Whitney Museum of American Art

New York1

In “Entropy and the New Monuments” (1966), Robert Smithson writes about banal architecture, sci-fi movies and science displays, horror films, and the Second Law of Thermodynamics as a context for addressing the sculpture of various contemporaries, including Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, and Paul Thek. Invoking the architecture of sci-fi, he outlines the way these artists “provide a visible analog” for the phenomenon of entropy, and its paradoxical by-product, euphoria. On Thek, Smithson writes: “Thek achieves a putrid finesse, not unlike that disclosed in William S. Burroughs’s Nova Express: ‘Flesh juice in festering spines of terminal sewage… to the fish city of marble flesh grafts.’”2

Curators Elisabeth Sussman and Lynn Zelevansky have grappled with the ephemeral legacy of this influential and obscure American artist through a selection of Thek’s sculpture and painting, with photographic documentation of many years of restless performative installation work, of which little physical evidence survives. Thek is and was a challenging and fluid figure. In 1968, he made four latex casts of his naked body, arms over his head, his entire body girdled with cast latex fishes. Hanging overhead, Fishman positions the viewer deep under water, looking up at the body of a drowned man, supported or accompanied by fish. Distorted by time, Fishman barely survives. While the gaps and ruins of his work are daunting, it’s also true that Thek’s work always demanded intense imaginative engagement. In 2010, this is still the case.

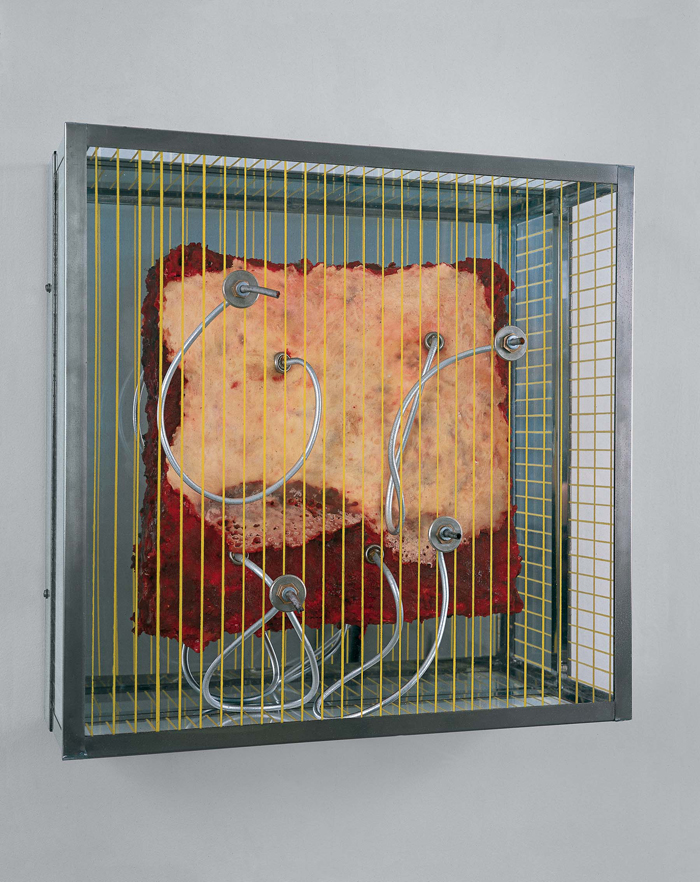

Paul Thek, Untitled (Four Tube Meat Piece), 1964, from the series technological reliquaries. Wax, metal, wood, paint, glass, plaster, rubber, resin, and glass; 16 1/8 x 16 1/4 x 5 3/8 in. Kolodny family collection. © The estate of George Paul Thek. Courtesy of Alexander and Bonin, New York. Photo: Orcutt & Van der Putten.

Untitled (1964) is a heavy slab of fatty, hairy, skinless flesh, almost square, with another almost square slab, smaller, lying on top of it–a meaty Josef Albers in a square glass box. The glass is painted with exact, narrow fluorescent green lines, a lattice between our living eye and this dead-or-alive Thing. Untitled (Four Tube Meat Piece) (1964) similarly presents a vertically oriented chunk of flesh, this time with four silver tubes connecting the surface of the meat to the glass front of the case. Is it a life support system? A communication device? Is the glass box a coffin? Or is it an incubator? Are we almost making contact with something from another planet?

Thek’s early meat pieces are contained in glass vitrines with shiny metal edges, similar to display cases in pastry shops.3 There’s horror in the exacting detail of Thek’s sculpture; the white fat laid over the very red flesh, the hair that protrudes from that fat, generate a bodily sensation that is far from comforting. In Meat Piece with Warhol Brillo Box (1965), the plywood Brillo Box is re-functioned as a container for a seething hunk of stringy, bloody flesh. He tips the box sideways, as if to expose its theatricality; the ghastly presence of the flesh inside presents that oozing, excessive body that Warhol never wanted to deal with directly. Thek was one of Warhol’s “13 Most Beautiful Boys.” Perhaps this is Thek’s revenge.4

Later, Thek used tinted Plexiglas to construct the vitrines. The seams of the boxes give off an intense fluorescent green, causing the case to appear to float. He said: “I do not know if the cases hold out the viewer or hold in the wax-flesh. Maybe it’s the same thing.”5 In a sense, the nameless Thing is being protected by the case, being sustained by it. On the other hand, its toxic, malevolent capabilities are being contained: the case is there to protect us. As we look at these meat pieces, our overlooked and forgotten bodies become tangible. With that sensation of embodiment, the repressed returns: sex and death, reminding us of our eventual and inevitable demise. The vitrine promises to hold that threat in, immobilizing the threat of the living body, as well as the threat of death itself.

The exhibition Paul Thek: Recent Work, at Pace Gallery, in 1966, took the meat pieces further, invoking a technological elsewhere that we access through the energy field of the strictly contained flesh. This group of meat pieces most deserves the title, retroactively assigned to them in the 1970s, of Technological Reliquaries. Within a vertical Plexiglas case is an inner case, a shiny metal column, presenting small transparent windows on four sides, revealing the skinless, gleaming red flesh inside. In Untitled (1966), the outer case is itself held within a pale pink melamine box, hinged and shaped to fit, implying a kind of transportation. The discrepancy between the size of the case (89 x 13 x 13 inches) and the relatively small display of the flesh (approximately 6 inches high) only intensifies its power. The double and triple encasement of the apparently living flesh emphasizes its preciousness and possibly also its vulnerability or danger, while pointing to the transparent protective containers found in nuclear reactors, or display cases in jewelry stores and museums.

Paul Thek, Warrior’s Arm, 1967, from the series technological reliquaries. Wax, paint, leather, metal, wood, resin, and plexiglas; 9 1/2 x 39 x 9 1/2 in. (24.1 x 99.1 x 24.1 cm). Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, the Henry L. Hillman Fund, Mr. and Mrs. James H. Rich Fund, Carnegie Mellon Art Gallery Fund, A.W. Mellon Acquisition Endowment Fund, and Tillie and Alexander C. Speyer Fund for Contemporary Art, 2010.3. © The estate of George Paul Thek. Courtesy of Alexander and Bonin, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

In 1966 and 1967, while the war in Vietnam escalated exponentially, Thek made a radical shift, choosing to represent specific human body parts in clear Plexiglas cases, detached from the torso and encased in classical armor.6Warrior’s Leg (1966-67) and Warrior’s Arm (1967) are very precise, realistic wax sculptures, presented in such a low-key way that the glimpse of raw flesh that occurs at the site of the dismemberment is all the more disruptive. While the straps and buckles recall an iconography of sadomasochism, Thek’s references to Rome, empire, decline and fall, and the futile repetition of war are understated. His reluctance to cite the deaths of American and Vietnamese soldiers is clear. Nevertheless, the work suggests that we can only perpetrate war when we choose to forget our own embodied reality.

Despite, and perhaps because of, this seriousness, it is illuminating to reflect on this work in the context of Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” (1964). There is something very camp about Thek’s meat pieces; they are elaborate, exaggerated, fantastic, somehow both distant and abject, cold and hot. See Sontag’s Note 26: “Camp is art that proposes itself seriously, but cannot be taken altogether seriously because it is ‘too much.'” Or Note 39: “Camp and tragedy are antitheses. There is seriousness in Camp (seriousness in the degree of the artist’s involvement) and, often, pathos. The excruciating is also one of the tonalities of Camp… But there is never, never tragedy.”7

Warrior’s Arm and Warrior’s Leg offer commentary on the war in Vietnam that is displaced, aestheticized and stylized, in part through the transfer to a visual language invoking ancient Rome. The lure to the spectator–that these armored parts are displays belonging to the British Museum or the Metropolitan Museum–is interrupted by the shock of torn flesh, a shock the viewer cannot anticipate. The experience is embarrassing, almost eliciting awkward laughter. This combination of elaborate artifice, theatricality of presentation, horror, and comedy is very camp, as is the absolute commitment the artist demonstrates in the intensely realized production of the illusion.

And then it all goes trippy. In Untitled (1966-67), the wax arm is not a sculpted arm, but a direct cast of Thek’s arm, complete with tiny wrinkles of the skin on the back of his hand, the hair on his arm. Yet it’s painted silver with pink stripes around it. Jewels are embedded in it. Rings appear on a finger. The clear Plexiglas vitrine is draped with a piece of fabric that looks like a rectangular scrap of soft pink crepe de chine. To this is sewn a blond wig, the long hair hanging down the side of the pedestal like an exaggerated fringe. The fabric, both seamed and torn, appears to be derived from an indeterminate and obsolete undergarment. Here, with its hilarious fringe, it discreetly covers the end of the vitrine where the arm is cut away from the body. When we peer underneath however, there is no torn flesh, but a series of painted, indented rings, as if this ever-so-real silver arm were detachable, and could be slotted into a body again, in some not too distant space or time. The gesture of the fabric, sort of covering part of the display case, is supremely camp; it’s excruciating, it’s brilliant, it’s ugly-beautiful, funny-horrible, and grandly abject all at once. It’s moldy, a la Jack Smith. It’s a revelation.

Peter Hujar, Thek Studio Shoot Thek Working on Tomb Effigy 8, 1967. Color slide. © 1987 the Peter Hujar Archive LLC; courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

In 1967, Thek reached the culmination of his Technological Reliquaries with The Tomb, shown at the Stable Gallery in New York. The work was destroyed in the early 1980s, so all accounts derive from photographs and recollections. From the outside, it was a stepped pyramidal structure with an narrow doorway, allowing one viewer at a time to enter, and read the note: “Welcome: You are in a replica of the tomb…”8 Inside, a telephone booth-like structure, made of tinted Plexiglas, isolated the viewer from the scene. Lying on the floor was a dead figure, undeniably Paul Thek’s double, wearing a double-breasted jacket and jeans, all of which were painted petal pink. His eyes were closed, his tongue protruded from his mouth. Two dirty cushions supported his head, and cups and a bowl on the floor resembled funeral offerings. Butterfly pattern painted discs rested on his cheeks, like the coins placed over the eyes of the dead. Most disconcertingly, the fingers of his right hand were torn off, leaving bloody stumps, and three of these fingers were placed in a little bag hanging on the wall by his head.

The Tomb, sometimes incorrectly referred to as “Death of a Hippie,” is a huge vitrine, preserving a body that is dead as a doornail, though the shiny stumps where his fingers used to be look fresh. Thek’s construction and presentation of a second self, ideal and immobilized, frozen in time, is uncanny. The viewer, isolated and contained by the Plexiglas, steps into a replica of a tomb, not unlike the Egyptian tomb at the Met, and is invited to peer into another time and place, thousands of years distant. But the corpse-like figure belongs to 1967, propelling the viewer into another space/ time, another position entirely, where preserved pink hippies are themselves museum displays. The figure is a god, maybe, waiting for his own resurrection. The god is very dead.

Thek’s own resurrection took the form of a radical break with this sort of artwork, as well as a departure from New York for Europe. In the great chaotic collaborative installations that he made from 1969 to 1985, some elements from the previous work were recycled, including the “dead hippie” (sometimes shown in his packing crate, wrapped in a blanket and surrounded by sprouting onions) and occasionally even the Brillo Box. These installation projects opened up for Thek after his first exhibition in Germany, at Galerie M.E. Thelen in Essen, in fall 1968. Here (so the story goes) much of the work arrived damaged, and instead of postponing the show, Thek opened with all the sculpture collected in a roped off section of the gallery. Working at night during the course of the exhibition, Thek repaired and enhanced each piece, adding taxidermic birds and photos of his naked body interacting with the sculptures, moving them gradually out of the restoration area onto individual, well-lit pedestals in the main space.9

The Essen show was called A Procession in Honor of Aesthetic Progress: Objects to Theoretically Wear, Carry, Pull or Wave. The objects included wooden chairs with their seats cut out in a circle, with leather harnesses and supports to enable someone to wear them comfortably on their shoulders so the top of the head would poke through the seat, a ceremonial headdress. The shoulder supports, vertical shafts with half circles at each end, were doubled, so the chairs could be worn upside down or right side up. Either way, the opposite possibility was always present. There was a set of glass vitrines that were to be worn over the head, supported by wooden half circles. Creeping around on the chairs and the “head boxes” (Thek’s term) were lumps of wax-flesh, working to fold in or overlay another set of ideas: the ordinary object (wooden chair), its extraordinary potential for activation (parade mask), and the body language of the meat pieces (life/death/horror/body).

Paul Thek, Untitled (Sedan Chair), 1968. Wood, wax, paint, metal, leather, glass, and plaster; 79 x 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 in. (200 x 100 x 100 cm). Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Ludwig donation. Image courtesy Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln. © The estate of George Paul Thek. Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York.

The largest piece, Untitled (Sedan Chair) (1968), presented a wooden chair raised on horizontal shafts, as if to be carried. A broken plate holding a hunk of Thek’s meat sat on the chair; a glass box placed above the chair contained a two-headed baby, hanging from springs with a leather belt around its waist, ready to bob and dance. A carnival procession is conjured in the viewer’s imagination, in which the flesh/chair is carried through the streets, while figures wearing chairs and glass boxes dance alongside. The question of what’s living and dead, moving and still, is central to this work; it’s a celebration of monstrosity, a procession re-functioned as neither funeral nor wedding, but both. The details of the sedan chair invoke a fantasy Rome. The stuffed birds are both dead and alive like the meat. Time and action have been incorporated into the static objects, bringing them to life even as they sit staring at us, waiting to begin.

From this point on, Thek consistently used ordinary, everyday objects and increasingly ephemeral materials such as newspaper and sand, as if to guarantee these experiential environments could not survive or be reproduced. In part, this was a reaction to the preciousness of the original meat pieces.10 Newspaper was placed on the floor, used to built a pyramid, or a cave. He was interested in the way newspapers produce random juxtapositions, especially if the pages are disordered by being removed from the body of the newspaper and unfolded. In A Document made by Paul Thek and Edwin Klein (1969), the two collaborators placed objects, photos, a copy of Time magazine, postcards, etc. on one double-page spread from the International Herald Tribune.11 These horizontal tableaux were photographed from above, and printed in a large-format artist’s book. A Document exploits the capacity of photography to contain other photographs, for objects and text to refer to other times and places. It’s like a Thek installation in the form of a book; the background news sheet does not change, as what’s on it is arranged and rearranged, marking the time and space of production, the action of placing, removing, and layering different elements.

Thek’s paintings on unfolded sheets of newspaper from 1969 and onwards are often very simple in their iconography: a man diving into a blue sea, a view of an island, blue sea, blue sky. Using pink and blue as his fundamental colors, Thek does what he can to play with gender cliches. (There’s a thesis to be written on his use of pink.)12 Within this simplicity, a complex layering takes place. Painted marks register a past action–Thek painting. The page itself recalls a pre-history to that action (acquiring the paper, reading it), as well as a pre-history to that (the writing, editing, and printing of the paper), and a pre-history again in the events recorded or predicted by the paper. Another future is promised, a future where the newsprint yellows, becoming friable: where the painting falls apart. In the clearest terms, Thek builds history into his painting, a whole set of implied actions, unfolding forwards and backwards in time.

Thek’s meat pieces speak of preservation: this un-living flesh has been set outside time. After 1968, Thek’s work consistently involves history, action, and time. In Venice, in 1980, Breughel’s ziggurat Tower of Babel is sculpted out of sand, seven feet tall, resting on rough planks, supported by oil drums to make a raft. It’s the Raft of the Medusa, Huck Finn’s raft, Noah’s ark. A large sail, made of newspaper, has a small electric fan aimed at it, and all this is afloat on a sea made of ridged waves carved in sand, scattered with lit candles. In Philadelphia, 1977, another Tower of Babel, this time quoting Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, shelters Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which contains a cave made out of newspaper, holding a bathtub filled with water, oars ready, transforming the tub into a boat. In 1984, Missiles and Bunnies presents a circular fence made of doors, reminiscent of Louise Bourgeois’s cells. Circular holes cut in the fence reveal the raft, the sail, and a dozen cardboard silver missiles, pointing up towards the sky. These works are poignant, evocative, elusive in their frame of reference, and today no one dares to reproduce them, fearing awkward failure.

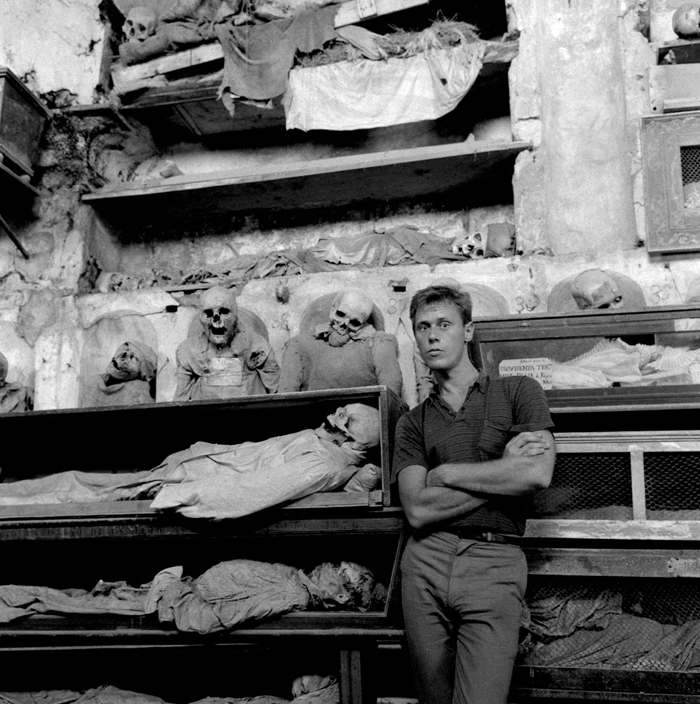

Peter Hujar, Thek in the Palermo Catacombs, 1963 (reproduced from the original negative, 2010). © 1987 the Peter Hujar Archive LLC. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

Paul Thek’s life story often takes the place of a deeper analysis of his artwork, as if the myth of the “dead hippie” supersedes all the other narratives. His last years were marked by poverty, isolation, and illness. Thek died of AIDS in New York in 1988 at the age of 54, a dead hippie indeed. While the story is very sad, and symbolizes something more than an individual tragedy, I want to resist a sequence that follows Thek from his notorious encounter with the catacombs in Palermo in 1963 to The Tomb in 1967 to his own dead end in 1988. Thek’s “putrid finesse,” his sense of Camp, his euphoria, his queer sexuality, and his celebration of the ephemeral as the stuff of life itself, open his work up to many different readings. All the museums apparently agree the large installations could not be reconstructed now. Why not? Are we so timid, so reverential, so historically accurate that we fear messing with Thek’s wonderful, multifarious messes? Maybe Thek’s commitment to incorporating time, action, and history into his work gives us permission to reactivate his utopian environments in our own time, or at least to make some of our own.

Leslie Dick is a writer who teaches in the Art Program at CalArts. She lives in Los Angeles.