Attention Line, installation view, Artists Space, New York, June 11–August 20, 2022. Courtesy of Artists Space. Photo: Filip Wolak.

A drag performer makes a movie spoof of a Woody Allen film spliced with a story about skinheads fighting to suppress their homoerotic desires. A self-professed alcoholic and diabetic Native American artist rides a stationary bicycle while Dean Martin’s “Return to Me” plays in the background. A resident of the Lower East Side collects littered bottle caps in hopes of one day converting them into a micro-economy for children and senior citizens.1

These acts of disruption, in which new meaning is made from the detritus of American social life, belong to three iconoclasts—Vaginal Davis, James Luna, and Rolando Politi—whose performative and participatory approaches to place and culture are included among the many works featured in Attention Line at Artists Space. Curated by Jay Sanders and Andrew Lampert with assistance from Stella Cilman, the exhibition surveys a sampling of US-based artists who challenge the structures of cultural hegemony using tactics that are vehemently anti-institutional.

Attention Line features a sprawling roster of artists and agitators—Blaster Al Ackerman, Craig Baldwin, Ed Bereal, Circus Amok and Jennifer Miller, Manuel DeLanda, Tom Murrin, Tamio Shiraishi, Hannah Weiner, and Johanna Went, in addition to Davis and Luna—and a robust schedule of public programming, for which Politi was brought in. The show frames these figures—many of whom are only now gaining recognition after decades of obscurity—as cultural irritants whose copious output has been classified as art because all other categories have proved insufficient.2 In doing so, the show positions them as thinker-organizers rooted in identity and class struggles and working to hone a sharper critical consciousness within revolutionary groups.

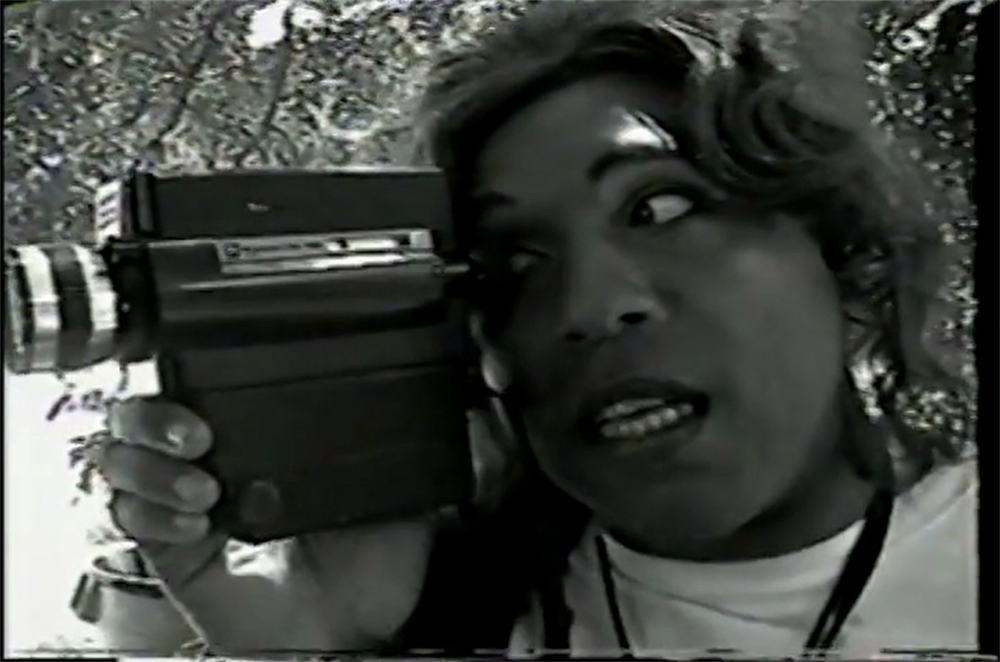

Vaginal Davis, The White to Be Angry, 1999. Film still. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.

On the one hand, the exhibition, whose stated goal is to present a brief history of “tactical situationist artmaking,” has its global touchpoints, including the Situationist International group in Europe, which operated from the late fifties to the early seventies and disbanded around the time the artists in Attention Line started to make work.3 On the other hand, the curators saw the artists’ tactics as distinctly “American,” owing to the ways in which they absorb and disidentify with US mass media.4 Among the works on display, Davis’s was the first to stand out as an exemplar of the “American” tactics as identified by Sanders and Lampert.

In Davis’s video The White to Be Angry (1999), which is screened behind a demure pink wall in the main gallery, white actors playing white supremacists gather in a living room festooned with Confederate and antisemitic paraphernalia, spouting tirades against miscegenation that betray a deep-seated conflation of disgust and desire. The main narrative follows a young skinhead grappling with his attraction to men of color. Meanwhile, Davis splices in a parody of Woody Allen’s film Interiors, a montage featuring a pair of serial killers, and shots of herself holding a camcorder and filming her friends. Characteristic of the artist’s style, The White to Be Angry gives the impression of having been improvised on a whim and edited in a blazing white heat.

Davis—sometimes Vaginal Creme Davis, sometimes Dr. Davis—came of age in the 1980s Los Angeles punk scene, in which youths banded together to skewer dominant American culture. She subsequently clashed with punk’s “whitewashing and heteronormative protocols” and again with the reactionary elements of gay culture that she encountered as part of the underground scene.5 In her drag performances, she appropriated and parodied these oppressive norms in a slapdash manner that, to this day, resists easy interpretation. According to Davis, “A lot of academics dismissed my work because . . . it was too homey, a little too country.”6

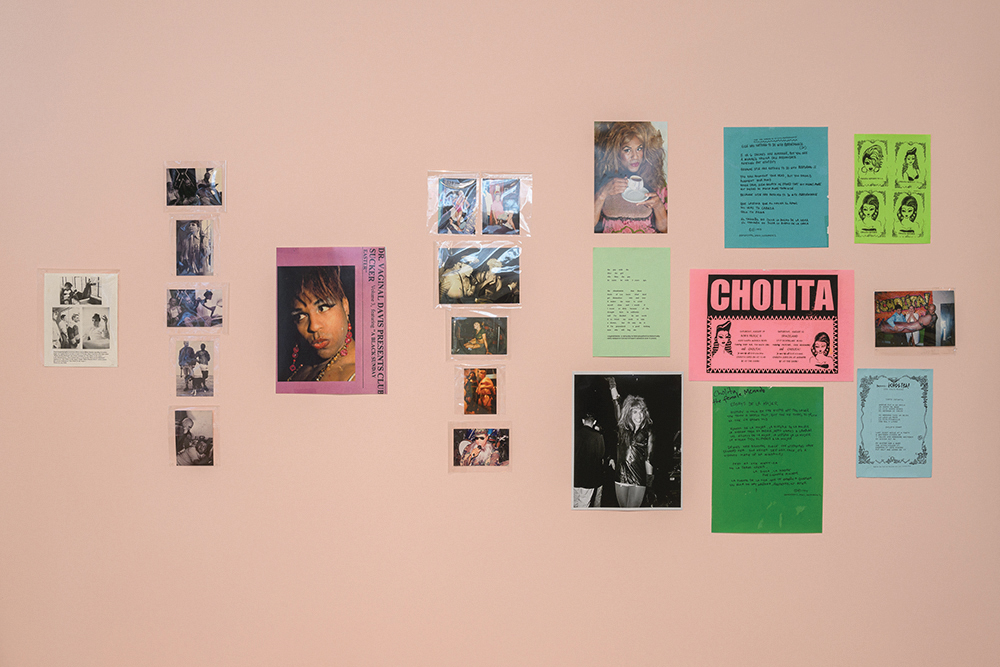

Attention Line, installation view, Artists Space, New York, June 11–August 20, 2022. Courtesy of Artists Space. Photo: Filip Wolak.

In 1997, José Esteban Muñoz published an essay on a performance by Davis and her band Pedro, Muriel, and Esther (PME) that later became The White to Be Angry. In that essay, Muñoz applied Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci’s idea of the organic intellectual to characterize Davis’s role in these subcultures.7 In Muñoz’s eyes, Davis presented herself and her work in a way that jettisoned polish in favor of guerrilla-style confrontations with dominant ideology. The author riffed on her words homey and country to arrive at an associated term— organic—which helped him connect Davis’s role as a thinker-organizer with Gramsci’s theory.8 According to Gramsci, an organic intellectual is one who has a “fundamental connection to social groups,” as opposed to one who ignores their relationship to class struggle.9

In the gallery across from The White to Be Angry is an altar-like monument to the late James Luna, who engaged in the same indispensable labor as Davis, although his work has a very different appearance. In My Dreams: A Surreal, Post-Indian, Subterranean Blues Experience (1996) is titled after Luna’s eponymous performance on the La Jolla Indian Reservation in 1996. In the original performance, which is looped on a small monitor in the corner of the gallery, Luna rides a stationary bicycle and wields an array of props associated with a predominantly white, commodified notion of Indigenous identity: a costume headdress, a dream catcher, a long spear. Meanwhile, he sips beer and smokes a cigarette. Projected on the wall behind him are clips from the movies The Wild One and Easy Rider, in which young white men on motorcycles seek out the freedom and catharsis of the American road. According to Jane Blocker, “The film [Easy Rider], released in 1969, had a strong impact on its young viewers but had a special significance for Luna and his college-age friends, for whom it resonated with the American Indian Movement and a validation of Indian identity.”10 Luna’s 1996 performance riffed on the toxic reciprocities between Indigenous and white cultures, as well as the generative connections between their countercultures. By taking control of knowledge production as it pertained to Indigenous experiences and turning the othering gaze of white hegemony on its head, he created sites where “history is remembered and memory is historicized.”11 In Attention Line, the artist himself, who passed away in 2018, becomes the subject of commemoration. His props, including his stationary bicycle, are combined with projections of The Wild One and Easy Rider (which are noticeably out of sync with the projection within the video). These elements are brought together around a void, as if waiting for the artist to return and activate them. The effect is disorienting and ironic, considering that one of Luna’s goals had been to subvert the stereotype of Indigenous people as a “vanishing race.”12

James Luna, In My Dreams: A Surreal, Post-Indian, Subterranean Blues Experience, 1996. Exercise bike, crutches, beaded shoes, video projection, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Artists Space, New York. Photo: Filip Wolak.

Luna and Davis are afforded ample wall space on which their ephemera is displayed, partly to provide context for those unfamiliar with their work and partly to ensoul the residue of their performances. This act of care is extended to all of the artists in the exhibition who could not appear in the flesh, whether for an artist talk or for an on-site performance. In some ways, their presence through artifacts mitigates the pangs of loss that puncture the gallery space, where past escapades are looped on grainy monitors. Nevertheless, one cannot help but sense that the costumes displayed on mannequins, the typed letters in vitrines, and the xeroxed flyers advertising performances that took place decades ago fail to sum up the imagination and intellectual labor that went into their production. The feeling of belatedness is at times enough to turn the gallery into a mausoleum.13

Attention Line, ephemera related to the work of Vaginal Davis, c. 1990s. Installation view, Artists Space, New York, June 11–August 20, 2022. Courtesy of Artists Space. Photo: Filip Wolak.

Where Artists Space did succeed in bringing this historically minded show into the present was in the accompanying public programming. For example, on June 28, 2022, the curators collaborated with Canal Street Research Association (CSRA) to host A Symposium on Alternative Currency in the basement of the gallery. CSRA, composed of artists Ming Lin and Alexandra Tatarsky, is known for facilitating conversations around the material culture of Canal Street and for collecting objects emblematic of the thoroughfare’s economic flows, such as t-shirts with misspellings of English phrases often hawked by Chinese vendors. According to Sanders, who has had a relationship with Lin and Tatarsky since the duo established their Lower Manhattan storefront in 2020, the pop-up research association is an “elaborate living theater, ad hoc community memory bank, and venue for serendipity.”14

During the symposium, which featured perspectives on the viability and complications of alternate currencies ranging from time banks to Spacebank, CSRA introduced visitors to Rolando Politi, a waste picker, homegrown theorist, and local historian.15 Politi spoke extemporaneously about his habit of picking up bottle caps, which, to him, represent a potential form of alternate currency. He uses the caps to decorate the surfaces of various receptacles along the streets in the Lower East Side with their eclectic hues and lusters. He also discussed the years he spent working in the Seemapuri neighborhood of Delhi, India, where he organized a co-op of women waste workers who made toys and decorative knickknacks out of the trash they gleaned.16

Attention Line, installation view, Artists Space, New York, June 11–August 20, 2022. Courtesy of Artists Space. Photo: Filip Wolak.

Politi’s long-term project, not unlike those of Davis and Luna, is concerned with self-awareness in communities. He draws our attention to the waste that accumulates on the streets and to the economic and near-economic transactions that generate it. He initiated his latest alternative currency project, Kap Kurrency (2022), as part of Attention Line. In this endeavor, the artist invites participants to pick up bottle caps from the street and deposit them in a sculpture made from a repurposed five-gallon water cooler, which he has affectionately titled CROSS EYED CHARLIE / THE CAPS GOGGLER / FREE YOUR CAPS HERE (2022).

Politi’s description of Kap Kurrency was as thought-provoking and enriching as it was associative and meandering. It soon became clear that his project was propelled by disgust and desire—and a commitment to ambulatory drift. In the Situationist International Anthology, Ken Knabb defines drift, or dérive, as “a mode of experimental behavior linked to the conditions of urban society: a technique of transient passage through varied ambiences.”17 In this way, Politi’s project overlaps with that of CSRA, which is to make Canal Street—with its human flows, its ecological history, its circulation of objects both “legitimate” and counterfeit—into a coherent entity of study while also pointing out the site’s incoherencies, its internal contradictions, its resistance to interpretation.

Most importantly, Politi’s participatory project creates an imagined community of homegrown currency users. At the symposium, the compassionate ingenuity of Kap Kurrency made other alternate currencies, such as the time banks of Cascadia and the BerkShares of Massachusetts, appear bureaucratic and artificial.18 I found myself rooting for Politi’s homegrown methods, despite knowing that his bottle caps have never formally circulated.

Echoing the complaints of the Situationist International, which claimed that lived experience had been transformed into spectacle and desire into consumption, the works in Attention Line demand, from within the space that frames them as art, social revolution that surpasses art. Inevitably, such a show turns its critique back on itself, most notably by revealing, in the juxtaposition of past action and present commemoration, the tendency of such historical surveys to defang and petrify the revolutionary impulses they aim to highlight.

Rolando Politi, CROSS EYED CHARLIE / THE CAPS GOGGLER / FREE YOUR CAPS HERE, 2022. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Artists Space, New York.

While visitors are given the opportunity to revisit the contributions of these cultural disruptors and to participate in a socially engaged mode of knowledge production, it becomes apparent that there is no easy way to pick up where these organic intellectuals of the seventies, eighties, and nineties left off. That much was evident even at the time when the costumes were worn, the posters were wheat pasted, and the tactics were dreamed up.

This gap, I would argue, is precisely the point.

Jenny Wu is a fiction writer, art historian, critic, and curator. She has organized exhibitions of contemporary art in St. Louis and New York, and her writing has been featured in BOMB, Brooklyn Rail, Los Angeles Review of Books, Millions, and Ploughshares.