On Christmas Day in 1968, ten months before Mierle Laderman Ukeles sat down to write her Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! Proposal for an Exhibition “Care,” Apollo 8’s manned space mission sent back to NASA paradigm-altering images of Earth. In one of those photographs, Earthrise, our shadow-cloaked planet looms in darkness beyond the desolate lunar horizon. “It was the most beautiful, heart-catching sight of my life, one that sent a torrent of sheer homesickness surging through me,” expressed astronaut Frank Borman. He followed up his emotional statement with a more philosophical observation: “[R]aging nationalistic interests, famines, wars, pestilences don’t show from that distance. We are one hunk of ground, water, air, clouds, floating around in space. From out there it really is ‘one world.’”1 When confronted with a view of Earth as a single, contained sphere rotating in space, Borman’s pronouncement oscillates between the hyper local and the global, between emotion and practicality. The breadth and scope of this “one world” deliberation also resonates with Ukeles’s comprehension of what she calls art’s “Real Job”: “that which saves the planet/home.”2 In 2016, she described writing her Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! in a state of “quiet rage, in one sitting… From the beginning, I name three levels of Maintenance as Art: Personal; Society/the City; the Planet. With limited resources from our finite planet, how do we do this? How do we survive?”3

Earthrise was not the first photograph of the entire planet recorded from space. A colored image captured by NASA’s satellite ATS-3 (in 1967) appeared on the cover of the first Whole Earth Catalog, in fall 1968. However, Earthrise was the first to be generated within the technological feat of a manned space mission and therefore the first to appear with a commentary from participant observers. Earthrise, together with The Blue Marble (1972), sent to earth from the Apollo 17 mission, unmistakably captured the imagination of environmental activism, a movement that peaked between 1968 and 1972.4 The organizers of the historic 1972 United Nations Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment asserted that The Blue Marble “had initiated a shift in human consciousness akin to the Copernican revolution” and claimed that the image itself had “brought about a comprehensive change in consciousness and promoted new notions of a planetary unit and the ‘earth system.’”5

The Blue Marble, 1972. View of the Earth as seen by the Apollo 17 crew traveling toward the moon. Astronaut ATSphotograph AS17-148-22727, http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov . Courtesy of the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, NASA Johnson Space Center.

In preparation for the United Nations conference, the UN General Assembly commissioned economist Barbara Ward and scientist René Dubos to co-author a report that resulted in the lauded publication Only One Earth: The Care and Maintenance of a Small Planet.6 In the book, Ward argues for the “dual responsibility” of caring for the environment’s “outer limits” as well as the “inner limits” of humankind. Ward states, “[T]he careful husbandry of the Earth is sine qua non for the survival of the human species, and for the creation of decent ways of life for all the people of the world.”7 For Ward and Ukeles alike, it was simple; an attentive practice of “care and maintenance,” on both a personal and global level, was the means to surviving on a finite planet with limited resources.

Ukeles’s early maintenance performances included housecleaning, washing dirty diapers, and dressing children. By framing domestic tasks as art making, she transformed the routine of private labor into a question of social responsibility and public work. As artworks these maintenance activities can also be understood symbolically, as an act that reaches far beyond the broom closet. The same sort of diligent “maintenance” applied to the household can also be a metaphor for civic-minded work. And responsible civic work is always environmental and global. Ukeles’s engagement with maintenance and care may have originated in the home, but its ethical scope is not confined to the contours of the domestic institution. “Think Globally, Act Locally,” another remnant of the 1972 Stockholm conference, is an axiom that is deeply embedded in Ukeles’s practice, and the NASA photographs made this concept visually conceivable to the world’s inhabitants.

Also in 1972, the Queens Museum opened in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. Its enduring feature attraction is the Panorama of the City of New York, an accurate 1:1200 (one inch = 100 feet) scale model of the city’s five boroughs, constructed for the 1964 World’s Fair.8 Today, visitors to the museum can navigate above the perimeter of the large-scale model and enjoy a topographical god’s-eye view detailing 320 continuous square miles of water and densely urbanized landscape. This replica offers human proximity that is distinct from the radically incomprehensible distances that frame NASA’s Whole Earth images. But the New York panorama also assumes an aerial perspective that effectively mediates between the individual and the local in ways that parallel the mediation between the individual and the universe.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Ten Sweeps Light Path, 2016. Installation view, Queens Museum, September 18, 2016–February 19, 2017. © 2017 Queens Museum. All rights reserved. Photo: Hai Zhang.

The Queens Museum’s Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art is a major survey exhibition that features work from 1962 to 2016, much of which coincides with Ukeles’s nearly 40-year unsalaried tenure as the official artist-in-residence of New York City’s Department of Sanitation. A powerful inclusion in the document-heavy exhibition is Ten Sweeps Light Path (2016). Using a path of flickering lights, the piece maps, onto the museum’s Panorama of the City of New York, Ukeles’s routes through New York’s boroughs, as she performed Touch Sanitation Performance (1979–80). This project, in which the artist shook the hands of 8,500 city sanitation workers, was an immense yet intimate action that acknowledges an integral metropolitan workforce. Propitiously, the lights that flash along the streets of the miniature city reinforce a statement that Ukeles made to artist Linda Montano about the performance: “I felt I had absorbed eighty-five hundred volts of electricity through my right hand from shaking that many hands, and the energy was residing inside of me.”9 Trax for Trux and Barges (1984) is a two-part soundtrack that fills the museum’s panorama hall. Produced by sound designer Stephen Erickson and Ukeles, the racket of utility trucks and other heavy equipment dumping trash is interspersed with recorded conversations between Ukeles and “sani” workers inside the cabs of garbage trucks during Touch Sanitation Performance.

Social Mirror (1983) opens up a playful rupture within an exhibition dedicated to the ethical ramifications of work and routine. This garbage truck with mirror-cladded sides pulls up to the museum’s entrance on weekends during the run of the exhibition. The juxtaposition of a truck reflecting the classical architecture of the museum upends the illusion that timeless cultural institutions produce no waste and need no maintenance. Equally advantageous, the location of the parked truck perfectly aligns with the Unisphere, the iconic stainless steel representation of the Earth in nearby Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. Its diameter measures 120 feet, and it was erected as a symbol of global interdependence in 1964, at the beginning of the space age. This fortuitous juxtaposition of a garbage truck and the Unisphere draws a direct relationship between regional management and planetary guardianship. Reflected on the broad sides of the rear-loader, the image of this globe does not float in the vastness of space but instead is tethered to a maintenance vehicle.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Social Mirror, 1983. Installation view, Queens Museum, September 12, 2016– February 19, 2017. © 2017 Queens Museum. All rights reserved. Photo: Hai Zhang.

Seemingly in contrast with the monumentality of a rigged garbage truck, the four typewritten pages of onion-skin paper that make up Ukeles’s Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! are of equal force and momentum, and not solely for the work’s influence on women’s rights, cultural work, and labor. “This is a structure that is actually a sculpture though it looks like a text,” writes Ukeles in 2015.10 Understanding her manifesto as possessing the same authority as sculpture parallels her full endorsement of maintenance activities as art. Moreover, the manifesto is also a serious and well-crafted exhibition proposal. Comprised of two sections: “I. IDEAS” and “II. THE MAINTENANCE ART EXHIBITION,” Ukeles’s language is declarative, blunt, and on occasion discursive. Under “IDEAS,” she writes: “Maintenance is a drag, it takes all the fucking time (lit.).” She follows with “Everything I say is Art is Art. Everything I do is Art is Art.”11 Here Ukeles equates art with the repetitious nature of labor simply by emphatically claiming Art twice in each sentence. Ukeles thus registers philosophical and pragmatic views on maintenance and human development, life and death, art and the avant-garde.

In “Section II. THE MAINTENANCE ART EXHIBITION,” Ukeles manifests her thesis into a well-reasoned exhibition proposal for an art institution, presumably one with cultural clout. Her pitch is organized around three themes—Personal, General, and Earth Maintenance. She starts “A. Personal Part” by introducing herself as an artist, woman, wife, and mother (in what she describes as “random order”) who does “a hell of a lot of washing, cleaning, cooking, renewing, supporting, preserving, etc. Also, (up to now separately) I ‘do’ Art. …Now, I will simply do these maintenance everyday things, and flush them up to consciousness, exhibit them, as Art. …I will sweep and wax the floors, dust everything, wash the walls (i.e. ‘floor paintings, dust works, soap-sculpture, wall-paintings’)… The exhibition area might look ‘empty’ of art, but it will be maintained in full public view. My working will be the work.”12

Under the “B. General Part” heading, Ukeles details her plans to interview exhibition spectators, asking questions such as “what is the difference between maintenance and freedom; …what is the difference between maintenance and life’s dreams.” In addition, she states that the exhibition will also include printed interviews with the “‘maintenance man,’ maid, sanitation man, mailman, union man, construction worker, librarian, grocerystore man, nurse, doctor, teacher, museum director, salesman, baseball player, child, criminal, bank president, mayor, movie star, artist, etc.” Finally, the last part of her proposal, “C. Earth Maintenance,” describes the daily delivery of refuse to the museum, including the contents of one sanitation truck, containers of polluted air and water, and some “ravaged land.” These containers would be “serviced” by the artist or “scientists”: their contents “purified, de-polluted, rehabilitated, recycled, and conserved.”13

An exemplary work of feminist art making, Ukeles’s manifesto is an ambitious and bold declaration of subject and intent. Perhaps even more than the temerity of maintenance art is the manifesto’s pragmatic clarity as a spot-on pitch directed at enticing institutional authorities. Ukeles decided early on that for maintenance to be framed as art she would need to practice its routines within the hallowed walls of the museum. Or on its front steps. At the Wadsworth Atheneum in 1973, she performed Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside (July 22, 1973), mopping the exterior of the museum and the inner Avery Court. The photographic documents of that work have become the visual emblems of Ukeles’s manifesto. A black-and-white image of the artist on her knees dumping soapy water from a mop bucket down the steps of the gothic revival building, in which Ukeles’s sturdy frame cradles the discharge of liquid, evokes archetypal Madonna with Child imagery. With purpose and youthful comportment (and wet jeans), she looks down at her work with a sense of responsibility. The photograph’s triangular figural composition is solid and unyielding. From the photographer’s point of view, we see the figure situated above the public plaza, lending the subject a status of importance that effectively elevates both the quality of work and its endless nature. This photograph graces the cover of the Queens Museum exhibition catalog and has become synonymous with her oeuvre.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside, July 23, 1973. Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts.

Other photographic records of maintenance work include Ukeles’s earlier Dressing to Go Out / Undressing to Go In (1973). Here, a grid of 95 small photographic prints narrates the domestic routine of dressing and undressing young children. Hats, scarfs, boots, and snow coats cover and uncover little bodies who are knowingly aware of the camera in the room. Mounted at pre-school height, the camera cuts off Ukeles’s adult body while perfectly framing the action of dressing and undressing the kids. With no indication in the photographic series of an outdoor event, Ukeles emphasizes of the physical and temporal nature of the quotidian in ways similar to the multiple photographic frames employed by Muybridge to study anatomical locomotion. The work commemorates the process of dressing and undressing children in a daily routine shaped by seasonal conditions and champions the representation of repetitive care.

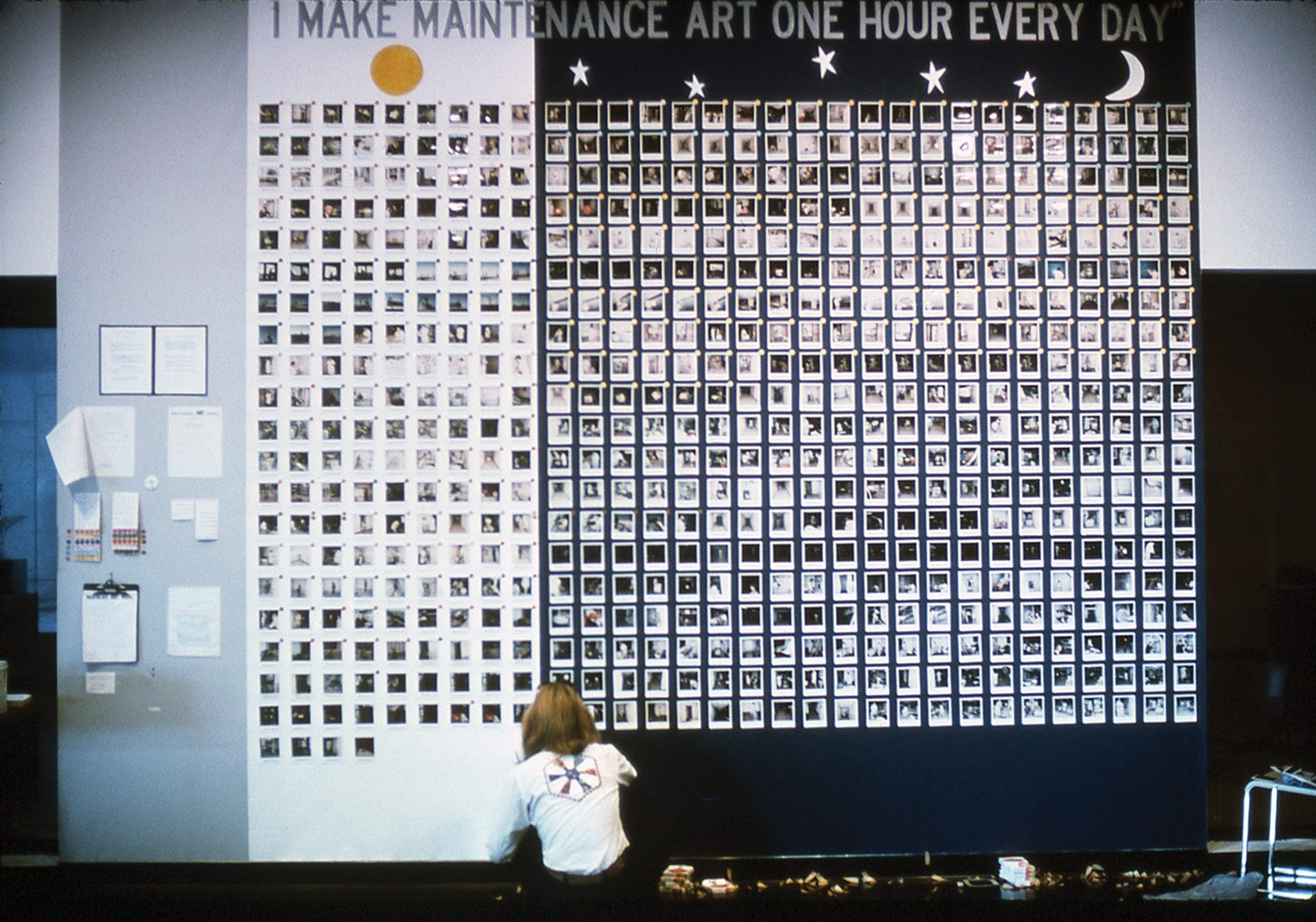

I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day (September 16–October 20, 1976) was a collaboration with 300 maintenance employees at the enormous office building at 55 Water Street, which housed the downtown annex of the Whitney Museum of Art. With the approval of supervisors, Ukeles asked shift workers to consider allocating one of their eight hours of work as “maintenance art” instead of “maintenance work.” It was a thought experiment that did not change the nature of the work, only the cultural framing of it. She took Polaroid photographs of the individual employees and gave each a white button printed with blue sanserif text, “I make maintenance art one hour a day.” In the Whitney Museum’s downtown gallery, she displayed the resulting 720 Polaroids as if on a bulletin board. She mounted the photographs on white paper if the employees worked during the day and on midnight blue paper if they worked the night shift (two thirds of the photographs are mounted on midnight blue) and hung them in a grid that constitutes an immense index of otherwise invisible human industry. Ukeles decorated the populous snapshot display with paper cutouts of the sun, moon, and stars. In a comprehensive and perceptive catalog essay, Patricia Phillips observes that this project “informed and inspired the process, planning, and deployment of Touch Sanitation Performance.”14

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day, September 16–October 20, 1976. Performance with three hundred maintenance employees, day and night shifts over the course of six weeks at 55 Water Street, New York. Installation view at Whitney Museum, Downtown NYC. 720 Polaroid photographs mounted on paper, printed labels, color-coded stickers, seven handwritten and typewritten texts, clipboard, and custom-made buttons, overall: 12 × 15 ft. Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts.

In the letter introducing Department of Sanitation workers to the Touch Sanitation Performance project, Ukeles wrote empathetically, “It’s about holding up your end of the truck team; about people swearing at you, not looking you in the eye; about doing a good job anyway.”15 “Thank you san-man. Thank you for keeping New York City alive!” Starting on July 24, 1979, as a newly installed artist-in-residence in the Department of Sanitation, Ukeles sent daily greetings via telex from the Department of Sanitation’s headquarters to the department’s entire workforce. In these messages, Ukeles informed sanitation workers in which district she would be working that day. Over the course of 11 months, the work she performed was to shake hands with the department’s 8,500 workers. She looked each one in the eye and thanked him or her.16 In addition to being an extension of maintenance and occupational art, Touch Sanitation Performance was a feat of durational art.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Touch Sanitation Performance, 1979–1980. Citywide performance with 8,500 Sanitation workers across all fifty-nine New York City Sanitation districts. Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts. Photo: Marcia Bricker.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Touch Sanitation Performance, 1979–1980. Citywide performance with 8,500 Sanitation workers across all fifty-nine New York City Sanitation districts. Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts. Photo: Marcia Bricker.

Ukeles’s project was informed by her predecessors’ practices, including Vito Acconci’s conceptualism, Hans Haacke’s political practices, Adrian Piper’s Catalysis performances, and Lucy Lippard’s feminism. For example, Acconci followed people around the streets of New York for 23 days. “Every day I pick out a person in the street—at random, any location—and follow that person as long as I can (until he/she enters a private place—home, office, etc.).”17 Photographic documents and notes, including accounts of Acconci’s daily episodes, comprise Following Piece (1969). Ukeles’s extensive and rigorous research, coordination, and administration in preparation for Touch Sanitation Performance is herculean by comparison to Acconci’s cache of artifacts. Lucy Lippard describes Ukeles’s project: “The spatial organization [of the 59 sanitation districts]…was organized by rhythm, intonation, and cadences of mobility (people, equipment, vehicles) and fixed forms and infrastructure (marine transfer stations, incinerators, landfills).”18 As a tool for recording and managing the personal time and labor necessary to execute Touch Sanitation Performance, Ukeles developed diagrams with notations inquiring about the availability of babysitters, her husband’s work calendar, and her children’s schedules. Yet her dogged persistence foregrounding the real forms of labor necessary to sustain the household, the neighborhood, the metropolis, and the world reached numerous people in their own workplace. Thus the municipal workplace became Ukeles’s base of production, and she embedded herself in New York City’s Department of Sanitation, where she has remained as artist-in-residence since 1978.19

The versatile range of ambition and scale in Ukeles’s work has always reflected her belief that maintenance is an action that is intimate and formal, inconspicuous and observable, personalized and bureaucratic. For this exhibition, she took measures to engage the formidable architecture of the Queens Museum as a signifier for the magnitude of institutional and systematic maintenance. For example, the west façade of the museum was outfitted with 14 sets of salvaged blinking lights harvested from obsolete sanitation trucks. Thus the full girth of the building is transformed into the back end of a city utility vehicle. The artist’s sense of humor surfaces in other works too, including Social Mirror and Work Ballets (1983–2012). In the latter, heavy-duty trucks and barges enact enthralling rhythmical dances. Much of the playful absurdity in these works is the result of the artist’s use of incongruent scale and her inversion of the design and function of maintenance equipment. Setting this project apart from her maintenance practices, the ballets transform the tools of municipal upkeep into aestheticized cultural material that claims unesteemed public space as theater.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art, installation view, Queens Museum, September 18, 2016– February 19, 2017. © 2017 Queens Museum. All rights reserved. Photo: Hai Zhang.

Inside the main hall viewers are confronted with a wall graphic with gradations in color from lime green to cherry red. One Year’s Worktime II (1984/2016) organizes the abstract idea of a full year’s work through the grid deployment of clock faces printed over the color spectrum that represents the annual seasons. Ceremonial Arch IV (1988/1993/1994/2016) is also a memorial to work: used work gloves gleaned from city workforces jubilantly extend out of the top of an arching armature as if applauding, while collections of artifacts familiar to labor, such as gauges, truck handles, and mailbags, are grafted to the monument’s foundation. Peace Table (1997) foregrounds another type of work. A circular, transparent blue glass table is suspended under the skylights in the vast central hall of the museum. Sixteen wooden chairs host roundtable conversations with artists, city workers, and activists. The large-scale physical presence of these works stands in contrast to the intimacy of the exhibition’s countless documents displayed on gallery walls and in vitrines that record Ukeles’s 50-year career of examining and enacting service work and organized labor.

Not coincidentally, the Queens Museum exhibition comes at a point in time when the nature of work has radically shifted. New manufacturing and distribution technologies have yielded to the gig economy, so-called right-to-work laws, and the steep decline of unions. In addition, climate-change deniers are shaping state and national legislation while political leadership is reversing environmental protections. From this vantage point, Ukeles’s foregrounding of labor and the environment looks historic and lapsed, a progressive-era agenda that was forged by understanding the Earth as vulnerable and in need of compulsory maintenance and care. Perhaps today’s equivalent may be found in what is called the slow movement. “The slow movement is not a counter-cultural retreat from everyday life, not a return to the past, the good old days…neither is it a form of laziness, nor a slow-motion version of life… Rather it is…a process whereby everyday life—in all its pace and complexity, frisson, and routine—is approached with care and attention.”20

Understanding that all work has a local, regional, and global impact, Ukeles has dedicated a life’s work to platforming ordinary, ignoble, and invisible labor. She has influenced a generation of artists who have critically expanded her ideas, including Ben Kinmont, Andrea Fraser, Harrell Fletcher, and N.E. Thing Co. In my own work, I too am deeply indebted to Ukeles’s elevation of domestic routine and repetitive actions. Profoundly grasping that all work is greater than the individual who performs it, her entire practice is aimed at helping individual laborers understand and celebrate that too. An “artist, woman, wife, and mother,” Ukeles never loses sight of the Blue Marble inside of our mop buckets, garbage cans, and landfills.

Michelle Grabner is the Crown Family Professor of Painting and Drawing at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an X-TRA contributing editor. She lives in Milwaukee, WI.