Jin-me Yoon, Long View, 2017. Still from single-channel video. Courtesy of the artist.

Born in Korea and living in Vancouver, lens-based artist Jin-me Yoon’s foremost concerns are environments interwoven with empire. Since the 1990s, her photography has combined documentary capture with scrupulous staging, drawing formal parallels with the Vancouver School of photo conceptualists such as Stan Douglas and Ken Lum, whose highly constructed approaches to image production have frequently focused on Vancouver’s social history, resource industries, and property development.1

Yoon’s breakthrough work A Group of Sixty-Seven (1996) meditates less on the physical space of Vancouver than on the symbolic landscapes of Canadian art history, specifically artists associated with the Group of Seven. In that piece, Yoon produces passport-style portraits of members of the Korean-Canadian community, with paintings by early twentieth-century artists Emily Carr and Lawren Harris serving as backdrops. Carr and Harris are a conspicuous choice here: both received extensive support from Canadian political and cultural institutions eager to establish a modernist tradition at home.2 With their thick deployment of curved lines and bold forms, their paintings not only monumentalize Canada’s mountains and rainforests but also depopulate them. A Group of Sixty-Seven critiques this alchemy of transcendental landscapes and racial purity that permeates Carr’s and Harris’s paintings by foregrounding the relations between the Asian subjectivity and Indigenous land that those paintings—and the national mythology commonly associated with them—otherwise suppress. Yoon reworks what Iyko Day theorizes as settler colonialism’s triangulation of “symbolic positions that include the Native, the alien, and the settler,” each of which are unevenly mediated by access to (or denial of) territorial entitlement. Discussing A Group of Sixty-Seven specifically, Day argues, “The jarring superimposition of Asian faces onto the constructed landscape also serves as an invitation to consider why Asians have or have not been incorporated into the dominant social and cultural landscape in Canada.”3

Over the intervening thirty years, Yoon’s emphasis has shifted from a deconstruction of Canada’s fictional landscapes to an embodied engagement with empire’s material sites of transit and occupation. Her photographs and moving images feature warships on the horizon, concrete wreckage interspersed with wildflowers, and oil terminals poking out of thickly forested hillsides.

Jin-me Yoon: About Time, the exhibition catalog that accompanied Yoon’s solo exhibition of the same name at the Vancouver Art Gallery last year, pairs her works from the preceding decade with essays that frame her project around questions of temporality and settler colonialism. In book form, About Time invites readers to engage with Yoon’s work as a visual index of everyday life’s extractive edges.

Examining Yoon’s videos Long View (2017) and Mul Maeum (2022), Susette Min describes Yoon’s project as “a ‘deep dive’ and ‘deep dig’: a mode of decolonizing empire and diasporic nationhood in relation to hospitality, stewardship and care.”4 Her text concentrates on Yoon’s portrayal of the Pacific Ocean as an entity that both impels migration and separates people across space and time. Like Min, Anne-Marie St-Jean Aubre underlines how Yoon’s artworks address the environment not in terms of a static landscape but rather as a contact zone for “the interconnectedness of all forms of life.” Just as important, Aubre’s commentary notes that the individuals in Yoon’s photographic works are not “extras” but rather friends and family of the artist, a decision that “destabilizes and complexifies the clinical aesthetic that is generally associated with her conceptual approach.” According to Aubre, Yoon celebrates “human relationships that led to the exploration of our interconnectedness with nature” while also exposing “the histories that haunt symbolic sites which opened into a broader understanding of the notion of temporality.”5

Jin-me Yoon, A Group of Sixty-Seven (detail), 1996. Chromogenic print, 19 by 24 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Curator and scholar Ming Tiampo expertly situates Yoon’s visual practice in the context of Canadian, specifically Vancouver-based, art. She makes the case that where “Vancouver School Photo-conceptualism . . . seeks inclusion into existing Art Historical narratives,” Yoon’s early photographic works “question those narratives and their claims, and prompt the viewer to ask themselves: who is Canadian? Whose land is this?” Shifting from A Group of Sixty-Seven to the more expansive geographies that characterize her recent projects, Tiampo stresses that Yoon engages in “not just a critique of Canada, Canadian multiculturalism and Canadian Art History, but more fundamentally, a critique of colonialism, which she understands as a structural and a transnational issue.”6 One of the more stirring claims in the catalog comes from Sharon Kahanoff: “[D]ecolonization cannot happen without first reconceptualizing time itself.”7 In Kahanoff’s argument, Yoon develops a series of formal practices and aesthetic objects with which to conduct this reconceptualization: the ready-mades and abandoned film sets Yoon photographs become visual mustering points that weave together the past, present, and as-yet indeterminate future.

These essays and another by Tarah Hogue productively use settler colonialism to frame Yoon’s project and discuss how her artworks “create the conditions upon which a different future could be built,” to use Kahanoff’s words.8 Yet the physical forms of resource exploitation and private property these artworks critique is given less focus. More specifically, while the catalog essays have plenty to offer regarding Yoon’s aesthetics of time, they have virtually nothing to say about Yoon’s peculiar oil spills in This Time Being (2013), the huge oil terminals and tankers in Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways) (2022), or the hydrocarbon-consuming city in The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul) (2006).

I want to dwell on these artworks (and others like them) for two reasons. First, they confront our complicated reliance on fossil fuels in ways that reject the dominant visual trends of lamentation and sublimity that typify much petroleum-critical art.9 Second, and connected to the first, these images address one of Yoon’s central questions—“What is our relationship to [A]boriginal people in contemporary Canadian society?”10—by highlighting how the relations between Indigenous land and settler capitalism are rendered visible and, more importantly, lived. As Yoon makes clear, to carbonize is to politicize. Her representations of oil radically rethink the space and time of settler colonialism, where stolen land links as much to resource exploitation and real estate in Canada as it does to the global capillaries of plunder and trade.

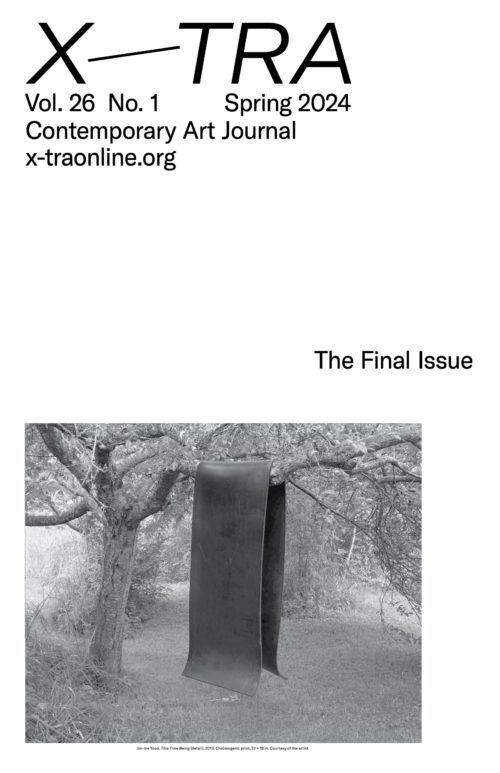

Jin-me Yoon, This Time Being (detail), 2013. Chromogenic print, 18 x 22 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Consider This Time Being, a series of sculptural portraits whose principal figure is a large rectangular sheet of black rubber. In an image that occupies the double-page spread between Diana Freundl’s “Curator’s Introduction” and Tarah Hogue’s opening essay, the rubber material is draped over a tree branch. About Time doesn’t specify the proportions of the rubber itself, though in this image it measures about double the length of the nearby tree trunk, and is maybe two inches thick. Clover and turf carpet the ground, while leaf shoots and tall grasses fill the background. Closer to the tree trunk, a twig reaches partway toward the viewer, little tufts of lichen dangling from its arm. Although the scene is densely packed with flora, it doesn’t feel claustrophobic: light splashes from without. The final endpapers of the catalog feature another image from this series, where what appears to be the same rubber sheet lies crumpled on a stony beach. As an abstract figure, it calls to mind trash, building material, flooring, conveyor belts, assembly lines. A darkened void, it sponges the viewer’s gaze while refusing to cohere into a stable representation. The iterative structure of This Time Being allows Yoon to continually recast the rubber in relationship to its surroundings. Placed beside the sea, the rubber’s slick black surface mimics an oil spill. But this simulation is imperfect, insomuch as its solid form proves an unconvincing petrochemical disguise. Compared to the greenery and shoreline in each image, the rubber suggests an industrial aberration, but one that is nonetheless pliable enough to meld with its surroundings. Is it destructive, or just disjunctive?

Jin-me Yoon, This Time Being (detail), 2013. Chromogenic print, 22 x 18 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Disjunction typifies the experience of any exhibition catalog, due to the limits of editorial selection and the process whereby diligent close reading relaxes into random page turning. This feels especially relevant in the context of Yoon’s book, largely owing to its design and structure. Double-page spreads containing blown-up film stills often punctuate the space between essays. These reproductions omit page numbers, and their captions precede them by several pages, implying that the images’ function isn’t strictly referential but also gestural. The catalog opens with a flurry of spreads that run for just over twenty pages: a heron leaping into the air, infrared imagery of clusters of pink spaghetti, archival footage of a parade, digitally cloned soldiers swarming a beach. The montage concludes with several reproductions from This Time Being. The links between these images are left unstated. Yet, by extricating This Time Being from its original context—the serial form and the gallery wall alike—the catalog brings the questions of oil’s ubiquity to bear on the entire breadth of Yoon’s recent output.

On a material level, the hydrocarbon-based synthetic rubber that Yoon uses in This Time Being both dominates its environment and accommodates itself to it. The sculptural figures in these photographs attract our attention even as they passively flop on the shore. They evoke the sludge we probably all picture when we think of oil, yet they also invite a larger array of connotations—industrial, ecological, and extractive.

The sculptures can be thought of as “synthetic real forms,” a term Kahanoff uses to describe the props that Yoon regularly employs in her art. Of the brightly painted rocks included in Yoon’s installation Untunnelling Vision (2020), Kahanoff writes that the forms “have a ready-made sensibility and are poppy, playful, or recognizably fake.” For these rocks, “signification is less important than the way they put the past, present and future into relation with each other.”11 Kahanoff doesn’t discuss This Time Being’s rubber sculptures in conjunction with synthetic real forms, but I think the interpretation applies. Placed in a series of alien environments, the ready-mades in This Time Being emphasize their extraction and transportation from one context to another. These synthetic real forms are not direct manifestations of industrial machinery or raw materials; rather, they evoke the relations between source, transmission, and endpoint. A hypothesis, then: the very elasticity of these sculptures—their figural capaciousness, which fails to coalesce into any representative signifier—provides a visual analogy for the seemingly infinite dispersion of petroleum-based polymers, from the single-use plastics that fill our homes and hospitals to the maritime oil trade that buoys the global financial system.

Over and above ecological grief, This Time Being’s curious dissociation of an oil spill—whether strewn on the beach or suspended from a tree—uses abstract sculptural figures to conjure the abundance of petroleum precisely when it isn’t otherwise apparent in the landscape. The catalog more broadly demonstrates that, at least in the Global North, there are very few instances where oil appears before the naked eye. Nonetheless, Yoon encourages us to think with and through this social invisibility. Her work considers not the sublime representation of oil but rather our relationship to the world it produces.

Land is a crucial component of that relationship. Consider the fortification of oil that appears in Yoon’s photographic series Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways). Although these striking portrayals of petrochemical megastructures occupy a considerable amount of space toward the catalog’s end, they are virtually unremarked upon in the essays. Distinct from This Time Being’s indirect evocation of oil, Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways) confronts the mother ship itself. In the foreground, figures clad in black appear mid-dance on a beach at low tide. In the artist’s words, these photographs “portray youth of Korean ancestry, many of whom are biracial, carrying other histories in their bodies.” Their dynamic poses recoup “the traditional Korean crane dance to depict diasporic subjects in flight.”12 According to Hogue, this takes place “at the Maplewood Flats Conservation Area, a former industrial site located on sәlilwәtaɬ (Tsleil‐Waututh) territory.”13 In one reproduction, a dancer is silhouetted against the reflective glare of wet sand. A tanker looms in the distance. Toward the top right of the image, a condo and a building crane rise from the hilltop, the latter serving as the mechanical mascot for Vancouver’s relentlessly booming real estate economy. The double-page spread immediately preceding this reproduction contains a photograph from the same series that combines a coastal landscape with a sprawling oil refinery, one of its gas flares lit up like a monolithic candle. On the beach, a child gingerly steps barefoot across the silt. Similar to A Group of Sixty-Seven, this photographic project resituates Asian subjects in relation to Indigenous land and settler enclosure. But where Yoon’s earlier work used Canadian modernism’s landscape tradition as the basis of its critique, Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways) contemplates the lives located around and displaced by petro-modernity.

Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways) juxtaposes two forms of transit. With the Korean crane dance, these figures can be seen re-embodying deeper histories of migration, whereas the oil refinery underscores the far-flung frontiers and infrastructures connected to colonial resource extraction. These “machine-in-the-garden” images map the human figure onto both the afterlives of dispossession and the largely invisible global relations of energy and finance.14 Yoon underscores Vancouver’s status as a resource colony, less a city of corporate glass than a city of petroleum pipelines. Here, migration and settlement dovetail with oil-reliant capitalism’s oceanic flows.

We could think of the terminal here as being entangled, thematically if not literally, with the city of The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul). In this video, Yoon straps a skateboard to her belly and arduously rolls through quotidian environs of South Korea’s capital city from one embassy building to another. Doing so, she calls attention to the country’s historical position between two empires by subjecting herself to a durational and laborious journey that ties its political institutions together. In one frame, a police officer gives Yoon’s scuttle a perplexed glance. In another, she drags herself past a 7-Eleven, a multinational corporation—headquartered in Texas and owned by Japan-based Seven & i Holdings—that distills the geopolitical relations that Yoon traverses.

Jin-me Yoon, The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), 2006. Still from single-channel video. Courtesy of the artist.

Rather than recite the dollar value of exports between Canada and South Korea, Yoon’s work in About Time embodies the long-distance relations suturing these two geographies.15 Here is where the color black takes on another degree of significance. It is not that the rubber sculptures in This Time Being and the tenebrous costumes in Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways) and The dreaming collective all maintain a superficial resemblance to the molasses-like slop normally associated with crude oil. Rather, their visual likeness and regional dispersion, from Vancouver to Seoul, appears to engage with fossil fuel’s complex spatiality. The same costuming features in the chromogenic prints and single-channel video work Long View (2017), most notably when Yoon stands on a beach looking out on a Turner-esque seascape. With her back to the viewer, Yoon’s gaze mimics our own. The video still freezes time, allowing us to hold that gaze for as long as we want. We’re looking at the same thing, but what is it?

I began this essay by saying that About Time indexes the extractive edges of daily life, but we could just as easily call them colonial edges. The coastlines portrayed by Long View and Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways) identify one such edge, where Yoon spotlights the trade routes and national borders whereby global capitalism and settler colonialism intermix and reinforce each other. The dreaming collective highlights how these edges are endemic to “metropole,” the figure in enlightenment philosophy used to contrast the city, as civilized center, with the “periphery,” thought to be uncivilized. For Yoon, the meaning is twofold: the colonial edge is both the sharp point of historical violence and the infrastructure by which contemporary life is held together. Yoon recognizes that our lives are edged, often constrained, by colonial forms of resource exploitation. But her art also fosters ways of seeing and relating that explicitly challenge these material and cultural enclosures.

Jin-me Yoon, Long View, 2017. Chromogenic print, 33 x 55.5 in. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery Acquisition Fund.

About Time documents Yoon’s patient and persistent study of imperialism’s spatial histories. Situated yet centrifugal, the works reproduced within the book address our petroleum-soaked lives while holding open spaces of solidarity. The catalog, then, is both an opportunity to encounter Yoon’s astonishing art and a provocation to grapple with the historical force fields that constitute the world as we know it: fossil-fuel dependency and environmental collapse, mobility and forced migration, belonging and racial violence, and colonization and the afterlives of empire.

Sam Weselowski is a poet and essayist from Vancouver, Canada. His most recent chapbook is Triple Rainforest (Veer2, 2023). He lives in the West Midlands, United Kingdom.