Nilo Goldfarb on the architectural legacy of the late Eli Broad.

Eli Broad at the opening of the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum. Zaha Hadid Architects, The Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, 2012. East Lansing, Michigan. Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects. Photo: Iwan Baan.

Eli Broad (June 6, 1933–April 30, 2021) once told a journalist that his secret weapon was a sharpened pencil with which to work the last penny out of a deal.1 More prosaically, he also cited the neo-Keynesian principles of economic equilibrium he acquired from Paul Samuelson’s economics textbook, which he studied at Michigan State University under Walter Adams in the 1950s.2 Broad’s first company, Kaufman and Broad (now KB Home), built and financed customizable tract homes. The firm ushered in an era of corporate homebuilding that hugged the curves of fluctuating markets. They lowered barriers to getting mortgages—and, you might also say, to achieving the American Dream. Eli Broad (rhymes with load) would have been Eli Brod, but his Lithuanian father changed the spelling, thinking this would help Americans pronounce it. Americans would know his name, but they would continue to mispronounce it.

When Broad entered philanthropy in art, science, and education, he took a similarly entrepreneurial approach: He made sure the money he donated, including almost $1 billion to the arts in Los Angeles over the course of his lifetime, was invested in rationally led institutions that were well positioned to generate demonstrable social returns.3 Broad’s philanthropy also featured another foray into building: commissioning “star architects” to design buildings for high culture, medicine, and education, all bearing the Broad name. Prompted by Broad’s death in April 2021, this essay approaches Broad’s contribution to architecture and building as a case study in the concrete effects of venture-philanthropy.

Eli Broad in 2013 at the construction site of The Broad. Courtesy of The Broad and Capture Imaging. Photo: Ryan Miller.

The Award Winner

The story of the billionaire begins with $25,000. In 1957, 24-year-old Broad was working as an accountant. He had just completed a degree at Michigan State University in under three years and married 18-year-old Edythe Lawson while still in school. Edythe was pregnant with their first child.4 Broad was watching his accounting clients profit from a boom in tract homes inspired by Levittown, American real-estate developer William Levitt’s cookie-cutter communities in New York that were not only famous for their economy but also infamous for their exclusion of minority residents.5 Broad wanted to seize this opportunity himself but lacked starter capital. His Jewish Lithuanian immigrant parents, dressmaker Rebecca Broad (née Jacobson) and housepainter, union-organizer, and convenience store owner Leo Broad, didn’t have the funds. However, in 1957, Edythe’s father, a chemist, lent $25,000 to Broad and Edythe’s cousin’s husband, contractor Donald Kaufman, and the duo went into business.6

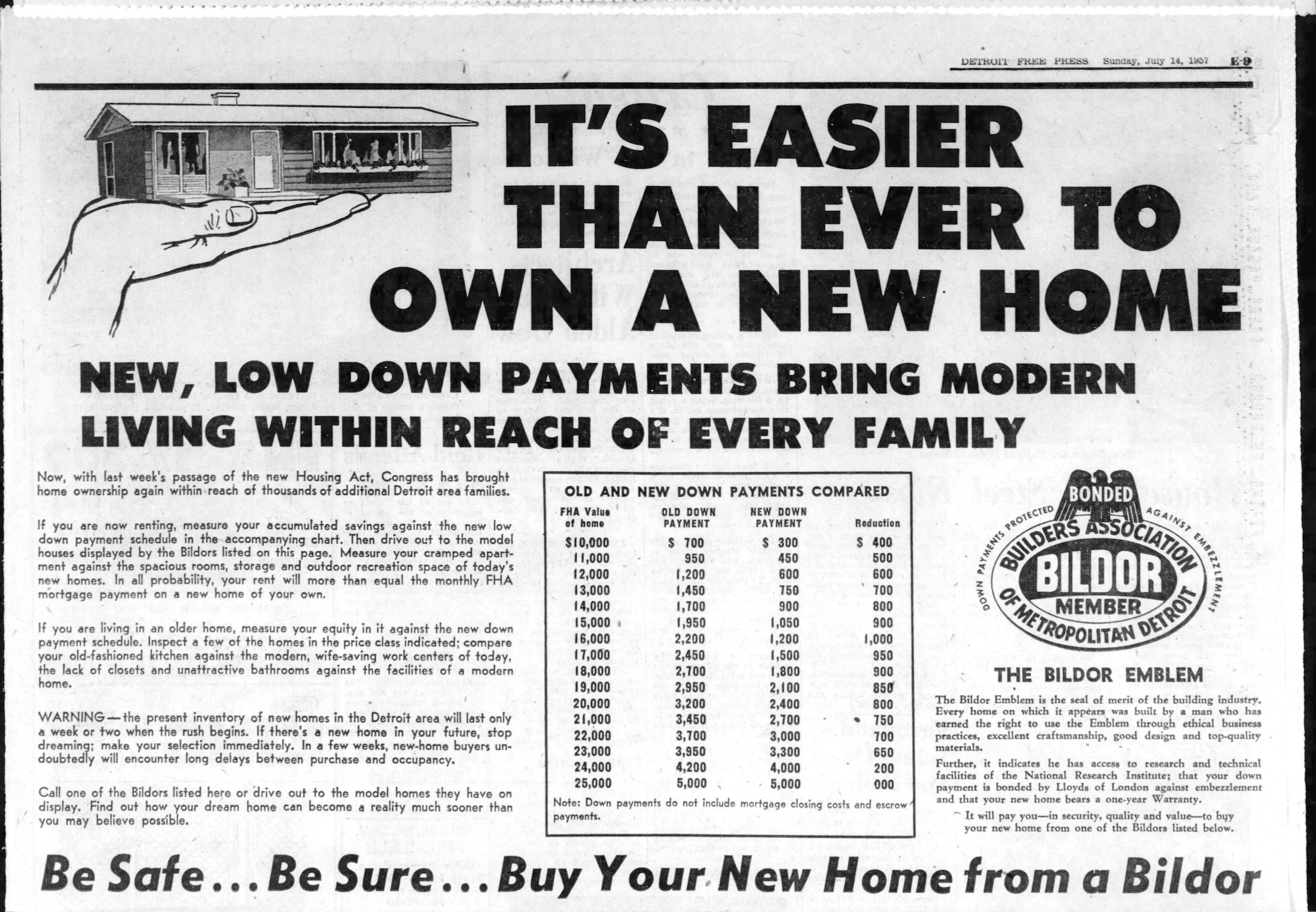

Kaufman and Broad’s debut home, which they called the “Award Winner,” was a calculated reworking of Levitt’s model unit. The Award Winner had no basement and could therefore be built on a concrete slab, eliminating the cost of digging a foundation. This strategy, already common in Ohio but novel to Detroit, enabled them to lower monthly mortgage payments to near the going rate of renting. Kaufman and Broad joined the hundreds of registered Bildors (a nickname for members of the Builders Association of Metropolitan Detroit), whose listings for model homes populated the classifieds of newspapers such as the Detroit Free Press.7 Early newspaper advertisements for the Award Winner promised veterans little or no down payment on the homes, taking advantage of the GI loans that had been provided by the Federal Housing Association since 1944 as a financing incentive.8 The nascent company sold 136 homes in its first year. Over the following two years, the business expanded rapidly, acquiring government contracts for dorms, barracks, and public housing. By 1961, Kaufman and Broad became only the second homebuilding company to be publicly traded (and, eight years later, the first listed on the New York Stock Exchange), raising $1.8 million with their initial offering.9 By 1964, the company had expanded operations to the cities and exurbs of Chicago, New York, Phoenix, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Kaufman and Broad continued to do business in Detroit, forming the subsidiary Award Winning Homes, the corporate homebuilder’s homespun trophy operation.10

Advertisement in the Detroit Free Press, July 14, 1957. Detail.

Salem Square

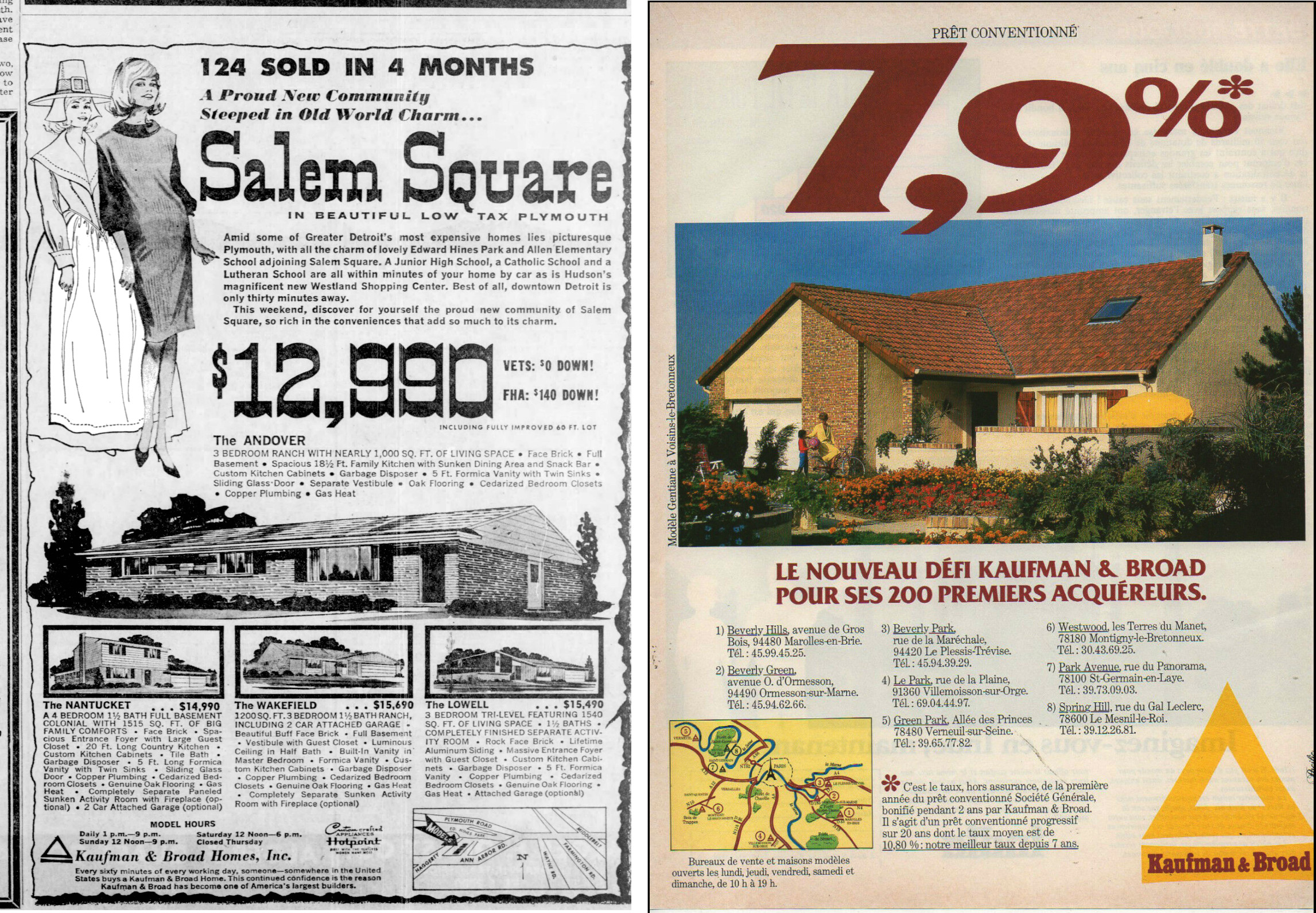

If Levittown’s genius consisted in mass-producing containers for postwar American life, KB’s resided in their ability to modularize the containers’ parts, customizing the American dream of home ownership to fit individual tastes and budgets. Broad’s innovation was not merely thrifty home construction but also fluency in the signs and symbols that reside in the American unconscious. This started with the Award Winner, from which the basement was not subtracted so much as dislodged; an aboveground carport took its place. Deluxe add-ons inched buyers to their fiscal limits; austere variations lured erstwhile renters into mortgages. The basic units, ranch (a single-story house with a carport), colonial (a multistory house with brick siding), and generic multilevel (a “tri-level”), served as the syntax for an expanding lexicon of lifestyle fantasies—the economic base for a superstructural form. A wide range of thematic communities sprung up as Kaufman and Broad continued to expand. One monarchically styled development in Detroit, King’s Row, included models such as the Regency (a 1,000 square foot ranch) and the Imperial (a 1,400 square foot colonial). The colonial New England-themed Salem Square featured models such as the Nantucket and the Andover. Arizona’s Polynesian Paradise applied an exoticized dream of island life to budget-rate adult living.11 Chicago’s anglicized Brandywine residences deployed Tudor-style architecture to promote the novel conveniences of “maintenance-free living” in a planned community.12 Amid the upheavals of 1968, Kaufman and Broad shipped California dreaming overseas with the creation of the Beverly Hills and the Westwood on the outskirts of Paris. These Los Angeles namesakes reproduced communities the firm had already built in the suburbs of Chicago.13 By the middle of the 1970s, market cycles had waned. Kaufman and Broad leaned on mobile home production and introduced a line of finish-it-yourself models.14 These homes were advertised with the family names (“the DeuPrees’ custom home”)—and the largely white, sometimes immigrant faces—of model homeowners.15

Kaufman and Broad advertisements. Left to right: Detroit Free Press, April 25, 1964; unknown, c.1968.

The Research Home

Kaufman and Broad’s advertising trafficked in fantastical displacements but also spoke a language of economic realism, a language that was crucial to their business model, given the corporation’s increasing capacity to bankroll their own sales. In 1965, the company formed a subsidiary, the International Mortgage Company, to finance houses directly. In 1967, Broad, who by that point had been appearing regularly in the Detroit and Chicago papers to bemoan the repercussions of federal lending restrictions for home prices, went on the record to predict a historic housing boom.16 The article, which ran in major newspapers from California to New York, encouraged homebuyers to get in on the action. In 1972, the Boston Globe ran an article (printed above the stock listings) in which Kaufman and Broad’s economic success was praised as proof that homebuilding should be corporatized.

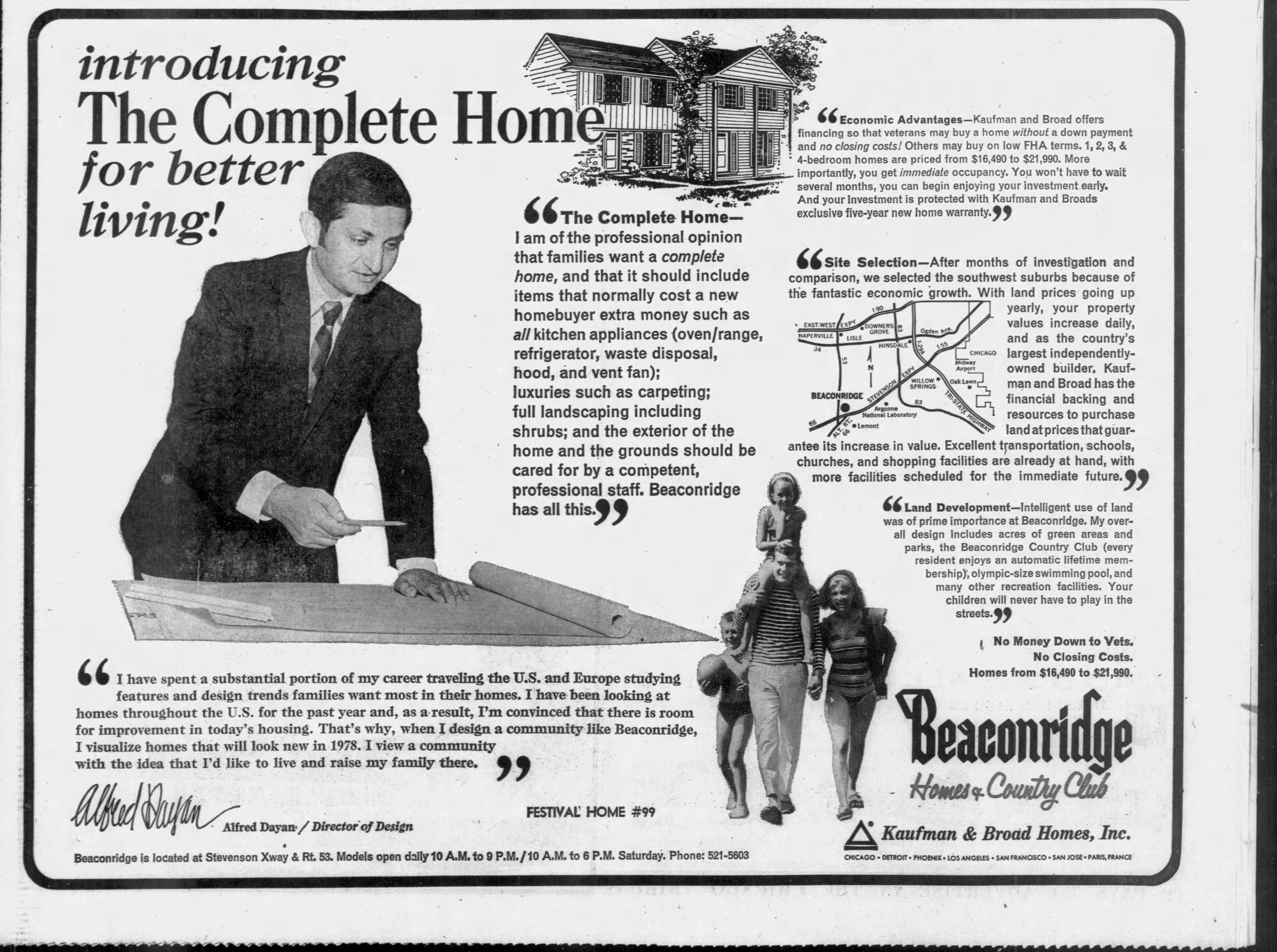

Meanwhile, Kaufman and Broad translated their image as a calculated business machine back into a vision of lifestyle for buyers. One ad depicted Alfred Dayan, the company’s Director of Design, hunched over a drafting board, with copy narrating his role in such macroscopic considerations as site selection and land development.17 Kaufman and Broad reimagined the home itself optimized through rational enterprise with their Research Series homes, which bore codified names such as R-34 and S-2 and were said to feature “the perfect blend of features, convenience, and economy.”18

KB held the field as the nation’s premier corporate homebuilder, though a crash affecting the entire housing market drove Broad to diversify the company. In 1971, Kaufman and Broad acquired Sun Life Insurance. Reflecting on the decision in 1978, Broad told Business Week, “Life insurance is the perfect complement to our housing operations. . . . When interest rates are high, the life insurance operations can [invest premiums collected] in higher yields for long periods.”19 The company underwent multiple strategic reconfigurations over the years. They subsumed various life insurance companies throughout the 1970s and 1980s, cherry picking lucrative components of failing operations and shifting their own focus toward retirement insurance. In 1973, two years after the company acquired Sun Life, Broad stepped down as CEO of Kaufman and Broad. He continued to hold a controlling share in the company, however, and returned twice to the role of CEO—once in 1975 and again in 1988.

Kaufman and Broad advertisement in the Chicago Tribune, September 7, 1968.

Arata Isozaki’s MOCA

While the operations of Kaufman and Broad moved into greater financial abstraction, Eli Broad began exerting concrete influence on public policy. He spearheaded the winning Senate campaign for the Democrat Alan Cranston in 1968 and co-chaired the Democrats for Nixon campaign in 1971. He also became a patron of the arts. Broad was the first chair of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles. Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, he fundraised and campaigned for the fledgling institution. He worked with artists Robert Irwin and Sam Francis to recruit former Centre Pompidou director Pontus Hultén and to acquire 80 pivotal works from Giuseppe Panza’s coveted collection of Abstract Expressionism and Pop.20 (Hultén later returned to Europe, where he felt that a greater degree of state funding in the arts enabled him more freedom as a museum director.21) Broad had high hopes that his investment in MOCA would transform Los Angeles into an art capital. He was also a capitalist realist: he knew it would take the skillset of a CEO to pull off a contemporary art museum in Los Angeles, a city dominated by the Hollywood culture industry and without the consistent legacy of arts funding found in cities such as New York. As chair of the board, Broad negotiated a prime location for Arata Isozaki’s critically celebrated 1986 MOCA building on Grand Avenue in downtown Los Angeles. He bargained with adjacent developers, the California Plaza Partnership, fighting their pressure to locate MOCA inside the lobby of an office building. But he agreed, in a final compromise, to avoid blocking the view from nearby towers: Isozaki would build his museum below grade.23

Arata Isozaki, MOCA Building, 1983. Silkscreen on paper, 28¾ x 20¼ in. Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Donated by Joseph Giovannini. Photo: Jeff McLane.

The Broad Art Foundation

The Broads also began collecting art. Eli followed the lead of Edythe, who inaugurated the couple’s collection with the purchase of prints by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Georges Braque and an early drawing by Betye Saar.24 “When Eli got involved,” Edythe recalls, “the budget went up.”25 While he admitted that he didn’t have a great eye, Broad brought to art collecting a strategic attitude and a dedicated team of experts.26 In 1984, the Broads founded the Broad Art Foundation with the stated aim of facilitating the circulation of works from their private collection to museums, universities, and other public venues.27 In 1989, Frederick Fisher and Partners built out a space for the Broad Art Foundation in a former telephone switching station in Santa Monica. Open by appointment to “Collectors, museum professionals and qualified art scholars,” the foundation invited select guests to “view, study, and consider [the works] for exhibition.”28 The showroom displayed part of the couple’s holdings—then some 200 works by Ross Bleckner, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Cindy Sherman, and a host of other prominent 1980s artists. Meanwhile, the rest of the collection circulated on loan.29 The rotating display employed a similar strategy to that of the model homes back in Detroit: it provided a virtual context in which a target audience could imagine future opportunities, sowing the seeds for proliferation. Fisher’s renovation gently reworked the industrial structure into an understated backdrop for art, leaving many of the industrial building’s concrete walls exposed. The architect garnered wider recognition for this technique eight years later, when he applied it to his re-composition of a Beaux Arts school building for MoMA PS1. The Broad Foundation followed the example of MOCA’s Temporary Contemporary (now The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA), the Downtown Los Angeles warehouse in Little Tokyo that Frank Gehry renovated to house MOCA’s collection while MOCA Grand was under construction. It embraced industrial architecture just as it was becoming fashionable.29

Three Academic Buildings at Pitzer College

In 1991, Broad put $3 million toward the construction of three new buildings on the campus of Pitzer College. Broad was on the college’s board from 1970 to 1982, serving as chair for six of those years, and he described his gift to the social justice-oriented college as a deliberate investment in the production of changemaking individuals. “Pitzer’s mission in education is more important today than it’s ever been,” he said on the occasion of the buildings’ completion. “We produce all the lawyers and consultants we need. We need people to help our society work better as a multiracial society. Pitzer graduates go out into the world and do meaningful things for our society.”30 From Broad’s shortlist of ten architects, Pitzer’s facilities committee chose Charles Gwathmey, a constituent of the New York Five, or the “Whites,” so-called for their inclusion in the book Five Architects (1972) and for their repeat improvisations on Le Corbusier’s well-known white-walled modernism. Gwathmey drafted the three seafoam-accented Pitzer buildings in a playful idiom of truncated primary forms and subtle curving surfaces. This approach was less “White” and more “Gray,” the color assigned to the five Postmodern architects chosen to give a counterargument in the Five on Five forum organized by Robert A. M. Stern in 1973. Broad Hall contains teaching and research space for the psychology, sociology, and anthropology departments, and the Gold Student Activity Center provided new recreational facilities. The mixed-use Edythe and Eli Broad Center serves as the college’s official entrance, housing the university president’s office amid admissions and faculty offices, classrooms, and a performance space. The combination of various strata of power and disciplinary specialization under the same roof was billed polemically as an embodiment of the college’s egalitarian ethos of horizontal dialogue.31

The Broad buildings were met with ambivalence. One commentator, writing for Pitzer’s campus journal, The Other Side, decried them as a sign that the campus, which prided itself on its rebellious, student-led culture, was being institutionalized.32Auteur architecture, the visible expression of Broad’s investment in educational facilities, had become the emblem of the corporate giving that underwrites educational freedom. Indeed, as Broad made decisive investments in educational centers for critical thinkers and artists, the architecture bearing his name made his underwriting of creative freedom explicit, posing to its inhabitants the question of whether corporate investment could produce them in the same way it produces leaders in business and law.

The Edythe and Eli Broad Studios at CalArts

The Edythe and Eli Broad Studios at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), commissioned in 1992 from Gehry protégé Jeffrey Daniels (famous for his deconstruction-of-a-bucket KFC on Los Angeles’s Western Avenue33) and Elyse Grinstein, brought into tension the top-down intervention represented by architecture and the supposed freedom embodied by artists.34 The seven semi-detached modular units, each capped with brightly colored sheet metal clerestory windows, were scattered in a village-like formation to reflect “the loose, sometimes even anarchical approach that is central to this very progressive school of art.”35 The new units were an allegory for a revolution, but institutional officialization coincided with added restrictions on their use. According to the Los Angeles Times, the units have been dubbed “studio-condos” (despite their lack of bathrooms). The form is a subtle permission to transgress, given that CalArts students, known for living in their on-campus studios, are forbidden from doing so.36

Jeffrey Daniels Architects, The Edythe and Eli Broad Studios at the California Institute of the Arts (1992). Concept illustration. Valencia, California. Courtesy of Jeffrey Daniels Architects.

Jeffrey Daniels Architects, The Edythe and Eli Broad Studios at the California Institute of the Arts (1992). Valencia, California. Courtesy of Jeffrey Daniels Architects. Photo: Douglas Hill.

The UCLA Broad Art Center

In 2006, the Broads paid $23.2 million to see Richard Meier, another member of the New York Five and architect of the Getty Center in Los Angeles, transform the University of California Los Angeles’s William Pereira-designed Dickson Art Center into the Broad Art Center. The adaptive reuse effort at the public university was praised by Los Angeles Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff as a masterful deployment of Meier’s Corbusier-inspired arsenal to address the needs of art students.37 The Pereira structure, damaged in the 1994 Northridge earthquake, was a concrete office block and a six-story tower. Meier’s firm gutted the tower to create loft-style studios, running shaded walkways along the exterior of the building. They added a ramp at ground level sloping up to the back entrance, through the second-floor café, and out onto the grass courtyard. At the furthest edge of the popular student hangout, Richard Serra’s T.E.U.C.L.A. (2006), a 42.5-ton steel “torqued ellipse,” provides a semi-concealed public space, the interior surface of which is regularly marked by graffiti. The architecturally scaled sculpture, included in the Broads’ gift to the campus, cedes power to its viewers/inhabitants by providing a partial respite from surveillance, not unlike Serra’s legendary Tilted Arc (1981) prior to its removal from Manhattan’s Foley Federal Plaza. In this case, the sculpture is embraced by the institution as a powerful symbol of artistic freedom. This dynamic is an ongoing lesson in the exchange of agency between patron, artist, and public; T.E.U.C.L.A. has been embraced by art students influenced by institutional critique and savvy to its provenance, who imagine new possibilities for its use in performances and installations.

Richard Meier Architects, UCLA Broad Art Center, 2006. Los Angeles, California. Creative Commons License.

High School #9

Broad’s educational building efforts became most overtly political with the construction of the Coop Himmelb(l)au-designed Central Los Angeles High School #9 (now the Ramón C. Cortines School of Visual and Performing Arts). In 2002, Broad caught wind of a plan by the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) to build a school on the site of its former headquarters on the corner of Grand and Caesar Chavez. Broad successfully lobbied for the new facility to house an arts-oriented high school. Though the district had already hired the architecture firm AC Martin to produce plans for the new school, he persuaded them to hold a competition to select a new architect. Coop Himmelb(l)au won the competition and took over the project. To save costs, Wolf Prix, Himmelb(l)au’s resident architect, partially adapted AC Martin’s completed plan. Yet, to the strapped school district’s political embarrassment, the budget escalated wildly; Prix’s structure ran up costs of $232 million.38 Broad contributed $5 million.39

Also in 2002, Broad formed the Broad Superintendent Academy, which trains school administrators with a business management philosophy of “continuous improvement” and an anti-union ethos.40 By 2011, 21 of 75 major school districts in the United States were led by Broad-trained superintendents, including LAUSD’s John E. Deasy.41 In his lifetime, Broad and the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation directed upwards of $600 million to charter schools—government-funded public schools managed autonomously from the state school system.42 Lobbying by Broad and other members of his economic class in favor of charter schools has been criticized by unions and public school advocates as an attack on the public school system: by funneling their funds toward individual charter schools, wealthy philanthropists have overlooked systemic improvements in favor of press-grabbing improvements to special schools.43 Broad fought unsuccessfully to make Cortines School a charter school; the school is part of the regular public school system, and they admit no fewer than 70% of their students from low-income neighborhoods.44 As a budget-starved public school, Cortines School has struggled to offer a curriculum that lives up to its state-of-the-art facilities. Within the first four years of the school’s existence, Broad made another unsuccessful effort to remove the school from its district and institute an admissions policy that would value “merit” over equity.45

The Cortines School’s buildings remain an ambivalent statement. The plan’s irregular pyramids, set against Martin-derived concrete containers, create a charged pastiche. It is at once a poetic statement on Los Angeles’s concrete sprawl and an allusion to Soviet monuments in Tatlin’s wake or after the fall of the Berlin wall: the fenced-in campus draws comparisons to an East German housing block. When probed, students offered that their idiosyncratic campus mirrored their quirky, gangly selves, striving for recognition.46 Perhaps Broad wanted this school to reflect his own rise to the top.

Coop Himmelb(l)au, High School No. 9, 2008. Los Angeles, California. © Roland Halbe, used with permission. Photo: Roland Halbe.

Broad Residence #1

The same year as the Broad buildings went up at Pitzer, the Broads commissioned Frank Gehry to create a home for them in Brentwood. After two years, when Broad felt that Gehry had taken an unreasonable amount of time to complete the drawings, Broad broke the initial agreement, which had given Gehry great flexibility regarding both time and budget. After paying Gehry his design fee, Broad hired the corporate developing firm Langdon Wilson to build the house.47 The move infuriated Gehry, who has consistently trusted his in-house developers to ensure his firm’s creative control over the final product. Gehry disowned the work, excluding it from his portfolio. He also declined all invitations to visit the Broads in Brentwood. Poring over photographs of the Broads’ home published in Architectural Digest, the impression is of a more-or-less Gehry-shaped structure lacking in the subtlety of finish found in buildings from Gehry’s oeuvre.48

The Walt Disney Concert Hall

This scenario was repeated when Broad joined the planning committee for the Walt Disney Concert Hall, which Gehry had been chosen to design. Again, Broad pushed for an outside developer to realize the architect’s plans. This time, however, he was overpowered by Gehry’s supporters: Diane Disney gave $15 million on the condition that Gehry’s firm remain on board until the hall’s completion. While many have claimed that Broad’s fundraising efforts saved Disney Hall, it is equally the case that others on the board saved the project from Broad’s attempts to finish it.49

The Disney Hall viewed from The Grand LA construction site across Grand Avenue, March 2020. Frank Gehry Partners, The Walt Disney Concert Hall (1996). Los Angeles, California. ® Related Companies, 2020.

The Broad Contemporary Art Museum

Both master builders, Broad and Gehry differed radically in their manners of appropriation. Whereas Gehry elaborated the creative possibilities of developer collaboration, including construction-site improvisation and calling attention to low-cost construction materials, Broad leveraged his donations to pressure organizations to economize their building plans in accord with his own shrewd evaluation. On the construction of the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Broad subbed as a penny-pinching developer, using his sharpened pencil to put a fine point on the deal—and to poke the architect. In a negotiation with Broad that the architect Renzo Piano likened to torture, the original design was significantly economized.50 The skylights were cheapened and all indoor stairs were removed in favor of external escalators and a central freight-sized elevator—a decision that permitted the building to boast of “one of the largest column-free art spaces” in the world.51 Broad brought to high architecture the same accountant’s trick he used to launch Kaufman and Broad: he subtracted costly features while simultaneously maximizing status-conveying features.

Renzo Piano, The Broad Contemporary Art Museum at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2008. Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: Laura Cherry.

The Caltrans District 7 Headquarters

Critical differences aside, few architectural practices provide a clearer precedent for Broad’s market-practical positivity than Gehry’s. Gehry has consistently attributed his success to his capacity to work with the building industry, arguing that architects must negotiate with urban developers to ensure that their art is actually built.52 Broad may have overlooked some of the art in architecture, but he shared Gehry’s view. In a project for the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro), Broad facilitated a design competition that stipulated in advance the price point and the role of the contractor in construction. The winner of the competition, Morphosis (Thom Mayne), worked with Clark Construction and various other advisors. Remembering the project as a personal achievement, Broad recalled the spirit of collaboration. “Thom, the architect, would say, ‘We need this. You can’t give up on that.’ And the developer would say, ‘That’s too expensive. What else can we do?’”53

Morphosis (Thom Mayne), The Caltrans District 7 Headquarters, 2004. Los Angeles, California. Creative Commons License BY-NC 2.0. Photo: CTG/SF.

The Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum

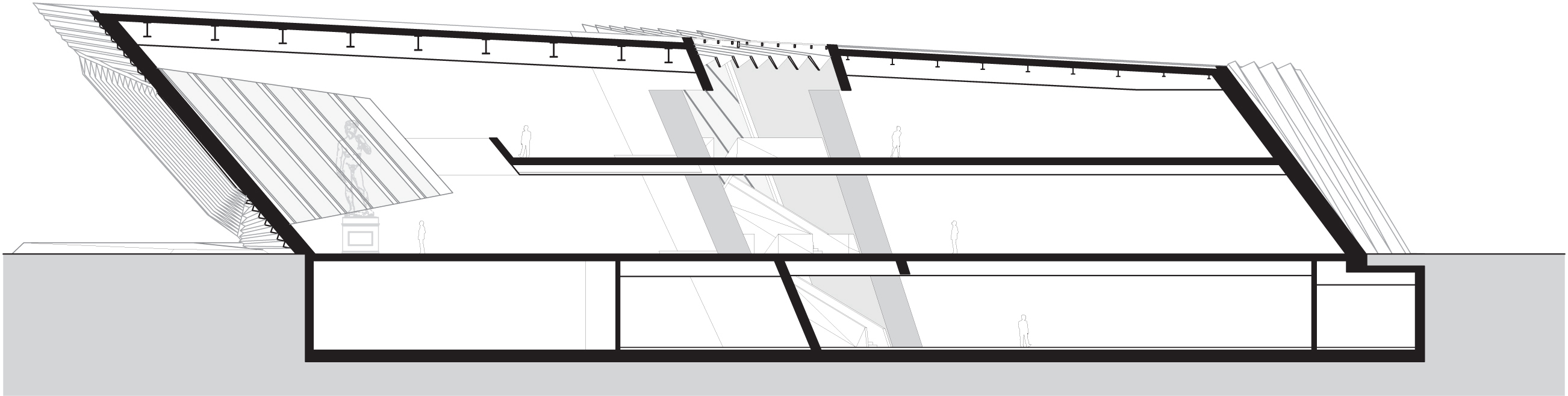

Broad also shared Gehry’s philosophy that every project is a social and economic investment—that commerce and culture go hand in hand in bringing new life to a region. When, in 2007, Eli Broad gave $28 million to his alma mater, Michigan State University (MSU), to construct the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum on their campus, Broad instilled in his collaborators hopes for the Bilbao Effect, so called after the economic glow brought to a postindustrial Basque city by Gehry’s Guggenheim building. Prior to making his donation, Broad turned down offers to transform the old museum. MSU president Lou Anna Simon remembers Broad complaining that “the site there was too constrained.” Simon found an ideal location for the museum on Grand River Avenue, but only after being convinced by Broad that “art museums could be very important game-changers for communities.” Broad continued to raise the stakes. According to Simon, “Eli was adamant that there needed to be an architectural competition.”54 The museum chose architect and critic Joseph Giovannini to lead the search. Party to the selection process were Michael Govan, LACMA’s CEO, and Edwin Chan, then-partner at Gehry’s firm and former project manager of the Guggenheim Bilbao. Among the five finalists, two others, Coop Himmelb(l)au and Morphosis, were architects with whom Broad had worked or would work in the future. The committee chose a proposal by Zaha Hadid. (The choice of Hadid, an Iraqi woman, during the US War in Iraq underscores the Broads’ socially progressive values.) Prior to the museum’s opening, the university commissioned an economic report from the Lansing-based Anderson Economic Group, which predicted millions of dollars in returns for the region.55 Various articles described the project as a rustbelt Bilbao. Broad bolstered this sentiment, telling interviewers, “Without any question, [the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum] will be a big boost to tourism for East Lansing and central Michigan.”56 Following the groundbreaking ceremony, Giovannini, whose connection to Broad dates to an article he penned for the New York Times upon the construction of MOCA’s Grand Avenue building, went to the press with a laudatory review of Hadid’s new structure.57 He did this again for Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Broad museum on Grand Avenue, in Los Angeles.58 The economic upshot of the Broad Museum at MSU has yet to be seen. When, in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, Mónica Ramírez-Montagut was hired as the Michigan museum’s new director, she related her own Bilbao dream deferred, citing the years-long process surrounding development that preceded Bilbao’s economic windfall as reason to hold out hope for East Lansing.59

Zaha Hadid Architects, The Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, 2012. East Lansing, Michigan. Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects. Photo: Hufton+Crow Photographers.

Zaha Hadid Architects, The Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, 2012. East Lansing, Michigan. Schematic of south elevation. Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

Lago Vista

Even after Broad sold his shares in the company, KB Home built on the precedent set by their founder’s pioneering expansion of the housing market. The company began, in 2000, to offer HUD-insured, no-money-down mortgages through Fannie Mae in new communities pitched, once again, primarily at low-income and immigrant groups. One such community, Lago Vista in San Antonio, Texas, centered its imaginary on a “lake” that is in fact a former runoff pit from an asphalt producer. As the housing bubble approached bursting, HUD’s mortgage review board accused KB Home Mortgage (KB Home’s financing division) of violating HUD-insured loan agreements by extending leases to ineligible borrowers and falsifying information, as well as overcharging. KB Home settled out of court with a payment of $3.2 million—the largest fine the review board ever received.60 With Broad’s death, we are left with the productive organizations that Broad not only set in motion but imbued with a culture of guaranteed growth.

Grand Avenue

The Grand Avenue Project initiated with Broad’s support continues to develop the Downtown Los Angeles strip atop Bunker Hill—currently lined with no fewer than five Broad-supported architectural works—with the goal of making it Los Angeles’s cultural center.61 The project was approved by Los Angeles City Council and the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors in 2007, at the start of the great recession. Despite a rocky start, the initiative has succeeded in increasing greenspace through the renovation of Grand Park and in allocating an adjacent lot for the construction of the Broad museum. The final phase of the project is nearing completion, with the construction of Gehry’s massive $1 billion “live, shop, work” space, The Grand, which continued through the Covid-19 pandemic. Gehry has billed the project as a bridge between the cultural activities taking place inside Disney Hall and the street, creating a lively community.62 The renderings depict a crowd the size of a small festival gathering in the street between the new complex and the Disney Concert Hall, as well as visitors or residents ambling on the towers’ terraces. For all the glitchy allure of Gehry’s staggered towers, the “community” planned by the architect appears mall-like, based almost exclusively on consumption at luxury shops, restaurants, and attractions. Like a storefront Bilbao, the massive urban complex earns its architectural freedom by promising to rake in massive profits.

Frank Gehry Partners, The Grand LA, under construction. Rendering, 2021. Courtesy The Grand LA.

The Broad

Broad made his final architectural statement in 2015, with the Broad. Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), the private museum sits right next to Gehry’s Disney Hall on Grand Avenue. The museum has a distinctive populist appeal: the Broad sees on average more than 900,000 visitors per year, and they come from a significantly younger and more diverse demographic than visitors to most other museums in the country.63 The museum is a spectacular masterpiece of contemporary user-experience (UX) design. “Change the angle of vision,” writes Giovannini, “and the illusion shifts, encouraging visitors to keep moving, as though this were a new kind of rainbow to chase.”64 Works from the Broads’ collection are exhibited in a 35,000-square-foot, column-free exhibition space gridded with temporary walls and daylit from three directions. The display of the permanent collection, despite its clearly art historical and thematic grouping, is monotonously large in scale, like a continuous series of billboards, and well-suited for legibility in the background of selfies.65

Eli Broad at the civic dedication of The Broad, September 18, 2015. Left to right: County Supervisor Hilda L. Solis, Elizabeth Diller, Mayor Eric Garcetti, Eli Broad, Governor Edmund G. Brown, Edythe Broad, and Joanne Heyler. Diller Scofidio + Renfro, The Broad, 2015. Courtesy of The Broad and Capture Imaging. Photo: Ryan Miller.

In commissioning his legacy building, Broad reprised Kaufman and Broad’s seventies campaign of fiscal realism, but with a surrealistic twist. DS+R masterminded the museum’s central metaphor of the Veil and the Vault, a metaphysical analog for the public exposition of a private collection. The Veil refers to the building’s elaborately engineered fiber-reinforced concrete envelope, which was inspired by the exterior lattice of Daniel, Mann, Johnson, and Mendenhall’s American Cement Building (1964), meant to demonstrate the potential levity of the company’s product. The Vault refers to the storage unit that houses the collection. On the exterior, the Veil is lifted at the entrance to reveal an opening in the sheet-glass box below. The sinuous interior is made up of opaque, modeled walls. Visitors’ passage through the museum is theatrically contrived.66 The most direct route between the public-facing floors of the museum is a hydraulic elevator with a glass ceiling. Light pours down the chute from the museum’s porous roof, but it is a ride without a view: the elevator glides through the Vault in a concrete channel. Most visitors ascend to the Broad’s main floor on a 105-foot-long escalator through an organic concrete tube that opens into the first of several enormous, sunlit galleries. Visitors who take the stairs on their way out are cued to pause at a platform where a round, cavity-like window offers a composed view into the estate’s art bunker, the Vault. Broad, whose first venture as a young capitalist was a house with no basement, was ultimately aware of the role that storage plays in the American Dream. This interior chamber, like a basement above ground, is the museum’s exposed subconscious. Broad’s dream of private ownership cuts across class; his opportunity is ours too.

Nilo Goldfarb is based in Los Angeles.

Note: an earlier version of this article was published by X-TRA Online on August 15, 2021.