Note: This conversation took place in April 2020 when the coronavirus pandemic had indefinitely postponed McCollum’s retrospective at the ICA Miami. The exhibition was originally scheduled to close on July 19, 2020. As of this article’s publication in November 2020, the exhibition has been extended until January 17, 2021.

In 1967, Allan McCollum decided to be an artist. He remembers the precise day, he once told an interviewer, because the decision coincided with a heartbreak.1 In the ensuing fifty years, McCollum has achieved a staggering quantity of work. One paradigmatic “piece” from the late 1980s contains what the title indicates: Over Ten Thousand Individual Works (1987–ongoing). There are three versions. Later projects involve row upon row of casts of fulgurites, a kind of glass formed when lightning fuses soil or sand into a durable shape; dinosaur footprints and bones; and the titular Dog from Pompei (1991). Among other benefits, making art at this scale allows the artist to meet people and make friends outside of the art world’s narrow circles. Around the turn of the millennium, McCollum formalized this interest with The Shapes Project (2005–ongoing), which is an attempt to assign a unique 2-D form to every living person on the planet.

McCollum’s first US retrospective was scheduled to open at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, in March 2020. It was moving, he told me, to see his life’s work all in one place—to watch the connections between the canonical and the oddball play out across space and time. Then, with nearly everything installed—tens of thousands of casts, drawings, paintings, booklets, carvings, pieces arrayed in their impressive ranks—the coronavirus pandemic shut down the world. He will likely remember that day, too.

Allan McCollum: Works Since 1969, installation view, ICA Miami, March 26, 2020–January 17, 2021. Left: Collection of Plaster Surrogates, 1982/91, enamel on cast Hydrostone, dimensions variable. Center (background): Drawings, 1989/91, pencil on museum board, dimensions variable. Center (foreground): Perfect Vehicle, 1988, acrylic latex on cast glass-fiber-reinforced concrete, 80 × 36 in. Right: Untitled Paper Constructions, 1974–77, watercolor, ink, pencil, acrylic paint, glue, and paper, dimensions variable. Courtesy of ICA Miami. Photo: Zachary Balber.

TRAVIS DIEHL: Maybe we can start by talking about your retrospective at the ICA Miami, and where that stands.

ALLAN MCCOLLUM: Yeah, well, I don’t know. We got almost everything finished, then suddenly the museum had to close. All the staff was sent home and nobody could visit the museum. And to this day, nobody knows what’s going to happen, if and when the museum will reopen.

I was in a state of mind that I’d never been in before—kind of amazed at my own history, for better or for worse, because I’ve never seen all that work together, work from the sixties, seventies, eighties, right up to the present time. This is the first time I’ve had a retrospective in the United States, although I’ve had a number of them in Europe. And this is the first retrospective ever to include work of mine from the late sixties until the present.

DIEHL: I’m curious about the process of gathering all of these projects for the retrospective, which each have hundreds or thousands of parts. Were they sold as one work and kept together in that way, or were some works widely dispersed and more of a challenge to reassemble?

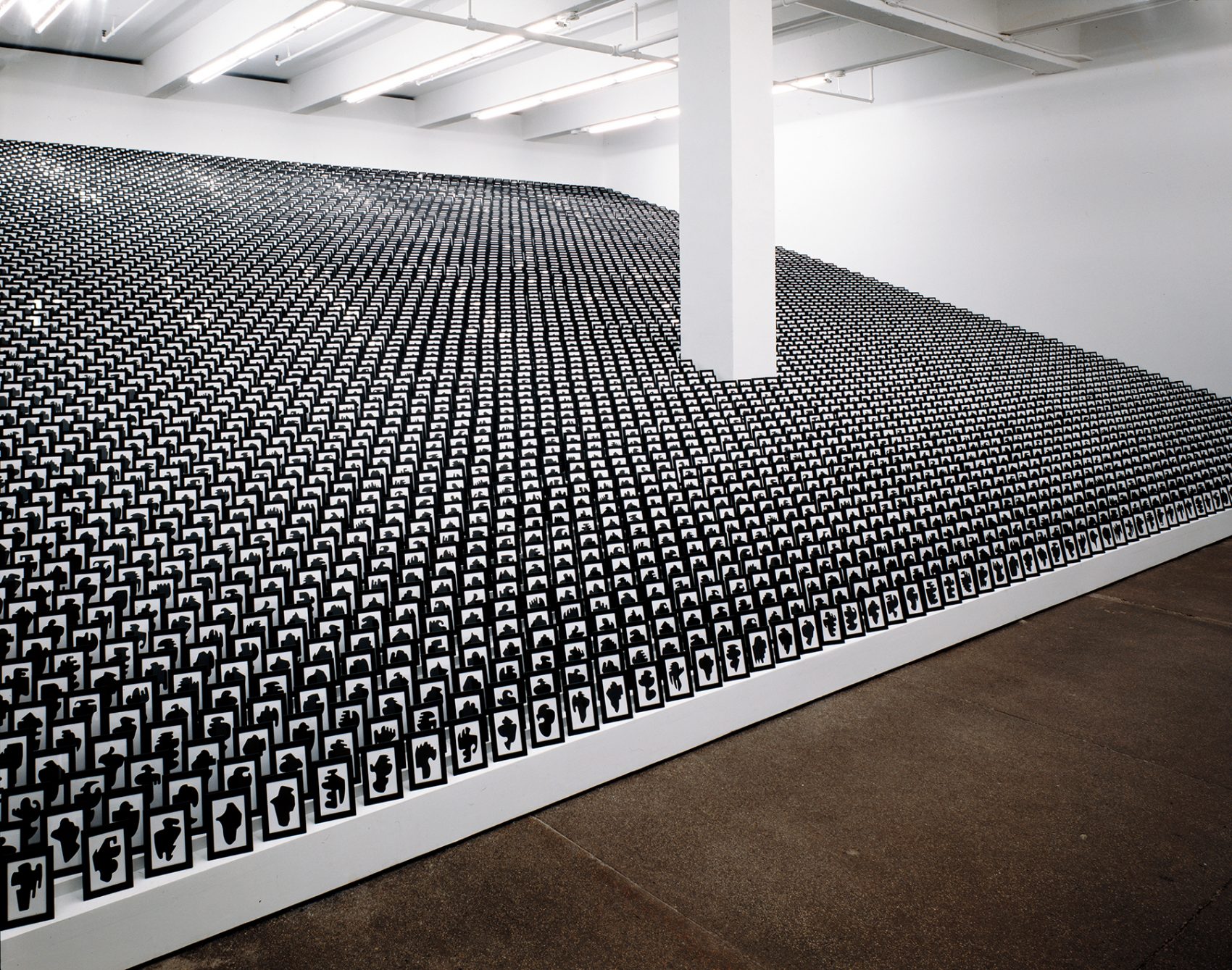

MCCOLLUM: I’ll tell you about Over Ten Thousand Individual Works. That was the first project where I made over one thousand things. I made over ten thousand objects, each unique, and I had been thinking you could buy one for $25. I was going to do the show with John Weber in New York, and halfway through my making of these things, he said, Allan, there’s not going to be 10,000 people who come in here and buy each one for $25. He said it takes as long to write a receipt for $25 as it does for $25,000. So, I said, Oh, alright, I’ll make a reference to factory work. I’ll put them in groups of a gross, 144. And you have to buy a gross. So, I got all these certain size boxes that just fit and boxed them all up in groups of 144. And then, once I put the show up, John said, Allan, we have to talk. You know, it’s “over ten thousand.” If somebody buys 144, there won’t be over ten thousand anymore. You have to think of this as a singular work and hope a museum buys it. In the end, he was totally right. I’ve made three different versions of that project, so I’ve made 33,000 or so objects. There are three different collections of Over Ten Thousand Individual Works in three different museums, and they are all unique. One of them is at MoMA [Museum of Modern Art], and they lent theirs to the ICA.

Allan McCollum, Over Ten Thousand Individual Works, 1987/1991. Enamel on hydrocal, dimensions variable. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Committee of Painting and Sculpture Funds. Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York. Photo: Larry Lamay.

But very few things in the show had to be borrowed from collectors or museums. We borrowed a number of Surrogate Paintings (1979–80) from Yvon Lambert in Paris, because he had bought almost all of them. And the Plaster Surrogates (1982/83), we borrowed two collections from two different owners. There were over one thousand works from my Drawings (1989/93) project in the exhibition, some from my personal collection. All of the older work from before the seventies I still have. The fulgurite project [THE EVENT: Petrified Lightning from Central Florida (with supplemental didactics), 1998], which contains 13,000 copies of sixty-six different booklets that I made and had printed and over 10,000 casts of a fulgurite, I still have all of those.2 I’ve never tried to sell them or donate them to a museum. So, I’ve got some things in the exhibition from my own storage.

DIEHL: Is that because, for example, THE EVENT is one piece, in the same way as Over Ten Thousand Individual Works?

MCCOLLUM: My concept was to repeat the idea of making over ten thousand things. I guess my problem is that I think too much about doing things that most people couldn’t buy. I mean, sometimes I try to make something that will fit over somebody’s couch, but I’m not very good at it. I did 750 dinosaur bone casts, working with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and that cost me a huge amount of money out of my savings. I went broke making them and only sold a group of fifteen, so I still have 735 dinosaur bones. Back then, the collections were just too huge for the average art collector to buy. But I’m used to that. I like having wide-ranging interests.

I was especially interested in the fulgurite project because, well, it was a project done regarding Central Florida in connection with both an art museum and a science museum in Tampa [University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum and Museum of Science and Industry]. The fact that fulgurites are produced in a fiftieth of a second amazed me, that objects that people collect are created in a flash, but then they last forever. They’re like fossils. I got involved with Dr. Martin Uman, a man I’d heard about who collected fulgurites. He is one of the world’s leading authorities on lightning, and he teaches at the University of Florida in Gainesville. He and I got together with the directors of both museums. Lightning is one of the ways Florida defines itself. It’s the lightning capital of North America; there’s more lightning in Central Florida than anywhere else in Canada, Mexico, the United States. You know, even the ice hockey team is the Tampa Bay Lightning.

DIEHL: For that piece, you collaborated with a team of scientists to produce a fulgurite, then had it cast thousands of times. The way the fulgurite project is installed at the ICA Miami, it has the rocket used to attract the lighting, as well as a container of sand and some of the other context. I wonder why you chose to include evidence of the process in that work.

MCCOLLUM: Well, I often have done exhibits that involve also displaying how the artworks were made. When I showed the fulgurites at the Petzel Gallery in New York, I also had notebooks to look through and all these little pamphlets you could read and things like that. I did a project called Perfect Couples (2005/12), where there are two shapes, painted different colors, pasted to a ten-by-ten-inch board, and then dozens and dozens of them on walls in different collections. But I also had notebooks on the table, so people could see why all the colors were chosen, each color sample, where the wood parts were bought, which of my assistants did what. Another time, I made a book where parts of the pages had what I thought of as recipes, with sidebars showing the details of how the works were made, as if it were a kit that you could buy and do yourself. Often, I’m seeking to confuse the idea of an art display with, say, an educational display or a display in a factory showroom or a trade fair.

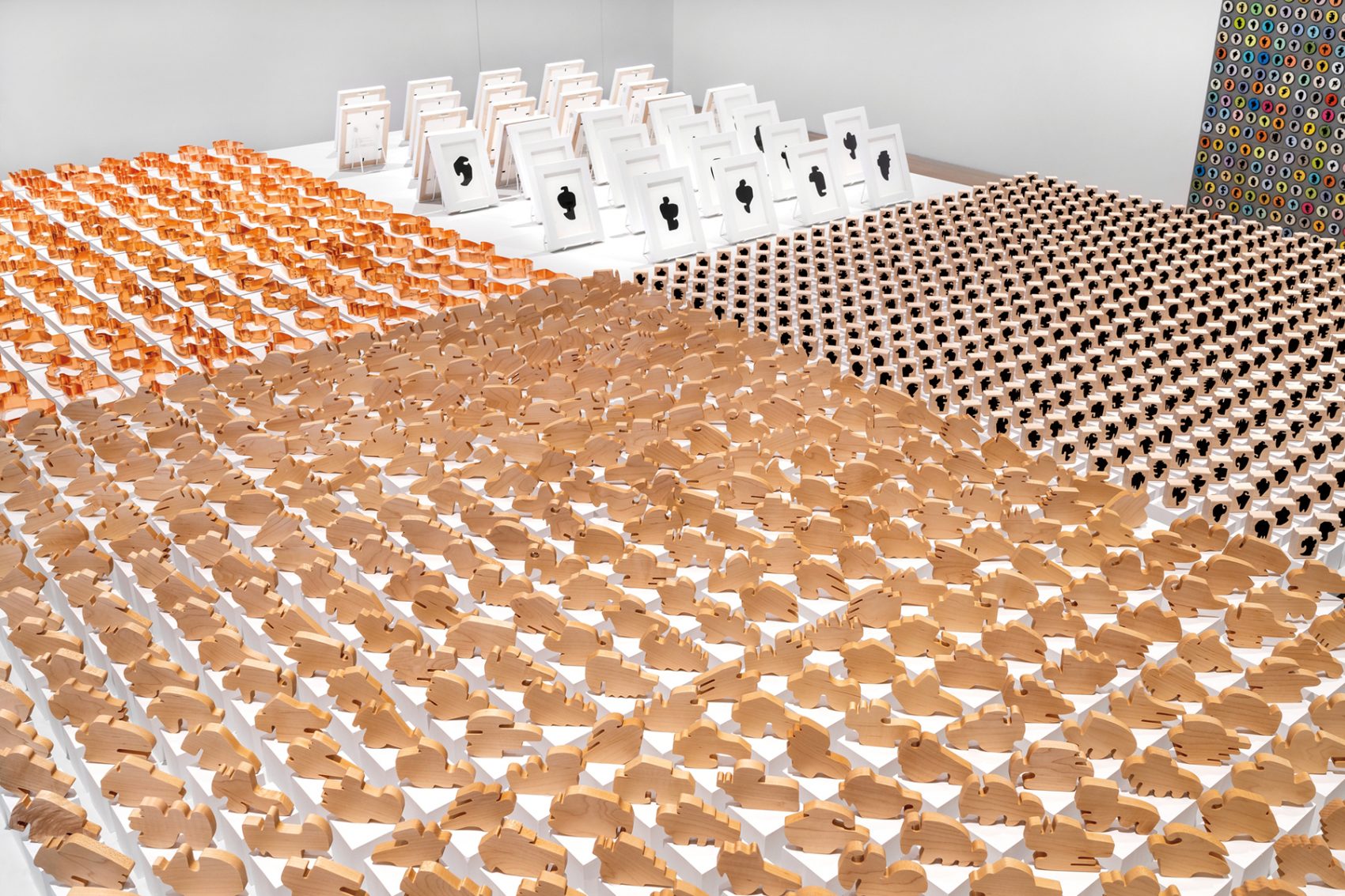

Allan McCollum: Works Since 1969, installation view, ICA Miami, March 26, 2020–January 17, 2021. Background: Drawings, 1989/91, pencil on museum board, dimensions variable. Foreground: The Shapes Project: Shapes Spinoffs, 2005, hand-lathed from ash wood, approx. 10 × 6 2/3 in. diameter each. Courtesy of ICA Miami. Photo: Wet Heat Project.

DIEHL: That seems related to a deliberate decision on your part, around 1990, to focus on areas outside of New York City, to make more “regional” projects.

MCCOLLUM: Yes, it was conscious. A lot of times you do things, but you don’t figure it out intellectually, in words. But I think I was feeling that the art world itself was way too focused on itself. Maybe that’s because I’m from Los Angeles, because everybody from LA knew that New York was avoiding them, you know? In the nineties, my work became very regional. I started doing projects all around the country based on community development, how people define their communities, how they come up with symbols that represent themselves. I did a project in Bend, Oregon, and small towns in Idaho and Maine, and actually over one hundred different little museums in Missouri and Kansas, and the fulgurite project in Central Florida. A project I did in Imperial Valley in California was based on their love for a certain mountain, Mount Signal, which was reprinted hundreds of times in ads and booklets and featured on badges and the county seal. I mean, people identify themselves with the town they live in, including people in Chicago and New York.

DIEHL: So, why not do a project like that in New York City or Chicago, something on a bigger scale? How would that work?

MCCOLLUM: I guess one could say that the fact that I’m an internationally known artist, blah, blah, blah, is one way of doing that in New York City, because that’s what they look for. But I’ve thought about it. New York is so complicated, in terms of how they think of their history, that it would be hard to come up with one thing. When I started doing The Shapes Project, I felt that could figure into the logic of any city, any town, because it was representing individuals. I mean, when I was in Imperial, California, talking to this woman, I think she worked for the city, I said, it’s amazing how many local artists paint the mountain. And she said, Well, of course they do. It’s the only vertical thing in the area. So, it was easier for me to think through smaller towns with more singular things. When people started towns in Imperial County, it wasn’t like New York, the history didn’t go back to Europe, they couldn’t call themselves new this or new that—New Jersey, New York, New Amsterdam, New England, whatever—so the towns had to come up with different ways of identifying themselves. Like the Eagle Rock neighborhood in LA, with that rock that looks like an eagle.

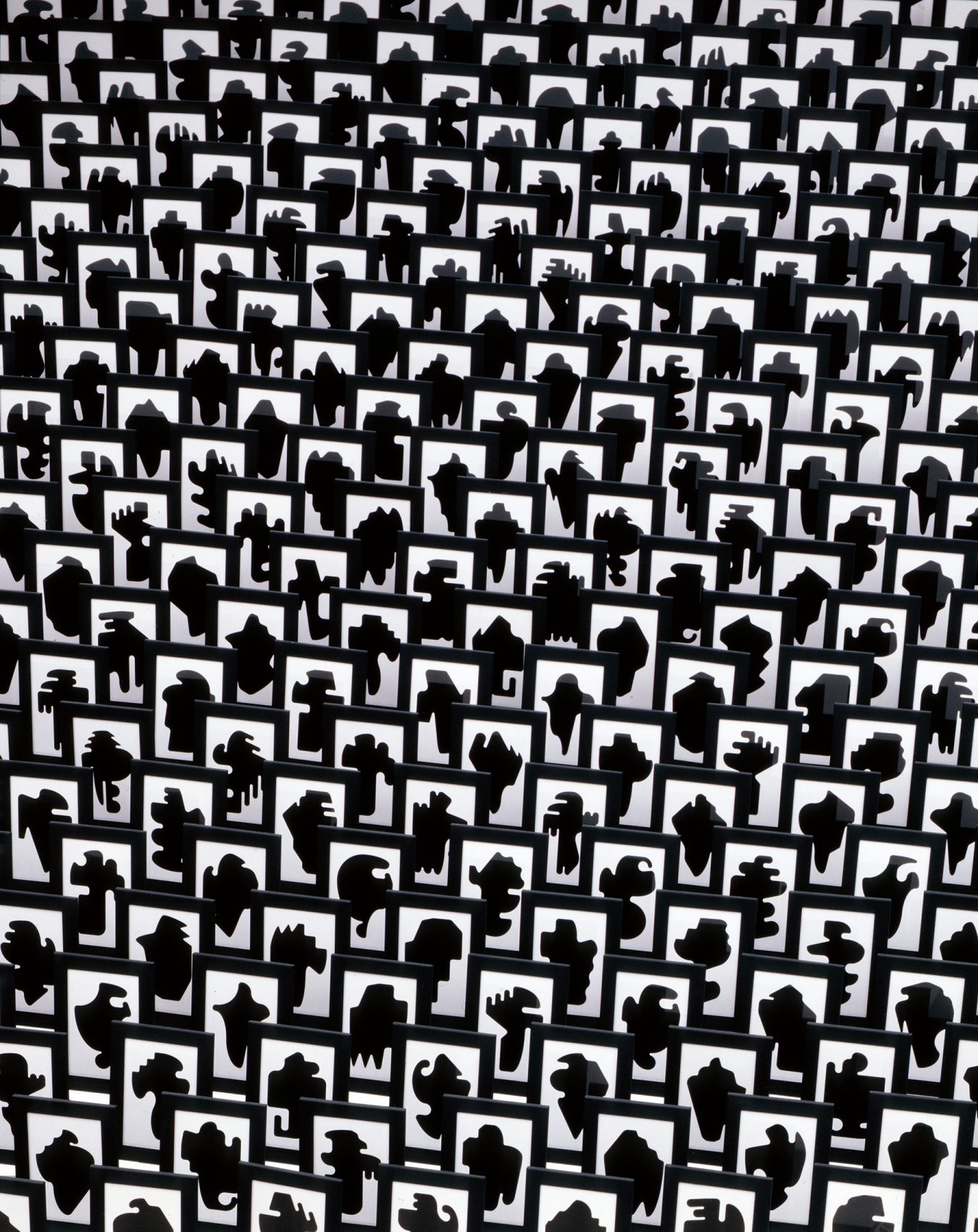

The Shapes Project, installation view, Petzel Gallery, New York, November 3–December 23, 2006. Courtesy the artist and Petzel, New York. Photos: Larry Lamay.

A lot of my research and production involves local people. With the fulgurite project, I was working with Margaret Miller, the director of the museum; she got the Tampa Bay Lightning to donate money to produce the announcements. This young geologist, Dan Cordier—who was a friend of the fulgurite collector, Dr. Uman—had built a model in his garage of how fulgurites were made, so we showed that.3 Dr. Uman was an artist also, a painter, and he had all these photos of lightning that he and others had taken. We put those in a reading room. The 10,000 fulgurite copies were made by a man and his son in Central Florida who had a little factory where they made sand-cast souvenirs like you see in souvenir stores.4

When I did a project about Mount Signal and the sand spikes in Southern California, I got people involved in Mexicali, Calexico, and Imperial Valley; my goal was to have as many people to thank as possible. Sometimes I would go and ask people for permission to use their logo when I didn’t really have to; I could have gotten the logo off the internet. But I would ask them, and they’d say, Oh, yeah, sure. And then I could put them on the list of people to thank. I made friends that way that I still have. I’m a kind of a loner, a lonely person, I always have been. I live by myself, never been married, have no children. I’m all by myself right now in this studio. So sometimes I try to heal myself by doing things like going around to 120 different historical societies and seeing how all these little local towns identify themselves and meeting the people and so forth.

DIEHL: I wonder how you think of yourself, your own practice, in those terms—I want to call it a cottage industry. You in your studio, making multiples—

MCCOLLUM: But I never use the word multiples. That usually means a limited edition.

DIEHL: Yeah. I’m struggling to find the word. Individual objects.

MCCOLLUM: Yeah. Things.

DIEHL: Yeah, things. But it seems like a similar economic model, a kind of home shop.

The Shapes Project, detail view, Petzel Gallery, New York, November 3–December 23, 2006. Courtesy the artist and Petzel, New York. Photos: Larry Lamay.

MCCOLLUM: Well, I do feel very much that way. And I’m sure many artists feel the same. Three-fifths of my “home” is just a studio, you know? I’ve always been interested in the context of art. We collect fossils, we collect flowers, we collect books, we save gifts that people give us. We save clothes. Art fits into a wider context of things we collect. And I was interested in how people make those kinds of things that aren’t considered artworks but which people buy and collect. I became interested in how people work in their homes and sell things online on Etsy and so on. For my project Shapes from Maine, I found all these small mom-and-pop operations that had ads on the internet, and I wrote emails to a number of people to see if they would make shapes for The Shapes Project using their own skills and traditions. And some of them were interested. Some of them weren’t. But they were all artistic in certain ways, like the woman who did the cutout silhouettes also was a portrait painter.5 The man who cut out the little wooden shapes, he’s also a preacher at the local church.6 The project was connected to how people find meaning in things and how “artists” aren’t the only ones who make and sell things based on their own tastes and interests. And it was fun. I mean, I guess I have to say it was fun.

DIEHL: How do you see the objects you make fitting into the ideas of class that are represented by the different kinds of collections you mention?

Allan McCollum: Works Since 1969, installation view, ICA Miami, March 26, 2020–January 17, 2021. Pictured: Shapes from Maine (Copper Cookie Cutters, Silhouettes, Ornaments, Rubber Stamps), 2008. Copper, acid-free black silhouette paper, New England Rock Maple, wood, and rubber, dimensions variable. Courtesy of ICA Miami. Photo: Zachary Balber.

MCCOLLUM: My work habits and my work processes grew out of not only having worked in a couple of factories and in some industrial food kitchens, which I did, but also from my memories of my mother and my grandmother making cookies and having us all decorate them, or making Easter eggs and coloring them, the kinds of things where you sit with people and make things together. And so, my projects pretty much turned into that, once I got into making the Constructed Paintings pieces in the sixties and seventies. I was having other people help me tear up canvas and sitting there and talking and chatting while doing it. My work is always technically pretty simple. It’s just that I choose to do it with intensity and time and quantity.

I also like the idea that nature produces copies. People tend to think of copies as being made by factories and so forth, and that only lower-class people have “copies” while upper-class people have “originals.” People like to think of nature as being something wonderful and beautiful, but I don’t think until DNA was discovered people ever really thought about nature producing “copies,” even though every leaf is different. Every pebble is different. The higher-class things are usually large sculptures or huge buildings, and in the lower class it’s postcards and posters. There’s a class system involved in all kinds of objects. There were many things I loved about Los Angeles, but one of the things I didn’t like about the LA art world was in order to succeed, at least back then, you had to be constantly going to parties, where rich people had art. I remember having this feeling that I had to sell my art to people who would never let me date their daughters!

DIEHL: This seems like a paradox in your work. I mean, earlier, with the Surrogates, you were making things that look like paintings, that circulate in a certain way. But, especially with the later projects, you’re seeking out these more vernacular objects, but the end result is still fine art.

MCCOLLUM: It’s a dilemma. Talk to Andrea Fraser about this. I mean, it’s in her head all the time. She wants to be critical about everything, but she has to bring attention to herself in order to do that. She’s an old friend of mine, and we have many similar feelings of, there’s no way this is ever going to work. It’s difficult to be critical of everything about the art world and be known at the same time. I mean, she’s lucky that she teaches at a university. But I don’t have that background.

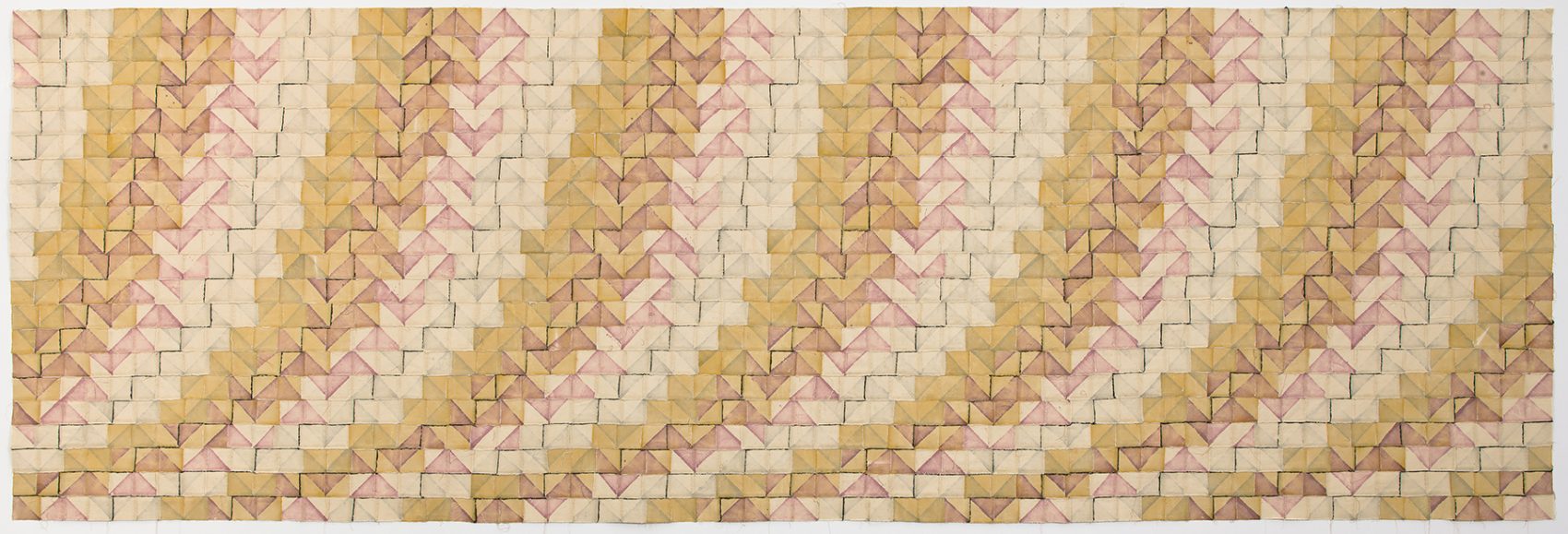

Allan McCollum, If Love Had Wings: A Perpetual Canon, 1972. Canvas, lacquer stain, varnish, silicone adhesive caulking. Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

DIEHL: That reminds me of an interview with you and Jeff Koons. I thought the two of you were kind of a funny pairing at first, since your work is so different. But it actually makes a lot of sense when I think about your relationship to class values. You say something to the effect of wanting to make so many objects that you would overwhelm the capacity of museums to store them all. I wonder if you have a sense of how that’s going. How many objects have you made in total, and how much storage space in the world is devoted to those objects at this point?

MCCOLLUM: Well, it’s sort of hard to estimate, but I use a storage warehouse in Brooklyn that’s about 2,300 square feet with fourteen-foot-high ceilings. And then I keep storage in a warehouse out in New Jersey, where I think I have 850 square feet. And then I have an archival apartment that’s only used as an office for my assistant and storage of paperwork. And then, in my own home, it’s a nightmare of storage.

What’s your question? How do I get the money? I’ve never had an expensive life. There’s something lucky about growing up in a poor family, you don’t have the same demands. I never had the need to buy fancy clothes or fabulous vacations or a car. I’ve always thought of that as an advantage. I’ve always put a lot of money into savings. I’ll probably have enough saved to maybe continue paying for storage until I’m 100 years old. Of course, I’ll die before that—the average American male dies at age seventy-six. In August, I’ll be seventy-six.

DIEHL: I don’t usually read people’s quotes to them, but I think this one is amazing. In the interview with Koons, you said, “I work out my own class anger, I think, by trying to produce more artworks than most museums have in their inventory.”7

MCCOLLUM: Okay, haha, that’s a good quote. I’ve no recollection of saying that. That was a quick interview done in a local SoHo bar, and I was probably trying to make the interviewer laugh. I mean, I must have said that because Jeff also clearly has an admiration for common objects that people buy for pleasure. One of the ways he describes some of his works is that they’re about “happiness.” His show Made in Heaven, at the Sonnabend Gallery in 1991, was all about happiness, and it included flowers, puppies, and him having sex with his porn actress wife, you know? Many different forms of happiness! He’s like a sociologist, in a way. I still admire him. I mean, I get so sick of reading people saying horrible things about him because he’s gotten rich, you know? I mean, so what? Lucky him. I don’t think he looks down on all this. I think he looks up at it and thinks it’s great.

I think that was the only time in an interview I ever used the word commodities, and it was because I was with Jeff. But in my mind, from the beginning of the human race, art objects were always exchange items. And when you look up the meaning of the word commodity, it’s items of exchange. It doesn’t mean factory things where there are millions of them. To say that commodities and artworks are different is to ignore the fact that artworks are made for exchange—for gifts or for sale—and people buy them.

I mean, one of the writers for the catalog for the ICA Miami retrospective is the wonderful art historian Jennifer Jane Marshall, and Jennifer has written a number of books about the differences between quantity production and artworks. She writes about art history between the World Wars. She wrote about how, during the Depression, many people hated the commodity market and factory-made objects, because it had taken away jobs from people who did handwork.8 The Ivory soap company invented this contest where you could get a big block of soap and carve a sculpture in it, and then there was a contest and an exhibition of the winners’ sculptures. They made handicraft a part of promoting themselves. There’s a history of people addressing the distinctions that people make between machine-made things, craft things, and things you buy in stores. I often say that when I walk into a grocery store, I feel thrilled, because I honestly imagine there were thousands and thousands of people who produced these things. There are the people who dug into the mines and brought out the metal that made the tin cans; there are people who developed the inks that made the labels. There are the farmers and the truckers who ship this stuff around. There are the packaging experts, the insurance brokers, the people who built the shelves. There are thousands of people. It’s like a chorus. Most people probably don’t think like this. And maybe especially art collectors, you know, because they send other people to do their shopping!

Travis Diehl lives in Los Angeles. He is Online Editor at X-TRA and a recipient of the Rabkin Prize in Visual Art Journalism.

Allan McCollum was born in Los Angeles and has lived in New York City since 1975. He has produced public art projects in both the United States and Europe, and his works are held in over ninety art museum collections around the world. His work has been included in numerous group exhibitions, including This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (2012–13); The Pictures Generation: 1974–1984, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2009); The 1991 Carnegie International, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh (1991); and the Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1975 and 1989). Survey exhibitions of his works have been held at the Musée d’Art Moderne Villeneuve d’Ascq, France (1998); Sprengel Museum, Hannover, Germany (1995–96); Serpentine Gallery, London (1990); Rooseum Center for Contemporary Art, Malmö, Sweden (1990); Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, the Netherlands (1989), and Portikus, Frankfurt, Germany (1988), among others.