Installation view of the Brain at Fridericianum, dOCUMENTA (13), 2012. Photo: Roman März.

In October 1943, the city of Kassel was bombed by the British air force. The bombing targeted dense areas of workers’ housing, the crucial rail hub, and the Henschel factories that produced tanks, locomotives, and aircraft for the Nazi war machine.1 On the 2nd and 3rd of October, 547 airplanes bombed the locomotive works and an ammunition depot in the outer suburbs. On the night of the 22nd of October 1943, 569 planes returned, to hit the city center. “The 416,000 incendiary bombs fell in a density of up to two per square yard, thanks to the high-precision marking.”2 Most of the dead were asphyxiated in the firestorm that ensued, as 90% of the city center was destroyed.

Approximately 10,000 people were killed, mostly civilians and wounded soldiers recovering in local hospitals. Some accounts state that over 50% of the dead were women and children, as at this stage in the war, most of the men were mobilized in the military.3 The city burned for days; more than half the people of Kassel were left homeless. When U.S. forces finally took Kassel in April 1945, there was house-to-house fighting, and eventually the dramatically reduced population surrendered. At this point, 70% of the city’s residential buildings were in ruins.4

Downtown Kassel was re-built in the 1950s, and historic landmarks like the double towers of the church of St. Martin (which had provided a key visual reference point for the R.A.F. bombers) were re-duplicated in a 1950s architectural style. By 1955, the Museum Fridericianum (1779) was not yet completely restored, yet it became the central location for the art exhibition, documenta, which started as an adjunct to the national horticulture exhibition (Bundesgartenschau) that was held in Kassel that year.

From its beginning in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust and war, I see documenta as a project that was future-directed, both acknowledging the extreme trauma of the very recent past, yet implicitly presenting modern and contemporary art as a possible means of working through that history. The first documenta in 1955 specifically showed artwork from the Nazi Degenerate Art Exhibition of 1937, and focused on European art from the first half of the 20th century, including artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Piet Mondrian.5 An international discourse around art and culture was brutally suppressed during the Nazi era, and documenta was intended by its organizers both to acknowledge the interruption and to begin the conversation again.6

It is against this historical background of devastation and re-building that dOCUMENTA (13) was presented. Questions of memory, destruction, retrieval, and dislocation circulated through the exhibition. Ethical questions around curatorial procedures are central to the discussion of the show: artistic director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev (b.1957, U.S.A./Italy) commissioned most of the work in the exhibition, leaving room for artists to figure out what they wanted to make and show. This ceding of control to the artists was crucial to the overall tone of the exhibition; a fundamental feeling of openness, buoyancy, and playfulness allowed viewers room for discovery. Nevertheless, one of the largest spaces in the Fridericianum held only a glass vitrine containing a five-page, handwritten letter from German artist Kai Althoff (b. 1966) to Christov-Bakargiev, in which he explains he cannot participate in the show; he regrets deeply that this is the case; he knows he will never be asked to be in another documenta; he knows he wasn’t supposed to talk about being included unless he was certain he would participate, and he has only spoken to a few people, but he worries that even a few people is truly terrible. Most of all, he describes the pressure and anxiety that he feels, and this is why he cannot participate, despite his enormous respect for her and for her project.

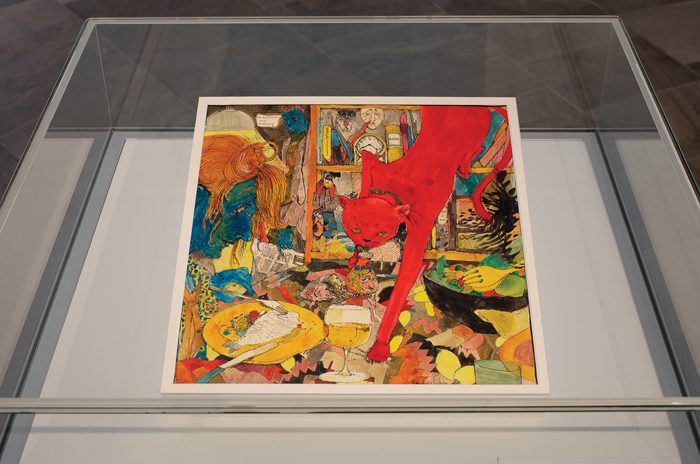

I read the letter having moments before seen Althoff’s work inside the “Brain,” in the central Rotunda of the Fridericianum. In other words, I read it knowing that the curator must have somehow overcome his terror and his guilt, and persuaded him to give her something to include. It was a brightly colored ink drawing of a red cat and a blue woman eating dinner; I couldn’t see why it was included in the Brain, the inner sanctum of this gigantic exhibition, until I read his letter, and recognized the depth of Christov-Bakargiev’s understanding. It’s possible that every artist in the show had moments of intense anxiety and experienced a wish to flee, similar to the feelings described by Althoff, and along with his cat drawing, his letter stands in for all of them.

Christov-Bakargiev assembled the odd collection of artworks and objects she called the Brain inside the Rotunda, a small glassed-in space where no more than forty spectators were allowed at one time. Protecting the Brain from crowds meant there was a constant queue, and I was glad to be advised by the doorkeeper to come back between 6:30 and 8:00 p.m., when the numbers dropped dramatically. As a result, I spent most of the first day looking at the rest of the show, and therefore the Brain (when I saw it at the end of the day) resonated in ways that wouldn’t have been possible if I hadn’t already experienced a significant part of dOCUMENTA (13). Rhymes and echoes of other works bounced around inside the Rotunda, drawing connections through and across the larger exhibition. In a sense, the Brain resembled a cabinet of curiosities, a set of miniatures, and in this way made reference to the history of the Fridericianum, which was one of the earliest purpose-built museums in Europe.7 The Brain offered all sorts of things to its visitors: ancient objects (Bactrian Princesses) next to unrecognizable objects (melted statues and artifacts from the bombed National Museum in Beirut) next to ordinary objects (a brick that represented the possibility of a radio in Czechoslovakia in 19688).

Kai Althoff, A drawing to Ms Rosalie Friedberg and her cat Red Oscar, 2012. India ink, watercolor and metallic ink on paper; 11 x 11 inches. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Henrik Stromberg.

Korbinian Aigner, Apples, 1912–1960s. 402 drawings in gouache and pencil or watercolor and colored pencil on cardboard; 4 x 6 inches each. Courtesy of Historisches Archiv der Technischen Universität, Munich. Photo: Roman März.

In contrast to the openness of the overall exhibition, which was enormous, multifarious, and full of surprises, both pleasant and otherwise, the Brain was intensely curated. It felt like a precise selection of objects, each of them extremely important to Christov-Bakargiev, and in her introduction to the Brain in The Guidebook, she placed her cards on the table:

The many threads of dOCUMENTA (13) inside and outside Kassel are held together precariously in this “Brain,” a miniature puzzle of an exhibition that condenses and centers the thought lines of dOCUMENTA (13) as a whole.… It speaks about our relationship with objects and our fascination with them.… There are eccentric, precarious, and fragile objects, ancient and contemporary objects, innocent objects and objects that have lost something; destroyed objects, damaged objects and indestructible objects, stolen objects, hidden or disguised objects, objects on retreat, objects in refuge, traumatized objects, transitional objects.9

In The Guidebook, the first artist that appears in the alphabetical sequence happens to be Korbinian Aigner (1885–1966, Germany), whose work was included both in the Brain and also in a large room upstairs. Aigner was a pastor who spoke out in his sermons against Hitler and refused to baptize babies with the name Adolf. In 1941, after a period in prison, he was sent to Dachau, where he worked growing medicinal herbs in the garden. He had a lifelong obsession with growing apples, and managed to develop four new breeds of apple during the four years he was in Dachau, which he named KZ-1, KZ-2, KZ-3, and KZ-4, KZ being the abbreviation for Konzentrationslager, concentration camp. Perhaps even more extraordinary, his passion for apples produced more than 900 small paintings of different kinds of apples, and a few pears, from the early 1910s to the 1960s. Each painting was about four by six inches, and for dOCUMENTA (13), a selection of 372 paintings was placed side by side in simple frames, in grid formation, calling to mind the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Most of the paintings show two apples against a horizon, one with its stem upright, the other upside down, leading me to suspect these may actually be portraits of a single apple, placed in two positions, to show off both sides. It’s an apple archive: each painting is numbered and they are all the same size, as if to be kept in a box like index cards.

In Aigner’s work, repetition, minimalism, and seriality were transformed into persistence of vision, as the belief in a future represented by this almost incomprehensible practice took form and was sustained over fifty years. I was struck by the simplicity of the apple (see Genesis, see Yoko Ono, see Apple), which seems almost to function as a representation too fundamental for interpretation. Only KZ-3 is still grown, and since the 1980s it is called Korbinian; one of Christov-Bakargiev’s contributions to dOCUMENTA (13) took the form of Korbinian apple juice bottled and sold at all the stalls and cafés around the exhibition. With a label designed by Jimmie Durham (b. 1940, U.S.A.), signed bottles sold for forty euros in the gift shops, and both a Korbinian apple tree and a Black Arkansas apple tree were planted in the Karlsaue Park, an eighteenth-century landscape garden, in a collaborative work by Durham and Christov-Bakargiev. In this way, a memorial was initiated: to the dead, to the almost unspeakable history, to the ones who survived, to things that continue to grow.10

Horst Hoheisel, Aschrott Fountain, 1908–2012, Kassel. Photo: Nils Klinger.

Horst Hoheisel, documents of Aschrott Fountain, 1908–2012. In photograph: fortune coin and work glove from the cleaning of the Aschrott Fountain, Horst Hoheisel with Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, March 29, 2011; historic photograph, 1908, courtesy Stadtarchiv Kassel; recent photograph, 2012; and two assignments for service and maintenance from the city of Kassel to Horst Hoheisel, 1988/2012. Unless otherwise indicated, all works courtesy the artist. Photo: Henrik Stromberg.

Also in the Rotunda were photographs and drawings by Horst Hoheisel (b. 1944, Poland) for Negative Form, his 1987 anti-memorial to the monumental fountain originally donated to the city of Kassel in 1908 by Sigmund Aschrott, a Jewish philanthropist and city planner, and destroyed by an anti-Semitic mob in April 1939. Standing outside City Hall, and designed by the same architect, its obelisk was twelve meters tall, with a stone basin of water below. After World War II, the remaining indentation became a municipal flowerbed; then in 1986, a competition was held to redesign it. At this point, Hoheisel proposed and constructed an inversion of the fountain, in which the obelisk disappears as a shadow of itself, under the city street, a “negative-form monument” or mirror image of the original.11 Water pours into a void, a hollow, inverted obelisk, twelve meters deep, making a sound that invites passers-by to stop and wonder. Each month from March to November, for the last twenty-five years, Hoheisel has cleaned out the inverted fountain, removing both the trash and leaves that accumulate, as well as the coins people throw in. Christov-Bakargiev put on rubber gloves and helped him with the cleaning process, and the residue of this activity was placed in the Rotunda, alongside Hoheisel’s drawings and photographs, marking her participation in an action that itself speaks of the artist’s persistence and dedication. The passage of time is marked by the action of cleaning the fountain, constructing an artwork that remains almost invisible, a shadow of itself.

The Brain also presented a painting by Mohammad Yusuf Asefi (b. 1961, Afghanistan), who worked as a conservator of paintings in the National Gallery of Kabul. Under the rule of the Taliban, paintings with realistic representations of humans or animals were ordered destroyed, being contrary to Islamic law. Asefi managed to preserve a number of paintings by pretending to conserve them; using watercolor to paint out the figures, the paintings appeared to be landscapes. It was a kind of camouflage, making the marks that obliterated the figures blend into the background, rendering them invisible. When the Taliban fell, he merely washed the watercolor off the oil paint, and the figures re-emerged. In this way, he protected eighty paintings from destruction. Asefi’s artwork, shown in the Brain, was itself a small landscape showing a dramatic river, mountains, and sky.

Very nearby, in the small space of the Rotunda, one encountered six quiet paintings by Giorgio Morandi (1890–1964, Italy) and around the corner, a selection of bottles, vases and an oil lamp, some of which were recognizable in the paintings. A black-and-white photograph of Morandi’s studio showed a shelf covered in similar bottles and vases. Remembering his perseverance in making these repetitive paintings throughout the period of Italian fascism raised the question of retreat and withdrawal as a means not only of survival but also of possibility.

On the floor, two stones were placed side by side, one a stone taken from a river, the other a copy of it made of Carrara marble, the whole a work titled Essere fiume 6 (1998) by Giuseppe Penone (b. 1947, Italy). The doubling of the stones made me think about the history of natural objects displaced in the museum, about the time-and space-warp that can occur when things are re-located in this way. It was impossible to be certain which stone was made by the river, which made by human beings, and this uncertainty worked to undo the received idea of a stable relation between a real and a copy, a before and after. Calcium Carbonate (ideas spring from deeds and not the other way around) (2011) by Sam Durant (b. 1961, U.S.A.) was placed on the floor nearby. Resembling a bag of marble powder, yet carved out of a solid block of Carrara marble, it extended the conversation to connect the ancient history of the quarry to contemporary industry, which transforms the stone into a commodity like any other.

Five original bottles Morandi had in his studio. Courtesy Museo Morandi, Bologna. Photo: Roman März.

The Brain invited us to think about representation and memory. On the 29th of April, 1945, Dachau was liberated by the U.S. Army. On April 30, 1945, Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide in the bunker in Berlin. On that day, Lee Miller (1907–1977, U.S.A.), working as an embedded photojournalist for Life magazine, visited Dachau. Later the same day, she spent the night in Hitler’s apartment in Munich, where she was photographed taking a bath, by her companion, David E. Scherman (1916–1997, U.S.A.). In these photographs, her heavy army boots sit clumsily by the bathtub; her eyes look to the side, as she wipes her neck with a washcloth. When they left the apartment, Lee Miller took a towel embroidered with the initials AH, a large perfume bottle, a framed photograph of Hitler, and Eva Braun’s powder compact, almost as souvenirs, and these very objects are placed in the Brain, in juxtaposition to the photographs of Miller. We can consider the expression on her face: she looks stunned, as if the coincidence of absolute horror at Dachau and the luxury of a warm bath were simply incomprehensible. Or maybe she’s just tired. In The Guidebook, Christov-Bakargiev is quoted as seeing this image as an “indirect photo of the camps.”12 I would suggest the entire project of the Brain is itself an indirect recollection of the history of fascism.

Aigner’s apple paintings next to the bottled apfelsaft, the newly planted trees; Morandi’s paintings next to a few from his collection of bottles and vases; photos of Lee Miller showing her with the objects she stole, and kept, carefully, that they may be placed on display now, thirty-five years after her death. These things require something of us: the artwork cannot remain in a space of aesthetic or intellectual consideration; history becomes undeniable, contaminating and interrupting the space of the imaginary with fragments of the real. Hoheisel described his anti-monument in this way: “It is not a place to put flowers.”13

Lee Miller, Lee Miller in Hitler’s Bathtub, 16 Prinzregentenplatz, Munich, Germany, 1945. Courtesy Lee Miller Archives. Photo: Lee Miller with David E. Scherman © Lee Miller Archives, England 2012. All rights reserved.

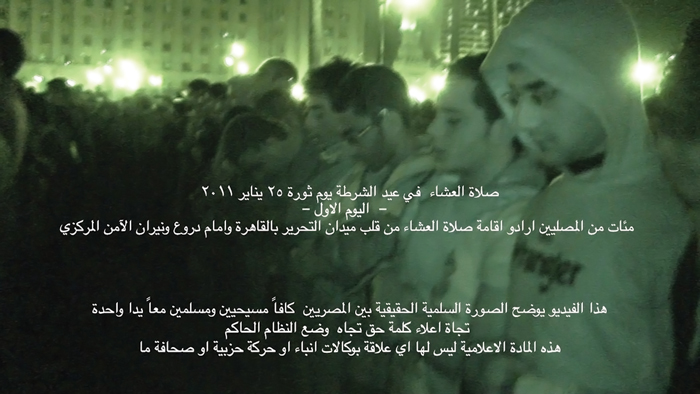

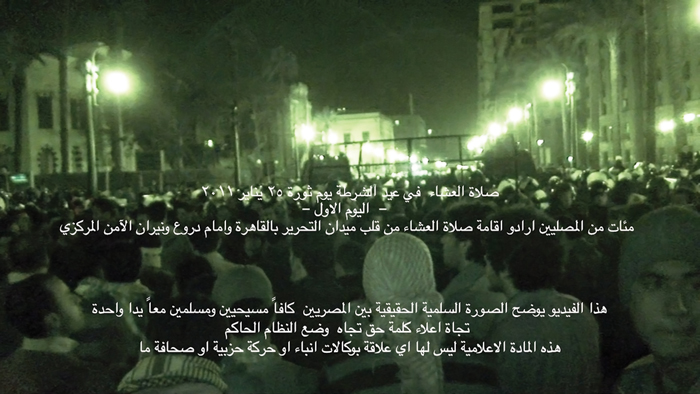

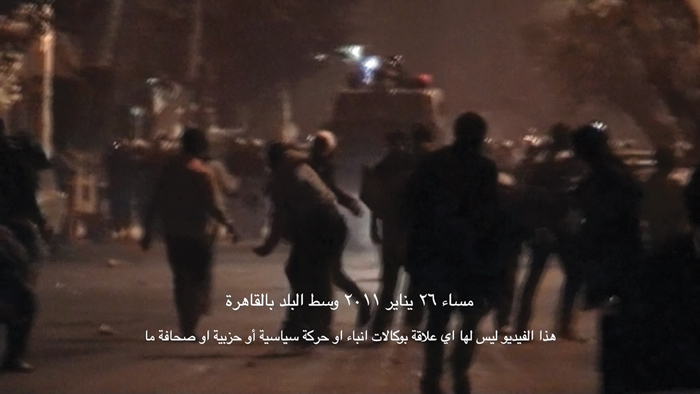

A small laptop in the Brain presented the YouTube video posted on January 25, 2011, by the Egyptian artist Ahmed Basiony (1978–2011). Three days later, he died of gunshot wounds, shot by the Egyptian police firing on the demonstrators in Tahrir Square. His words of encouragement to others resonated deeply, as we heard him inviting everyone to join the demonstrations, and reminding them not to abuse the police or the soldiers, for (he says) we regard every Egyptian as a human being, even if they do not. The next day at the railway station, I saw a videotaped lecture, The Pixelated Revolution (2012), by Rabih Mroué (b. 1967, Lebanon), where he discussed the documentation of deaths in the ongoing Syrian Revolution, where people inadvertently recorded their own shooting and indeed deaths on their cell phones. Fascinated by the search for the face of the sniper in the street, the person with the cell phone seems to forget he or she is visible, the actual target, a fact brutally registered when the soldier raises his gun and the phone falls to the ground. Mroué considered our relation to the screen: we feel invisible in the cinema, we do not feel seen, and what is the cell phone screen but a very small cinema? His address was straightforward, his curiosity and intelligence intensely present. Maybe it is the everyday ordinariness of cell phone photography that connects us so indelibly to those unknown people living and dying in Syria. Mroué discussed the abrupt trace of pure violence marked by the sudden end of the video recording. We don’t see the person filming, we see only what they see, a displacement that marks their end with absence, the nothing that comes after the phone is dropped. Like the void of Hoheisel’s anti-monument, and the real of Morandi’s oil lamp, the negation of the image allows space for reflection, and curiosity, and connection.

Ahmed Basiony, From day 2: a documentary video, January 26th, Cairo. Video stills. Courtesy the Estate of Ahmed Basiony.

In any case, connection prevailed, against logic, against all the odds, against the alienation of technology, the catastrophe of our shared environment, the divisions of war. Connection prevailed: across histories, in retreat, in subterranean passages, and echoing through indirect memorials and implicit rhymes. I was deeply glad that such a project could be realized, especially at this historical moment, where hope is elusive and memory so bleak.

Leslie Dick teaches in the Art Program at CalArts and is on the editorial board of X-TRA.