8 x 17 3/4 inches, Museo Morandi, Bologna, Italy.

MK: In looking at your exhibit at ACE, I noticed your figures are extremely Gumby-like in their form and in their applied pliability. In watching further, I had a sense that the figures were wading knee deep in water, but somehow walking in a linear direction, which may be due to the over-painting in some of the pictures and lack of lower body detail. You have used the theme of water before, in past works such as the Maritime and Deluge Paintings.

JM: In some of them you’re completely accurate. I put a transparent band to have them walking in water, which mostly comes from my observing people at the beach. I’m fascinated by people walking in water, and some do suggest that, but I never really thought about water when I painted them. The Gumby-like aspect goes back to Giotto’s paintings. To me, when you see them in the Arena Chapel — if we don’t mythologize these paintings in the way history has described them—they function as cartoons. They are learning tools for people that were essentially illiterate. So I returned them to cartoons. I reduced them to their cartoon-like quality.

MK: I have to ask, are your paintings educational?

JM: They are for me. I think anyone can look at the Procession project as a painting lesson. I think it walks one through how formal painting really is. No matter what you’re painting it comes down to a two-dimensional plane that requires dexterity and an understanding of the formal. The formal is infinite! By the sheer number, I hope it contests the idea that this work is highly sensitive and romantic, although there is a certain layer of that, they’re beautiful paintings—I know that—and delicately painted.

MK: How do you know that? What makes you say that?

JM: What makes me say that they’re beautiful?

MK: Yes. How do you know that?

JM: I feel I have a fairly clear grasp of how I describe beauty and also how our culture, and what I mean by our culture is the art world, locates beauty. They’re beautiful in the way that, say, Matisse is beautiful.

MK: Yes, Matisse I understand. What I’m asking you specifically is, how do you KNOW your paintings are beautiful?

JM: I set out to traffic in beauty. I was thinking about the operation of painting and beauty and it seemed like a very dangerous place to go. If I were going to paint the figure and the still life, why not add a layer of beauty and allow them to be delicate and eloquent and beautiful in the most bourgeois sense?

John Millei is a painter living and working in Los Angeles and is represented by ACE Gallery in Los Angeles. Millei has educational affiliations with Claremont Graduate School and Art Center College of Design.

Mitchell Kane is an artist, curator, writer, and graphic designer living and working in Los Angeles. Kane is the Fine Art Department Director at Art Center College of Design and most recently completed a Conversation Project at the former Convento del Carmen in Guadalajara entitled Jalisco Demonstration Project: Ejercicios de Equilibrio Precario.