Artist Lydia Ourahmane and curator Eliel Jones first worked together at Chisenhale Gallery, London, where Ourahmane staged her first institutional solo exhibition, The you in us, in 2018. They formed a close friendship and subsequently collaborated on other projects. In preparation for Ourahmane’s first institutional solo exhibition in the United States, at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts in San Francisco, the artist and curator began a conversation about their shared backgrounds growing up in Christian missionary families. In December 2019, during a few days of seclusion in the mountains of southern Spain, Ourahmane and Jones proposed to make part of their exchange public. Their conversation reflects on the ways that the artist’s work necessitates faith in art making as a tool and on the potential of belief as a driving force for change. They continued their discussion over email, and have edited the following collaboratively for length and clarity.

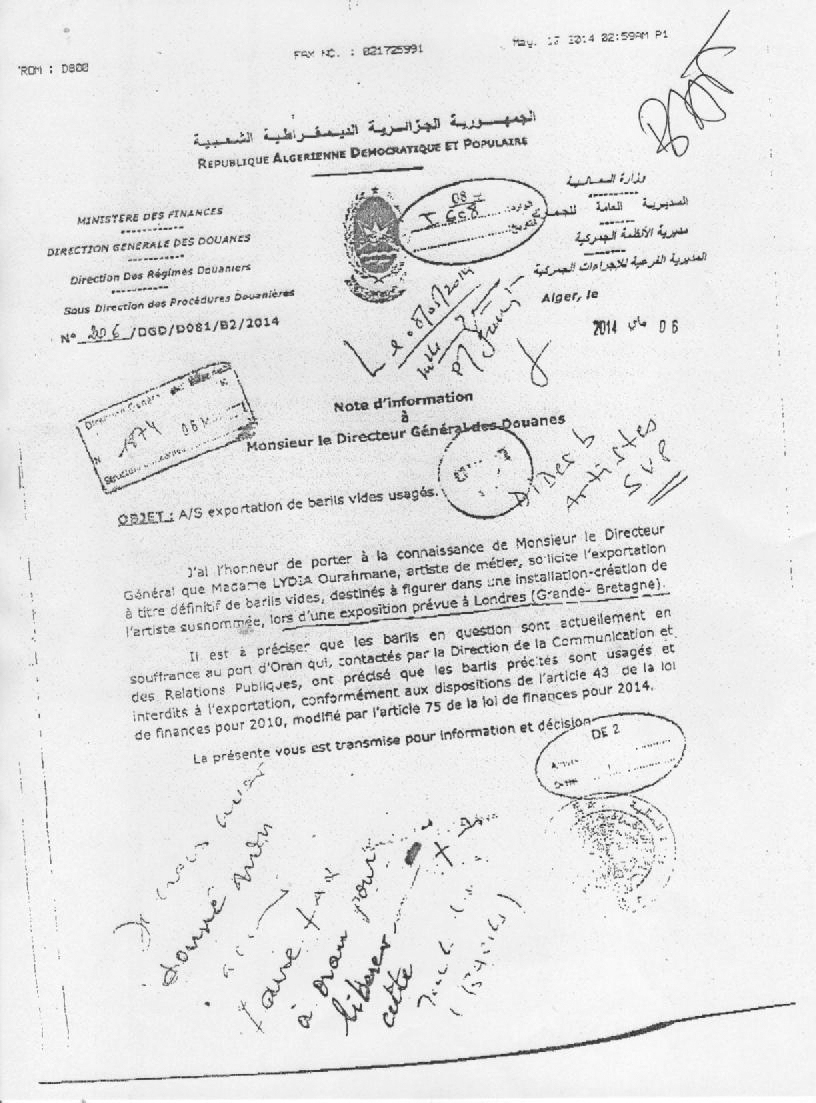

ELIEL JONES: I want to talk about our shared interest in faith and belief, and I’d like to start with one of the first public pieces of work that you produced, which was your graduate thesis at Goldsmiths in London. The Third Choir (2014) was a sound installation that consisted of twenty oil barrels assembled in a grid of five four-barrel lines. Each barrel contained a mobile phone tuned to an FM radio transmitter that functioned as a pirate radio station accessible within a two-kilometer radius. It seems to me that this work, and many that you have made since, very clearly exemplifies how belief—both as a process and a frame to describe or explain experience—is embedded in your practice. Here, it involved believing that you would be able to see through the complexities of making this work, even if it ended up requiring something as enormous as rewriting Algerian export law. It’s important to note that this wasn’t the original intention of the work but rather was the bureaucratic result of exporting the empty oil barrels from Algiers to London. You did, however, go into the project knowing that this particular movement of objects would likely be contested, and you purposefully sought to explore that process and document its unfolding. Though this task became incredibly arduous—at times seemingly impossible—you persevered. Considering the political tensions between the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region and Europe—based on a fraught history of the exploitation of natural resources that traverse borders that many bodies cannot—and how strange and potentially suspicious it would have seemed to government officials to define the empty barrels as “art,” this wasn’t short of a miracle.

Lydia Ourahmane, The Third Choir, 2014. Twenty oil barrels, radio transmitter, twenty Samsung E2121B mobile phones, sound, 9 27/32 × 13 1/8 ft. Courtesy of the artist.

LYDIA OURAHMANE: I struggle with the word miracle, but indeed it was. There are things that happened that I will never know how they happened, or that I cannot prove. Having said that, every communication—phone call, email, application, administrative paperwork, liaison contact, etc.—was meticulously logged and archived, making up The Third Choir Archives (2014–15), which consists of 934 documents. There was also human interaction that took place off-record, so to speak: handshakes, favors, the intercession of someone’s cousin . . . It’s surprising to consider empathy or humanity as being miraculous conditions in the airtight world of bureaucracy and administration. I continue to cling to these unspoken relational bonds as a means for resistance. Encountering someone in a position of power who actually wants to help signifies that there might still be some hope. That we are not entirely disabled, motorized, and operating at the disservice of each other. And we need to keep fighting for this kind of space.

JONES: How did you eventually get permission to export the empty oil barrels out of Algeria?

OURAHMANE: It was an unfolding of events. There were lots of problems from the beginning, but I took them—somewhat naively, somewhat hopefully—as being purely pragmatic, a matter of negotiation, of finding a way around and through the system. Sometimes that was just a matter of finding the next person I needed to speak to, or more likely, beg. The process of making this work—and so much of my work—is therefore necessarily relational. There were many moments of rejection, particularly when dealing with customs. The head of customs would straight up say, “No, this is impossible.” I took this to mean I had to leave and try again: revising my request and changing details of the application to go back and renegotiate the terms. I just couldn’t take “impossible” at face value. Legislation is permeable, especially when it is outdated. Laws are written and rewritten every day. This authority, therefore, is just an outline of reality, not an absolute truth. There are always holes, especially when there is room for interpretation. In this case, someone had to decide whether the objects I was trying to export were indeed classifiable under whichever category I claimed them to be in. The movement of the barrels was impossible under every category of existing exportation guidelines; being empty made them technically rubbish. Making visible the holes in legislation forces them to be revised.

After six attempts, as a “young girl” going to the same customs officers every day with a new proposal for the same objects, I started to get on their nerves. I was just twenty-one at the time, and a woman, so I wasn’t being taken seriously by the officials in these largely male-dominated contexts. One day the head of customs slammed his hands on the desk and told me: “Look, it is never going to happen.” I burst into tears. I regret giving him that. But I think this visible breakdown, the demonstration of my vulnerability in the context of that environment, was quite shocking and enough to move one of the officers to help me. This interestingly could be seen as patriarchal bargaining, by reverting to a stereotypically feminine response, which might have instigated an act of empathy on his part, outside the rule of law. He told me to try to contact the Ministry of Culture (after I confessed that what I was trying to export was for “art”). I left his office, went straight to an internet café nearby and wrote a desperate, Google-translated email to an address I had found under the Google search “Ministry of Culture Algeria.” That evening I received a phone call from the cabinet minister, and then it all snowballed from there. In the end, the result was the addition of a new section into the 2014 Finance Act to allow the barrels to pass. It was the first time an artwork was legally exported since 1962. At the time, every opening felt miraculous because there was always the risk of impossibility. The work was a rigorous endeavor in unmasking legislative issues that many artists had previously faced in the movement of artworks. Getting artworks out of the country often required smuggling. It is absurd that an artist should have to consider breaking the law when considering whether to show their work outside of the country. In many ways, this project forced me to think about the realms of possibility within art making, and how objects can become the matter through which change is instigated.

Lydia Ourahmane, The Third Choir (detail), 2014. Twenty oil barrels, radio transmitter, twenty Samsung E2121B mobile phones, sound, 9 27/32 × 13 1/8 ft. Courtesy of the artist.

JONES: I remember you telling me how the process of producing this artwork became also, unexpectedly, a way of connecting with your father, whom you involved in various translations of documents and conversations with local authorities. It’s perhaps fair to say that it would have required a great deal of belief in you for your father to get involved in that way. As an Arab Christian leader who has been at the forefront of fighting for the freedom of congregation and religion in a predominantly Muslim country, he’s not a man lacking in faith. Was he the best person to help you with what seemed like an impossible task?

OURAHMANE: He actually spent a long time trying to put me off. He was being very practical, proposing other “solutions” (including painting British oil barrels to look like the Algerian ones!). We had a huge fight over email, which was quite ridiculous in hindsight, but I was very passionate. My mum, on the other hand, was the one who understood it right away. She was praying so hard, honestly. She kept trying to get through to my dad, telling him that he needed to help me because it was part of God’s plan (!). He eventually recognized a common spirit in our passion, I think. My father would eventually act on my behalf in official contexts thereafter, he and a few close male family friends. This was really interesting to navigate, and I continued to work in this way across various projects, with my father, male family, and friends acting on my behalf. This delegation had its own agency as a proxy operation that had a different name/face/gender necessary for the work’s continuation. This was part of how I came to think around and beside bureaucratic systems, as hierarchies that can be negotiated by gesture, using the body as an interface, a carrier, simultaneously highlighting how some can navigate certain spaces (temporal, geographical, ideological) better, or at least more legitimately, than others. My father is very charming, he knows how to deal with people. He is also no stranger to conflict.

JONES: You’re also extremely charming, Lydia! I can’t think of anyone more charming than you. These personal traits and relational dynamics, as well as the strategies that you set in place to utilize them, are crucial. Because, as much as I’m keen on the idea of belief as a process (which includes your mother’s praying!), I’m also wary of placing it as the force behind the realization of this artwork, or even your practice at large. I think we need to probe a little deeper into what we mean when we talk about belief as an act that has a consequence or effect. Belief, in this sense, isn’t synonymous with an invocation of a supernatural force (i.e., God or some other spiritual entity) that will alter or bring about a course of events. Instead, one way I think belief enters your practice—and your life more broadly—is by allowing you to be in a state of suspension, often by giving yourself to situations that are very much out of your own control.

Lydia Ourahmane, The Third Choir (detail), 2014. Twenty oil barrels, radio transmitter, twenty Samsung E2121B mobile phones, sound, 9 27/32 × 13 1/8 ft. Courtesy of the artist.

OURAHMANE: I think suspension, or belief in that which is unknown is, to a certain extent, rooted in trust. But trust also requires confirmation. I remember that at the very beginning of The Third Choir, when all I had were these plans and research for the work, I came to the question of how I was going to fund it. I was a student at the time, and I had no money or savings. So I took out two loans from my bank. I remember meeting with my tutor, and she was very concerned about this, but I was adamant that it was the only way. I calculated that all in all it would cost around £7,000. A few days after meeting my tutor, I received an email from a representative at British Petroleum (BP), who said she had received my details from the artist Zineb Sedira, who recommended my work. They were looking for an Algerian artist to commission a painting to commemorate the forty-two BP representatives who were killed during a hostage attack on the In Amenas gas plant in the southern refineries in the Algerian Sahara the previous year. The painting would serve as a memorial, and it would hang in the BP offices in London. Receiving this email was surreal for many reasons. My research at the time was closely tied to the oil industry and the subdivisions of oil revenue in relation to foreign investments, of which BP was the epicenter. The oil industry, with its corruption and maldistribution of wealth, is often pinpointed as the root of the economic stagnation of Algeria, which is heavily reliant on its revenue from oil. (Oil amounts to 90% of its annual GDP.) When this hit Algeria’s economy the hardest, it was seen as a cause in the surge of those seeking to immigrate to Europe; many undertook extremely perilous journeys by sea to better their futures. The Third Choir was an interrogation into the objects’ ability to circumvent a system of movement by making the same physical journey that human beings were systematically denied.

A week after receiving that email, I had a meeting with a BP representative. We spoke at length about the events surrounding the attack, which happened during the inauguration of a new wing of the plant at In Amenas, and about the planned memorial. They said I was the first person on the list that they emailed, as I was “the youngest.” I explained that I was not a painter but that I would try some things out. I was given a color palette, some style references, etc. In the end, I was commissioned to produce this painting, which I completed and was coincidentally paid £7,000 for. I handed over the painting and flew to Algeria a few days later to begin working on The Third Choir. The series of events that facilitated the materialization of this work was surreal. The full circle created by the painting for BP inadvertently funding the work was a baffling twist of events.

JONES: These events are documented as part of The Third Choir Archives. Like other aspects of your work, they are laid bare for people to discover and unpack—morally and ethically—without clear direction or an explicit position being taken on your part. But isn’t the “miraculous” potentially entering some muddy waters here? Can you talk further about your decision to use BP money for the production of this work?

Lydia Ourahmane, The Third Choir Archives (detail), 2014–15. Nine hundred thirty-four documents: emails,

phone calls, proposals, authorizations, applications, customs clearance, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

OURAHMANE: As soon as the BP commission entered the orbit of The Third Choir, it became a fundamental part of the project, a sort of phantom limb. It is not about the painting, as such; it’s about leveraging it in the circulation of causal effect. This money is as much a material in the work as the barrels themselves, not only because it was a means for production but also because it embeds the project in the economic migration prevalent in the region. Especially with regards to the oil industry’s extraction of resources—which was built upon colonial contracts—the land itself remains exploited. The structural corruption and colonial debt coalesce in mass unemployment and economic stagnation.

When considering the polemics of funding and its potential for any form of remediation, I think it’s important to also point out that there are key differences between organizational and individual partisanship. It’s crucial to consider the agency of utility as a means for subversion, which became an aspect of this work. Yes, in this case, my identity—as an Algerian and a twenty-one-year-old art student at the time—was commodified for the purpose of the painting and what it represented for BP. But I don’t think that position detracts from the work, as I equally used them within a system of distribution that continues to enable violent activity. The very existence of BP was one of the questions The Third Choir dealt with. We must realize that, where there is very little room for negotiation, reversal in any capacity becomes urgent.

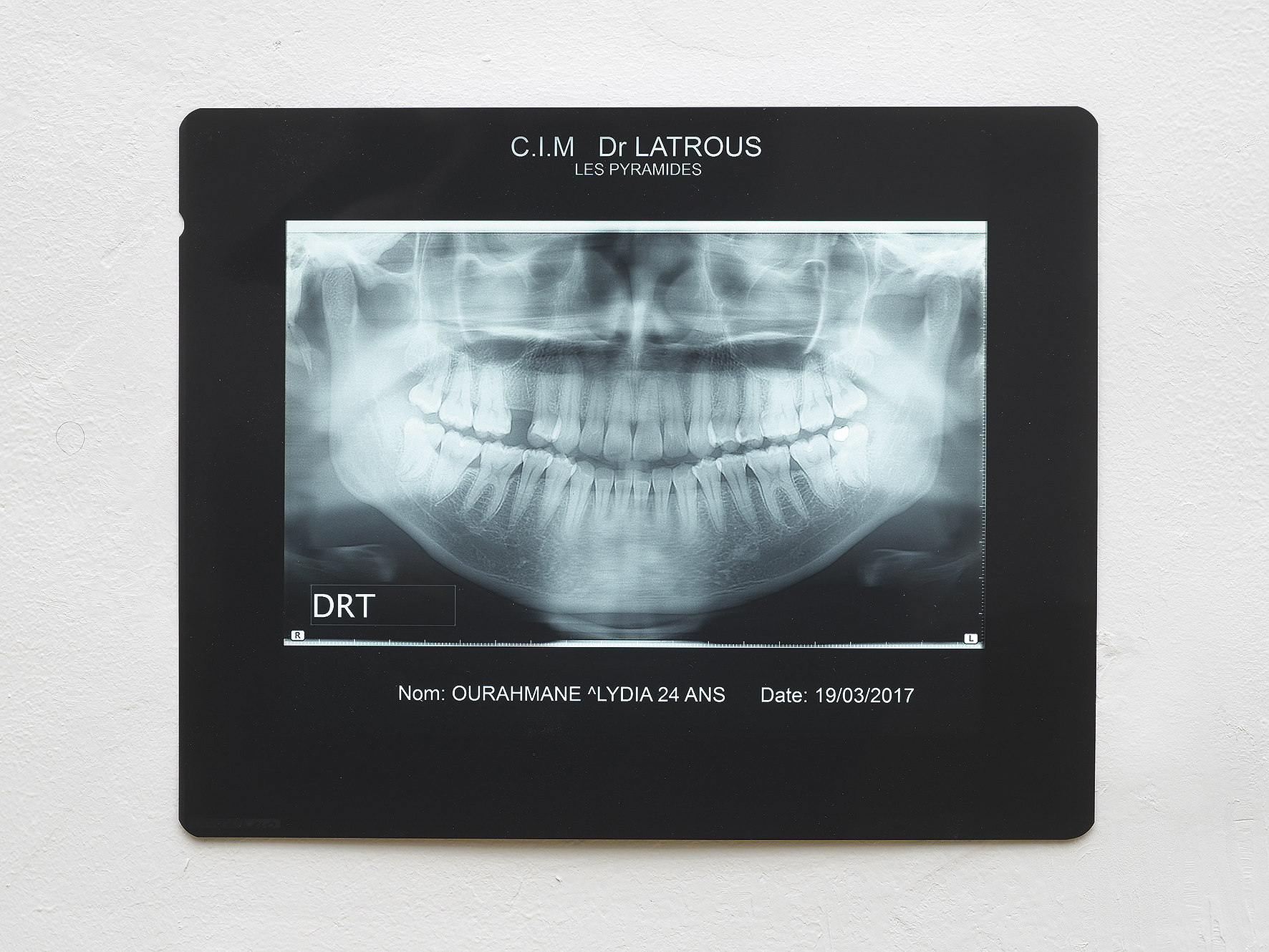

JONES: I think the process of locating the individual within the sea of the collective is very present in your practice. For instance, In the Absence of Our Mothers (2018) narrativizes singular histories pertaining to your grandfather’s and a stranger’s strategies of escape (from war and an economically stagnant country, respectively) to draw attention to the extremes that people put themselves through in order to survive. Importantly, it also comes back to you, and your own body. For this work, you permanently inserted a gold tooth into your mouth, in reference to your grandfather’s removal of all of his teeth in order to be discharged from the army. You made the tooth with a gold chain that you bought from a young stranger in a clandestine market for the price of a ticket to be smuggled on a boat bound for Europe. I think it’s significant that you always return to the experience of a body—a particular body—in the world in order to highlight a structural lack. Though these stories are about these individuals and their lives (and partly about your own experience and personal history), the overarching narrative of the work is about the human condition of survival.

Lydia Ourahmane, In the Absence of Our Mothers (detail), 2018. X-Ray, text, two 4.5g 18kt gold teeth (one of which is permanently installed in Lydia Ourahmane’s mouth), dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Chisenhale Gallery, London.

OURAHMANE: I have always been very aware that I have a position to take in the world. I think it is part of having had to adapt to various situations in my life that maybe I had little or no control over. The experience of displacement is inherently political, be it of a body, a material, or a location. What does it mean to depend on distance? How does distance politicize the realm of experience? Yes, there is always something that gets lost within the act of translation, but this distance is also material. When something or someone is “out of place,” they attain a hypervisibility; this can simultaneously allow for transformation, because it interrogates those who recognize that difference as such. Just as a body in a space takes on the form of resistance. Being racialized and gendered is a constant negotiation that plays out in relational dynamics, and it is often preceded by the question: where are you from? This tool for classification tries to create some order/understanding about how a seemingly unrecognizable being has entered any space that is secured under paradigmatic racial, ethnic, social, and gendered markers. The problem is that this exercise ultimately also always predetermines who is familiar or strange, inside or outside, legitimate or not.

In the Absence of Our Mothers explores this distance through the transformation of a gold chain into two gold teeth, one of which is permanently implanted in my jaw and the other of which is exhibited alongside an X-ray and text. Initially, it was a piece of jewelry supposedly belonging to the mother of a young man I met in an open market; I bought it for the same price as a seat in a clandestine boat to Europe. The chain remained in its original form, surfacing once on the hand of a volunteer during the opening of an exhibition that I participated in. Three years later, I came into contact with my uncle, who retold the story of my grandfather to me. He was a very active member of the National Liberation Front (FLN) and the fight for Algeria’s independence from France. Before his militant life, my grandfather was conscripted into the French Army, initially serving a compulsory military service and going on to be held for thirteen years against his will. The story goes that he was an excellent sniper, so they used him to train other soldiers. He was then asked to go and fight in the French Army against Germany in World War II. He knew that if he went, he probably wouldn’t survive. Rather than sacrificing his life for his other enemy, France, he pulled out all of his teeth, rendering himself disabled and therefore unfit to fight in the army. He was subsequently discharged.

In the Absence of Our Mothers was not purely to do with distance in terms of the movement of a material from A to B. Rather, I was thinking about spanning the distance of history, the present moment, and dreams in the future tense. It is also about how narratives can be bridged by their introduction to one another through a material affect. In this way, I imagine that the work began in 1944, when my grandfather removed his teeth, and it ended in 2018, with the implantation of a gold tooth in my mouth. This transformation is carried through the displacement of objects or materials from their intended use, where they can negate their system of meaning by forming a symbiosis. Time, therefore, fundamentally allowed this relational bond to be held together by a common struggle, recurring in a different form.

Lydia Ourahmane, In the Absence of Our Mothers (detail), 2018. X-Ray, text, two 4.5g 18kt gold teeth (one of which is permanently installed in Lydia Ourahmane’s mouth), dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Chisenhale Gallery, London.

JONES: At Chisenhale Gallery, this work was accompanied by Paradis (2018), a sound installation that reverberated from under a raised floor and onto the soles of the visitors’ feet across the entire gallery. At the time, you were thinking through sound in this exhibition as a way of passing something on to the audience’s own bodies. How does belief enter this process of artistic production?

OURAHMANE: What I admire about belief in the religious sense is the collective space that is offered to the practice of longing (through prayer, for instance or being in constant seeking) with the understanding that it’s supposed to do something. At the end of the day, it has a lot to do with intentionality as well as conviction. And I do think about making exhibitions in this way. The work manages to become the mode of transmission between an experience and its collective mattering, and though art appears to be more tangible, it still definitely also requires belief. My spiritual life is rooted in an ability to discern and navigate situations through intuition. I say it is spiritual because it is a personal quality as much as it’s something that I have to practice and build. Listening is subsequently how I approach the materials and narratives I work with, and sound, therefore, is a recurring tool. Oftentimes, when I am deep in a process, all I wish is for people to be as close as possible. Sound is the attempt to collapse this distance, it is the immaterial and invisible component that often becomes a surrogate for the absence of a body/experience. It offers itself as a tool for experiential knowledge.

Lydia Ourahmane, pH 8.7, 2015–16. 356kg of fertile soil smuggled from Medea, Algeria, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

JONES: You do extend an invitation within your work—perhaps almost as a requirement, or at least a provocation—that the viewer should come open to the act of believing and/or having faith in order to fully experience it. To clarify, I’m not talking purely on religious or spiritual grounds here, though we could be. In part, I mean that your works often ask for a belief in the narratives embedded in their making, be it the moving of oil barrels across the sea (The Third Choir), the smuggling of 356kg of soil from Medea to Switzerland (pH 8.7, 2015–16), or the melting of a gold chain into a gold tooth that gets permanently installed in your mouth (In the Absence of Our Mothers). However, you don’t ask us to go in blind. You provide evidence of such movements and actions, but the request or invitation for belief within your work perhaps more importantly also materializes as an experience: come and listen to these barrels reverberate, walk across this stolen soil, imagine the pain in my (and my grandfather’s) gums. You are implicating us throughout these works while also prompting us to think why they literally—and emotionally—matter.

This condition of belief was perhaps the most central question of your exhibition صرخة شمسية Solar Cry, at CCA Wattis, in February 2020. Here, through a series of sonic and environmental changes to the space, you sought to make manifest the ways in which belief can be physically present or, as you say, “registered on bodies.” To a great extent, the work explored this question through acts of material and immaterial suspension: of a human voice, of the light entering the room, and even the visitor’s walk across an expanse of seemingly empty—but in many ways incredibly full—space.

صرخة شمسية Solar Cry, installation view, CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, February 6–March 28, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Impart Photography.

OURAHMANE: The works that I produced for the CCA Wattis show functioned as a collective voice: an opera singer separate between two notes, the silence of an inhospitable expanse reverberating through the architecture of the building, and crystallized salt crushed underfoot by its meeting with the bodies of visitors. I was thinking about this multiplicity and cacophony of voices as a suspension. “Belief” and the experience of the sacred are always in motion and therefore impossible to be fully articulated. In that sense, the show was also about this impossibility, where sound mediated the disparate sites the exhibition sought to navigate: an operatic piece recorded on site, a walk through the expanse of the Sahara Desert, and my mother’s memoir, “Divine Encounters 1974–1992.” Each location had a common spirit in “longing,” which one can only attempt to translate as a feeling.

JONES: I’ve always been touched by the idea of materializing feelings. Yvonne Rainer’s “feelings are facts”—the title of her autobiography and, apparently, a dictum made by her psychotherapist—is synonymous for me with “feelings are matter.” I see this as much in the sense that feelings are important as that they are, themselves, physical and haptic forces. Rainer’s “longstanding mania for ‘telling,’” which she confesses in her book, is to me akin to the way you insert biography and personal history into often immaterial artistic forms—choreography and sound—that also manage to extend beyond your own body. In this sense, feelings are laid bare not only so that they can be borne witness to, but also so that they can be expressed and transcribed from body to body. Can you go a little bit into how you sought to materialize “feeling” in this exhibition?

OURAHMANE: The work صرخة شمسية Solar Cry (2020) was a recording of silence embedded in a wall. It barely registered, until you went up to the wall and pressed your body against it. I recorded the piece during a 200km walk in Tassili N’Ajjer, a desert expanse between Algeria and Libya. Here is a key example of the question of trust that we’ve been referring to: I had to place my trust in the person who was to guide me through an inhospitable expanse of land that I could not navigate in and out of alone, for it would have been impossible to do so with my own body and mind’s ability to cope, perform, know that space, and survive. This is also a good example of the space of suspension that we spoke of earlier: a gesture of willingly entering a space within which you are at the mercy of something or someone else.

A♭, B♭ (2020) was the first time I worked specifically with the human voice. I asked an opera singer to sing an A flat continuously for one hour and a B flat continuously for one hour, recorded consecutively. As a listener, you enter this passage of time by recognizing her voice becoming tired, trying to hold itself; the straining becomes familiar. At the time, I was reading Audre Lorde’s essay “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” and I gave it to Nikola (the opera singer) a couple of days before the recording. Lorde speaks about the danger of misunderstanding as a risk in the act of communication but that it is simultaneously imperative in the service of truth. The danger of vulnerability is incomparable to the burden of silence. This is something that I have been thinking a lot about since.

X—

Eliel Jones is a writer, curator and organizer based in London. He has curated projects in the United Kingdom and internationally, including in Jordan, Poland, and the United States. He has written essays for various artists’ catalogs and publications, as well as reviews and features on contemporary art and performance for Artforum, Frieze, The Guardian, Flash Art, Mousse, Spike Art Quarterly, and MAP Magazine. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he delivered monthly commissioned projects across the world through Queer Correspondence, a mail-art initiative.

Lydia Ourahmane is a multi-disciplinary artist living and working between Europe and North Africa. She graduated from Goldsmiths, University of London, in 2014 and has exhibited internationally. Recent exhibitions include Risquons-Tout, Wiels, Brussels; صرخة شمسية Solar Cry, CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco; Homeless Souls, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark; Manifesta 12, Palermo; Jaou, Tunis; Droit du sang, Kunstverein München, Munich; 2018 New Museum Triennial: Songs for Sabotage, New Museum, New York; and The you in us, Chisenhale Gallery, London. She presented her first solo exhibition in Switzerland at Kunsthalle Basel in January 2021 and is included in the 34th Bienal de São Paulo.