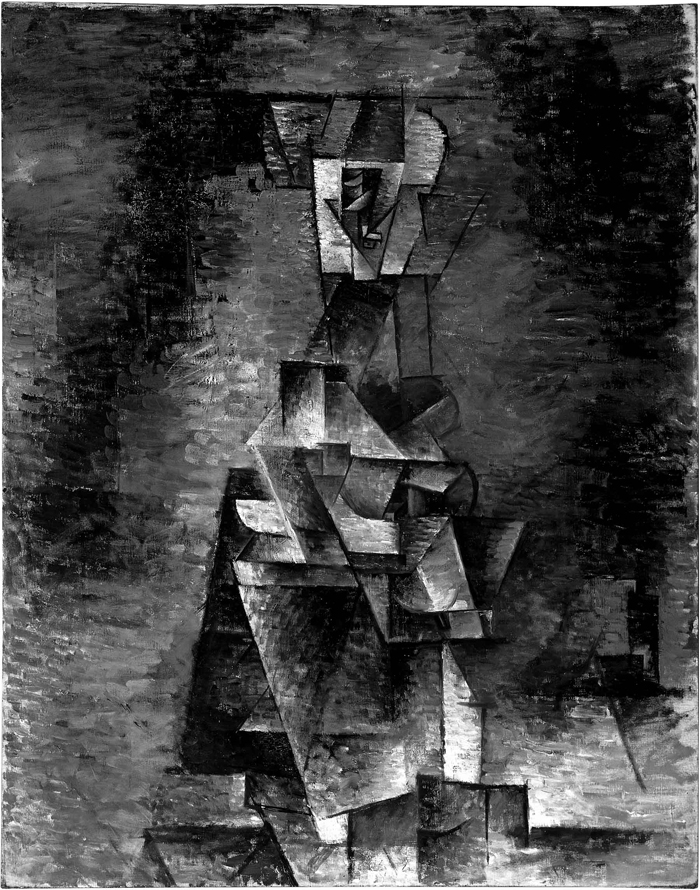

Pablo Picasso, Female Nude, 1910. Oil on canvas, 39-7/8 x 30-1/2 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950.

Upon entering Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism, the viewer is confronted by a hand-colored film of the celebrated American dancer Loïe Fuller. The flickering image is a kaleidoscope of unnatural pinks, blues, greens, reds and yellows that fluctuate in relation to the swirling of her voluminous skirts. In a career that spanned Art Nouveau to Modernism, Fuller enchanted audiences with performances that were augmented by the special effects of mirrors and changing colored lights—a multimedia experience of its time. She and her imitators were an obvious choice of subject when the cinematograph was introduced in 1895. Her performance—the constant motion of her shirts and her knowing play of hiding and revealing her body beneath all those yards of fabric—remains hypnotic and is crucial to the exhibition’s argument that it was film’s revolutionary and revelatory ability to capture physical movement that was the catalyst for the multiple perspectives of Cubist painting. This is a compelling premise that contends that the link between Cubism and early film is more conceptual than visual but it is ultimately mitigated by the exhibition’s positioning of film as separate from other forms of popular culture at the turn of the 20th century, as well as the emphasis on film technology itself and the lack of differentiation between the types of early cinema.

The exhibition features major cubist works by both Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque from a number of international private and public collections—none of which are for sale. A fascinating selection of long and short early films is also included. These are shown in a specially constructed Belle Époque “cinema” space of simple benches that references the disorientation of the original cinemagraphic viewing experience when films ran continually and viewers arrived and left by their own choice instead of following the dictates of the narration’s logic. However, by separating out the film of Loïe Fuller, exhibition curator posit it as more than just one more example of the type of films that Picasso and Braque would have seen in Paris in the teens. They conceive it as the catalyst for Picasso’s decision to “set painting in motion.”1Defining Fuller as a technological icon of eroticism and the perpetual movement of the new medium of cinema, they argue that the multivalence of Fuller’s cinematic persona delineated the possibilities of fragmentation and segmentation that Picasso explored in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907).2

This pairing is emblematic of the exhibition’s original premise that the relationship between early film and Picasso and Braque’s cubist paintings is not one of visual resemblance but rather of conceptual intent. That is to say that the advent of film created a crisis in seeing. Not only did film mix reality and fiction, its focus on movement challenged the way individuals understood the world and changed how they saw it. The camera’s viewpoint is single and indiscriminate as opposed to the human eye that constantly scans and reacts to what is in front of it. The argument is that after the advent of film, art was recast in terms of a filmic view and its function and process. This necessarily implied new ways of understanding and representing objects, motion, time and space on the canvas. Cubism, therefore, is defined as a system of analogies that overturned traditional and static visual signs and equivalences in favor of a different type of composition with new tropes and multiple and shifting points of view—each with its own separate spatial and temporal logics. The perfect example of this is Picasso’s and Braque’s papier-collé. Merging real fragments of paper and newspaper with elements drawn by hand, these compositions refused the traditional hierarchy of reading and understanding a work of art. They undermined their own illusionism by juxtaposing elements that contradict each other’s pictorial logic. This forced the viewer to engage with the work of art and make decisions about the relative importance of the composition’s individual elements. These works are, therefore, open to being read and reread according to where in the composition the viewer decides to begin. For Rose, this is analogous to the ability to stop and start a film Bernice Rose and art dealer Arne Glimcher in different points and to run it backwards as well as forwards.

Braque’s Mandora (1909–1910) is highlighted as an example of how a painting can function as a perceptual machine, creating different possible narratives and mimicking movement. The composition obviously represents a still life with the mandora at the center of a variety of objects. The round sound hole of the mandora is fractured into multiple points of view as is the instrument itself. This fragmentation is identified as more than a simple change in the physical perspectives from which the object can be viewed. Braque’s rendering of the mandora sound hole is equated to the camera lens itself. The composition’s choppy geometry and the instability of the elements around the mandora, which can seen either as objects in a still life or as architectural constructions in a landscape, suggest that the painting is a slice of a film stock with a number of possible narratives. In this way, the painting is seen as the producer of its multiple meanings—an actor rather than an object.

Affirming the importance of cinemagraphic technology to the paintings in the show, the exhibition includes a number of examples of vintage film apparatus. In the case of portraiture, direct analogies are drawn between the physical technology of film and Cubist representation of the human figure. This idea of the body as machine is certainly not new but in this specific instance, the visual reference to film machinery directly challenges any lingering formal readings of Cubist compositions as merely constructions of geometric shapes that grew out of the formal innovations of French painting by Manet and Cézanne, for instance. Picasso’s Portrait of a Woman (1910) is cast as a humorous assemblage of camera boxes and lenses. The figure is identified as both the camera and projector of her own image and accordingly, the emphasis is placed on her identity as a “camera/ woman”—subject/ object. This mixing of technology and sexual identity very pointedly brings us back to the dancing specter of Loïe Fuller who presided over the beginning of the exhibition and is at the genesis of the exhibition’s argument.

Nevertheless, this insistence on the physical appearance of machinery within the paintings also attenuates the show’s premise that the relationship between Picasso’s and Braque’s cubist paintings and cinema is not one of visual equivalence but of ideas and techniques. Like other arguments made for reading the distortion of light and space in some cubist portraits in the exhibition as similar to the flickering light of the film projector, this accent on visual correspondences reinforces the traditional approach to the subject of Cubism and film. This typically charts Cubism’s resemblances to the technique of rapid editing employed by such pioneering directors as the French filmmaker Abel Gance and the Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. This is not to say that these arguments do not have any merit—they obviously do. Gance’s use of mirrors to distort perception in La Folie du Docteur Tube (1915) and of rapid editing, superimposition, masking, and a wildly tracking camera in J’accuse (1919) present a similar multiplication of points of view that we see in Cubism. And who cannot think of the fragmentation of cubist composition when watching Eisenstein’s montage of shocks in his film Strike (1924) or the close-up of the splintered glasses of the nanny on the Odessa Steps in The Battleship Potemkin (1925)? However, the contribution of Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism is its theoretical approach to this relationship. Its premise is that early cinema profoundly affected the way individuals saw and understood the physical world around them and that this conceptual shock had a deep parallel influence on art in general and on these two artists in particular.3In response, the exhibition argues, Picasso and Braque represented reality in their cubist compositions as mediated and fragmented by different and sometimes completely opposing views.

For at least a decade, the definition of Cubism as a formalist movement has been problematized by extensive research into the topos and influence of its social, cultural and intellectual context. Analyzing the popular culture of the street, songs, music hall, reviews, press and publicity, writers such as Jeffrey Weiss and curators such as Kirk Varnedoe have shown how elements of popular culture were deeply ingrained in the avant-garde at the beginning of the century. Mass culture, as well as artistic parodies of it, influenced the public perception—and miscomprehension—of advanced art at this time. Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism follows in the vein of this research. Although in his essay for the catalogue film scholar Tom Gunning points to the fact that early cinema was initially part of vaudeville entertainment, the relationship of these sources is subtlety altered in the exhibition narrative.4 It is true, as Gunning states, that film kept alive and translated many of the traditions of popular culture and variety acts of the music hall. But the exhibition’s insistence on a hierarchical ordering of this relationship that places cinema as the most important influence on Cubism ignores the fact that Picasso and Braque were of a generation that intimately knew and enjoyed multiple forms of mass culture. It also ignores the fact that the relationship between film and popular amusements in the public sphere was contiguous in the early 20th century. They shared the same stages and the same audience. Indeed, given the technological limitations of early film equipment and lighting, early films were often conceived along the lines of staged acts with scenery, similar narratives and a static point of view. Therefore, to imply that film chiefly inspired the cubist elements of splintered vision and use of fragmented words and objects without citing the influence of other forms of popular culture is a hyperbole on the part of Rose and Glimcher. After all, as Weiss and other writers have demonstrated, the visual noise of urban Paris, complete with the jumble of half-obscured painted ads and poster advertisements, meant that fragments of words and phrases were a highly visible presence in the everyday landscape of these artists. Why would this jarring occurrence be any less of an inspiration to Picasso’s and Braque’s use of fragmented language in their cubist compositions than the presence of words in early films? Is it not more reasonable to think that the constant presence of disjointed language in the urban landscape, on the stage and in early cinema reinforced the impact of each of these sources? In this and other cases, the affect was probably cumulative, but this does not mean that cinema was not the emblematic catalyst of change.

Early film reflected the multiplicity of tastes, experiences and curiosity that early 20th century audiences brought to this new technology. The exhibition’s selection of film is fascinatingly broad but it can be faulted on two points. First of all, it failed to include one important type of early cinema. Early pornographic films made for male associations, bordellos and private connoisseurs are an essential part of this story. Although their absence may be understandable, their inclusion would have deepened the discussion of the cubist portraits (especially those portraits of women) as person/ machines able to act and project themselves into the world.5 This was a period of change in the identification and social roles of women. Socialism, suffragette movements and early discussions of birth control changed how women thought about their lives and their bodies.6 If the cubist portraits of women do portray them as hybrid person/machines that have ownership of their person and identity, surely sex is a key part of this discussion. This point was already highlighted by the exhibition’s founding definition of Loïe Fuller as an influential technological icon embodying eroticism and the idea of movement. In light of this, it is difficult to understand why a type of early cinema that specifically referenced sex would be ignored. Its inclusion, along with the attending problems of defining pornography as an exploitive medium or symptomatic of women’s sexual liberation, would have provided a compelling bridge to later discussions about the sexualized female machines of Dada and Marcel Duchamp.

Secondly, the exhibition’s non-differentiation of narrative films with costumes, scenery and backdrops from films that simply turned the camera on real life and documented habitual occurrences is a missed opportunity. Early cinema produced a re-enchantment of everyday life by focusing on the routine and banal as elements that were worthy of reevaluation and reinterpretation. This process of rendering the quotidian into something wondrous has a striking parallel in Cubism’s technical transformation of commonplace still lives and portraits—the standard subjects of European painting since at least the 17th century—into radical splintered images with multiple and simultaneous interpretations. Both early documentary films and cubist painting are mediations on real and everyday situations as new experiences on their own terms. This parallel has much to say about the modernist re-conception of lived experience through new technologies and machines that dwarfed the human scale or that could fly or propel the human body faster than it had ever traveled before, radically altering how individuals perceived the landscape around them. Early cinema’s influence on cubist painting is emblematic of that shift. It was nothing short of a revolution in perception and living and, far from reacting to these changes, Cubism was part of the process—forcing viewers to see and think differently.

In that early 20th century period of modernity, the shock of cinema cannot be overstated. Picasso and Braque responded with a dynamic syntax of motion on canvas that reflected the concepts and processes of film. Nevertheless, their approach would soon be superseded by other artists, just one generation younger, who would pick up the camera and begin making their own films. The intersection of film and art is a rich subject that is only beginning to be explored. Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism makes a bold contribution to this field. It is based on solid research and an interesting premise that did not need to be overstated. The conceptual leap it delineated speaks to the paramount influence of technology in the early 20th century. After the advent of film, Picasso and Braque could not look at things in the same way. Their powerful translation of the idea of polyvalence onto their cubist canvases is testament to their understanding of the momentous change happening around them.

Sara Cochran is assistant curator in the modern department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. She contributed to the catalogue for the Tate exhibition Dalí & Film and is currently organizing its showing at LACMA.