Untitled, n.d. © Gregory Colbert.

#1 Ashes and Snow and the Nomadic Museum

Ashes and Snow is the 8th wonder of the world. —KPFK Radio1

For those who failed to catch this wonder that has already graced both coasts (Pier 54 on the Hudson from March–June 2005 and Santa Monica from January–May 2006), Ashes and Snow is an exhibition of the work of one artist, the relatively unknown Canadian photographer Gregory Colbert (no known relation to Steven Colbert of The Colbert Report). Presented in a huge, 56,000-square-foot structure, which is a collaboration of sorts between the artist and renowned architect Shigero Ban, the show was funded by the chairman of Rolex, who bought the exhibition in its entirety after its first showing at the Venice Arsenale.2 The structure, called the “Nomadic Museum,” was specifically designed to house the traveling exhibition, and is constructed of 148 stacked shipping containers that can be easily broken down and re-installed in new locations. Like the glowing white Cirque du Soleil tents that graced the same spot in Santa Monica beside the pier, the Nomadic Museum is a spectacle in itself, brightly lit at night and looming over the tourist-inhabited pier by day. Undeniably, the building is rather genius—playfully stacked containers are webbed with tent material to create a cavernous, re-usable space out of recycled materials.

But once inside there is little sign of the tight logic governing the outside structure. After waiting on the ubiquitous 30-minute line and paying the $15 admission, one enters a space not unlike Cirque du Soleil’s Canadian circus; there is new age music playing, it is dark, and there are animals everywhere. Colbert is apparently fixated on a fictitious utopia, some time in the past, when people and animals lived together as one. As the viewer follows the prescribed trail—a wooden boardwalk over rounded river stones—one passes floating images of elephants and cheetahs being caressed by young children and women with their eyes closed. There is a 90-minute film narrated by Lawrence Fishburne and two shorter “film haikus,” all featuring more exotic children, exotic women and exotic animals walking, floating, or swimming together in exotic places. Occasionally the artist, a tall pony-tailed man, makes an appearance. According to the exhibition material, some of the animals are “wild” and some are “habituated to human contact” but each vignette presents only perfect images of animals and humans with their eyes closed, silently inhabiting the same space. We are also left a bit in the dark about the way that the images are created. The exhibition material tells us, “These mixed media photographic works marry umber and sepia tones in a distinctive encaustic process on handmade Japanese paper. The artworks, each approximately five feet by eight feet, are mounted without explanatory text so as to encourage an open-ended interaction with the images.”3 At the end of the trail there is a bookstore, where visitors can purchase, for $20,000, the Codex of the exhibition (printed on rice paper and bound with 300-year-old book covers). There are also more modest books of animal photographs for something like $30, CDs of the musical score, t-shirts, notepads, postcards, etc.

Perhaps some readers will find it strange that an artist without any gallery representation is able to launch a world-wide exhibition of his own work housed in a dedicated museum designed by an all-star architect, and charge a $15 admission fee. It is strange. And from within the contemporary art world, it could be seen as scary. As an art exhibition staged in something called a “museum” by an artist, it appears to threaten the institution of contemporary art, which is so carefully perched upon a web of art circulated through and by major museums, collectors, dealers, art schools, and publications. The sponsoring philanthropic group, The Rolex Institute, might lend the appearance of some kind of institutional seal of approval, but that is quickly overshadowed by the fact that the chairman of Rolex owns the work in the exhibition and funded many of Colbert’s safaris over the past 13 years.

When standing in front of Ashes and Snow, I felt as if I had no way to comprehend what I was looking at. It’s an exhibition of fine art by an artist, so it can’t simply be filed into the science/spectacle category with such blockbuster exhibitions as Body Worlds. But it also can’t simply be pushed down into a “bad art” category due to its contrived nature, because it is not exactly art. It is largely composed of something other than art—this theatrical and monumental quality. And then, the overwhelmingly positive public response to this “art exhibition” needs to be acknowledged. What are the consequences of the success of this venture, both good and bad? What does it mean for the already precarious future of contemporary art in the eyes of a larger general public? And how are the “real” museums challenged? Perhaps Colbert (with his Rolex money) is more entrepreneur than photographer, putting together the kind of traveling show that we associate more with the turn of the last century than with our own.

Untitled, n.d. © Gregory Colbert. (The image shows Colbert swimming with whales.)

#2 Exhibitions of Industry and Art

The magic columns of these palaces Show to the amateur on all sides, In the objects their porticos display, That industry is the rival of the arts.4

It seems that the beginning of the estranged relationship between exhibition and display starts with the industrial exhibitions and World’s Fairs of the nineteenth century. Benjamin’s Arcades Project contains a chapter on “Exhibitions, Advertising, Grandville” and opens with the quote above, but notes about the large-scale industrial exhibitions are present in nearly every chapter, and repeatedly, the notes about the exhibitions seem to pose questions about the affects of awe on art. These concerns are taken up with more specificity in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Reproduction,” but the looseness of the Arcades Project better highlights the pure wonder and exhilaration of these moments.5

These enormous and mind-blowing exhibitions were the size of the villages being left behind as people migrated in droves to the new urban cities of Europe and America. And that moment, where the marvel of industry surpassed that of the artist, marks the modern break where the fine arts had to define themselves as something more, and other, than that which causes awe. It is here of course that we get critical art, we get Baudelaire, we get Zola, we get the Impressionists digesting the anxiety of living in modern times—we get content that goes deeper than the pinnacle of craft, or the showcasing of handiwork.

#3 The All Russian Exhibition Center

I recently spent a week in Moscow, and had the perplexing pleasure of visiting the All Russian Exhibition Center. It had been down-played in my guidebooks, but this enormous park of sorts, covering nearly one square mile to the north of downtown Moscow, encapsulated my visit to the city. The All Russian Exhibition Center (like Moscow itself) has a convoluted and politically-driven history, marked by numerous radical changes in mission, and a spatial mapping system that I could not decipher, with a lot of enormous buildings and a generous sprinkling of ornate architectural elements that are unexpectedly foreign and sparkly. The park contained grand buildings of vastly different styles, each dedicated to a former state of the Soviet Union or an area of industry and filled with a seemingly random arrangement of displays, including Pez dispensers, Smurfs, textiles of Azerbaijan, wooly mammoths and space rockets. I spent at least half an hour taking pictures of the main fountains—the “Friendship of Peoples” and the “Stone Flower”—as they are undoubtedly the largest, most ornate fountains known to man.

This place, constructed in order to showcase the grand accomplishments of the Soviet Union and all of its regions has now been reconfigured as a publicly owned company functioning as a kitsch museum, outdoor park, electronics flea market and overgrown convention center. (The website calls this “its architectural, leisure and exhibition ensemble.”)6 Like Los Angeles, it is rare to catch glimpses of a public in Moscow, outside of Red Square and surrounds. And it is especially rare to see them smiling. So it was surprising to find that this former showcase of Soviet Industry is still the place where Muscovites gather, where they eat ice cream, drink beer, and roller blade—where they seem most comfortable.

This building, which according to the All-Russian Exhibition Center English-language map is called “Central,” housed the Pez Dispenser and Snoopy Figurine collections, among other things. There is a large statue of Lenin in front, 2006.

The Friendship of Peoples Fountain, All Russian Exhibition Center, Moscow, 2006.

The Friendship of Peoples Fountain, All Russian Exhibition Center, Moscow, 2006.

#4 Awe in contemporary Art

What marked the viewing experiences of the Nomadic Museum and the All Russian Exhibition Center for me was my inability to understand the logic or progression of decisions that would result in such exhibitions. Perhaps that is awe. I can see a bit of the spectacle that taints the Van Gogh or Monet or Motorcycle exhibitions that travel the world at our most esteemed cultural institutions. Contemporary art-snobs can understand how those exhibitions fund the edgier programming or welcome the public back into the museums where they might stumble upon something other than the blockbuster they paid to see. But in these two exhibitions in Santa Monica and Moscow, there was something else, some other boundary crossed—a territory I could not have anticipated, where reality exceeded my imagination. Part of this excess is linked to the illogical, unfathomable or audacious histories of these sites, but the large appreciative swarms cueing up indicate that there is a public, a large one, that finds something compelling, some need met. Perhaps it is the return to the display of the rivalry between industry and the arts?

As either verb or noun, “display” is not an art-world term, “display” is for trade shows, for libraries, for craftier arts. Contemporary artists “install” and “exhibit” work. We show it. It is the viewer who is responsible for finding it, understanding it, reading it. Things that are displayed are put out in an ostentatious manner so as to explain or declare themselves to the viewer. Things that are displayed are not discovered: displays do not want to be questioned.

Matthew Barney, Shirin Neshat, Andreas Gursky, and Anish Kapoor are some of the artists who have recently played the awe-card. They have exhibited work that exceeds the boundaries of what we think possible, created objects or films that seem to overwhelm our ability to logically process how the work was constructed or undertaken. And the outcome is what? They exceed the boundaries of art and become displays—displays of the techniques of art taken to the extremes of human ability. And that might not be art. In other words, awe is too big for art. It is necessarily tied to a display of great power that overpowers the individual (think “shock and awe”), closing out space for reflection—for discovery, understanding and reading.

And if Gregory Colbert is right in saying that “People need to restore their sense of awe,”7 I have to ask, once we get it back, what are we to do with it?

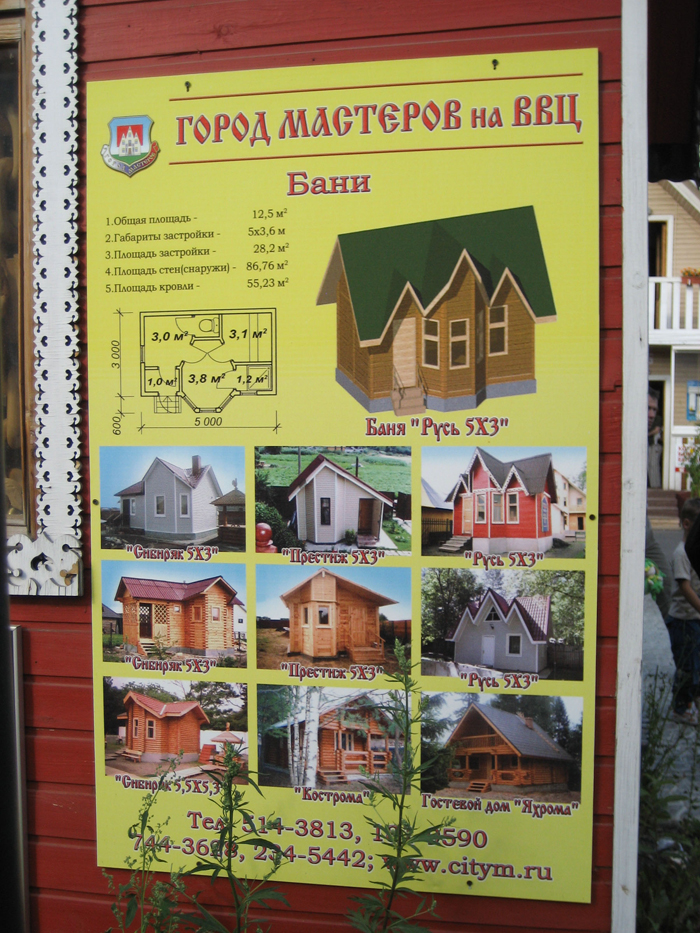

Poster advertisement at the pre-fab homes display at the All Russian Exhibition Center, Moscow, 2006.

#5 Back to the USSR

The display I was most drawn to at the All Russian Exhibition Center was a cluster of pre-fab houses nestled in between two buildings that the map declares to be Culture and Optics. Unlike the modern, streamlined, pre-fab homes we are accustomed to seeing in Dwell, these homes looked like they had been based on Little Red Riding Hood’s Grandma’s house. On approach, it was impossible to tell when they had been constructed, if this was a new display or an old one, if these houses were still desirable or relics of the ‘50s, or the ‘30s or the ‘80s. After entering the little village, complete with active playground and hot dog stand, there were signs and posters indicating that these houses were indeed available for sale, and the people wandering around seemed to have the air of potential home-buyers. But the status of this display became even less clear after I actually went inside. I decided to try to find a bathroom. I walked to the largest house, which seemed to hold the office, and immediately in front of me was a door marked “WC.” Inside the room, which was under the stairs, I first noticed an awful smell, a puddle-filled plastic covered floor, and a large hole in the wall partially covered with aging duct tape. I then noticed that the toilet and sink were not very confident in their connection to the walls. I hurried back outside, confused.

Shana Lutker is an artist living in Los Angeles.