Louise Lawler’s Sappho and Patriarch (1984), a photograph of a statue of Sappho and a bust of a Roman patriarch, famously asked, “Is it the work, the location or the stereotype that is the institution?” Phantom Sightings: Art after the Chicano Movement is the first group exhibition of Mexican American artists at LACMA since 1974, and the largest such exhibition in LACMA history. It will be enjoyed by many schoolchildren, who will learn something about contemporary art, but who may not learn the deeper lesson, the answer to Lawler’s question: it is the work and the location and the stereotype that is the institution. Phantom Sightings is an institutional work: the show is about the art of making art history.

The exhibition is tightly curated by Rita Gonzalez, Chon A. Noriega and Howard N. Fox. Twenty-six artists are represented by 106 pieces of art, though the show is dominated by fewer than 10 of those artists, most noticeably Juan Capistran, Carlee Fernandez, Christina Fernandez, Ken Gonzalez-Day, Ruben Ochoa and Ruben Ortiz-Torres.

Both identity-based exhibitions and period surveys pose particular curatorial problems. Too much ordering becomes simplistic at worst, didactic at best. Too little runs the risk of individual works getting lost in the wash of history or watered down by the presence of the larger community. The Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution exhibit at the Geffen in 2006 dumped a generation’s process and product (approx. 120 artists, 400 pieces) into more or less uncut space with all the curatorial finesse of Costco. It was inelegant, an inelegance that was an elegant refusal to order feminist work. The times were messy; long live the times. Like history in the present tense, Wack! audiences had to forge their own ways and meanings from a glut of things unified only by threads of common experience. Individual pieces either held their own or fell unnoticed by the wayside. That so many of the pieces thrived amid such warehousing was testament to their charisma and the curator’s leap of faith. By comparison, the Phantom Sightings space has been carefully tailored with an eye for flow and against any sense of de trop. Too, unlike the sprawling muck of Wack! or the Brooklyn Museum’s Global Feminisms (2007), which included pieces such as Cathie Opie’s big fat dyke Madonna and child (Self Portrait/Nursing, 2004) and Ryoko Suzuki’s bloody facial Bind (2001), there’s nothing in Phantom Sightings to make the stodgiest uncle uncomfortable or flutter the feathers of anyone’s aunt.

According to the catalogue introduction, the goal of Phantom Sightings was to consider the emphasis in recent Chicano art (i.e. art after the Chicano art movement) on concept over representation and “social absence rather than cultural essence.” But the curators favor not dematerialized, high-concept works that might literalize Chicano cultural absence, but pieces of allusive representation, figural play and high craft. The exhibit is a palpable display of material essentialism. Every object is an object; almost every object is delightfully optical. Delightful in both senses–unrelentingly likeable and lush, and progressively less illuminating. Like a show-off god, Phantom Sightings wants to make up for all its omnipresent absence–what Harry Gamboa, Jr. (member of the 1970s Chicano art collective Asco (asco is Spanish for nausea) called the “phantom culture” of urban Chicanos–by way of representative excess.

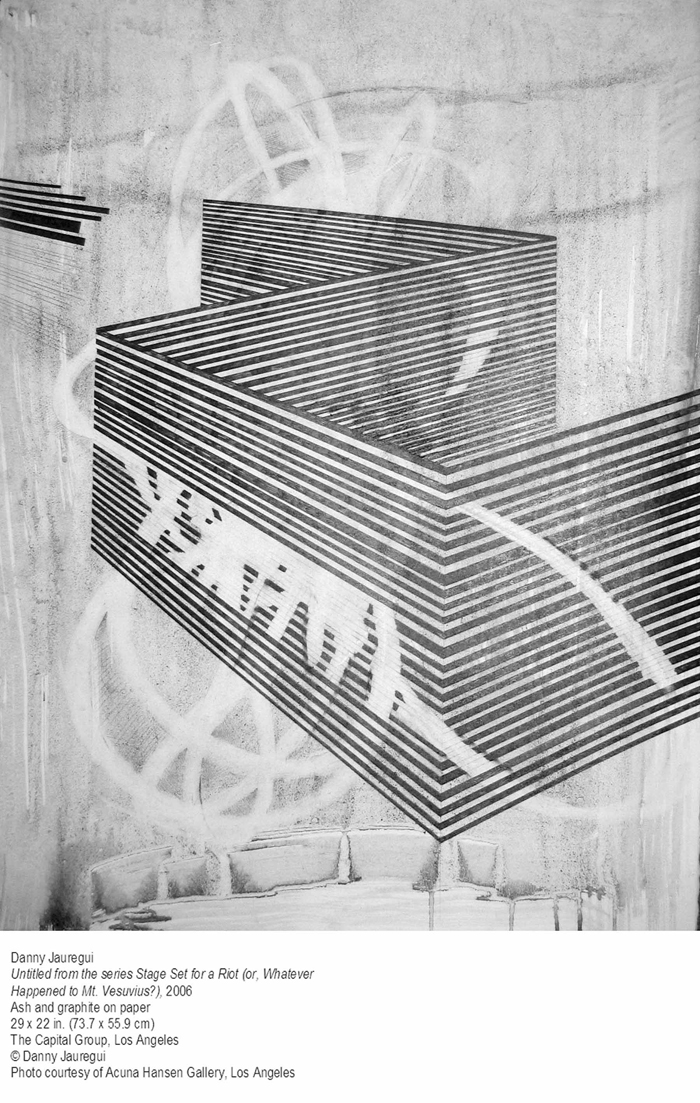

These excesses are chockfull of individual pleasures. There is the pleasure of the plane, such as the large landscape photographs of Delilah Montoya that depict in crystalline color abandoned migrant camps and desert water stations, sites where the landscape seems freshly scraped. What is left is the detritus–a pink backpack, a black boot, a plastic jug–the raw weep of the permanently dispossessed. There is the pleasure of the play of wit found in many of the pieces, such as Alejandro Diaz’s performance piece series Breakfast Tacos at Tiffany’s (2003), in which he stood outside the Fifth Avenue establishment with hand-painted cardboard signs such as “Mexican Wallpaper,” “Tacos 50c,” and (dressed as a mariachi player) “Available for Speaking Role in A Major Motion Picture,” transforming the acme of high-end consumer culture into just another store a guy could stand outside of hawking other stuff. And the pleasure of the two colliding, like Adrian Esparza’s Untitled (2006), gridded color lines emanating from or resulting in a hanging serape, happily weds folk craft to Sol LeWitt. LeWitt is echoed again in Danny Jauregui’s series Stage Set for a Riot (or, Whatever Happened to Mt. Vesuvius?) (2006), drawings that resemble slatted architectural sketches. Jauregui’s work is porous; his abstracted sides are open where LeWitt’s were closed.

Virtually all the pieces play with various antecedents, identified by the curators as other ghosts haunting the work. This eidolonic crowd includes the ghost of Chicano art, the ghosts of Chicanos who reject the demography, the ghost of the urban Chicano, and the ghost of the avant garde generally. In Carlee Fernandez’s Man photographs (2006), the artist possesses (thereby dispossessing) a series of male icons. Performing an Electral doubling of her dad, she puts on the same clothes, same cocksure stance, same small smile. Holding oversized stills of Dave Mustaine, Bruce Dickinson, Franz West, e.g., over her face, Fernandez’s body is dressed and posed to mirror the masculine (role) model’s postured head. She becomes a likeness of a likeness, a radical form of mirroring that, in this case, literally embodies the feminine within a masculine world of difference.

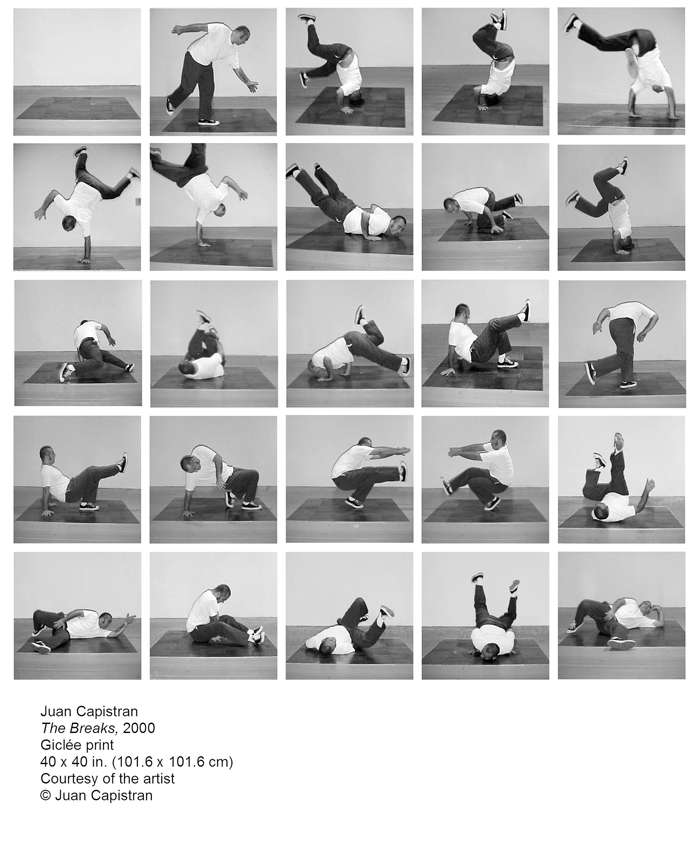

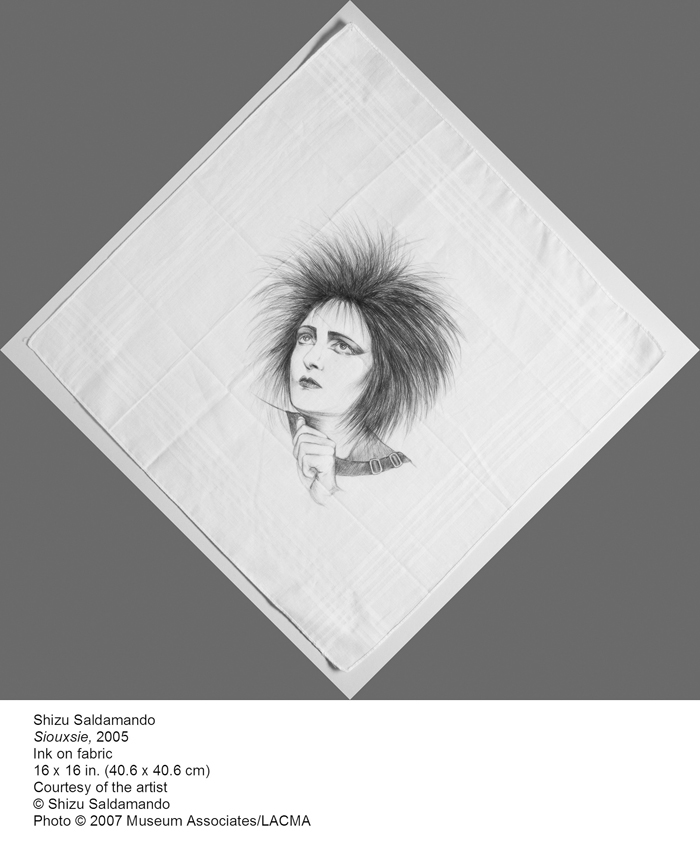

In his photo-grid The Breaks (2000), Juan Capistran breakdances on a Carl Andre (metal) floor sculpture. Unlike Rauschenberg’s de Kooning erasure, there’s no Oedipal anxiety betrayed in Capistran’s goofball baby brother routine. No art is harmed in the making of the art, and any artistic upset is due to Capistran’s casual commodification and the absence of any meaningful appropriation. It’s L.H.O.O.Q.-lite. By the same token, Margarita Cabrera’s soft sculpture vinyl VW Beetle titled Vocho (Yellow) (2004) is sewn full scale, right-sizing the People’s auto. If this does not exactly cut Claes Oldenburg down to size, it does put consumer culture in welcome perspective while conjoining ’60s Pop Art to Mexican factory work to ’90s indie craftwork in that post-identity art moment in which knitting, pie baking, and making duct tape wallets stood as markers of non-textual authenticity. The same enactment can be seen in Shizu Saldamando’s Goth punk version of arte pano (prison art)–portraits of Siouxsie and Morrissey done on cheap men’s handkerchiefs, standard prison keepsakes. The ephemera of two underground cultures collide, reminding us that our lives are spent making meaning out of transience, gathering our poor and personal souvenirs as proof of time served.

In “Allegorical Procedures: Appropriation and Montage in Contemporary Art,” Benjamin Buchloh wrote, “The allegorical mind sides with the object and protests against its devaluation to the status of a commodity by devaluing it a second time in the allegorical practice.”1 This second devaluation is ideally redeemed through the allegory’s new attribution of meaning; the redemptive function of allegory fails when the new meaning is no more or less than a recapitulation of the old meaning, or simply its horizontal extension. So Cabrera’s sculptures fulfill their allegorical function where Capistran’s montage does not–and Adrian Esparza’s appropriation of fliers used by the ’80s hardcore punk band the Minutemen as a critique of U.S. border policies (One and the Same [2005]) and Ruben Ortiz-Torres’s Smog (2006), boardroom-ready paintings done in luxurious lowrider Kamelon Kolors (props to Richard Prince), feel more like the triumph of the indie (quotidian + groove + technique = $$$) over the genuinely subversive. (Though this is not the case in Ortiz-Torres’s Urban Landscape [2006], where the 3-D extrusion of graffito done in a Kamelon Kolors copper-bronze works as a hard and fluid fold of materialized meaning and as an Eastside sotto voce to Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall.)

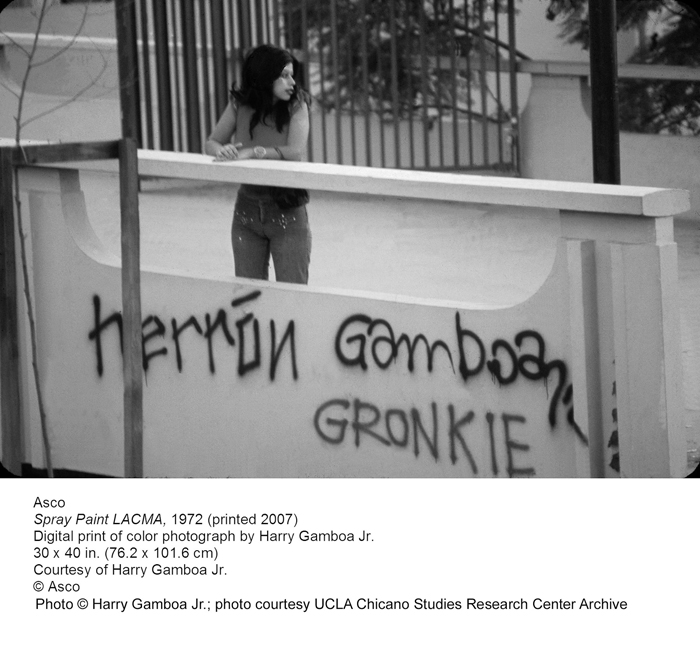

In a talk on the creation of the exhibit at the Los Angeles Institute for the Humanities, the Phantom Sightings curatorial team discussed their decision to jettison the term “action” for the term “intervention,” apparently on grounds that “intervention” has more current currency. Apart from logopoetic issues of animation–an action may be performed simply for the sake of the action, whereas intervention implicates functionality or utilitarianism–there are the questions of what is being interrupted, when the intervention occurs, and to what ends. Actions, according to this logic, become interventions to the degree that they retrospectively supplement the larger culture to the greater good. This may be accurate, but feels lousy, as the greater good mostly seems like tagalong sentiment: approval from a position of pre-approval. History has borne out the artistic viability of certain forms of street art, and therefore, we can, in an abundance of good feeling, acknowledge their viability. We like N.W.A. (Niggaz With Attitude) as artifact but don’t approve of the Crip currently at the corner, and condemn the war in Vietnam (though not those who fought or those who called them “baby-killers”). And in this snuggly vein, Asco’s Dadaesque protests have been transformed into comfortably-sized photos on the gallery wall. Asco’s appropriation graffito from the ’70s–signing members’ names to a LACMA exterior (Spray Paint LACMA, [1972, printed 2007])–is the exhibit’s first image. The 30″ x 40″ photographic print is activism as easel art, the movement removed from its confrontational corpus and freshly contained in conceptual cold storage. There is a Citibank ad where a kid paints a mural on the parents’ garage door while they are away. Luckily, Citibank’s cash-back program paid for both the repainting and “plenty of canvases for our son.” The ad header is “It’s hard to appreciate art when it’s not framed.” Just as with Asco’s Asshole Mural (photo of members flanking the maw of a sewer pipe) (1975, printed 2007), this shit is framed.

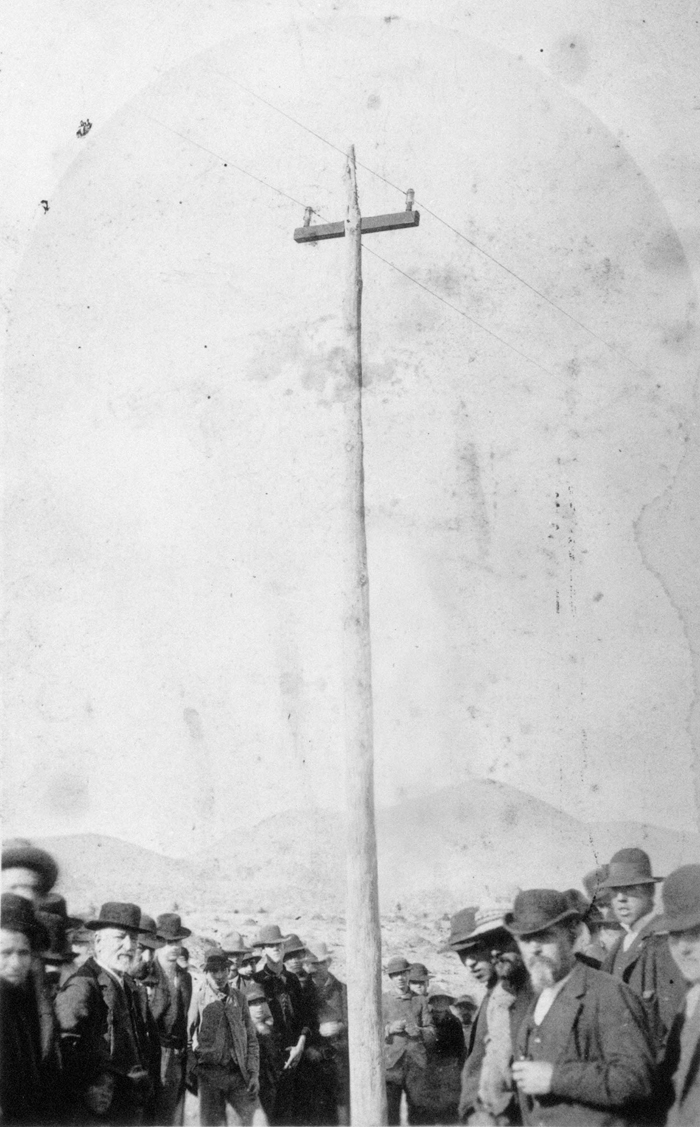

So the walls, historical and institutional, come tumbling down. And, too, the wall itself, site of Mexican high modernism, high/low art, border politics and gang throw-downs, is revised by several artists, most notably in the small interior hall supporting Ken Gonzales-Day’s lynching erasure works. Two large erasure images, the soft-hatted heads of a crowd of white folks milling around a conspicuously empty tree, have been placed along two temporary gallery walls. One wall is covered by a large blue/black print, the stasis of the site and the frozen, bruised moment underscored by the constricted palette. The mirror-image on the other wall is printed on mirror-paper. Gonzales-Day’s lynching erasure project surgically extracts the fulcrum-point of the image that the spectacle is supposed to mediate. In the wall/hall piece, the spectacle is recreated, thoughtfully leaving the viewer free to narratively participate as either victim or voyeur, depending where one stands. Some of us have more of a choice than others; still, there’s no dodging the implication of voyeurism in any respectable museum or historical retrospect.

Ruben Ochoa’s What if walls created spaces? (2006) is a lenticular print of a freeway wall as seen from across the freeway. The lightly-tagged wall fades out into an interlaced bank of dirt and grass as you walk towards the piece; walking in another direction causes the concrete to seamlessly reconstitute. It is a flat-out representational piece which undoes flat representation, becoming a meta-abstraction in which the plane of the wall is a screen, porous and fictitious, achingly beautiful, an allegory of melancholy and want. The modernist allegory, as Christine Buci-Glucksmann has written, was the site of baroque melancholy and the miraculous and dangerous feminine.2 The dilations and contractions in Ochoa’s work enact the origamic promise of open space, freedom abstracted, and the threat of closure, freedom obstructed, the folding and unfolding promise and threat of the constant shift in perspective and promise. Everything and nothing lie across the freeway.

This melancholic voyeurism eventually felt like the most politically powerful potential of the exhibition–the familiar, local Chicano peoples on friendly display, strung up in their own latency, against all our walls. A friend said she was not going to see the exhibition because she preferred her history in the Smithsonian. Another one said the show could have just been called “L.A.,” not the poolside Los Angeles of David Hockney or Joan Didion, but the asphalt cool of Brooklyn Avenue and backing beats. Between these two statements lies the discomfiting point that what the institution giveth, the institution taketh away. Phantom Sightings is an institutional work, an avuncular pat on the head, a move that necessarily effaces movement. At the LACMA shop, the show’s requisite tchotchke is a brown bumpersticker taken from one of Alejandro Diaz’s Tiffany’s pieces that reads, “Make Tacos, Not War.” It’s as anti-revolutionary a sentiment as nostalgia, as impotent an objet as a time-clock. For a moment, I wished it had said “fish tacos,” ruding up the old hippie slogan. But then there it was–the melancholic feminine moment, the point where the wall of the institution, being a wall, effaces, giving way to something that is crude and alive, and in this rawness, capable of something that perhaps cannot be finally institutionalized.

Vanessa Place is a writer, lawyer, and co-founder of Les Figues Press.