While visiting Stockholm in the summer of 2006, I was struck by the sight of a large, inflatable bottle of ketchup visible through the leafy trees and the masts of the nice wooden boats docked around the little island that is the site of the Moderna Museet. Labeled “Daddies Tomato Ketchup,” the bottle was tethered to the top of the art museum and marked the location of Paul McCarthy’s 40-year retrospective, Head Shop/Shop Head: Works 1966-2006. Ketchup is one of McCarthy’s signature materials and when slathering it on his naked body in his early performances or spraying it all over the set of his 1991 video piece Bossy Burger, it becomes both a symbol of self-debasement and a form of cultural critique. In McCarthy’s hands, ketchup simultaneously suggests the great American family barbeque and fast-food franchise imperialism, as well as the history of bloody violence and exploitation on which the American empire stands. Daddies Ketchup Inflatable (2001) also refers to McCarthy’s preoccupation with the general paternalism of American culture that he sometimes represents through a controlling and violent father figure in his work.1 As the retrospective came to a close in Europe, a much smaller exhibition opened in San Francisco, curated by McCarthy himself to showcase the work of a variety of artists he has admired since his days as an art student in the 1960s. In the context of this exhibit, Paul McCarthy’s Low Life Slow Life: Part 1, the “Daddies” in McCarthy’s work become the teachers, mentors and influential artists occupying the pages of such journals as Artforum that helped shape his work as a young artist. And this San Francisco show indicates that perhaps McCarthy considers art history itself to be the biggest Daddy to be reckoned with at this stage of his career.

The site of this intriguing show is the gallery of an art school, the Wattis Institute at the California College of the Arts (CCA), and, as such, the perfect place for the artist to probe his relationship to the art of the recent past. McCarthy reveals this relationship to be complex and sophisticated and not the kind of tortured and rebellious struggle suggested by Daddies Ketchup. Though there may be fascinating connections to make between the images of Christmas trees used in the work of artists as disparate as John Heartfield, Wally Hedrick and Joseph Beuys, and we may delight in McCarthy’s rediscovery of the decaying work of assemblage sculptor Robert Mallary, one wonders who or what McCarthy is searching for and how we will know when he finds it. McCarthy’s interest in history, however, allows for an open-ended dialogue with the present that shows how much we are still working through the artistic discourses of the 1960s and demonstrates the extent to which the artist’s visceral practice was forged within the political crucible of that era. The fury and excess of McCarthy’s work is not on view here, but its roots can be seen in other artists’ approaches to unconventional materials and performative gestures.

Born in Salt Lake City in 1945, McCarthy attended the University of Utah between 1966-68 and the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) in 1968-69 before getting his MFA at the University of Southern California in 1973. The first part of this two-part exhibition addresses McCarthy’s student years and part two, slated for 2009, will cover the 1970s to the present. The logic of these exhibits is not a methodical presentation along the lines of “Paul McCarthy: In Context,” but rather a connect-the-dots approach governed by the artist’s memory of what was most important to him in those years. An immersive atmosphere is set by the early electronic music by Karlheinz Stockhausen playing throughout the galleries. The exhibition is a mix of artwork and museum vitrines containing McCarthy’s personal copies of Artforum, Life, the small-run art and poetry periodical Locations, a syllabus of one of McCarthy’s early art courses at Utah, and one of the artist’s most valued resources in this period, Allan Kaprow’s 1966 book, Assemblage, Environments & Happenings. These displays, and the binder for thumbing through photocopies of these materials, indicate the importance of print culture for the pre-Internet art world when the Western and Eastern U.S., let alone the globe, were far from the tightly integrated “information economy” of today.

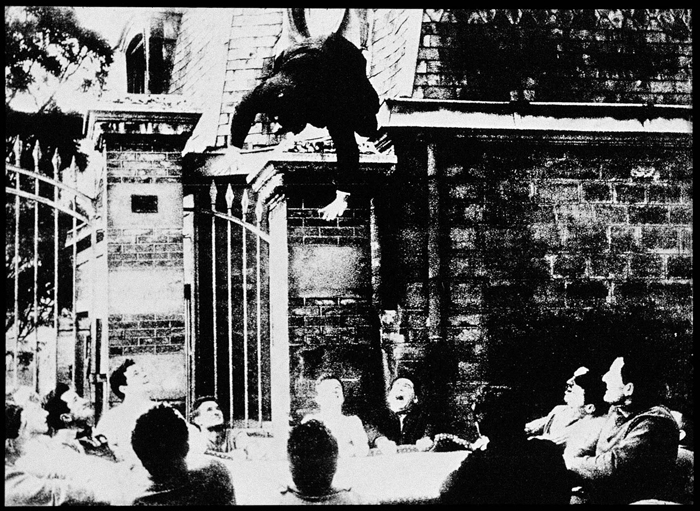

The press material for the show stresses recollection over influence as a guiding force for McCarthy’s selections, but one corner of the exhibit demonstrates the way these principles intersect. Along one wall there are a number of pages of the University of Utah student newspaper that announce a visit to the campus by Andy Warhol in 1966 and document the possibility that an imposter had posed as Warhol and taken off with the speaker’s fee. The adjacent wall presents another example of the manipulation of reality by a major postwar art figure, Yves Klein’s famous Leap into the Void (1960), a photograph reproduced in a mock newspaper broadsheet designed and printed by the artist. Both forms of publicity and self-promotion must have impressed themselves upon McCarthy, who built his initial notoriety upon confronting taboo subjects and making outrageous gestures. In fact, Klein’s leap so inspired McCarthy that upon first hearing about it as a student he jumped from a window in the university’s sculpture department in homage. Only later did McCarthy see the photomontage of the artist in full swan dive above the street and discover that Klein had removed from the image the people standing below him holding a blanket to catch his fall. McCarthy seems to revel in the fact that his repetition of this gesture not only turned out to be mistaken—he jumped feet first—but the “historical document” of this act was itself false.2 Reproductions of the two photographs Klein used to make this image accompany the broadsheet piece in the exhibit. In pairing the campus “Warhol” event with Klein’s work in this way, McCarthy brings personal and public history into contact by framing them through his own responses to these events. He also suggests that their duplicitous gestures “worked” to the extent that they revealed the need for their audiences, including the young Paul McCarthy, to believe in the idea of the visual artist as a provocative and magical individual.

Such archival material is not the only focus of the show. Some of the most compelling visual discoveries come from the juxtapositions of little known works that McCarthy brings together. Dominating the first room of the exhibit is Platform (2007), a new work by McCarthy that consists of a studio table piled with pails and containers, old Christmas trees and other detritus, all covered in layers of paint and glue. Surrounding this piece are several works that demonstrate McCarthy’s interest in strategies of accumulation and the notion of decay that always accompanies displays of excess. The Candy Shop (1978), a painting by University of Utah art professor Doyle Strong, faces McCarthy’s mountain of junk. Strong’s rather obvious symbolism of the abundant sweets and lollipops surrounds a jar stuffed with little American flags in front of a contemplative female shopper. The painting reminds us that McCarthy’s own use of the iconography of American pop culture often carries a political edge. In this light, the title for McCarthy’s 2007 work here, Platform, might not only identify the shape of the piece, but suggest that the word’s association with American party politics has something to tell us about the mess of materials on display in this work.

The counterpoint to these two dense, detailed pieces is the enormous, round, black monochrome painting by Wally Hedrick, Rondo/Rhondo, Iraq (1970-2003), hung high on the wall at the end of the first gallery. Hedrick never taught McCarthy at SFAI, but he was a major figure in the Bay Area whose influence has been underappreciated. Rondo/Rhondo, Iraq, is a painting that Hedrick reworked in response to the Iraq War. Initially made as an anti-war statement during Vietnam, Hedrick repainted the black canvas in 2003 after the invasion of Iraq, and the painting’s ominous presence dominates the first gallery of the exhibition. Hedrick’s most well known work, Peace (1953), is included in the next room. Over a simple representation of the American flag, not unlike the compositions of Jasper Johns’s more famous flag works begun a year later, Hedrick added the word “Peace” in reference to the Korean War, of which the artist was a veteran. This early Hedrick work anticipates the more angry, German Expressionist-inspired, protest-era paintings by McCarthy’s SFAI classmate Mike Henderson of the political and racist violence surrounding the student movement in 1968. With the inclusion of these two artists in this exhibition, McCarthy reveals the extent to which he remembers an art world on the West Coast that was deeply intertwined with politics—a fact that is often not recognized in art historical discourse about the period. While he makes legible this historical context in certain sections of the show, McCarthy’s reasoning behind other comparisons is not so easily grasped.

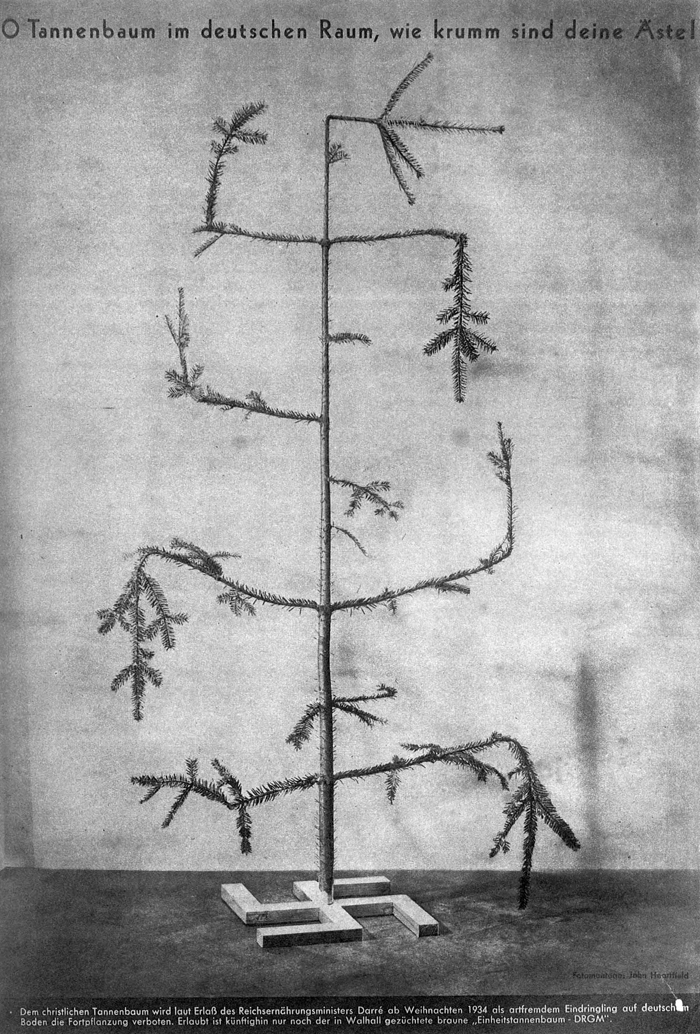

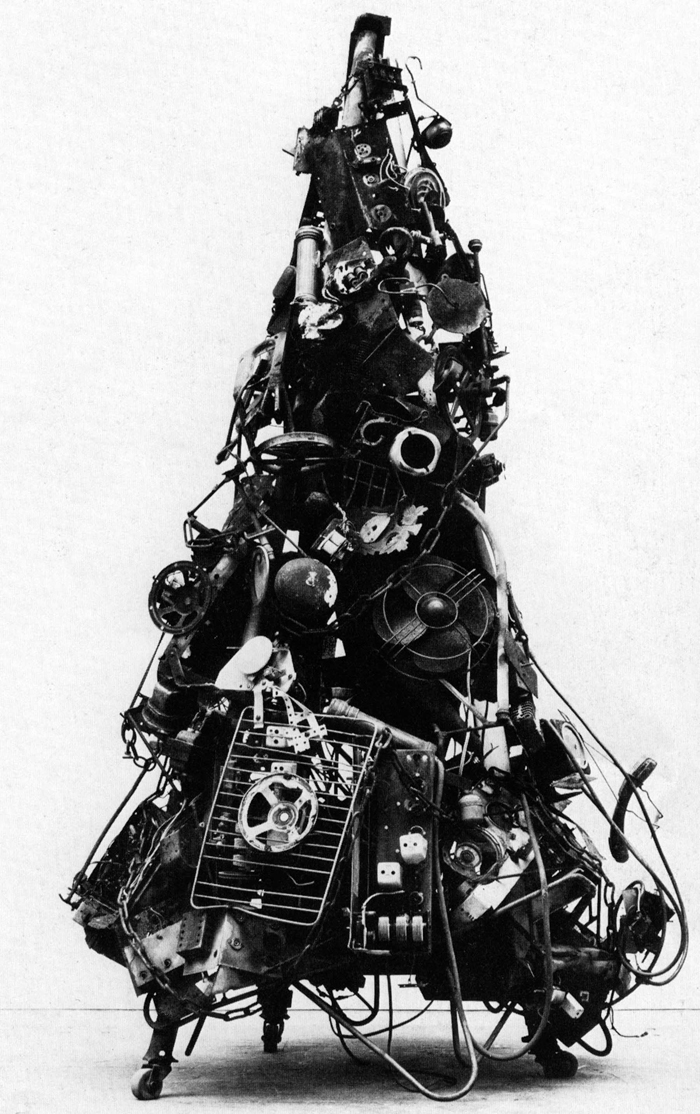

In a series of intriguing works installed as a group in the first gallery, McCarthy indulges in an iconographical thesis on the image of the Christmas tree in contemporary art. These include photographic reproductions of Joseph Beuys’ works The Needles of a Christmas Tree (1962) and Snowfall (1965), with felt blankets over fir branches; photographs by legendary Bay Area painter Jay DeFeo of her husband Wally Hedrick’s sculptures of Christmas trees nailed to plywood stands; and an image of a destroyed Hedrick piece, Christmas Tree (c. 1955), which consisted of a tree-like arrangement of discarded metal goods such as small fans and car stereo speakers. Along with two 2007 McCarthy sculptures using actual trees, Needles and Wally Beuys (which echo the ones “planted” in the muck of Platform), the whole collection is punctuated by Berlin Dadaist John Heartfield’s critique of the rise of National Socialism in his collage O Tannenbaum im deutschen Raum, wie krumm sind deine Ästel (Oh Christmas Tree in German Soil, How Bent Are Thy Branches) (1934). Oscillating between materiality, metaphor and overt political symbolism, these works leave the viewer to ponder the relationships between the artistic responses to the traumas of German history and the rise of consumerism and affluence in post-World War II America suggested by Hedrick’s assemblage of junked electronic parts and metal scrap. Additionally, McCarthy matches this political discourse with the more personal anguish depicted in a photo of Jay DeFeo’s studio after the extrication of her monumental painting The Rose in 1965. The image shows her having placed one of Hedrick’s scrawny, needle-less Christmas tree sculptures near the freshly cut hole in the wall used to crane the 2,000 pound painting to the street, a moment also hauntingly captured by Bruce Conner in his powerful film of the painting’s removal, The White Rose (1967).

Among many other major and lesser-known works on display are the drawings of Los Angeles painter John Altoon, a psychedelic-era installation piece by an artist astoundingly named “Adam (the late Paul Cotton) medium for Trans-Parent Teachers,” and videos by Bruce Nauman, Yayoi Kusama and Yoko Ono. In a film series accompanying the exhibit, McCarthy presented the films of Stan VanDerBeek, Stan Brakhage, and Bruce Conner. Two of the most significant inclusions in the show, to my mind, are the work of the East Coast assemblage sculptor Robert Mallary and a collection of paintings by McCarthy’s long-time friend, Al Payne. Though recognized as one of the pioneers of junk sculpture in the 1950s and early 1960s, Mallary did not have a New York gallery show between 1966 and 1993. The artist passed away in 1997 and McCarthy discovered some of Mallary’s most important early pieces rotting in his old studio in Massachusetts. McCarthy had planned to hang Little Hans (1962), a sculpture composed of a tuxedo, rope and polyester resin, from the ceiling of the exhibition space, but its fragile state forced McCarthy to install it lying on its packing crate on the floor. Displayed this way, it evokes a lifeless human body and its dusty surface resonates with the other work in the show suggestive of age and decay. Al Payne’s Painting Sheds (c. 1976-2005) function even more literally as a memorial to the artist since Payne died of cancer during the preparations for the Wattis exhibit. His death came as a surprise to McCarthy because Payne had not divulged his illness to anyone. Painting Sheds consists of a majority of Payne’s work locked away in two large, wood boxes displayed outside the Wattis space in the CCA’s entrance way. A video shown in the exhibition, separate from the work itself, documents the removal of these storage containers from Payne’s Bolinas property and their transportation on a flatbed truck to San Francisco for the show. Vaguely reminiscent of Robert Smithson’s Partially Buried Woodshed, the piece powerfully evokes the themes of presence and absence, tomb and monument, memory and experience.

The blank plywood walls of Painting Sheds, the lack of a window or any available documentation of what the paintings stacked inside these rough wooden buildings actually look like, suggests that this work stands for everything McCarthy cannot do by curating an exhibit of his past inside the galleries just beyond them. Painting Sheds represents a gap in history, a refusal of aesthetic experience that haunts McCarthy’s nuanced attempt to convey the texture of the historical moment that formed him as an art student. This nod to the failure of representation is remarkable for an artist whose seemingly endless and excessive deployment of highly symbolic content in his work leaves us to assume that it all must add up to something in the end.

Ken Allan is an assistant professor of Art History at Seattle University. His recent writing has appeared in Art Journal, Archives of American Art Journal, California History and X-TRA. He has contributed to Blanton Museum of Art: American Art since 1900 and is currently working on a book on art, spectatorship and social space in 1960s Los Angeles.