A photograph by Emma Kemp taken from the window of her father’s car on a trip to Dungeness, c. 2004.

This essay departs from a hole in the wall. I can try to tell you what I saw and what I could not see.

X—

1.

November. A pecan tree slams itself against my window as though it wants in. I’m thinking, this is the month of the hard, dry winds.

I log on, late. Join a meeting. Please wait, the meeting host will let you in soon. Soon takes some time and when I do make it in, the meeting is halfway through. This is life now. It isn’t how it used to be, but it’s not so different, either. My boss is saying something about retention; about how we need to engage students on Zoom. A colleague mentions that he has taken to setting his camera at a low angle and at an extreme distance, so that he can conduct class as a full-body performance. As he says this, I wince. And then I turn my camera off.

Last year I went home to England where I visited a favorite church. It’s called St. Clement’s, after Clement of Rome (35 AD), whose martyrdom transpired when he was tied to an anchor and thrown into the Black Sea. (The image of the anchor is one to which we will return.) Nestled three miles from the mouth of the English Channel in Kent, the church’s Saxon foundations date to the eighth century, with significant structural revisions occurring a few hundred years later under Norman rule, when William the Conqueror set about revitalizing Christianity in England.

I’m fond of St. Clement’s for at least three reasons. For one, filmmaker Derek Jarman is buried in the churchyard, his gravesite marked by a slab of dark slate, blank but for his signature—a small, neat sign-off. Secondly, the church has pink pews, a holdover from when the Disney Corporation filmed the smuggler tale Doctor Syn: The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh there in 1963. Most curious, though, most thrilling, are the thousand-year-old holes knocked in the wall.

They look like this: two large, arced apertures cut obliquely, at eye level, in the thick interior masonry on either side of the chancel arch. (The chancel is where the altar is located and where the priest performs the bulk of his work.) Probably constructed in the twelfth or thirteenth century when the building was in transition, these strange, askance perforations narrow as they recede. They are called hagioscopes, from the Greek hagios, a prefix applied to anything “sacred, holy, devoted to the gods,” and Skopos, an “object of attention.” The hagioscope, then, is a divine viewing device. Or more precisely, a device through which one comes to view the divine.

The interior of St. Clement’s Church, Romney Marsh, Kent, England. View showing the hagioscopes on either side of the chancel arch and pink pews opposite. Courtesy of theromneymarsh.net. Photo: Peter Faulkner.

This spiritual-spatial convention—colloquially known as a squint—began to appear in churches across northern Europe in the central medieval period, when sight and embodiment were understood as inextricably linked.1 We know this from a handful of medieval texts that specifically address visuality in relation to spirituality. Theologist and astronomer Peter of Limoges begins his widely circulated thirteenth-century treatise, De oculi morali (The Moral Treatise on the Eye), this way: “Thus, I am about to say a few words on the eye—since the fortifying of the soul is contained in them.”2 Peter’s exempla of the connectedness of sin, soul, and seeing are apportioned in categories such as “On Seven Distinctions of the Eyes According to the Distinction of the Seven Capital Vices” (Chapter 8) and “On the Four Things Spiritual Eyes Should Contemplate Continually” (Chapter 13). His priority, extending a lineage of medieval thought on the subject, was to convey how the physical appearance of the eye is changed by the moral character of that upon which it gazes.

Around the same time that Peter published his manuscript, the Catholic Church was busy revising its theological agenda, one outcome of which was the formal definition, and condemnation, of heterodoxy. Individuated voices were declared a form of heresy as the church sought to shift the locus of power away from the commons (the laity) and relocate it in the hands of the clergy, “most centrally in the Eucharist, which the priest controlled.”3 It is perhaps worth noting that prior to an especially vigorous Council of Laodicea meeting in the middle of the fourth century, the Sacrament was understood as a communal meal in which all partook, and the altar was typically located near the center of the church, so that congregants could gather around it. When the Council ruled that holy communion should instead be seen as a divine sacrifice to God initiated only by preapproved priests, it was decreed that no one but the priest was allowed to celebrate the Eucharist near the altar, and that women were not allowed to approach the altar at all.4 Much later, in 1215, a second reform movement prompted further stratification between the clergy and churchgoers.5 During this period, the altar slid—with what friction, who can tell—toward the eastern wing of the sanctuary, elevating the status of the priest as a more or less lone actor in the theater of the Mass, at the heart of which was the Eucharist and the concept of transubstantiation.

Video still from research footage by Emma Kemp of the hagioscopes in St. Clement’s Church, Romney Marsh, Kent, England, January 2019.

Church buildings were thus expanded to accommodate aisles on either side of the central nave, and hagioscopes installed so that congregants, newly distanced from the site of communion, could still view the moment of the elevation of the Host at the altar. It was a socio-spatial realignment made possible by a then-common assumption: seeing and being were equivalencies, two sides of the same coin. Embedded in this belief was an understanding of the body as a multivalent sensing organ; a wrinkled interface between experience and revelation whereby gazing, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting played a vital role in how one came to know God.

In fact, few institutions have been more concerned with the choreography of the body in space than the Catholic Church; an hourlong service boasts a dizzying assortment of gestures (kneeling, standing, bowing, dipping, shuffling, wailing) that coalesce into a series of ceremonial poses intended to bridge the terrestrial and the divine. The hagioscope, likewise, was the “paradoxical barrier” that connected distinct spaces of privilege.6 It was designed to keep the lay body at bay, offering instead a highly controlled ocular experience that was nevertheless understood as embodied.

X—

2.

Derek Jarman—himself canonized by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence—was someone who understood the meaning of divine and who frequently and joyously obliterated social orders.7 In 1987, seven years before he was interred in the grounds of St. Clement’s, Jarman made a home on a desolate stretch of pebble beach in Dungeness, just a few miles from the church. He named his home Prospect Cottage: an act of forward looking, to look upon that which is distant.8 After installing his desk beside a large window, Jarman set about planting a garden in the barren shingle. “He liked the impossibility of the task,” a writer inferred.9When Jarman’s unlikely bounty bloomed and blue delphinium burst through the shale, he rejoiced. “There are no walls or fences,” he logged in his journal. “My garden’s boundaries are the horizon.”10

Derek Jarman, The Garden, 1990. Frame grabs. S8mm and 16mm on 35mm, color, DolbySR SVA sound, 95 min. © Basilisk Communications. Courtesy of Basilisk Communications/Zeitgeist.

The horizon is the limit of the seeable, ergo what exists beyond is unseeable. “Eye-mark” (“eaggemearc”) is how the Saxons referred to it, the vanishing point out past the cold grey channel and the Strait of Dover and, perhaps, on a clear day, the wavering port of Calais.11 Looking ahead must have been troubling for Jarman, given that he had recently been diagnosed with HIV. His was a horizon in flux; convulsive, retractable, like the string of a bow. “I wish you were living with Aids,” he would come to pronounce. “But it’s the opposite, only dying, dying with Aids.”12 But what is dying is alive. Jarman’s relocation to the brink of England was a deliberate act of withdrawal (from the busy crowds of London) as much as a spirited act of rebellion (against the death at his heels, from which he would make life yet). He liked the impossibility of the task.

Backing up against a limit in the hopes of transcending it is a decidedly human maneuver. Such maneuvering was the primary business of anchorites and anchoresses, medieval laypeople who voluntarily ceded their bodies to Christ, withdrawing from secular society to exist in small, walled-in cells attached to a church. According to existing data, men were far less inclined to pursue this lifestyle than women; church records show that between the twelfth and thirteenth century, anchoresses outnumbered male anchorites by about four to one.13 When a prospective recluse was eventually admitted to the anchoritic life and led to her cell, a priest would recite “the office of the dead,” a set of funeral prayers symbolizing her departure from the world of the living. Once enclosed, the entrance to the cell was bricked up and the anchorite was legally bound in place, never again to leave.14 A life that begins with death sounds dreadful, but then again.

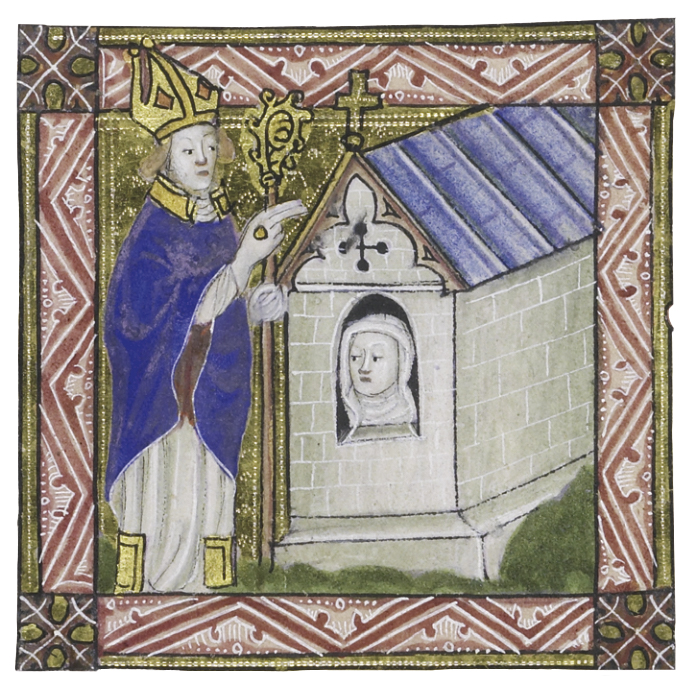

Depiction of a bishop blessing an anchoress in MS 79: Pontifical, c. 1400 and c. 1410. The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, MS 79: Pontifical, f. 96r.

Her cell eternal was called an anchorhold, existing somewhere between the worlds of the living and the dead and typically no larger than twelve feet square. It had three distinct openings, one of which was a hagioscope, positioned to offer an unencumbered view of the church altar. The second squint was designed to overlook a courtyard, or ideally, a garden. The third was a small opening through which a maidservant would deposit a daily meal and remove bodily waste.

Literature on the anchoritic life is scant, but a few preserved documents suggest that the anchoress subsisted on simple fare: “Potage made of herbs, peas, or beans, furmity sweetened with milk, butter, or oil, and fish seasoned with apples or herbs.” During Lent, she might have one meal daily, and on Fridays only bread and water. No flesh or lard was to be eaten “except in great sickness.” The hour of the meal was noon.15 Regarding “domestic matters,” anchoresses were advised to take “judicious care of the body: diet, washing, needful rest, avoidance of idleness and gloom.”16To avoid gloom seems to me the most difficult of the anchoresses’ charge. And yet one assumes this might very well have been the incentive behind her embrace of the reclusive life.17What then is the connection between enclosure (captivity, seclusion, solitude) and freedom from gloom? I think it has something to do with attention and the soul’s capacity for transcendence (as opposed to our contemporary method of distraction).18 At first this seems odd. And then perhaps it comes to make sense. Simone Weil, for example, had much to say about this kind of confounding religious attention, which was how she described her faith praxis—a slow, continual advancing toward the consent to be nothing.19To borrow a phrase from Hélène Cixous, we could reframe this as a quest “to make being say that it is not.”20

Depiction of an anchoress looking through the window of her cell at the altar in the church of St. Magnus in The Lives of the Saints Gallus, Magnus, Otmar and Wiborada in German, 1451–60. St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 602, p. 315.

Exactly why the anchoritic life so disproportionately appealed to women raises other, not unrelated, questions. Anne Carson, who locates solitude in language, would say that since antiquity and the establishment of patrilocal marriage, women have been considered “a mobile unit.”21 In contrast, the anchoress is a woman who chooses to stay in one place. The will of the anchor is stillness.

Julian of Norwich—an anchoress of the fourteenth century—was most offended by the “great busy-ness” outside of her window. She wrote vividly of “the Fiend [who] came again with his heat and with his stench, and gave me much ado, the stench was so vile and so painful, and also dreadful and travailous. And all this was to stir me to despair.”22 Notice the “heat” and “stench” of this fiend’s human flesh. Notice “despair.” Flesh without spirit simply stinks is a phrase scrawled in my notebook, a cobbled job from an afternoon with Susan Sontag’s journals. This stink was bothersome to Julian because it seemed to generate from a “bodily jangling” that she had long fought to contain. Eventually she arrived at a new plane of knowing: “Methought that busy-ness might not be likened to no bodily busy-ness.”

Depiction of a saint in front of the cell of an anchoress in The Lives of the Saints Gallus, Magnus, Otmar and Wiborada in German, 1451–60. St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 602, p. 303.

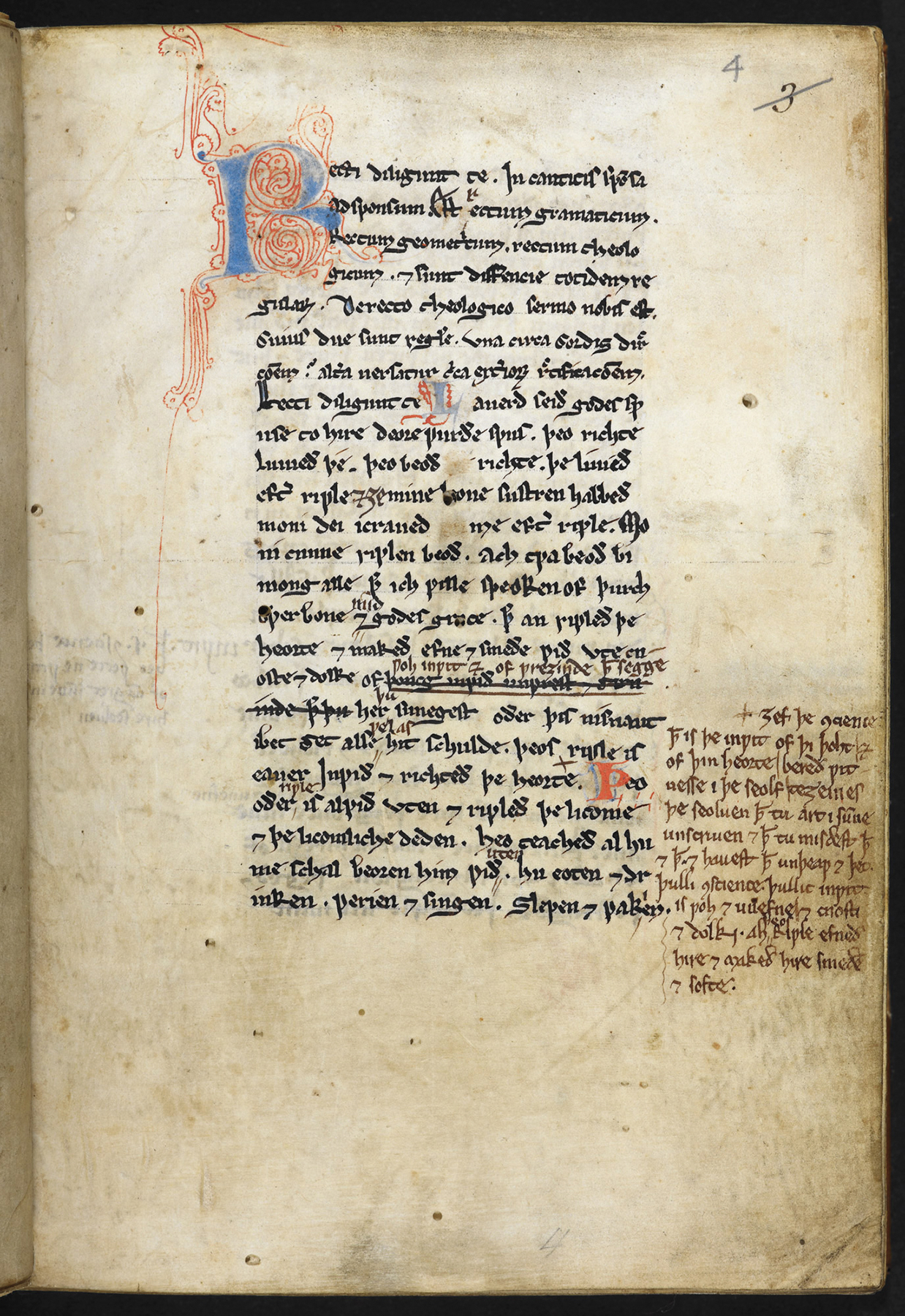

“That busy-ness” is faith business, distinct and separate from the “bodily” entanglements and idle chatter of the outside world. The outside was a continual source of strife for anchoresses, given that women, supposedly, were overly susceptible to the whims of erotic desire. A tradition of literature concerning the regulation of the female body qua female desire derives from this assumption. The Ancrene Wisse, a thirteenth-century spiritual treatise and also a handbook for anchoresses, is one such text. Strangely for its time, it was written in vernacular Old English rather than Latin or French, making it accessible to lay women as well as the religious elite, a kind of Marie Claire of the Middle Ages.

There are some parts of Ancrene Wisse that I like more than others. For example, I like the part that says an anchoress “should have no animal but one cat only.” Less appealing is the mandate that “Between meals let them [anchoresses] not snack (or, munch) on either fruit or anything else.”23 For the most part, though, its anonymous author—likely an Augustinian canon or a Dominican friar—seems anxious to protect his reader from the over stimulating outside. Particular instructions are given concerning the windows in her cell and the dangers of unrestrained seeing. “Hold no conversation with any man out of a church window,” he advises. Even when the recluse unclosed her shutter, she was to keep a curtain in place at all times—a black cloth bearing a symbolic white cross. “The black cloth also teacheth an emblem, doth less harm to the eyes, is thicker against the wind, more difficult to see through, and keeps its colour better against the wind and other things.”24

Clearly the curtain is necessary to shield the anchoress from her own desire, but there is reason to believe it held dual purpose: to protect free men from her dangerous gaze. Her flesh, he says, is a man pit, specifically her skin, her neck, “her roving eyes, her hand, if she holds it out where he can see it.”25 In an earlier anchoritic guide, a man writing for his recluse sister archived his fear in straightforward terms, insisting that if the window of a cell was widened to admit visitors, then the anchorhold would no doubt become a brothel.26

In her discussion of sight and embodiment in the Middle Ages, Suzannah Biernoff writes, “A desiring gaze foreshadows original sin.”27 She’s extrapolating from a note in the Ancrene Wisse: “The beginning and root of all this same sorrow was a careless look.”28 But what exactly does it mean to look carelessly? No wonder hagioscopes—which defined the parameters of one’s view—were popular: the stakes of an unruly eye were unbearably high, especially for women. The gaze in question, we note, belongs squarely to Eve. There are several examples, too, of the gendered, infectious gaze in Peter of Limoges’s Moral Treatise. In the eighth chapter, on vice, under the heading “How eyes of women have much unchasteness by which many [men] are wounded,” Peter explains how the eye can radiate and spread sin, referencing a “libidinous vapor” that emanates from the female heart, travels up through her body and corrupts her gaze, to infect “her visual rays.” When she looks upon a man who receives her gaze, he becomes infected as well.29

Peter’s description of women’s eyes as supercharged darts that “wound” supports his vivid analogy between female vision and the basilisk, a wicked bird-lion-snake hybrid, found in medieval bestiaries, that can kill by glance alone.30 Early descriptions of syphilis have been referred to as the “poison of the basilisk,” furthering the connection between lust, vision, and feminine contagion.31 Among other reasons to do with command of the visual field, this might explain why hagioscopes were often constructed to privilege one-way viewing. Anchorhold hagioscopes in particular favored this design, with a narrow opening on one side (the side closest to the anchoress) and a wider aperture on the other: a structural antidote to deleterious looking. I wonder how many anchoresses privately reversed this common logic and considered it, instead, a defense against the outside looking in? In one of my favorite sections of his manuscript, Peter presents a woman who was not afraid to challenge an authoritarian belief. The woman is a prostitute who has lost an eye due to disease. When confronted by a priest who tells her it was God’s vengeance for her sins, she replies, “I prefer to be content with one eye rather than with one man.” (Peter’s comment on this incident is that, while she may have lost one bodily eye, she has surely lost two from her mind.32>)

Ancrene Riwle (Ancrene Wisse); songs and prayers; a leaf from a Book of Hours, c. 1200. The British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra C VI. Public domain.

To keep the mind’s eye in service of God, it was suggested to anchoresses that they dig their own grave—little by little, day by day. The author of Ancrene Wisse phrases it this way: “[She should] scrape up the earth every day from the grave in which she will rot.”33 While digging, one is neither above ground nor below ground, but in between. The hagioscope is the medieval device exemplar of such in-betweenness and, accordingly, an anchoress was urged to use her liminal position, “betwixt and between,” to provide spiritual solace for her local community. When an anchoress died, she was usually buried there in her cell, which was subsequently bequeathed to a successor, establishing an unbroken tradition of prayer-in-place.34

If you’re anything like me, meditating on your own death is both humbling and traumatic. Once, at a workshop at Machine Project in Los Angeles, I was asked to sit in the dark and visualize my rotting corpse.35 A characteristic of de-composition is coming apart into pieces—a process of atomization that occurs each time we write.

X—

3.

In his last feature film, Blue (1993), Derek Jarman conveyed his own un-doing/un-being, but Blue is less a eulogy than a séance. “In the pandemonium of image, I present you with the universal blue. Blue, an open door to soul, an infinite possibility becoming tangible,” a voice narrates in empty blue space. Blue was important to Jarman, being the last hue to color his visual field. Speaking of his incredible loss: loss of friends, of sight, and of future, he says: “We all contemplated suicide.”36

Suicide, after all, is an unruly mode of escape, a way of walking backwards out the door. Jarman persisted and so did Cixous, who in the first few pages of her book Tomb(e) reports that, “In 1968/69, I wanted to die, that is to say, stop living, being killed, but it was blocked on all sides.”37Instead of suicide, she began to dream of building a tomb(e) for herself. Today, I pulled her book from my shelf and turned, instinctually, to the end. The first word in the glossary is:

ancre

Anchor

Homophone of encre: ink

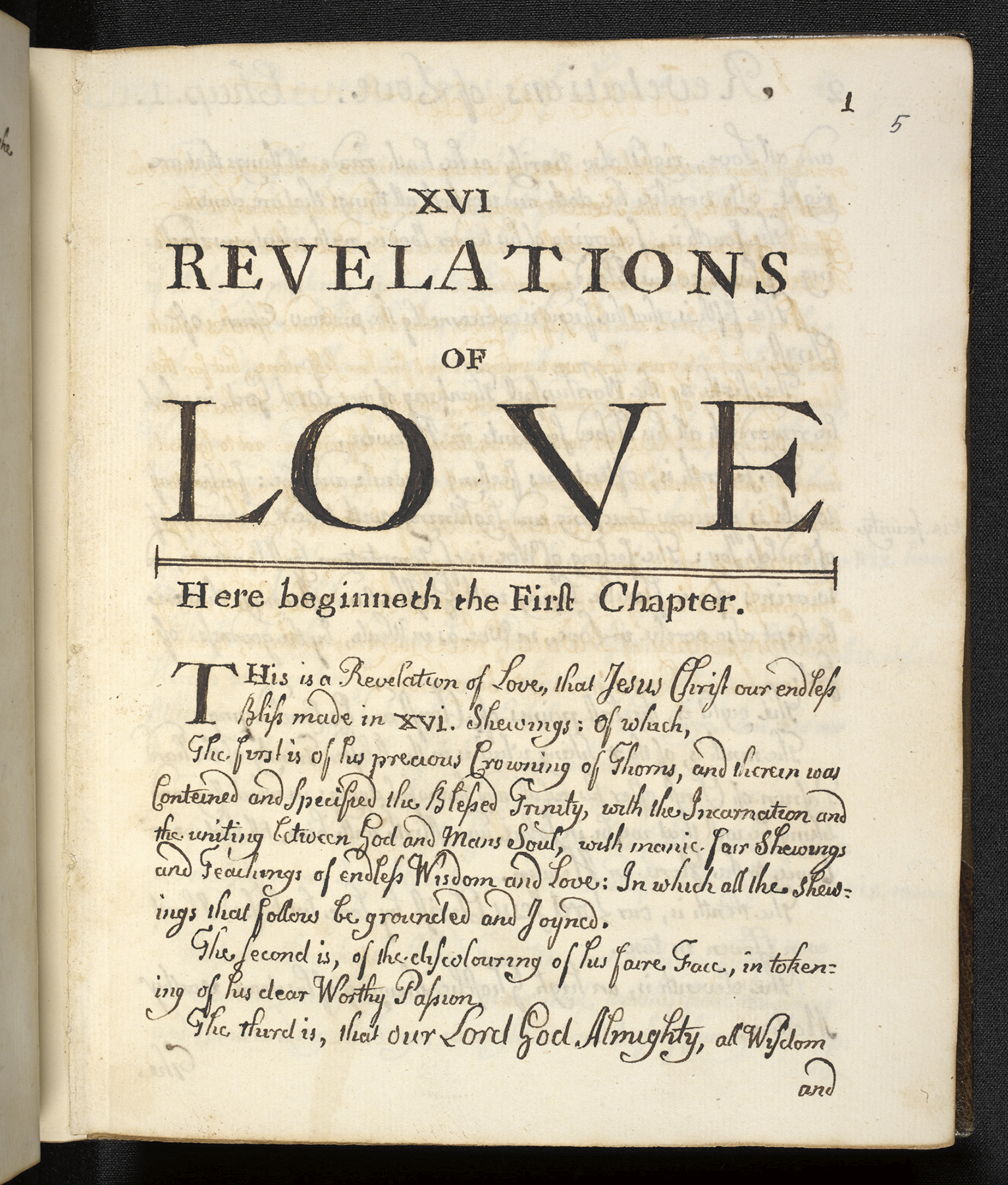

An anchor, like ink, fixes in place what floats, what is unmoored: boats, bodies, thoughts . . . Anchoring thought in ink is what we call writing. As it happens, anchoress Julian of Norwich was the first woman to write a book in English. She titled her prose Revelations of Divine Love. She recounts how, on the thirteenth of May, 1373, after seven days of sickness and in the throes of death, she received fifteen consecutive “shewings” from God. Divine Love is a window. Julian doesn’t tell us much about herself, but she describes her visions in detail, more or less inviting us into her cell to see for ourselves.

Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love to Mother Juliana, Anchorite of Norwich, c. 1675. The British Library, Stowe MS 42. Public domain.

In one profound section, she recreates her vision of Christ’s “deep dying.” (Note: not his death, his dying, which in Julian’s prose is both an adjective and a noun.) She writes, “I saw His sweet face as it were dry and bloodless with pale dying. And later, more pale, dead, languoring; and then turned more dead unto blue; and then more brown blue, as the flesh turned more deeply dead . . . This was a pitiful change to see, this deep dying. And also the [inward] moisture clotted and dried, to my sight, and the sweet body was brown and black, all turned out of fair, life-like colour of itself, unto dry dying.”38 This time last year, with the wind likewise howling, my boyfriend’s mother passed away. She had been dying for some time, and when we visited, she was only able to repeat the name of her life insurance company over and over again: a raspy, urgent prayer.

The financialization of death in the United States is extreme. It is not unusual, for instance, for families of deceased individuals to have to crowdsource funds in order to cover basic funerary expenses. But living, here, costs too. And while some can comfortably afford silent self-care retreats to soothe the soul, others are determined to equitably redistribute what’s left in the social fund. The heightened visibility of mutual aid networks, GoFundMe campaigns, and Venmo handles right now highlights the urgent role of the commons in providing support to individuals and communities, in the glaring absence of a social safety net.

In the case of the medieval anchoress, she too had to prove her worth. In fact, the process of becoming a recluse was surprisingly competitive. An interested candidate would have to apply to her local bishop with evidence that she was able to secure fiscal patronage from the village to support her lifelong enclosure. Something akin to a medieval credit check, or securing venture capital, or her friends donating dollars to her Cash App.

X—

4.

I am looking up the word anchorite in the dictionary while the Chair of Academic Assembly reads the minutes on Zoom. It comes to us from the Greek verb anacwre-ein, which means “to withdraw.” To withdraw, I am realizing, is not synonymous with dis-appearing. Neither does it correlate with non-participation. Women disappear all the time, not usually of their own volition. The medieval recluse, on the other hand, asserted herself as central to the commons precisely because of her seclusion.

Like the rest of us, I have been thinking about terms of communal engagement under pandemic conditions. Contrary to popular belief, the contemplation afforded by the anchorhold was not a solipsistic affair. By distancing herself to live an ascetic life, the anchoress served as a spiritual buttress to the community, the hagioscope her mediating portal to the outside world. I’m thinking that if Zoom is our twenty-first century equivalent, then we’d best figure out how to use it. Anchoresses practiced material devotion channeled through the notion of embodied sight: a strange, reciprocal seeing that was receptive and vulnerable (capable of transforming the observer) as well as active (able to “pierce” and influence the observed). To put it another way: seeing was a physical encounter in which one’s soul would extend towards an object, and vice versa. This premise takes on a sinister reality in our algorithmic age. Through the logics of communicative—or psychic—capitalism, what you look at actually dictates what you see, what is conjured before your eyes: a chain of toxic linkages between what one speaks, types, searches, and clicks and what appears in purchasable form.

The next time I glance up at the screen, I’m caught off guard: a data glitch projects my colleague in double, stuck beside herself in a sideways astral projection.

Now when I write I try to focus on my boyfriend’s mother’s ashes. She’s in a white cardboard box on the bookshelf, placed beside an antique wooden clock in an accidental vanitas. In Derek Jarman’s final years, he chose to look upon the desert-shingle shores of the English Channel, where blue fades into blue. In his book on color, he tells us that it was with lapis blue that the Venetians painted distance; it’s a color “that scream[s] at you from the horizon as skies once painted in harmony almost fall out of the frame.”39 I was maybe sixteen and screaming inside the first time I drove out to Dungeness in the passenger seat of my father’s Volkswagen. Beyond the window was a blur of yellow-blue; fields of bright crosses, canola flowers, reaching to a band of periwinkle; bright like flint sparking.

X—

Emma Kemp is a writer living in Los Angeles, where she teaches at Otis College of Art & Design.