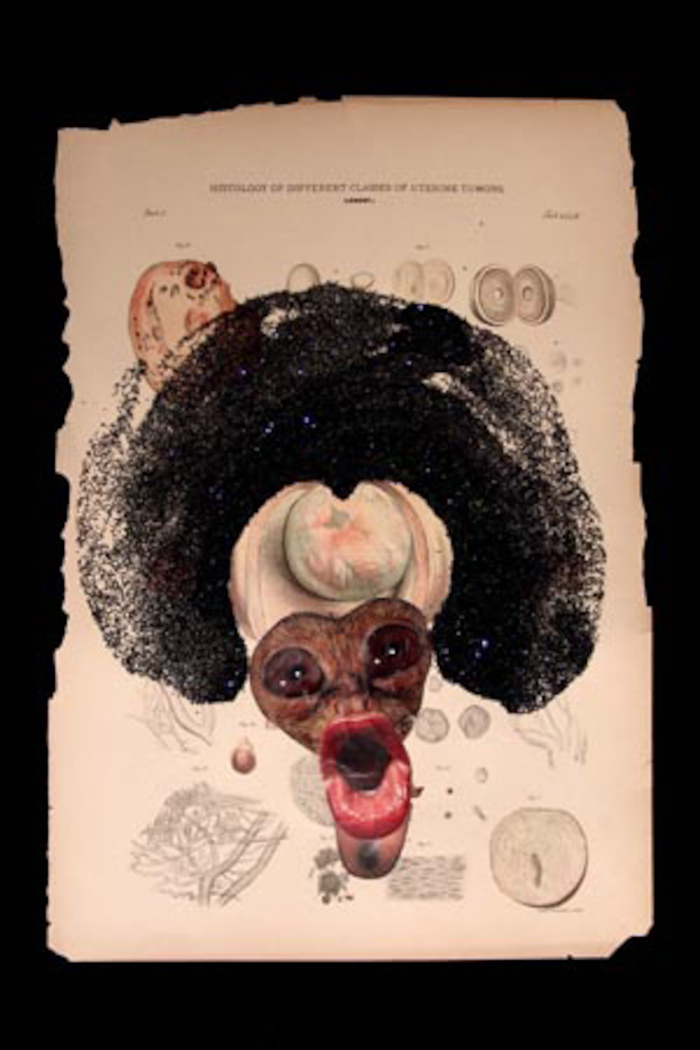

Even in Los Angeles, articulations of trauma in contemporary art are rarely as dazzling as they are in the sexed up sutures of Wangechi Mutu’s recent collage and wall works. Beyond appearances, however, the most beguiling aspect of her current practice is its precarious balance of effervescent surface and dire political connotation. In a suite of morbid and seductive montages, Mutu wagers that zero-sum codependence between the opulent visual impact of her compositions and their intricate political dimensions won’t melt down in a kind of critical inferno. While it is difficult to locate points at which formal finesse and cultural commentary might be said to begin or end in such work, this seems precisely to be its ruse. Thus setting a trap for those hoping for tidy conjunctions of the aesthetic and the political in contemporary art, in Problematica Mutu presented an array of delirious old school assemblages–exquisite corpses for a globalized era.

A catch-all category of classification for zoological specimens of unknown origin or affinity, the term problematica also refers to familiar fossils found in strata or locations in which they shouldn’t–according to received wisdom–be present. Mutu herself has previously been known to exhibit African artifacts of questionable authenticity, or rather, artifacts that parodied dubious cultural preconceptions about authenticity and origin. Perhaps as a response to similar traversals of incertitude that today seem generic in the work of artists belonging to a second or third generation concerning itself with postcolonial conditions, Mutu seems to favor cranking up this sense of uncertainty a notch or two. In exquisite material flourishes, luscious reconstitutions of female anatomy and acidic observations on the deficiencies of epistemological and cultural conventions in the West, her sassy figures trip their way through and beyond a history of postcolonial aesthetic strategies. While work made by artists practicing in related territories over the last ten years or so often seemed all-too-easily reducible to its message or political load, Mutu remixes the highlights of that decade’s focus on identity politics, center-periphery dynamics and critical reflections on Western aesthetic canons with a kind of dance-floor exuberance. Poco a go-go, you might say, is the way of the walk.

Mutu’s work is dense with allegorical references to a culture of origin in Africa, or more specifically, Kenya, so it’s easy to see it as representative of current practices by international artists negotiating clusters of aesthetic, cultural and political complexity typically aggregated under the rubric of postcoloniality. But, while many artists living in the Southern Hemisphere, Central and Eastern Europe or Asia might be said to be working under idiographic variations of such conditions, Mutu is based in New York and maintains a nonresidential relationship to the place that her work continues to evoke. She is one of a comparatively small but growing number of contemporary artists usually considered by the cultures in which they no longer reside to be expatriates or members of a diaspora. For artists such as Mutu, years (if not an entire adult life) spent developing a practice in metropolitan hubs located in North America and Western Europe introduce additional complexity to their postcolonial scenario.1 While a relationship to the metropolitan centers of colonial power has always been a constitutive dynamic of the postcolonial experience, unlike previous generations of expatriated or diasporic artists, Mutu’s proximity to places with which she remains culturally affiliated is no longer governed by traditional notions of geography.2

As glitter, dismembered and recombined fashion models or parts of machinery culled from magazines congeal with hemorrhages of ink, acrylic and other materials in Mutu’s collages on Mylar, they leave an unequivocal impression that the problematic nature of historical practices of classification with specific regard to African women are merely one part of their elaborate riddle. Mutu dovetails race, class and gender into forms that are such consummate paradigms of the critical deployment of hybridity3 through postcolonial discourse in recent times that they both anticipate and vault their own capture on the following terms: “Hybridity represents that ambivalent ‘turn’ of the discriminated subject into the terrifying, exorbitant object of paranoid classification–a disturbing questioning of the images and presences of authority.”4While classical applications of this term distinguish between colonial and indigenous cultures, locating hybridity in a productive friction between the two, Mutu’s work moves beyond 20th century models by hybridizing its nonresidential geopolitical foundations with those of the contemporary international art market. Her fantastic distortions then circulate as psychosexual apparitions in a market where the artist’s relationship to her culture of origin is refracted in the kaleidoscopic effects of her immersion in Western aesthetic and critical traditions. While the gritty art historical traction of the resulting work seems irrefutable in relation to Dada or Surrealist collage technique, what happens to the notion of politics in such a practice?

When Hannah Hoech and Hans Bellmer produced representations of disarticulated bodies in Germany after WWI, there was little ambiguity about the political scope of their aesthetic endeavors. Against the backdrop of an ascendant fascist cult of the body in Germany in the 1930s, Bellmer developed his work as an explicit affront to Nazi sensibilities. Hoech’s celebrated experiments with photomontage and the fragmented female figure, in addition to her satirical engagement with the sexism and fascism of her day, provide Mutu with a European avant-garde precedent for an aesthetic with ambitious political aspirations. More recently, South African-born Candice Breitz contorted ethnographic kitsch and pornographic representations of the female figure into post-apartheid non-sequiturs in her 1996 Rainbow Series. Breitz, discussing the political dimensions of her formal approach in that series of photomontages, asserted that, “Leaving the scars that mark the meeting of two contrasting bodies visible and untreated no longer has the shock value or political potential that it might have had in the early days of photomontage.”5How could it, she suggests, after similar techniques were utilized to erase difference in the name of global capital by Oliviero Toscani’s United Colors of Benetton campaign? When Mutu constitutes her creatures from snippets with a variety of racial attributes, there’s never a shortage of embellishment when they meet at a join. Ink or acrylic washes or painted edges carefully underlay and adorn such intersections in Royal Blue Tragedy (2005), exemplifying the artist’s approach to the legacy of her modernist and postcolonial predecessors: she invests heavily in an aesthetic play that neither disowns nor can be stripped down to pure political truths.

Perhaps conditions in Kenya are familiar enough to a Western public for them to skip from the mottled pathological lesions in the figure of She’s Egungun Again (2005) to a rising awareness of Kenyan HIV infection rates, currently estimated at 6.7% of the general population. One might leap from there to a correlation between the proliferation of the female figure in Mutu’s work, as a more detailed breakdown of that statistic reveals the infection rate for women to be twice as high as that for men. Similarly, it is possible to link a prosthetic device supporting the truncated limb of a traumatized figure in The Naughty Fruits of My Evil Labor (2005), to violence associated with conflicts on the African continent. Or perforations in the gallery wall that are an element of the site-specific installation Erasing Infestation — An Exercise in Historical Futility (2005) may recall the pockmarks that bullets leave in architecture during warfare. Because Mutu never explicitly invokes such political realities, however, her problematica boogie on a tightrope between the political possibilities of a realism that eschews any uncertainty about its subject and an allegorical hall of mirrors deflecting the political into its reconstitution within an aesthetic project. Mutu seems to solicit and then ward off critical inscription of an exclusively political nature, nesting iterations of the political inside the formal and aesthetic parameters of her practice.

When formal ambition and the question of politics operate within such a closed circuit in contemporary art, Jacques Ranciere’s relatively upbeat comments (for a contemporary French philosopher) on the metapolitics of aesthetics offer, I think, the most thoughtful description of a resulting dilemma. Ranciere identifies a strain of contemporary practice that “promises a political accomplishment that it cannot satisfy, and thrives on that ambiguity.” Alas, he concludes: “Those who want it to fulfill its political promise are condemned to a certain melancholy.”6 Mutu doesn’t break any such promises because she scrupulously avoids making them from the outset. If there is ultimately a melancholic quality to her creations, this is due to her capacity to phrase their evocations of contemporary suffering and trauma so beautifully.

David Hatcher is a nonresident New Zealand artist living in Los Angeles.